by David Albert

As depression era unrest captivated the country, law enforcement of the 1930s struggled to cope with gangsters, strikes, and unruly mobs. Circumstances of the times drove innovations in support equipment for police to more effectively deal with the problems. Charles Manville, who operated a machine shop in Indianapolis, Indiana, had witnessed rampaging Midwest crime during the 1920s, and subsequently contributed to several self defense and law enforcement innovations. What began as tinkering for Manville developed into a niche business where he achieved success marketing his invention of progressively more efficient tear gas delivery equipment. His efforts expanded and sustained the small company he founded, known as the Manville Manufacturing Company, until wartime contracts for other products eclipsed his interest in the gas gun business.

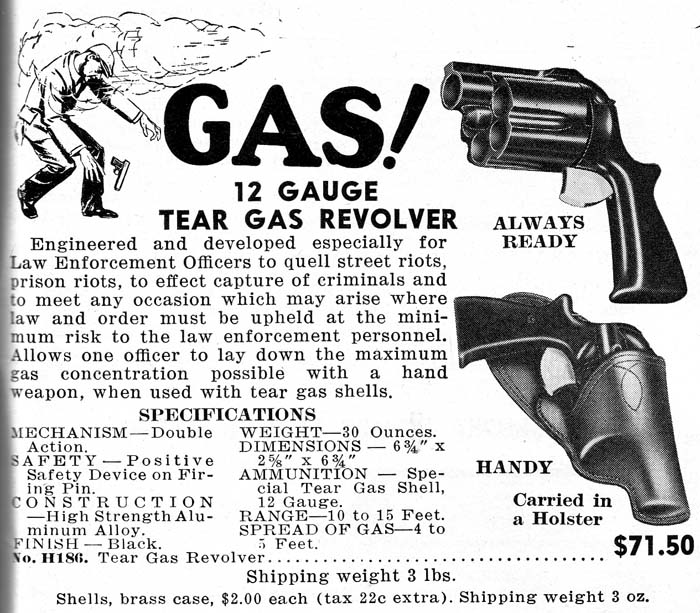

Manville began by developing personal defense equipment, leveraging the public apprehension of the time. He manufactured and marketed gas pen guns, which were concealable devices that a potential victim could use to project a small tear gas cloud on an attacker. They sold well enough to sustain the business, and he graduated the line to include pen guns ranging up to 12 gauge. Manville also began manufacturing cartridges known as “Manville Tear Gas Shells.” The Manville ammunition featured brass cartridge casings, and utilized non-corrosive primers and a DuPont powder charge to expel and vaporize a white crystalline chloracetophenone (CN) tear gas substance. CN was a short duration tear gas that produced intense tearing, eye pain, and skin irritation. According to Manville advertising, their tear gas formula was developed through 12 years of research by Captain Frank B. Gorin, formerly of the U.S. Army Chemical Warfare Service.

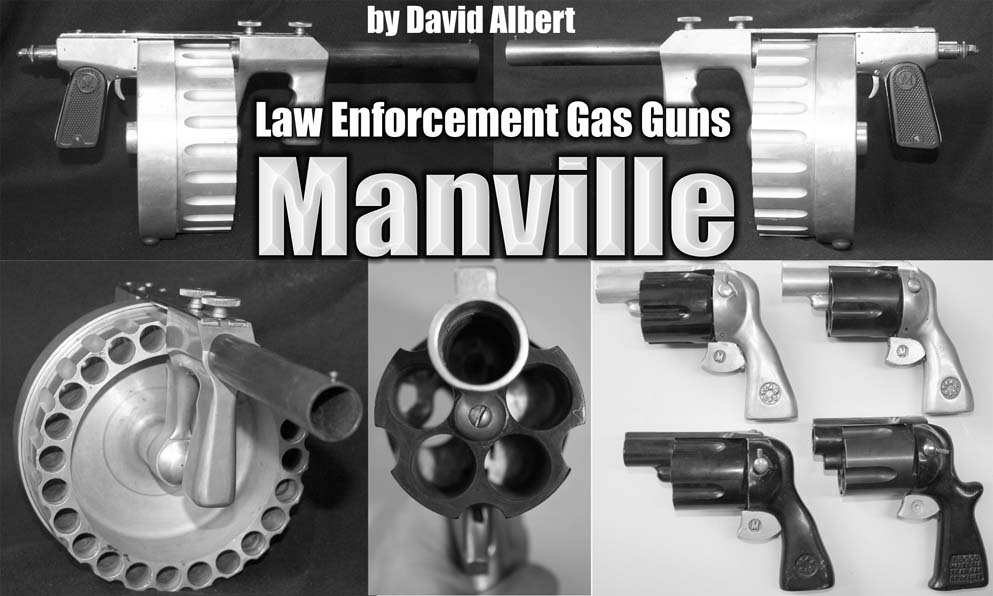

Manville began with the pen guns, but was disappointed with their overall effectiveness, so next he developed a 5-shot, 12 gauge tear gas revolver, designated the Manville Gas Revolver Model R12. The revolvers were marketed to law enforcement, who sought better means to deliver chemical riot control agents. While the 12 gauge gas solution still lacked the desired effectiveness, the ability presented by the Manville revolver for an officer, or team of officers to each fire 5 shots in quick succession improved their non-lethal deterrent firepower. Three examples of Manville revolvers were examined and photographed for this article, as well as another version marketed by a subsequent company. Various minor revisions occurred to the revolver design in the late 1930s, which can be seen in the examples.

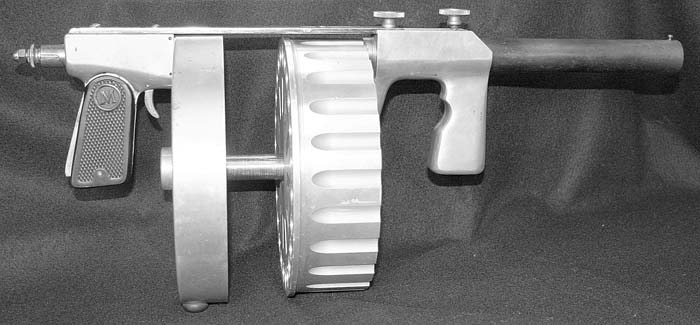

Manville’s quest to provide law enforcement with the means to deliver larger volumes of tear gas led to his invention of a 24-shot, 12 gauge, semiautomatic tear gas projector. The bulky weapon had a shiny, futuristic look, and also somewhat resembled the Model of 1921 Thompson submachine gun, with the Manville’s large revolving cylinder mimicking the looks of a Thompson “C” drum. The design was intended for hip firing and featured a forward grip, a shotgun bead front sight, and no buttstock. The Manville was crafted mostly of machined aluminum castings, with a steel barrel and frame support, and plastic grips. It was known as the Manville Machine Gas Projector Model M12. The Model M12 also had the ability to fire regular 12 gauge shotshells, which gave the gun a devastating potential at close range. There are no known instances of the weapon’s use with shotshell ammunition by law enforcement in a tactical situation.

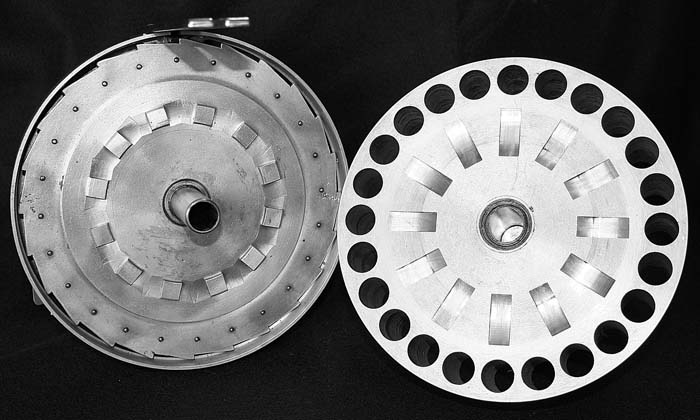

Manville Gas Projectors were produced in 3 design generations. The first generation, 12 gauge model exhibited a spring-wound, revolving cylinder milled out of a solid piece of aluminum, fluted to reduce weight. Manville named the aluminum alloy used in his revolvers and projectors “Manvilloy.” In order to reload the 12 gauge projector, the front and rear sections had to be separated by loosening two knurled knobs on top of the weapon, which clamped down on a steel receiver support rail, just forward of the revolving cylinder. This was an awkward and tactically inefficient operation. The violence of the action also tended to work the knobs loose, producing wear at the joining surfaces, and causing the halves to slightly separate. As a result, ill gas effects for the shooter could occur, since tear gas cartridges of the time activated immediately upon firing. The preferred firing position was most definitely upwind from the desired target.

Several of the Manville revolvers and projectors were reportedly used to help subdue a labor riot in Terre Haute, Indiana in 1935.

When Manville designed the larger 25mm guns, the weight of a solid 25mm aluminum cylinder would have proven unacceptable, so a shorter aluminum base cylinder was machined to accept 18 steel sleeves, which protruded dramatically, adding to its shiny, futuristic look. Some other improvements were made to the action, while the weapon retained the two knurled knobs on top, keeping it necessary to separate the two halves to reload. These were the second generation of Manville Gas Projectors.

The third generation of Manvilles featured improvements to facilitate easier reloading. A pivot tube with an internal bolt action was added above the receiver, connecting the front and back halves of the gun. The tube acted as a pivot point, so that the cartridge cylinder could be swung out and reloaded, without separating the two halves. The bolt action served to lock the halves together after loading, which solved the separation and tear gas exposure problem existent in the first two generations.

Several misperceptions exist regarding the Manville Guns. The first misperception is that the weapons were fully automatic. This probably originates from the Manville Model M12 designation as a “Machine Gas Projector,” and also from the Manville chapter in Thomas Swearengen’s 1978 book, The World’s Fighting Shotguns, in which a picture caption refers to the 12 gauge, 24-shot model as the “Manville 24-Shot, 12 Gauge Machine Gun,” although the text specifically documents the action as semiautomatic. The 12 gauge specimen examined for this article was not designed for, nor capable of, fully automatic fire. Manville and Swearengen probably perceived the gun as a gas projecting machine, thence a machine gas projector, or gas delivery machine gun. The second misperception involves the existence of an 18-shot, 27mm model, and a 26.5mm model. Information and pictures of supposed 27mm Manville Gas Guns exist on the internet, but the models referred to are actually 18-shot, 25mm Manvilles. The root of this lies in the fact that Manville referred to the guns as 25mm, but measurements of a second generation, 18-shot, 25mm Manville demonstrated the muzzle and chambers measure between 26.6 and 26.75mm. The gas projector models were also not marked with caliber designations until the 3rd generation.

Improvements to tear gas ammunition occurred during the late 1930s, particularly with the larger cartridges. Fuses were incorporated to allow aerial or point of contact gas ignition. This was certainly good news to law enforcement who deployed the gas. Manville became involved in these improvements, and in his quest for continuous improvement, he developed a 12-shot, 37mm version of his gun, featuring a removable, revolving magazine. Realizing that the size and quantity of 37mm gas would be too heavy for a hand held unit, Manville designed it with a ground mount, similar to a Maxim machine gun. This essentially made the gun into a crew served weapon, at least in terms of portability. The 37mm model did not sell well, and no examples were available for review.

The Manville Manufacturing Company went public, changed their name to the Manville Manufacturing Corporation, and moved from Indianapolis to Pontiac, Michigan in 1935. During WWII, they produced parts for 20mm aircraft guns, and were awarded the Army-Navy Production “E” Award for excellence. The award was a coveted and patriotic achievement for companies of the time. After the war, Manville produced dishwashers, and later ceased business. It is important to note that little documentation remains regarding the Manville company, as Charles Manville reportedly destroyed all records, prototypes, tools, parts, and complete guns on hand in 1943. Swearengen’s shotgun book included a chapter of information he gained from interviewing former Manville employees, and we have him to thank for providing much of what we now know about the development and history of the Manville gas guns.

Following WWII, Lake Erie Chemical Company (LECCO) acquired patent rights from Manville, and manufactured their own version of the 12 gauge, 5-shot tear gas revolver, and called it the Model 512. The LECCO model was marked accordingly, and added a hand stop at the top of the revolver grip to aid in control during repeated firing. The hand stop enables easy identification of a LECCO model at a glance.

Manville influences on current firearms can be found in some available revolving models of 37mm tear gas guns, as well as the 40mm MM-1 grenade launcher developed for the U.S. Military during the 1970s. Probably the most widely known Manville influence occurred when Hollywood cast a third generation Manville Gas Projector in the 1981 movie, The Dogs of War. The flashy weapon was featured prominently in advertisements for the movie, and its abilities as portrayed were quite exaggerated. Although Charles Manville inexplicably abandoned and obliterated record of his gas gun projects, the design features he incorporated into each model he produced still have relevance to law enforcement and military products today.

(The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the late Thomas Swearengen, author of “The World’s Fighting Shotguns” and Ironside International Publishers, Inc. for certain information referenced in this article, as well as William J. Helmer for several of the example gas guns and advertisements.)

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V11N12 (September 2008) |