By Frank Iannamico

This article is the first in a series based on the memoirs of Burton “Bob” Brenner, a man who was one of the early pioneers of the military surplus gun trade in the United States. The series will tell of his adventures and business ventures over the span of his interesting career, to include arms caches and deals that will bring a tear to your eye. To most readers, Mr. Brenner’s life would be a dream come true, traveling all over the world seeking, and finding, unmolested treasures in military small arms, many forgotten, others abandoned by conquered armies, but all having a unique history and an untold story.

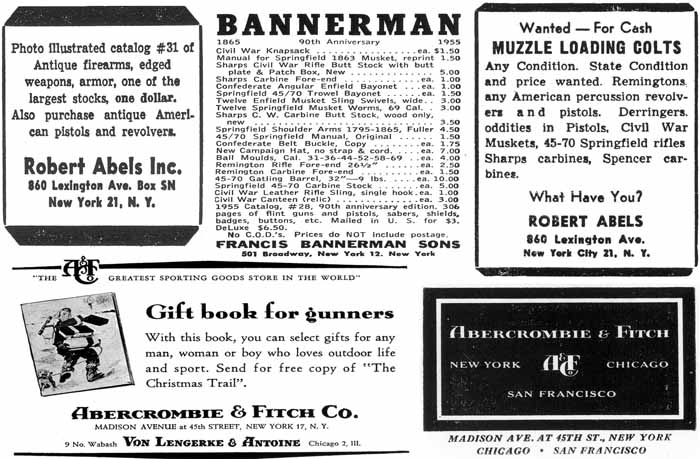

While doing additional research for this series, some ads from old Shot Gun News issues from the early 1960s and many 1950s era American Rifleman magazines were found. It was a nostalgia trip back to a more innocent and gun-friendly time. An interesting observation was that most all of the major dealers of the day were located in large cities like New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Washington DC; all adamantly anti-gun today. Similarly, the NRA annual meetings were held in many of the aforementioned locations. In light of today’s anti-gun climate, it certainly makes one wonder what happened.

The Origins of Gun Collecting

The earliest manifestations of gun collecting seem to have arisen from Europe where weapons were presented to royalty – magnificent masterpieces of pistols and shoulder arms traded from one imperial house to another. Few of these exalted specimens ever fired a single shot and were diligently cared for by qualified attendants, therefore surviving for centuries unmarred.

During the 19th century in Europe, a rising class of wealthy traders and industrialists altered the former convention of which fine arms were only passed between the highest echelons of the rich and privileged. Capable of commissioning their own craftsman, or perhaps prevailing on a financially embarrassed lower lord to part with an heirloom, these new collectors had risen from the ranks of nouveau rich entrepreneurs and became interested in amassing arms collections.

This arms collecting phenomenon was not as evident in the United States, where the rustic demands of the ever-moving frontier consumed all time and effort. Similarly the gathering of essentially utilitarian objects into a collection devoted to gratifying a personal need, or serving the public appetite for viewing a collection of firearms did not appear to suit Americans of the period.

The American Civil War can be viewed as a turning point in U.S. gun collecting. In its haste to arm Union troops the federal government awarded a number of contracts for untried weapons and equipment. As a result many of these military arms and equipment became obsolete in a short period of time and became available to the masses at very low prices. The weapons included many innovative (if ultimately unsuccessful) designs of the day that were offered to the public by merchants such as New York’s Francis Bannerman and H.K. White. This new wave of surplus was not limited to guns, but included edged weapons, military accouterments, and basic items such as tents and canteens, which were eagerly purchased by outdoorsmen, hunters, frontiersman, and the throngs of individuals that were heading west.

In addition to those who purchased surplus goods to support their existence, many customers during that gun-friendly era were simply interested in American history, as are many modern collectors. While most Americans of the period could never conceive of owning richly engraved and inlaid with precious metals created by royal craftsmen, the average American could easily afford and obtain government surplus guns for the pleasure, and not necessarily the need, of having them.

After the Civil War, the next wave of surplus, and next stage in the chronicles of U.S. gun collecting, occurred in the wake of the Spanish-American War, as the recently adopted Krag-Jorgensen rifle of Norwegian origin gave way to the more modern Model 1903 Springfield rifle. The American collector now had available colonial flintlock muskets from the revolutionary period, flintlocks and caplocks from western pioneers, arms used by both cowboys and Indians, arms from the Civil War, and the Spanish-American War. However, the greatest surge in arms collecting the world had ever seen would occur at the end of World War II.

Burton “Bob” Brenner

Burton Brenner was born in the Bronx and raised in Manhattan, New York, which today seems an unlikely beginning for such a story. As a young boy growing up in the 1930s his family struggled through the depression years. His father had a medical supply business that managed to survive, and young Burton was expected to eventually follow his father into the business. During World War II, Burton was in high school and upon graduating was looking forward to joining the U.S. Army Air Corps as a pilot or gunner. During 1943 as a high school student his daily route to school took him past an antique shop that had an old musket and saber displayed in the window. One day he decided to stop in and look around and found the shop filled with old guns.

Robert Abels, Inc.

The store itself was an experience, a dream, a collector’s Valhalla located at 860 Lexington Avenue. The first room, about eighteen by fourteen feet, was completely jammed with guns. The walls were lined with rifle racks, and the floor was filled with freestanding circular racks, all filled with long guns of every description. The room held around a thousand guns as well as a couple of huge armoires containing odds and ends such as helmets and flags.

A middle room contained several showcases, which like the rifle racks in front, were jammed into the room as tight as possible. The room also held safes and cabinets, including an oak legal cabinet filled with old revolvers. The drawers of all the cabinets held antique sidearms of every type. The back room had a small workshop and, naturally, more storage area.

The shop owner was Bob Abels and Burton would work at the shop for the next four years. Mr. Abels would become a mentor and friend to Burton Brenner and help to define his destiny. Young Burton’s first assignment at the shop was to sweep the floor and clean the glass on the showcases. Before long his duties were expanded to cleaning and oiling guns, and eventually helping in obtaining guns for the shop to sell.

Abels received all the catalogs from the various auction houses and would pore over them for possible purchases. He would assign to Brenner the task of going to these auction houses and looking over the material that he was particularly interested in. Many times he was allowed to actually go to the auctions and do the bidding. Often as not, Abels would simply do his bidding via the telephone.

During the spring of 1945 the war in Europe was finally coming to an end and many U.S. troops were anxious to get home and get on with their lives. Most of the returning servicemen from the European Theatre came back to the United States on large ships like the Queen Mary and the point of debarkation was New York Harbor. An average ship returned around 40,000 men at one time, most all of them carrying souvenirs from the war.

Sensing a unique business opportunity Mr. Abels placed advertising boards down at the docks and hired men to wear “sandwich boards” to stroll around the city. In effect, all the ads stated, “Why drag all of that junk home? If you need money, this is the place to get it”.

As Burton walked to the shop the first day after the ads appeared, he saw an endless line of servicemen that took up an entire city block on Lexington Avenue and around the corner over to Park Avenue, all with souvenirs of every description in hand. The buying commenced at 7:30 a.m. and continued on until 7:00 p.m. on the first day. This was repeated for many weeks as the big ships sailed into New York from Europe with more and more servicemen, all with souvenirs to sell.

Among the flags and medals were the guns. Many, like the German P-38 pistols, had never been seen in the states before. Others handguns included countless Sauers, Broomhandles, Browning P-35s, Radoms, Mausers and a least 1,000 Luger pistols. An average price paid for a decent Luger during this period was $10. Mr. Abels would then sell the piece for $35 fetching a nice profit for the times making him a substantial amount of money.

The Famous Bannermans and Others

As young Burton Brenner continued to work and learn at Bob Abels’ New York shop, he made many new friends and acquaintances among the diverse customers that came into the store. Of course the talk always was about firearms, of which Brenner was eager to learn and asked many questions. Through the course of these casual conversations he soon learned of the legendary Francis Bannerman’s, a large gun shop also located in New York City. Bannerman’s was one of the first of many businesses established in the United States that would become known as Army-Navy stores. Bannerman’s was among the largest and most unique firearms business ever established in the United States.

Bannerman Island

Francis Bannerman, a Scottish immigrant, had established the famous Bannerman’s business in 1865. As the U.S. Civil War ended, the elder Bannerman began to buy up military belt buckles that had been made by the millions for the Union army. The buckles consisted of a brass outer shell with a solid lead backing. Mr. Bannerman had spent several years melting the lead out of the belt buckles and selling it as scrap metal. Bannerman had three sons; Francis VI and David Boyce eventually took the business over from their father and expanded it to include surplus armament from around the world. Needing additional storage space for their ever-increasing inventory, Francis Bannerman VI purchased the 6.5-acre Pollepel Island on the Hudson River for future use as a storage facility.

After the Spanish-American War ended, the Bannermans purchased over ninety-percent of the remaining U.S. army surplus from the conflict, including a large quantity of rifle cartridges. Because his storeroom in the city was not large enough to contain his inventory, which now included large lots of ammunition, he began to build a storage facility on Pollepel Island, now known as Bannerman Island. Most of the buildings were used for the storage of the business’ surplus. During August of 1920, a fire, fed by the large stores of ammunition exploded in one of the storage buildings, destroying a portion of the complex. Bannerman’s Castle island facility was only accessible by boat, which was served by the ferryboat Pollepel that was sunk during a storm in 1950 and soon after the facility was abandoned.

The White Brothers

Another New York surplus store young Brenner learned of was the White Brothers who were a former competitor of Francis Bannerman during the post Civil War era. The White Brother’s business was located in Lower Manhattan near Pearl Street in a small unassuming building amidst incredible skyscrapers. The White family still owned the building and the business was run by their two sons who at this time were in their 70s.

White’s had a substantially smaller inventory than Bannermans, but everything that they had was in brand new condition. The founder of the organization had apparently specialized in purchasing unissued surplus. Just one example of their inventory were 1842 muskets. The weapons were brand new, still in their original crates, and stacked to the ceiling of the White Brother’s back room. They were priced at $37 each.

Abercrombie & Fitch

Another famous establishment located in Manhattan, New York City was Abercrombie & Fitch, who catered to upscale clientele. At one time, the famous Abercrombie & Fitch emporium in Manhattan, which catered to wealthy outdoorsmen, hunters and the like, carried a stunning array of hunting rifles and shotguns. Their gunsmith factory was located in a nearby building. The men employed there were true craftsmen working in gold and fine woodworking. Brenner was given a tour through the entire factory where they were building custom hunting rifles from surplus Mauser and M1903 Springfield actions.

Gimbels Department Store

Gimbels, a famous department store and a name that is not normally associated with firearms, ran advertisements in the New York newspapers offering fine antique swords and rifles. At their New York store there were hundreds of swords, pistols, rifles, and daggers all imported from North Africa. Everything had been priced ridiculously low. It was later discovered that all the material being offered at Gimbels had originally been owned by Mr. William Randolph Hearst. He had shipped the goods from Africa to New York, but something was suspect with the paperwork regarding ownership, and all of the items eventually were sold at an auction held by Customs. The entire lot was subsequently purchased by Gimbels Department Store.

Numerous other smaller gun shops were located in New York behind the old City Police Department building; most of these establishments were run by Italians. One such company was called Sile’s. Brenner did a substantial amount of business with this company during his early years. Back in Italy the company was a large manufacturer of wooden rifle stocks.

With all of the early activity in the New York gun and surplus trade, today there is not a single established gun dealer remaining in New York City.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V12N2 (November 2008) |