A small selection of rifle and pistol reloading powders.

By Seth R. Nadel

This is a follow-on to Seth Nadel’s preceding article titled, “Reloading Ammo—Cost-Effective, Efficient, Fun” in Small Arms Review, Vol. 24, No. 8.

Before you can select a powder, you must know what you want to do (hunting, casual shooting, practice for personal defense or target shooting), what cartridge you are loading, what bullet weight you want to use and your ultimate goal, be it precision, velocity or purely cost savings.

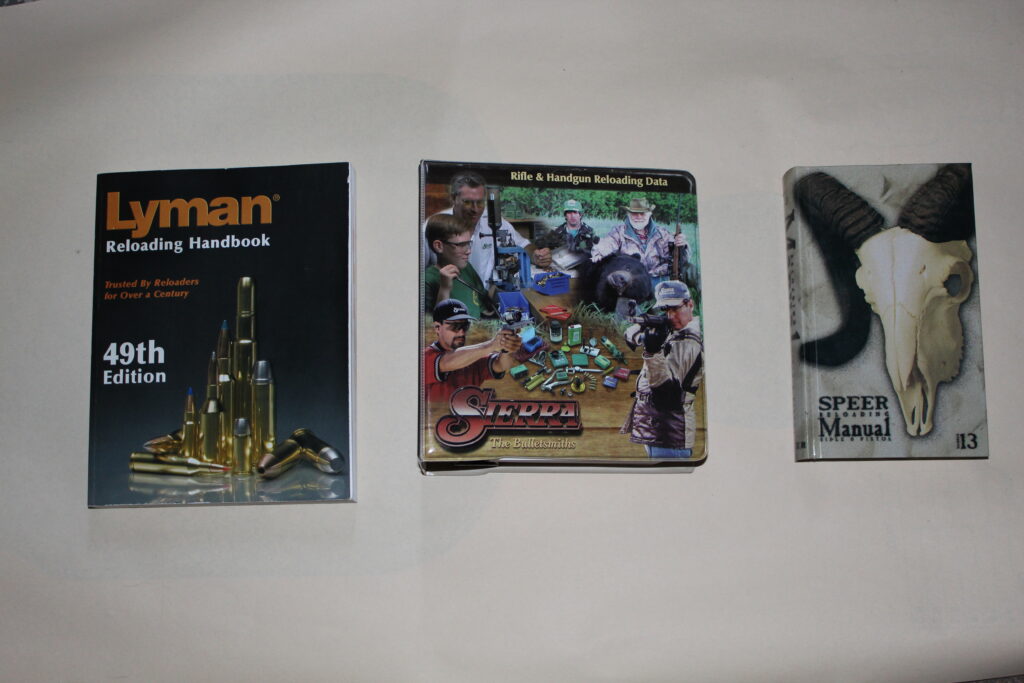

There are many different makes and distinct powders, which are divided into three groups: black powder (and its substitutes), rifle powders and pistol/shotgun powders— in this case, the same powders can be used for both. A visit to a local gun shop showed they carry four types of black powder substitutes and 71 different kinds of smokeless powder for rifles, pistols and shotguns.

We can dispense with black powder, as it is only used in muzzleloading firearms and old cartridges. When the round is known by two or three sets of numbers, such as the 45-70 or 45-70-405, it is usually a round that was created in the black powder era. In this case, it is a .45-caliber bullet, loaded over 70 grains of black powder and weighing 405 grains. The most common round like this is the 30-30, a .30-caliber bullet originally loaded over 30 grains of black powder. There are of course exceptions, such as the 30-06—the .30-caliber round modified in 1906. Black powder is an explosive, with regulations as to how it is to be stored and limits to the quantity of how much a store can have on hand. The substitutes are not restricted.

Smokeless powder is a propellant and much safer to handle. It can be single or double base (nitrocellulose and nitroglycerin) and shaped as rods, flakes or balls. It can be coated with deterrent coatings to change its burn characteristics. You will find “burn rate charts,” which give the relative “speed” at which powders burn. Never use load data for one powder with any other powder, even one from a different maker with the same name, or adjacent on a burn chart.

Smokeless is just that—it smokes less than black powder. It is not completely smoke-free. It is a fire hazard (so no smoking while reloading) but not an explosive hazard. Powder is measured by weight, but dispensed by volume. What does that mean?? The charge—the amount of powder to be placed in the case—is defined by weight in grains and tenths of a grain. Thus you will need a powder scale to weigh the charge. But for convenience it is run through a powder measure, with an adjustable cavity. You set the cavity to “drop” the right amount of powder for each case by weight—the scale lets you set the measure.

Some makers name their powders—Bull’s-eye (the oldest name still in use) is a pistol powder usually used for target shooting at round, bulls-eye targets with pistols. Other companies use numbers: IMR 4895 is “Improved Military Rifle formula #4895.”

Bullets

The bullet is what “does the work,” be it punching a hole in a paper target, ringing some steel, dropping the animal you are hunting or protecting your life. There are a variety of bullets optimized for each use.

The least expensive are lead bullets, cast or swaged into shape for your caliber. These are mostly used for practice and some types of precision competitions. They are limited by the soft nature of lead to lower velocities.

Plated bullets are the (relative) “new kids on the block,” electrically plated with a thin “skin” of copper over the lead. Slightly more expensive than lead, they can be pushed to higher velocities and leave less residue in the barrel of your gun.

The top of the list are the jacketed bullets, where the lead is forced into a copper jacket. These can be sent downrange at the highest velocities—close to 4,000 feet per second in some rifles.

There are a limited number of pure copper bullets used for hunting and a few defensive pistol rounds. Usually found in factory ammunition, a few have found their way onto gun shop shelves.

In addition to their composition, the shape of the bullet is also a factor in selection. For precision pistol shooting in handguns, there are the wadcutter and semi-wadcutter shapes of lead bullets. The wadcutter is used in revolvers and looks like a cylinder of lead, dead flat on the ends. They cut a hole of bore size in the paper target and leave little wads of paper on the ground behind the target—like a hole punch dumped on the ground—thus the name. The semi-wadcutter does the same thing for use in semi-automatic pistols, with a smaller than bore-size tapered cylinder on the top to allow feeding.

Round nose bullets are just that—fine for some kinds of competition and all kinds of practice. Jacketed Hollow points and, for rifles, jacketed soft points, are the choice for personal protection and hunting. Match bullets are, as you would expect, used for competitions—matches. They are made to a high level of precision and, of course, cost more.

Tools

The list is fairly short, and used, err … “previously enjoyed,” tools can be found at discount prices. The author has been using some of the same tools for 50 years while loading an average of 10,000 rounds per year, and in examining used tools has yet to find any junk. All the makers are dedicated to making tools that will last several lifetimes.

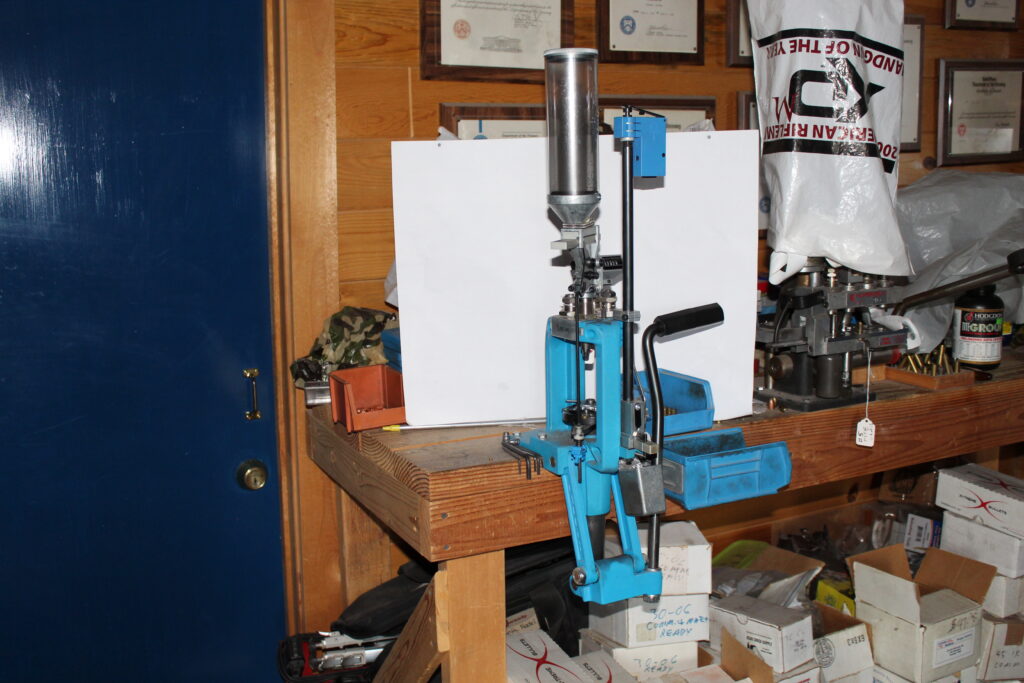

The Number 1 tool is the reloading press. These come in single-stage (one operation at a time), turret (capable of performing each operation on a single case) and progressive tools, which, once loaded with cases, primers, powder and bullets, produce a loaded round with each pull of the handle. For clarity, and because most folks people start out this way, I’ll describe the operations as if loaded on a single station press.

Die sets for each caliber (along with a shell holder) allow you to load different rounds in the same press. With one very minor exception, all dies use the same thread pattern and fit in all presses. For bottleneck rounds, there are two dies in the box. Straight wall cases (rifle and pistol) require a three-die set, as you will see. Dies come in standard, small base, tungsten carbide (for very high volume reloading) and match (higher precision) types.

A case cleaner—rotating, vibrating or ultrasonic is a must have, as is a case trimmer and a micrometer. One final tool is a bullet puller, to “erase” any mistakes.

As noted above, you will need a powder scale and a powder measure. There are lots of small items like boxes, bags, markers, etc., that are not reloading-specific.

Putting It All Together

The first thing you will learn here is there are always two or more ways for each step in turning your brass into ammunition. I’ll cover the most common methods.

We will use the cleaned brass mentioned in “Reloading Ammo—Cost-Effective, Efficient, Fun” (Small Arms Review, Vol. 24, No. 8). Get your dies for the caliber out, and set them according to the instructions. This is a step you only need do once.

The clean brass needs to be lubricated for sizing—reforming the expanded case to its original shape. You can use a pad (which does a fine job of lubricating your hand) or spray lube. If you are loading straight-wall pistol cases and have carbide dies, you can skip lubrication. If you are loading a bottleneck case, even with carbide dies, you still must lubricate. If you fail to lubricate, you will get a case stuck in the die, which is FAR more trouble than lubricating the cases.

With the correct shell holder in place, running the ram to the top (by lowering the press handle) will decap (remove the primer) and resize the case. You can re-prime the case on the down stroke of the ram or choose a separate priming tool. On a bottleneck case, the decapping stem will also bell (expand) the case mouth to accept the new bullet. On straight wall cases this is a separate operation utilizing the second die in a three-die set.

Those bottleneck cases need to be measured for length, as the cases stretch with each firing. The forward portion of the chamber is designed for the diameter of the bullet, not the diameter plus the case wall thickness. This will cause a pressure spike big enough to possibly blow up your gun. Your reloading manual will have the case “OAL” (overall length), and you will need a case trimmer to cut it back. The straight wall cases can skip the trimming as they have no shoulder for the gases to push forward.

By now you have selected the bullet weight and design, and by consulting the loading manual, a powder and charge weight. That charge can be high or low, with two caveats:

1) Never load a charge you “found on the net” unless you can find it listed in a reloading manual or on the powder or bullet makers’ website. Someone’s “perfect load” can work in his gun but blow yours up. Plus you run the risk that it came from some 12-year-old in mommy’s basement who thinks it would be “funny” for you to destroy your gun and possibly get hurt.

2) Use at least two separate sources—two manuals or a manual and one of the aforementioned websites to confirm that the load is safe. Even the folks who write the manuals can make a mistake.

The author always loads “in the middle” of the charges listed. That way if he makes a minor error—the case chosen has an unusually thick side wall, the bullet is a bit on the heavy side or any one of a hundred things beyond his control—he still has a safe load. If the “middle” load is too slow for your needs, buy a bigger caliber gun! If the .308 is too slow, buy a .300 Win Magnum. In the long run, it is much cheaper than pushing the envelope and getting a ride to the emergency room. There is no reason to risk blowing up your gun and/or getting injured in a “pressure excursion” just to get your bullet to go 100 feet per second faster.

After selecting a charge weight, close the manual, reopen it and make sure you are on the right page for the round you are loading and looking at the right bullet weight. These extra seconds can save you from making up an over or under pressure batch! Then using the powder scale and the powder measure, set the measure to drop the correct weight. As another safety check, never accept the first correct weight. Always drop several more charges and then weigh another, as some powders settle and become denser from the operation of the measure. When you first start, weigh every charge. If they are all good, you can weigh every fifth charge and then every tenth as you become more comfortable. Once you establish a consistent rhythm, it’s easy to drop the charges with confidence. You will want a cartridge tray to place the rounds with powder in them and reduce the chance of knocking them over. Only cases with powder in them stand up on the author’s bench, or else there is a chance of seating a bullet into a case with no powder!

Using the bullet seating die, set per the directions, seat the first bullet and let the die crimp the case into the bullet. This keeps the bullet from setting back or moving forward—setting back can drastically raise the pressure, and moving forward can jam a revolver. Then take that first round and make sure it will fit into your magazine. You may want to make up a dummy round (no primer or powder) for this step. Save that dummy, as it can be handy if you ever need to rest your dies.

The final steps are wiping the lube off the completed rounds, if you have not already done so after sizing, and then boxing or bagging them with the load data. You’ll want the caliber, case make, powder make and charge, and bullet make and weight on a note with your handcrafted ammo.

Going Forward

Once you become confident, you may want to experiment with higher or lower powder charges or different bullets and seating depths. You can customize your loads for the best precision in your rifle or pistol or produce large quantities for the same cost as store-bought ammo. You may also decide shooting your ammo is so much fun that you want to shoot more and perhaps move up to a progressive press. With such a tool, you pre-load it with powder and primers, then put in a case and a bullet, pull the handle, and a loaded round comes out!

So start saving your brass and try reloading it!

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V24N10 (December 2020) |