Adam West assists the author during part of the shooting phase of the testing. Due to the heavy repetition of firing over 100 rounds of 12 gauge slugs in this single shot platform, shooters took turns in this position.

By Jeff W. Zimba

What happens when you mix a few individuals with a passion for firearms research with a Chronograph, a Chop Saw, a Shotgun and a Title II Manufacturers License?

The Great Shotgun Chop of 2007.

Along with the increase in mass production of short-barreled rifles and short-barreled shotguns on the market today, there have been several debates about the effect of these short barrels on actual performance. Since the ability to measure the speed of a projectile was perfected, there have been countless muzzle velocity tests on numerous firearms with an enormous number of loads. Most tests come to a similar conclusion; that a shorter barrel equals a lower projectile speed, therefore making the firearm less effective at longer ranges. Published data for long barrels and short barrels has been available in the past, but something always seems to be missing. How about all those lengths between very long and extremely short? What about continuity with loads, weather and firearm type? All of those factors will affect the final results. What if you could measure the same firearm with the same ammo using the same barrel and collect all required data on the same day? Well, that is exactly what a small team from Small Arms Research in Fairfield, Maine prepared to do.

The concept of this test was mentioned on the popular Class III firearms discussion website www.Subguns.com and within what seemed like only minutes, a fellow Brother-In-Arms with an interest in the test results offered to donate a test firearm and promptly shipped us a 12 gauge, 30-inch barreled, H&R single shot shotgun. A few hundred 1-ounce slugs were purchased, and an uninterrupted day at the range was scheduled.

Unloading everything in preparation for our testing looked more like a construction project than a simple gun test. A generator, a chop saw, and a 1/2-inch drill were set up along with the chronograph, several targets and lots of 12-gauge ammo. Our test firearm needed a little minor surgery as the stock was weathered and cracked and for safety purposes we reinforced it a little before the shooting began. We took a few crucial measurements and started the testing.

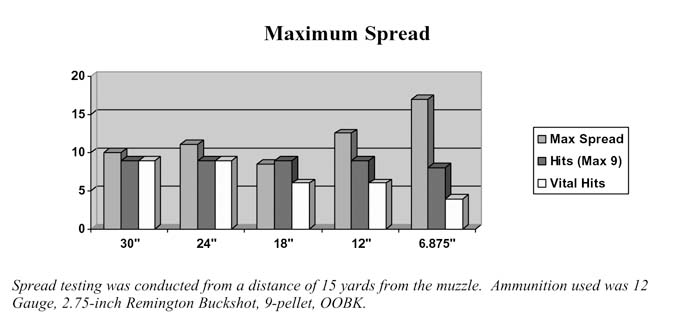

Since we would be measuring muzzle velocity with several different barrel lengths we decided to gather a little more data at the same time and also measure the effect the barrel lengths had on shot spread. We selected a standard 9-pellet 00-Buck because of its popularity and effectiveness in many circumstances.

Commence Fire!

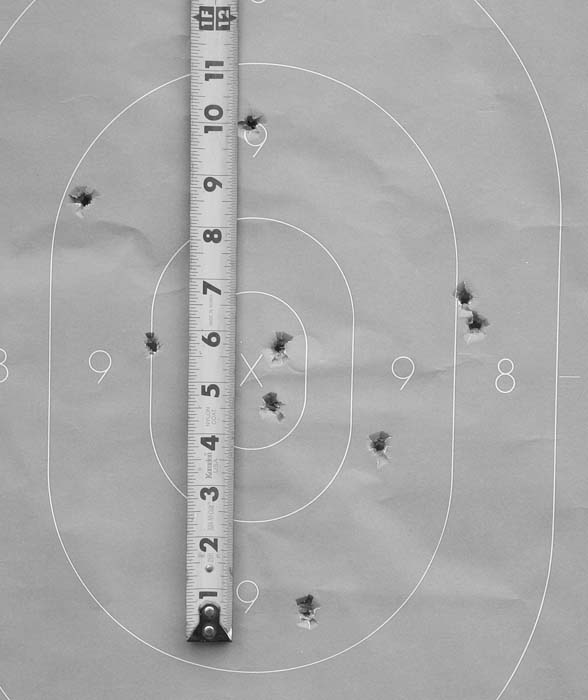

After everything was set up and in place, and the barrel was measured and marked in 1-inch increments, it was time to get shooting. We had a lot of ammo to shoot and lots of data to gather in one short day. With a barrel length of 30 inches and an inside diameter of .695 we started by firing the 00-Buck at a distance 15 yards. Although we were measuring the muzzle velocity with the slugs at 1-inch intervals, we decided to measure the spread of the buckshot every 6 inches in barrel reduction. Initial shots were fired, spreads were measured and it was time to start with the slugs. At every length, 3 rounds were fired to provide an average. This would alleviate the chances of encountering an odd round that would affect the test results. On the rare occasion where one of these questionable rounds was encountered, a 4th round would be fired to use in the equation and the odd round was discounted.

All muzzle velocity figures were measured using a PACT MKIV XP Chronograph and Timer from a distance of 8-feetfrom the muzzle. As we watched the flex of the screens with each round fired, it quickly became obvious that this day would be a serious endurance test of the Chronograph at the same time. We are happy to report that it survived just fine and is still used regularly.

The first readings with the 2.75-inch Remington Slugger, 1-ounce rifled slugs in the stock shotgun averaged 1,555 feet per second (fps). The generator was fired up and it was time to start chopping. The barrel was carefully squared off and the abrasive wheel easily sliced through the barrel. The barrel was de-burred after each cut and the inside diameter was measured every time. Much to our surprise, the inside diameter of the barrel was completely consistent throughout the entire test.

A Brief Side Experiment

The shotgun barrel was marked only “choke,” and the initial bore measurement we took was .695. After the first chop, and all the way to the last, the inside diameter remained exactly .725. The only time there was a fluctuation in the inside diameter of the barrel was when we tried a little experiment and created a “deformity” intentionally. At one point in between the regular cuts, we used a pipe cutter to shorten the barrel to see if our displacing some of the material (as opposed to the clean cut using the chop saw) could create a field improvised “choke” and have an effect on the pattern while testing the buckshot. After the normal de-burr process we checked the pattern against the previous, and found that the slightly tighter (.710) muzzle actually created a horizontal pattern similar to that created with the Duckbill muzzle device tested in an earlier issue of Small Arms Review. The pattern had exactly the same dimensions as the previous shot, but it was wide instead of tall. While the first pattern with the clean cut barrel measured 9 inches wide and 11 inches tall, the one with the reduced muzzle created a pattern 11 inches wide and 9 inches tall. This was the only time we deviated from the parameters we set for the rest of the testing, and after this short curiosity was explored we immediately resumed as planned.

Back on Track

As you will see in the included Muzzle Velocity chart, as the barrel got shorter, the velocity typically dropped slightly or if there was an increase, remained very close to the previous shot. The changes were fairly consistent and mostly minimal, until we reached the 20-inch mark. In the 10 inches of measurements recorded from 30 inches to 21 inches, the muzzle velocity never varied anymore than 150 fps. At the point when we dropped in length from 21 inches down to 20 inches the velocity dropped an immediate 250 fps. Noticing this drastic change, we fired several additional rounds to make sure there was not some kind of ammo abnormality but all remained in the same area. At this point we thought we discovered some magic combination of barrel length where there is a drastic change downward, and just as soon as we digested the previous numbers, we were scratching our heads on the very next cut. As soon as we dropped down to 19 inches in length, the muzzle velocity shot back up almost 220 fps and from that point on continued on the previous, gradual decline, as the barrel got shorter. We have absolutely no explanation for this 20-inch abnormality and would certainly entertain any ideas to help understand it.

Other than the previously mentioned 20- inch abnormality, the testing produced results that we expected to see. The point where there was a sharp drop in muzzle velocity was the place we were looking to pinpoint and on average the difference from the 30-inch barrel all the way down to 12 inches only gradually declined approximately 200 fps. In our opinion, that is quite consistent for such a drastic difference in length. It was below 12 inches however, that the velocity started to drop quickly. With a drop of only 200 fps in the first 18 inches of barrel reduction, the next 6 inches produced a smooth and consistent drop falling 250 fps when decreased from 12 inches in length to 6.875 inches in length. If there is indeed a magic number for barrel length where muzzle velocity rapidly declines, that number would seem to hover around 12 inches in length.

The final muzzle numbers for the tests conducted during The Great Shotgun Chop are included in the accompanying chart but the summary is as follows: the starting muzzle velocity with a 30-inch barrel was 1,555 fps. The highest muzzle velocity measured was at the 26-inch point at 1,605 fps. The shortest barrel length tested was 6.875 inches and the muzzle velocity at that point was 1,117 fps. The spread from fastest to slowest recorded average was 488 fps. As indicated in the included data there is no consistently reliable formula to determine decrease or increase in muzzle velocity based on initial barrel length vs. inches cut. This is mentioned because the most popular question asked during the research phase of the testing was, “What was the drop in muzzle velocity per inch cut?” From 12 inches down to 6.875 inches it could be established that the average drop in muzzle velocity per inch of barrel reduction was 48.2 fps, but it would not be reliable as the sharpest decline was in the last few cuts.

Spread ‘Em

Thus far, the focal point of this article has been based on the muzzle velocity portion of our tests. For those interested in the “scattergun” function of their shotguns, this section should be of particular interest. All the test firing was done from a distance of 15 yards from the muzzle. Targets used for the testing were “Economy B-27 Silhouette” targets (used because “hits” are much more visible and easier to photograph on the green targetthan the traditional black targets) and the point of aim was center of mass, or at least the best possible with no bead or other aiming implement.

There is a separate chart showing the data from this portion of the testing but the summary is as follows. There were 5 barrel lengths tested. Starting at 30 inches the spread was measured at every 6 inches in barrel reduction. Ammo used was RemingtonBuckshot, 9-pellet, 00-Buck. The maximum number of hits was 9, and hits were measured for extreme spread distance. They were also rated as grazing hits, vital hits or misses, based on their position on the target. At a barrel length of 30 inches the maximum spread averaged 10 inches. All pellets were scored as hits, and all were vital hits. The other end of the spectrum was a barrel length of 6.875 inches where the average spread was 17 inches. The number of hits recorded was 8 and the number of vital hits was only 4.

Not every “rule of thumb” came into play in this portion of the testing any more than it did in the muzzle velocity testing. Just like some barrel lengths seemed to “like” the slugs more than others andconsistently record a better performance, the same was true with the Buckshot. While the fact remained consistent that the shorter the barrel would become, the lower number of hits, including vital hits would also follow suit, The “Magic Number” with the buckshot, at least as far as spread size, was recorded with an 18-inch barrel. At its smallest size, the pattern averaged only 8.5 inches. The next test however, at 12 inches in length, would find the spread growing again and would continue to do so until the end.

Conclusions

This series of tests proved to be extremely interesting and the results quite different from “the rule of thumb” that the author has heard repeatedly over the years.Although looking only at the small picture by comparing the first round and length tothe last round and length, the outcome would be exactly as expected: “Shorter barrel equals slower round and bigger group.” It is the subtle details in between the extreme ends of the testing that provide the real data and made the results much more interesting than we initially thought possible. Aside from the unexpected results in the 20-inch muzzle velocity testing, it is a safe assumption that for maximum performance at a minimal size for shooting slugs, a 12-inch barrel seems to be the optimum length. In thebuckshot testing, it was the 18-inch stage that performed the best and had the smallest extreme spread. The spread of the 12- inch barreled version was almost identical to the much more cumbersome 24-inch barrel, with an extreme spread only 1.5 inches greater. After conducting these tests it is our opinion that a 12-inch barreled shotgun with proper sights gives the owner/ operator the best performance in the smallest practical package without any major sacrifices in size or performance.

By taking a deep look inside something considered to be obvious, at least on the outside, we were able to harvest some valuable data on an age old topic. With all the recent chatter about the effectiveness of short-barreled rifles, maybe next time the test subject will be a centerfire rifle. I can think of several HK clones and variants, not to mention many models of the Black Rifle that all employ extremely short barrels. Add to those the ever-growing popularity of the “Krink” AK-type guns and we seem to have a full field of potential candidates.

Legal Notes

Please bear in mind that in order for a traditional Title I shotgun to remain legal under Federal Law without further registration, it must have a barrel of at least 18 inches in length and a minimum overall length of 26 inches. The author of this article is a licensed Title II Manufacturer and the test subject was registered as a Short Barreled Shotgun for the purposes of completing this research. As an individual you can do the same thing as we did as long as you receive prior approval from BATFE in the form of an approved ATF Form 1 “Application to Manufacture an NFA Firearm” and pay a $200 manufacturing fee. If you wish to purchase a short-barreled shotgun the same $200 fee would apply inthe form of a transfer fee. Your local Class III dealer can easily walk you through either process.

Sources:

Synthetic Stock

Advanced Technology

102 Fieldview Drive, Suite 400

Versailles, KY 40383www.atigunstocks.com

(800) 925-2522

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V11N5 (February 2008) |