By Seth R. Nadel

Eugene Stoner is widely known as the designer of “America’s Rifle,” the AR-15/M16/M4, and its original parent, the AR-10. He also created the U.S. Survival AR-7 .22 rifle, which has passed through many hands and is still in production. This is the takedown rifle that fits in its own stock. Then there was his aluminum receiver, extremely lightweight 12-gauge shotgun which was produced for several years but soon left the marketplace. And since there was an AR-7, AR-10 and AR-15, there must have been AR-1s,-2s, and so on, and SAR has covered these numerous times.

While the AR-15 guns were originally chambered in .223/5.56, the AR-10, the original design, was chambered in .308/7.62 NATO. Now the design is available in a raft of calibers, from .22 Long Rifle to .50. It also serves as the base for bolt-action guns all the way up to .50 BMG.

The direct impingement gas system dates to 1900 France, but it was the combination of the gas system, the intelligent use of plastics and aluminum and, most important, the ergonomics, which revolutionized small arms design. The author recently discovered that Stoner’s talents were not limited to rifles. He is credited as the designer of a 25mm autocannon!

The Project

In 1964, Stoner was a consultant to Thompson-Ramo-Wooldridge (TRW), which was working on a 25mm cannon. TRW has a long and storied history. It was started in 1901, after developing a method for making bolts by electrically welding the heads on. TRW moved from that to making parts for cars, then complete aircraft engines, later rocket engines, semi-conductors, satellites and ultimately spacecraft! They evolved into one of the first and largest “aerospace” companies, until they were taken over in 2002. But they also were involved in firearms development and production.

In 1961, TRW received a contract to build 100,000 M14 rifles and another contract the next year for 219,691 rifles. They eventually made 4,874 National Match rifles, which are held to a high standard for accuracy and speak to the quality of the company’s manufacturing abilities.

It was in this time frame—1964 to be exact—that a new project came to TRW, the Vehicle Rapid Fire Weapons System, which became known as the Bushmaster cannon. It was a tight competition, including multiple candidates each from Philco-Ford, General Electric and Oerlikon. The prototypes included a Vulcan type rotary gun, a revolver (single barrel, rotating chambers), traditional single-barrel guns utilizing several different operating systems, even a two-barreled system. The TRW candidate was called the “TRW-6425.”

The competition was somewhat open-ended, as no round was specified, only a result. The intention was to create a vehicle-mounted fully automatic cannon, capable of defeating a lightly armored vehicle at a distance. Guns of 20mm, 25mm and 30mm calibers were contenders. There was already an “interim” gun, and the performance of the new gun had to be better.

Being mounted on a vehicle offers some advantages and some constraints. The gun would have both electrical and hydraulic power available, and weight would be less of a problem than say, in an aircraft. But if you have ever been in an armored vehicle turret, space is very limited, a heavy gun system reduces the ability of the vehicle to carry men and ammo, and the gases from firing must be exhausted from the turret. In the early tanks, crewmen were incapacitated by the fumes from their guns.

The TRW entry prototype only took 22 months from contract to first firing in 1965. Great Britain and France, among other countries, also tested the gun. Various tests and studies went on until 1973, but work at TRW had stopped after Philco-Ford acquired the rights to the design in 1969. Only six of the guns were built. Renamed the PFB-25 (and Oerlikon’s related KB series of cannon), the ammunition was developed by Oerlikon.

(from The Machine Gun, Volume V, by George M. Chinn).

The TRW-6425

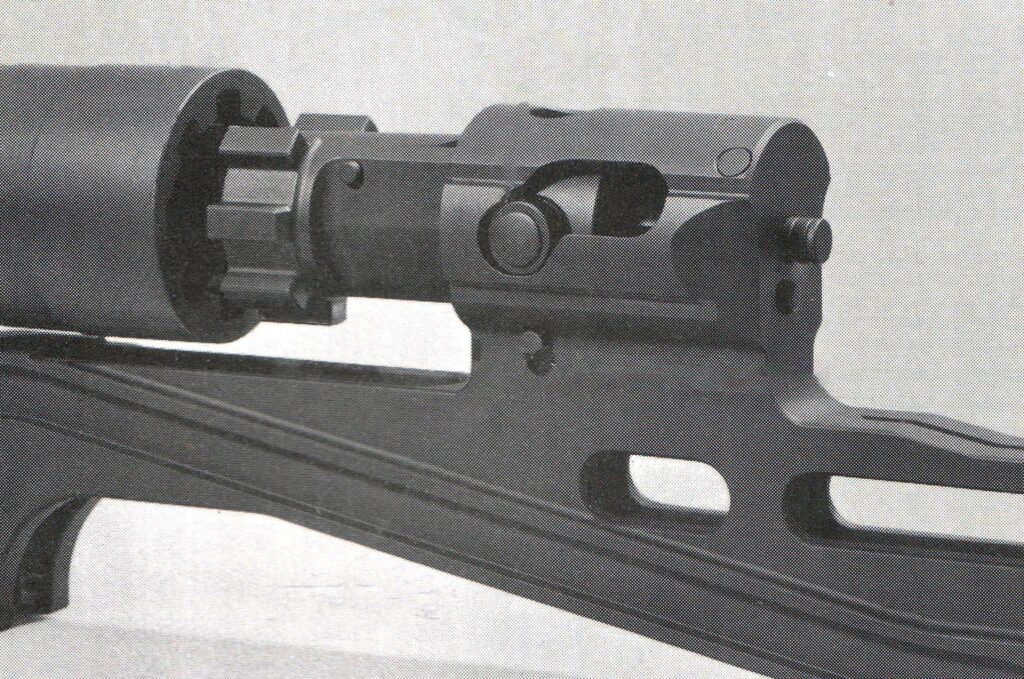

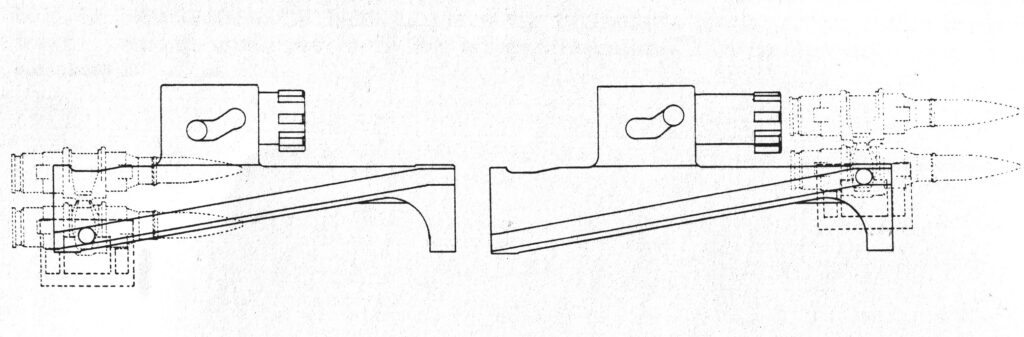

The maximum rate of fire was 550 rounds per minute, with lower rates available, including semiauto fire. It is fed from a belt of linked rounds. Locking of the bolt to the barrel extension was done via the multi-lug system, cammed by a bolt carrier similar to the familiar type in the AR series guns. But there the similarity ends, as the 25mm was recoil-operated. It uses the short-recoil action, where the barrel recoils less than the length of a loaded cartridge. A hydraulic accelerator moves the bolt carrier assembly at 1.5 times the speed of the barrel, providing the impetus for the bolt carrier to cam the bolt out of engagement with the barrel extension. This allows for a short receiver inside the turret.

In the long-recoil system, the bolt remains locked to the barrel until the entire assembly recoils more than the length of a loaded cartridge, then the bolt is held back and the barrel moves forward, extracting the case by pulling the barrel off of it. This requires a very long receiver.

Testing

In short, the TRW-6425 was a failure. There were many malfunctions and lots of part failures. Of course, the idea of testing is to find any weaknesses and see if they can be remedied. Some issues were in fact resolved during testing, and the Ordnance Corps found the gun had military potential but needed further development. Of course, Stoner worked for TRW, and there is no record of him working for Philco-Ford.

It is possible that Philco-Ford was “hedging its bet” by submitting two different guns using two different operating systems into the competition. Certainly having Stoner‘s name associated with the gun would not have hurt.

Ultimately, the Hughes 25mm M242 chain gun was selected for the Bradley Infantry Fighting vehicle. It weighs 230 pounds and can fire 100 or 200 rounds per minute. The same gun in 30mm was adopted as the M230E1 for use in attack helicopters. Both guns are externally powered electrically and operate using an “endless chain” (allegedly designed from a bicycle chain), hence the name. The use of electric power means a shorter receiver inside the turret and less problems with the gasses produced entering the confined space of the turret. It also means a failure to fire (dud round) does NOT stop operation of the gun. The dud round is ejected along with the empty cases, and the cannon continues to fire.

Had TRW kept the rights to the project, Stoner may have perfected it, but history is full of “could haves,” “would haves,” and “should haves.” Eugene Stoner will always be secure in his place among gun designers for his work on “America’s Rifle,” the AR series. The TRW-6425 gets placed with other designs by Stoner—and every other inventor—as one that just missed the niche. Sources: The Machine Gun, Volume V, by George M. Chinn; U.S. Rifle M14—from John Garand to the M21, by R. Blake Stevens.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V24N9 (November 2020) |