By Dan Shea

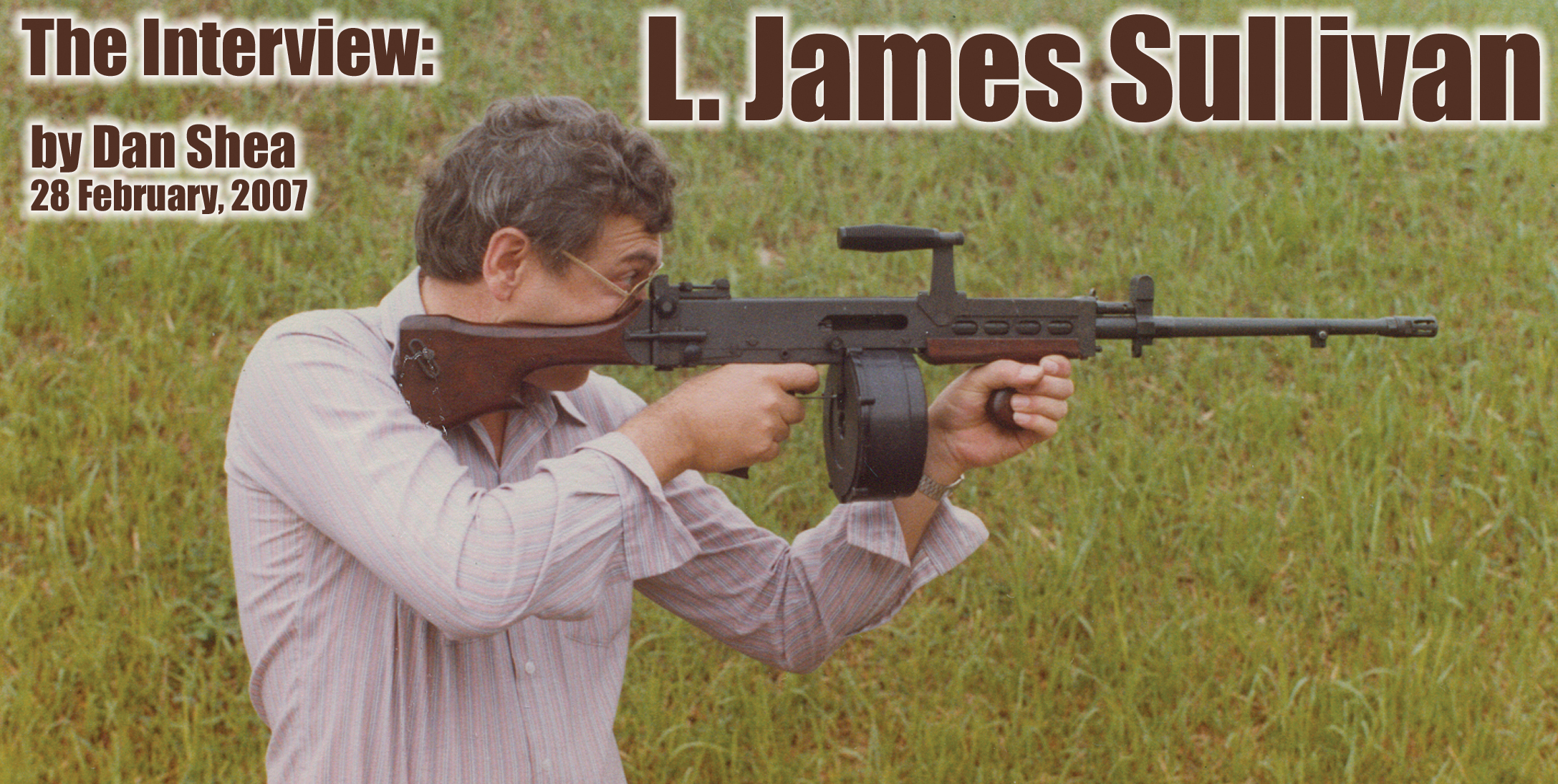

L. James (Jim) Sullivan was born on 27 June, 1933 in Nome, Alaska. His father was an attorney and Senator in the Alaskan legislature. He has one brother, Frank Sullivan, who is a doctor in Cranston, Rhode Island. He is married to his wife Kaye, whom he married while working for ArmaLite in the 1950s. The list of Sullivan accomplishments and designs in small arms is impressive and stretches from the AR-15 system, to the Stoner 63 system, the Ruger Mini-14, the Ultimax 100, and countless projects in between. Jim Sullivan is still going strong, and this winner of the prestigious Colonel George Chinn Award from the NDIA Small Arms Symposium, is forging ahead on new projects.

In Part I of this Interview, Jim Sullivan fills in the blanks on the ArmaLite days and the AR-15 project, the Stoner 63 project, digs deep on the Ichord Committee regarding M16 failures in Vietnam, covers the Ruger Mini 14 and M77, as well as his work on the 7.62mm chain gun, the EPAM, Chiclet Guns, and Caseless ammo.

SAR: Jim, how long did you live in Nome?

Jim Sullivan: Until I was seven, and then the family moved. It looked like the world was heading back into full scale war (World War II). Actually, it had really already started and it looked like the US would get into it and might head towards Alaska; so we moved down to Seattle. I went through grade school, then went to a town called Kinewagon, Washington, and then went back to Seattle’s University of Washington for engineering. I’m not a graduate engineer, but I took engineering courses there.

SAR: What was your first experience with firearms?

Jim Sullivan: I was 12 years old, and a friend of mine’s father had quite a collection and I used to go over there and just look at all those pistols. It was a very large collection and he had a firing range set up. He would fire them for us – he wouldn’t let us shoot, but we could watch. Most were military auto-loader pistols. The first time that I used any military firearms myself was when I went in the Army. I was in during the Korean War, from ’53 to ’55, and the war was already winding down at the time. They were having the Panmunjom talks, and the war ended by the time I finished basic. That was fine with me.

SAR: What was your MOS?

Jim Sullivan: I don’t remember the number. I had been trained as a telephone installer repairman, but I had also gone to what was called the Sparling School of Deep Sea Diving before I’d gone in the army, so I transferred into diving when I went overseas. That was in 1954. There was a lot of repair work to do after the invasion at Inchon. This was after the war. As far as firearms, the only ones that I fired at all were just in basic training, and we got everything: M1911A1 pistol, M1 Garand, M1 carbine, and the Browning machine guns. I didn’t see any odd machine guns in Korea.

SAR: Were you interested in those modern guns?

Jim Sullivan: I was fascinated by machine guns in general and I read everything I could ever find on the Maxim gun, especially the technology and the effects of World War One. This was long before I ever fired an M1 rifle. I had WHB Smith’s Small Arms of the World and a wonderful biography of Hiram Maxim. I read about him, and read quite a bit on John Browning and the German designers. I’ve noticed that most of the small arms advances were either designed by Americans or Germans.

SAR: At what point did you shift over to working with small arms?

Jim Sullivan: When I got out of the Army in 1955, I went back to the University of Washington, and I read about this new company called ArmaLite. I think it was in Time magazine. They had an article on the AR-10. I applied for a job as a draftsman there, and that’s how I started with ArmaLite – that was in 1957. I was never a good student, and I had gone to work for Boeing like half the people in Seattle. ArmaLite was something that really caught my interest and I was very happy to land that job. They were in Hollywood, California at the time, so I moved there.

SAR: Who did you work with at ArmaLite?

Jim Sullivan: I reported directly to Gene Stoner. Everybody did. Well, not everybody, because there was a front office staff. Charles Dorchester had some people up there, but everybody in the machine shop and the designers did. There were two designers at the time, John Peck and Gene Stoner, I was just a draftsman. Bob Fremont started later, and Art Miller was there already, but he was pretty much working at Artillerie Inrichtengen in Holland on the AR-10 program during the three years I was at ArmaLite. John Peck was one of the designers of the M-1 Carbine; he had worked for Carbine Williams and had actually worked there at ArmaLite before Stoner joined. He worked for George Sullivan – not a close relation to me and I never did discover how close we were. George Sullivan was the founder of ArmaLite. He was the patent attorney for Lockheed and got Fairchild. I don’t remember why that even though he was still in Lockheed, why he got Fairchild involved. Fairchild was the one that funded the Fairchild Airplane Engine Company, funding ArmaLite.

SAR: What type of projects did you work on at ArmaLite?

Jim Sullivan: I did almost nothing on the AR-10. They wanted to make another try at moving the gas system from the side to the top. The original AR-10 had it on the side. Gene asked me to take a whack at it, and I did. He didn’t like my idea at first because there was a transfer tube in the AR-10, and what we ended up with on the AR-16 and the AR-10 was that transfer tube was pulling off of the gas tube, and he thought it would add to the leak, and of course it does because it’s got an additional gap in there. Anyway, it worked. This was about a year into my time there, and I was promoted to Design Engineer. John Peck had designed an early .556 caliber gun. Actually, there were two guns made. There was one they called a Stopette, which was in .222 Remington caliber. It didn’t have a pistol grip, and it didn’t have a big enough barrel extension. The extension broke, and the head of the machine shop that was firing it was creased on the top of his head, and required getting patched up. The Stopette was originally designed by somebody who wasn’t there anymore, I think his name was Doc Wilson. John Peck was doing a military version, just a scaled down AR-10. What you might call a first AR-15 in a way, but it certainly wasn’t. It was smaller in diameter, it still had the same small barrel extension diameter as the one that had blown up. That project was stopped when the Stopette blew up. They had fired it all right, but it was the first of that size that we changed the gas system from the side. This too had the side gas system that I moved to the top. That was my only work on that project, and my only work on the AR-10. Since that worked well, I got promoted.

SAR: How was the work atmosphere at ArmaLite?

Jim Sullivan: It was great. The people were really sharp people, all of them, and fun to work with. Most had gun backgrounds. George Sullivan, the founder, had a big collection of military guns. John Peck certainly was a gun enthusiast, and Gene Stoner, well, you know his background on the early work on AR-10 before joining ArmaLite. People at ArmaLite were into guns and into the history and technology, and there was a good work atmosphere. I only had a Browning Pump while I was there. After the Stopette, they wanted to do an all new cartridge, a new gun, and that was what became the AR-15. This is the M16, basically the same gun, it’s just more evolved using two different numbers. We started from scratch, and there was another guy that joined me by the name of Bob Fremont who wasn’t a gun guy. Bob was one of these fussy guys that was exactly right most of the right time. He drove everybody crazy. He did the most meticulous tolerance studies. He would do that, and I was doing the gun design on this gun, they hadn’t even given it a name yet, but that was what became the AR-15. We put a different trigger mechanism in there. We made changes from the waffle magazine, which, while it looks stronger, it’s actually weakened by doing it that way. We had a 25-round steel magazine that wasn’t a waffle magazine. That didn’t last. With the 25 shot, the taper in the cartridge was a problem, so we went to the aluminum 20-shot to keep the mag straight. You can only go so far before you run into trouble, if you have a straight magazine. The AR-15 was designed for a straight magazine. In retrospect, that was a mistake. You really needed a curved magazine to make the weapon more effective. We never should have done it that way with a straight magazine.

SAR: What material did you use in the first AR-15?

Jim Sullivan: George Sullivan, the founder, he was kind of into new materials, and he had a version of 7075 aluminum that he called Sulliloy. Yes, “Sullivan Alloy.” [Sullivan laughs] I think he put some kind of patent on it, pretended it had special properties. Really, it was just 7075 aluminum with some kind of bat’s blood voodoo in it. Never made any difference that we could see.

SAR: How did the first AR-15 work? Did you get it built while you were there?

Jim Sullivan: Yeah, we got it done. Prototypes never work right, and we had lots of problems, but we solved them all. Actually, we had moved out of Hollywood by the time we got started on that one. We were down in Costa Mesa, which is 30 or 50 miles outside of Hollywood. The company was growing and growing. We had a great range that we could go to there in Hollywood. It was a little ways out of town. The Hutton range, but we lost that. The one we had that we were able to use there in Costa Mesa nearby had too many rules. You would have to make arrangements to go out there and fire, where at Hutton we could just show up and blaze away. That restricted the test firing, which in a way may have caused some of the problems that later showed up regarding the extraction business.

SAR: What were you doing personally?

Jim Sullivan: I got married almost as soon as we moved down there. Kaye had agreed to marry me already, so she came down immediately after I started there, and we got married right away. I worked there three years, through the entire process of the AR-15. After that, Bob Fremont got laid off, then I got laid off and Gene Stoner left. ArmaLite wasn’t really making any money, and ArmaLite had originally intended to produce this rifle. Stoner and some sales group had gone to Asia with an AR-10 and the new AR-15. Nobody wanted the AR-10, everybody wanted the AR-15. Strangely, Stoner never thought much of 5.56 caliber. He’s called the father of the 5.56, but he didn’t like it. He designed the AR-16, which was a 7.62 rifle using a piston version which went no place, but the scaled down version in 5.56, the AR-18, was the one that was successful. That was Arthur Miller’s project after I was gone.

SAR: Did you stay in the firearms business after you left ArmaLite?

Jim Sullivan: No, I went to National Cash Register: it had nothing to do with guns. I was a designer there for two years, and then I wanted to get back into guns. I went to work for Harvey Aluminum, which made Sulliloy, the 7075 forgings. Here’s one of the first ones. (Sullivan pulls out an AR-15 lower receiver forging.) That’s the first AR-15 forging. It was from a group of 40 that we did. I also got involved with explosive munitions that helped me get some background in this area. It was for an earth anchor; it wasn’t demolition or weaponry. You pounded a pipe in the ground, then you dropped this little bomblet down in there, and set it off. It would spread open, and then you’d drive it down one and a half feet further into this empty space down there, and then they poured concrete in. This was something they could anchor aluminum. They were special little pallets that joined together and made an airfield and it was for anchoring an aluminum airfield. So to sell their aluminum airfield, which the military adopted, to sell that, they had to develop this earth anchor, and that’s what I was involved with. It was adopted in the early ’60s.

SAR: You joined Gene Stoner on the Stoner 63 project at the beginning, didn’t you? Where were they at when you joined them?

Jim Sullivan: Bob Fremont had joined him too, so it was the three of us, the same three that had worked on the AR-15. Bob worked on the Stoner 62; I never did that. It was 7.62 caliber like Gene’s M69W prototype. M69W reads the same whether it is in a standard machine gun version or with the receiver inverted to become a rifle. I joined in on the Stoner 63 at Cadillac Gage in Costa Mesa. All of these projects, the M69W, the Stoner 62 and the Stoner 63 had similar concepts. If you turned the receiver upside-down, it was a rifle, turn it the other, it was a machine gun. I worked on everything in the project, but each of us did different things as a focus part of the project. We were no longer doing special cartridges, so that was a little different. Bob Fremont concentrated his work on the machine gun parts, the belt feed, and I worked more on the magazine-fed gun. Of course, they’re the same gun, so whatever one guy was doing had to be compatible with what the other guy was doing. At this time, Colt was making the AR-15 and M16. ArmaLite was shut down as a division of Fairchild and was sold off to some guys in Texas. They had sold the AR-15 gas system patent to Colt.

SAR: Were you following what was going on with Colt and in Vietnam?

Jim Sullivan: I wasn’t getting any special briefing on it or anything, or aware of what was going on. Where I became aware of it was when everybody else did, the scandal of American soldiers being killed with jammed guns, being overrun. I didn’t know what the problem was at the time, nobody knew when that first hit. I mean, the people in Army Material Command apparently knew, they had to have known, but they didn’t volunteer any information. [laughs] I mean, those people, still today I think they must worry about what would happen if anybody really found out what they had done. Nobody can prove that they sabotaged the M16 program, but there was no way that, in the testimony that came out in the Ichord Committee that this was a complete unknown. I feel very, very strongly on this. (Senator Ichord headed the committee, which was the 90th Congress, 1967. The report is titled “Special Subcommittee Report on the M16 Rifle Program, House of Representatives” dated October 19, 1967). Essentially the problem that happened with the M16 in Vietnam was that they changed ammunition from what we had designed and they went and changed from IMR powder to a ball powder. I can find the conclusions here “Increased cyclic rate caused by ball propellant,” it goes into that waver of cyclic rate of seconds test. The problem was that they changed from the intended powder. Who did that change? Army Materiel Command at the time did not have the ammunition. They had guns under their control, but not ammo, which was stupid, just an organizational problem. But they were in charge of the guns and the arsenals. Ah, here’s the findings and recommendation of the Ichord Committee Report.

“Both the Army and Marine Corps personnel have experienced serious and excessive malfunctions of the M16 rifle, most serious being the failure to extract a spent cartridge, that the past experience of the army with the M16 rifle in Vietnam was not properly called to the attention of the Marines when the weapon was issued to them. That the major contributor to malfunctions experienced in Vietnam was ammunition loaded with ball propellant, that the change from IMR-extruded powder to a ball propellant in 1964 for 5.56 ammunition was not justified or supported by test data. That a number of modifications of the M16 rifle were made necessary only after ball propellant was adopted for the 5.56 ammunition, that the AR-15/M16 rifle as initially developed was an excellent and reliable weapon.”

It went all to hell just because of that change in propellant. Certainly there were other problems. We should’ve chrome plated the chamber, that causes problems, and that was something that was our fault as original designers.

SAR: What were the symptoms of the ball propellant change that happened to the AR-15 M16 system?

Jim Sullivan: It has much higher gas port pressure. It’s not in itself a bad powder, it’s just like saying diesel fuel is fine, just don’t put it in a gasoline engine, and that’s what they did. The gun has to be designed for the powder. That’s the fuel that the gun as an engine runs on. The M16 system was functioning just right, but when the powder was changed, the gas port pressure that operates the gas system that operates the bolt had much higher pressure. It made the bolt move faster than it was designed for, and it began unlocking too early, which put stresses on the locking lugs. Also, the cartridge metal hadn’t relaxed in the chamber enough, particularly when the weapon got hot, and the cartridge would stick in there, keeping the extractor from extracting the cartridge. The extractor would start to pull it out and then pop loose occasionally. In a weapon, you can’t have occasionally. These weapons would reach a point where a guy couldn’t fire a full 20-shot magazine through ’em. Initially with the IMR powder that we designed it for, it was 10,000 psi at the gas port. The ball powder was 12,500 psi, a 25% increase. That was enough to make the gun not work taking the reliability factor out of the equation. Ball powder’s also dirtier than IMR, and the M-16 is dirty as well because the gas system goes back into the upper receiver area. I mean the gas actually operates the gun, way back at the back of the bolt, the bolt gets dirty because of it, and it requires more attention. With IMR powder, which is a cleaner-burning powder, it was a lot better. I can’t name numbers on that, but I know, I’ve seen the tests, and it’s a lot easier to clean with IMR. The US is still using ball powder in the 5.56 cartridge: they should’ve changed it immediately. Foster Sturdevant from Colt came up with a heavier buffer. It was more than just heavier, that’s what slowed it down, but it had another kind of unique feature which was neat, and that was the heavy weight that’s within this tubular buffer was divided up into a bunch of sections that were separated, and they were steel cylinders separated by a rubber washer. And so they had a cascading effect of impact. When they’d impact at either end, you didn’t get the impact of all of them at one time, it was “bang bang bang bang.”

SAR: It spread the impulse over…

Jim Sullivan: Exactly. It spread the impulse over time. It worked. It saved the gun, but it didn’t work perfectly. As gas-operated guns get older and get more rounds fired through them, the gas port rounds off inside. When you drill the hole that is the gas port, it ends up with sharp corners where it breaks through into the bore. Gas doesn’t like to flow around sharp corners. As you fire more and more ammunition through it, it wears those corners and rounds them off, and now gas flows faster and faster. The gun as an engine is speeding up. The older it gets, the faster it goes, and the more powerful the cycle becomes. A lot of people think that’s good, breaking it in. Wrong, this is bad. A gun has to work within a certain zone, the action has to be right, the spring, the weight of the cycling components, the distance you’ve given them to cycle and the spring force. You get that too far wrong, and the gun doesn’t work anymore.

SAR: There’s a positive break-in period on the gas port.

Jim Sullivan: Certainly. It’s drilled in there, and that wear-in is going to happen naturally within 1,000 rounds no matter what you do. We plan for that. It’s the abuse that causes the problems. Some of the special operations groups, they do their training and they fire massive amounts of ammunition, they get their new M4 Carbines, and their doctrine is suppressive fire going in and coming out. They do mag dump after mag dump after mag dump.

SAR: Some of those used guns I’ve clocked at 1,300, 1,400 rpm. Is it just that the gas port is rounded out and the flow is better, or is it that they’ve actually eroded the hole, and they have more going in there?

Jim Sullivan: The diameter doesn’t change, it’s the rounding off. There are two things about this event. The gas port in the M16, we didn’t know about this. A lot of the US gas operated guns, the BAR for example, had gas port adjustments on it. You can let the gas port be the initial throttle, but you can compensate for when it rounds off. But in a gas operated gun, if you don’t have a gas adjustment on there, you can’t use the gas port diameter as the metering diameter. You’ve got to go downstream someplace and put something smaller in there that can’t erode that remains the metering diameter. We didn’t have anything like that in the M16, that part was our fault, we didn’t know it needed to be that way. I went to Colt about the M4, and took the plug that’s in the end of the gas tube and I moved it over this hole, and I made it the restricting hole diameter. No matter how big you make the gas port, or how rounded off it becomes, it’s the hole that is in the gas tube that does the metering and determines how much gas gets back here. More is still going through, but its way better to do it that way.

Remember, going back to the Ichord Committee in the 90th Congress, they identified the problem with our soldier’s weapons. The 110th Congress doesn’t even care. They don’t care that the M4 has got exactly the same problems that this thing had in ’67. Back then, people raised all kinds of hell over it. The 110th Congress doesn’t do a damn thing, and those soldiers over there in Iraq right now have exactly the same problems with their M4 in spite of the improved buffer. They’ve got exactly the same problems that this thing had in 1967 when the Congress actually did something about it. These people won’t. The United States militarily is in bad shape because they’ve let these small arms deteriorate to a point now where the US is a superpower only when it fights a naval battle or an air battle. It’s not a superpower when it fights a rifle battle.

SAR: You worked on the Stoner 63. How long were you with Cadillac Gauge?

Jim Sullivan: Three years there, too. The 62 was a prototype for the Stoner 63 but the 62 had a machined receiver while the 63 was a sheet metal concept. The trigger mechanisms were very different. What made the gun unique and valuable was the fact that you could assemble it as a rifle, or using 90% of the same parts you could assemble it as a full-performance machine gun. That concept had been worked out on the 62 by the time I had gotten there. I worked on scaling it down into the 5.56 caliber. We had lessons learned from the AR-15/M16 project that we could draw on. We needed a longer cam and we put a longer dwell in the unlocking cam. No matter how fast the 63 may speed up, it isn’t going to seize up. I don’t think we ever had an extraction failure in the Stoner 63. It isn’t the angle of the cam path, it’s the straight section. If you make the straight section longer, the bolt carrier has to move further before it begins to rotate the bolt, and the overall total length when it’s all done and starts yanking on the cartridge is determined by the overall length of the cam. The longer that is, the more the gun likes it, and that’s true of any auto loading gun.

Of those three years I was there, two years were spent designing the Stoner 63. Bob Fremont left in that time period and went to work for Colt. Bob was a great guy, but he bullied the front office and he insulted the executives. [Sullivan chuckles] It was kind of fun to watch the fight going on between Fremont and the execs. Fremont was a hell of a good man, but he was hard to take. I liked him, but a lot of people hated him. The execs sure hated him. We were still in California, and the president of the company came out and he was really steaming mad. I don’t remember what Fremont had done that day. Anyway, he flew out to California to fire him. Fremont knew he was coming, and when the guy was there, he walked in our office and asked for Stoner to come outside, and Fremont says, “Wait a minute. While we’re all together, there’s something I’ve got to talk about. I’ve been here for two years now, and I haven’t gotten a raise yet.” [laughs] The guy was so shocked he gave him a raise and left. [laughs]

SAR: A preemptive strike?

Jim Sullivan: Yeah, Stoner and I just roared. Stoner had told us the guy was coming out to fire Bob.

SAR: You were two years into the Stoner 63 program. How many guns had you made?

Jim Sullivan: We had everything worked out. We made about 80 or 85 guns at that point, and then I went back to Quantico and spent that year there. It was all testing with the Marines at Quantico, and Camp Lejeune, and then on up to Fort Greeley, Alaska for cold weather testing. The Marines liked the Stoner 63. In 1965, they did a live combat test in Vietnam. Colonel Joe Gibbs was the man who ran the tests in ‘Nam. Recently, he wanted to do a book on the Stoner 63. But the Marines made few changes to the gun and you know the old saying, if it works, don’t fix it. The Marines tested the Stoner 63 for a year and then ordered 300,000 of them, and the Army talked to Congress or the Senate funding committee and said, “The Marines should use what we use,” and that ended that. The Marines loved the gun, they didn’t want any changes to it. In the testing, certain problems came out. At Fort Greeley in Alaska, the machine gun wouldn’t work at all and we had to make a little fix. Remember, you turn it upside-down if it’s going to be a rifle, from where it is a machine gun. There’s a turret at the back of the bolt carrier. When you turn it upside-down you have to rotate that so that it remains in the same up and down position, even though you’ve turned the bolt carrier over. In order to be able to turn that turret, it was just bound in there tight by the buffer, which was part of the bolt carrier assembly. It was just held in position by friction, and then when you put it in the gun it was held in position by the track. In severe cold weather, you’ve got problems with lubricants. A gun needs to be fairly well-lubed. Up in the Arctic you have terrible friction problems because the lubes don’t work in extreme cold weather. They rub off, and you’ve got chist in the air – ground up powdery stone from shifting ice floes. This gets in the action. Anyway, this turret, which was positioned by friction, would under normal circumstances move forward and move back, because it was operating the belt feed. The feed was camming to one side, causing it to rotate to the other side. It would seize up and stay there, and the gun couldn’t cycle, in an almost cold weld. It became obvious what the problem was, and I did a little latch that prevented it from locking up. It was a positive latch, and then Stoner came up with a simpler way. I talked to him on the phone about it. It was to take advantage of this stack up of buffer forces. It had to cam itself forward to compress these Belleville washers a little further, and then would snap in. It was a detent using parts that were already there. We never did get it fully tested. This is typical of the type of problems that would show up in field tests, that don’t show up in your normal tests.

SAR: Did you travel outside the US for that period?

Jim Sullivan: No, most of the travel I did in that group was testing in US military type places. Cadillac Gage moved to Warren, Michigan and I was there for a year and a half. I was in contact with all kinds of people in the firearms industry as by that time I had gotten to know a lot of people. Stoner and I had gone to an army briefing on small arms, and Bill Ruger was there, so the three of us went out to lunch. Afterwards he offered me a job, and I wouldn’t have taken it. I would’ve stayed at Cadillac Gauge, but the Army turned against the Stoner 63 order for the Marines. Not much point in sticking around. The Stoner 63 project was pretty much relegated to minor production. Maybe 3,500 guns total. They made changes to it, and by the time that test was done, it was as near perfect as you could ever make a gun. The users didn’t want any more changes to it at that point, and Cadillac Gauge just couldn’t keep their hands off of it.

SAR: So you moved over to Ruger. How long were you there?

Jim Sullivan: 1965-1968. Three years at Ruger too.

SAR: Three years. Jim, I’m detecting a pattern here.

Jim Sullivan: I know. [laughs]

SAR: Where were you at with Ruger?

Jim Sullivan: That was in South Port, Connecticut. I was an engineer and a designer. I designed two guns: the model 77 bolt action and the Mini 14. That Mini 14 was the third 5.56 that I had worked. I worked with Bill Ruger. Everybody worked with Bill Ruger. There were two guys on the Mini 14 project. The chief engineer and another guy named Larry Larsen, who was at the time doing the single-shot rifle; that beautiful falling block rifle, the Ruger Number One. What a beautiful gun. Actually, that’s what Larry worked on the full three years. It sounds funny that a gun like that takes more design time than a bolt action repeater or a Mini 14, but it does. Everything’s got to be perfect, and it was.

SAR: You worked on the Mini 14. What did you start with when you were looking at the project? Did Bill Ruger have a concept?

Jim Sullivan: The Mini 14 was just a scaled down M14. That was it. Ruger said, “Let’s take an M14 down to 5.56.” The M16 had been adopted, and what Ruger wanted was something he could sell to both the military and civilian world. I tried to tell him the military wasn’t going to buy a 5.56 that looks like a hunting rifle; it’s got to be an assault rifle. The full auto gun, the AC-556, was done after I left. I did it in semi-auto.

SAR: How was it working there?

Jim Sullivan: Oh, just great. Bill Ruger, you remember what kind of guy he was, he was a curmudgeon. So a lot of people were afraid of him, I guess, but he and I got along good. I worked for him again here in Arizona. I spent about an equal one and a half years on each rifle I did at Ruger. On the M77, when you looked to the market, there’s the Winchester Model 70 and the Remington 700 as main contenders. Bill wanted something as good as the old Model 70. He didn’t want something cheap like the newer guns on the market. He wanted something that would compete. Bill wanted something that’d outsell them both, and it did. He wanted a better gun, and he had bought that casting company in New Hampshire, Pine Tree Castings, and so he wanted the bolt and receiver cast, and he wanted top quality. He wanted a Mauser-type extractor, so it’d be a full controlled-round feed. In the end, it really wasn’t, we cheated. It looks like a Mauser extractor. It snaps over, though, it doesn’t slide up in. Then he wanted his own proprietary scope system, so I had to come up with the tilt-out scope,

SAR: How was the Mini 14 project? Was that challenging?

Jim Sullivan: Yeah. I thought that was more interesting. The only thing you get to do as a designer that’s kind of novel and fun is like the trigger mechanism on the Model 77. I came up with a different way to do it, as well as the bolt stop. We got a patent on it because it works just like a Mauser bolt stop, but the Mauser bolt stop has to have a bump out of the receiver, which makes it real hard and expensive to polish that side of the receiver. I came up with a bumpless stop. [laughs] So that was fun. The rest of it had all been done before. Anyway, I loved Ruger, I loved the company, it was great, but Kaye and I didn’t like Connecticut. We had two young kids going to school. We really wanted to get back to California, and I got an offer from Hughes. I went to work there and stayed for 10 years. That broke the three year curse. (Laughs)

SAR: Hughes Advanced Armament Division of Hughes Tool?

Jim Sullivan: Yes. I was one of the designers of the first chain gun in 7.62mm. I didn’t work on the upsized M242 25mm guns. They use ’em on helicopters and the Bradley Fighting Vehicle. The 7.62mm, it’s on the main battle tanks in England. There was a 30mm chain gun project as well, but the Army was saying, “We want proof of concept” so I was brought in to make a 7.62mm chain gun. Hughes had been working on a twin barreled Heligun with a revolving cylinder in between the barrels, but that wasn’t my project.

SAR: Was the chain gun your concept?

Jim Sullivan: I didn’t invent the chain gun, a guy named Lenny Price was the inventor: it was his concept. Originally they didn’t have me come out there to do the chain gun. What they wanted was a tank machine gun because there was the old Browning .30 caliber gun that was too long, and a new very short receiver .30 caliber tank gun, called the M73. What a piece of garbage, along with its big brother; the M85 in .50 caliber. What they wanted to do was replace the M-73. There was a big broad agency announcement of a requirement for a tank machine gun that would go in all mechanized vehicles. Hughes worked on several projects to address that. One of them was the chain gun 7.62; the other one I worked on was the EPAM, the Externally Powered Armor Machinegun.

It had a hand crank on it. That was just one of the requirements, kind of silly, I thought, but they said if power failed, you’d still want to be able to use it. Kind of dumb in my opinion, but hey, it’s a requirement. All the EPAM ever was, was a prototype. Lenny Price came up with the chain gun at the same time. In the Hughes Times, they wrote up that he got the idea from a Harley Davidson motorcycle. He was a Harley rider, so of course he knew chain operation, but that wasn’t what set him off. He was another neat guy. A lot of the guys that I’ve known that were gun designers, were exceptional, interesting people. They did all kinds of things. This was in Culver City, California, and Lenny lived on a boat, and he went to work on his motorcycle. I’ve ridden on the back of that many times, went out to lunch with him a lot of times. Neat old guy. He’s dead now, like so many of them are. He started off with a bigger gun for a different requirement, and the chain just fell into place as a natural way to shorten the mechanism. While he was in the middle of this, the Army had a requirement for a helicopter, and the Hughes Helicopter Division wanted something in 7.62mm. If they could do the gun and the helicopter, that would give them the contract. They started in on that while I was working on the EPAM, and Lenny was working on the 30-millimeter. The army’s “proof of concept” speech was given, and they wanted to see the thing. Hughes asked me to drop the EPAM and do a 7.62mm chain gun. I started off on that all by myself, but there was a guy who is now kind of my partner in some of the stuff I’m doing: Bob Waterfield. Bob worked at the range as a range technician. He’s really sharp, and I got him involved. The two of us ended up co-designing the 7.62mm chain gun. We did start with scaling down Lenny’s chain drive, but we had to do the rest from scratch. Americans didn’t do anything with it, but the British did. They liked it because we did a forward eject on it and it had that short receiver footprint. We got that done before they got the 30-millimeter done.

SAR: What’s the concept on the chain drive?

Jim Sullivan: When you look down into the receiver, you will see a chain that goes around four sprockets in kind of a rectangle. You have all the dwell while the connector to the bolt is going side-to-side, and then the motion of the bolt is when it’s going front and back. When it’s going across at the rear, that’s when you do your feeding. When it’s going across at the front, that’s when you do your firing because it gives you time for the pressure to drop in the chamber. This system has been done at higher rates of fire, but is really only effective at a lower rate like about 450 RPM. Remember, this was the period where they were working on the new tanks and some of the new vehicles, and they didn’t want to have the long receiver Browning 1919 series or the long receiver .50 caliber. They couldn’t get the commander in there near the gun, because it was too long into his face. They had to make guns with shorter receivers, and the two that they had, the M-73 and the M-85 were just disasters as guns. On the chain gun, we laterally transferred a lot of the activity in the firing cycle, so our design was very short, and very effective.

SAR: That only covers about half of your time at Hughes.

Jim Sullivan: There was a lot of other work that we did. For a while the army was just fascinated with caseless ammunition. They couldn’t face the problems in caseless ammo, and they just believed that if they threw enough money at it, somehow it’d get solved. They’re still fighting with caseless ammo concepts. I worked on that and the Chiclet stuff as well as the Advanced Combat Rifle (ACR) concept and later the Advanced Infantry Weapon System (AIWS) at McDonnell-Douglas. The whole group of Hughes people went over to MDHC, in fact, after I came back from wherever, I went and did another Chiclet gun with them. It was recoil operated to soften it. It was like .410 caliber, only it was a Chiclet, that size, fairly big. It used five flechettes in a sabot, which in turn was in the Chiclet. The magazine went in the side and was semi-auto.

All in all, I spent about five years on caseless ammunition, Chiclets, all this hopeless crap. When you first get involved in it, you think well, the advantages are so great that it’s worth the effort. But when you get into what the problems really are, eventually you see it’s hopeless, and then you try to tell everybody that, and they get mad because they don’t want to give up their work or contract. With the technology that was available, and we’re in the same position right now, caseless became evident to me and the other guys that it wasn’t going to be able to be feasible. Really, you have to redesign what the goal is. If you say you want lightweight ammo, well, now you can work with that goal. If you say right off that the lightweight ammo has to be caseless, then you’re screwed. The guns were kind of fun, but man, they all ended up the same way. The breech seal would fail and blow up the whole magazine. We had some real wreckage down there!

SAR: So from 1968 to 1978 you did the EPAM, the 7.62mm chain gun, caseless projects, chiclet/flechette projects, and then left for…?

Jim Sullivan: There were plenty of other projects, but I finished up on the chain gun just before I went over to Singapore. I had kept in touch with the people at ArmaLite, which had been bought by a group of Texas oil men. I actually had an office at ArmaLite. Bob Waterfield joined me there on weekends, and we’d work there three nights a week and Saturdays. We formed a company called Timberline Hawk. We did just real simple things that we could try to do business with. John Wayne invested in this one program – this one here. It was a .22 LR rifle. We formed a corporation called Wayne Repeating Arms, and the plan was we’d start with a .22. Here’s one of them. (Hands over the rifle.)

SAR: Very lightweight.

Jim Sullivan: It had some nice features along with that. It locked open. At the time, California had the law about you can’t have ten-shot detachable magazines. So you could load the magazine. It’s a double-column magazine, you just load it through the port, you lock this open with the safety, then you release the safety in the chamber. It still operates as a safety. We incorporated, but we never got it in production because Wayne’s son-in-law was his business manager, and got caught in an “indiscretion” and Wayne fired him. The new business manager had to take over all the Wayne businesses, and since this wasn’t progressing in far enough, they just canceled it. So, too bad. I interacted with Wayne: we went out and he shot ’em twice. One of the ways we originally connected was we had started out as Timberline Hawk. We had made a little money, and we bought a bunch of parts from a company that had gone out of business. It was a little Derringer. Using their Derringer, I came up with a little .22 rifle. It’s pretty crude, but John Wayne ended up with one of the prototypes and took it out on his boat. He knew the people at ArmaLite because his boat was always being repaired by the boat yard next door, and he used to come in there since he liked guns. We had met long before, when way back when I had worked for ArmaLite. He used to go out and plink cans out in the water with it, and it turned into a business deal.

SAR: So that was the night job, three days a week?

Jim Sullivan: Yeah. It was an attempt to start up something more serious. We ended up with a shotgun that ArmaLite had made. John McGurty was their machine shop manager, and he was my partner on that gun that John Wayne ended up with. John McGurty, was a partner on the project. We also did a holsterable submachine gun. Here it is.

SAR: A holsterable submachine gun?

Jim Sullivan: Yup. Some parts were somebody else’s, but in our design, the bolt traveled a long distance and was very smooth. We made it so you could push from both ends, and now they put this all in a holster. It’s a telescoping wraparound bolt around the front, and a rear piece that comes together, closes up and becomes the size of a regular handgun. Pretty slick. We didn’t cheat and fire full auto, we didn’t have a license for that, we just fired semi-auto. It started its life as a Linda or Terry Pistol.

In Parts Two and Three of the Interview with L. James Sullivan, we cover Singapore and the design and adoption of the Ultimax 100, the Beretta Assault Rifle, the Beta C-Mag, Gordon Ingram, Somalia, Uzi Gal, the Ruger SMG, Kalashnikovs, the British SA80, “sacred cows” and his current design work, Jim takes a no-holds-barred look at the current US M4 issues. Don’t miss it!

L. James Sullivan’s favorite quote on wishful thinking in an Arms Race: The Spanish admiral talking about the Armada with his men, and how he was going to face the British and said that he knew that although the British had more range in their guns, God was on the side of the Spaniards, so the British would be befuddled and not able to fire until they were within equal range of the Spanish guns.

L. James Sullivan’s favorite quotes on preparedness: 1906 – Mark Twain, in reference to the Ordnance tests of the Maxim Machine Gun that had been ongoing since 1896: “The eye that never sleeps might just as well, since it takes ten years to see what any other eye can see in five minutes.”

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V11N6 (March 2008) |