By Frank Iannamico

Martin Retting

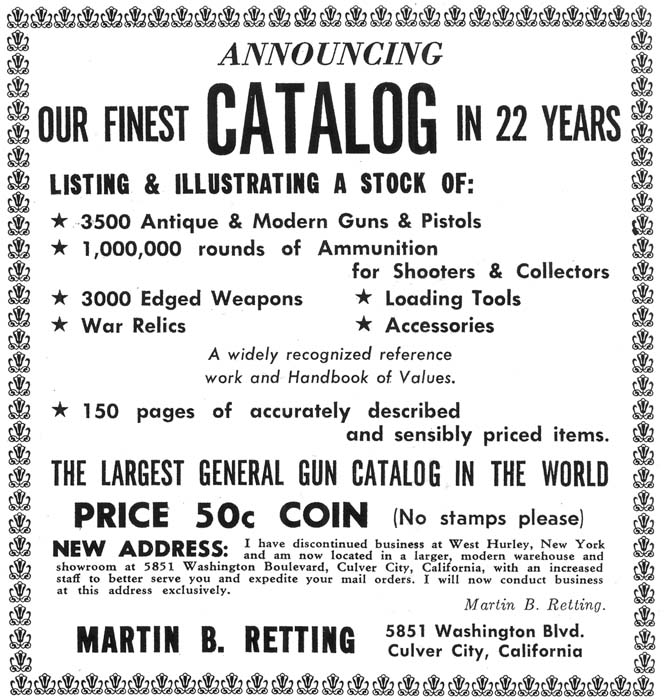

Burton Brenner met and came to know a fellow by the name of Martin Retting, who was a mail order gun dealer operating out of an old barn up in West Hurley, New York about 90 miles from New York City. Martin used to drop by Bob Abels’ shop every so often and buy or trade and before long Brenner and Martin became friends.

Eventually the time came when Brenner felt that he wanted to move on from Bob Abels’ store. Martin offered him an attractive proposition. Retting had realized that his business was growing too fast for him to efficiently handle it by himself and he was looking for somebody to take in as a potential partner. Brenner seized the opportunity and went to work for Martin Retting.

With his flair for drawing, which Brenner had honed while working for Bob Abels, Brenner was able to put out catalogs for Martin with increasing proficiency. As it became increasingly clear to Martin that Brenner was more than capable at running many parts of his business, he decided to pursue the many inquiries from Europe that were coming in. There were letters from gun dealers in England and Belgium, which Martin thought were worth looking into and he decided to go to Europe and take advantage of Brenner’s obvious ability to run things at home.

The European Trip

During Retting’s European visit he met many dealers in both countries where he was able to purchase a significant quantity of material. Belgium was of particular interest as he found a company very similar to Bannerman’s. They had stacks of surplus weapons from the war of 1812. Much of this weaponry was from the American Revolutionary War, which had been sold off as surplus to the French. There were also stacks of U.S. 1795 Springfield Muskets, which had been modified by the French to suit their needs. Martin was able to negotiate a price that enabled him to just about clean out the entire inventory of the Belgium company. From Belgium Retting traveled to England where he was able to purchase a substantial quantity of U.S. M1903 Springfield Rifles.

The Swiss Deal

Martin had also gone to Switzerland where, with a letter of introduction to Peter Anniston who had excellent connections within the Swiss government, he was presented to a Swiss military commander in Geneva. The man was assigned the duty disposing of obsolete materiel and the commander welcomed Martin and soon agreed on terms for disposal of his unwanted goods. This cache of weapons, as it turned out, represented a find of literally historical proportions.

Most of the items were originally from France, for the soldiers of that land originated a practice known as “French leave.” Summoned into action at any point within a march of the Swiss nation, the reluctant Gallic troops would march over the Franco-Swiss border and surrender to the authorities. The Frenchmen would then be interned for the duration of the conflict between France and Germany, or France and Belgium, or France and Spain, or whomever France was fighting at the time.

First the Swiss would disarm the French soldier. His military equipment, including swords, body armor, helmets, saddlery, and of course guns, would be taken and stored in the depot on Lake Geneva. By this process over many decades, the store of these spoils came to resemble geological strata, the oldest pieces at the bottom, the newest at the top, and everything between in chronological order, dating back to the Napoleonic wars.

This was a find of large significance. At that time, just entering the mid-1950s, practically nothing in this type of trade had come out of Europe in many years. Little was known about most of the French arms, equipment, and accessories that were piled in this depot which were filled with the most exotic of items.

The expeditions of Napoleon yielded to Martin Retting hundreds of sabers; an important part of the French military’s armament. There were light sabers, medium sabers, heavy sabers to go along with the corresponding light, medium, and heavy cavalry. All were in superb condition, having been maintained very nicely by the Swiss.

The next layer of material proved to be that of the Franco-Prussian war. This was a thin slice of the total, as that conflict did not last very long: breaking out in July of 1870 and ending in May of 1871. Retting did get from the remains of this rather brief military adventure a batch of primitive bolt-action Gras rifles and other items of that time period. This was enough to create quite a stir among collectors once it was finally catalogued and offered stateside.

The World War I stratum was a much more generous source of supply, given its longer span and the multitudes of fighting men involved in it. This period in history produced for Retting and Brenner crate after crate of Lebel and Mannlicher rifles, all in fine shape and complete with needle bayonets. Of even greater interest was a cache of semiautomatic rifles, including the French models of 1917 and 1918. These were among the first successful semiautomatic rifles used in Europe and they were infantry weapons, not light machine guns, and thus capable of deployment with ordinary foot soldiers. The 1917 model was a long affair, about like its antecedent, the full-length infantry Lebel. But the 1918 version was a fair bit shorter, and was in effect the assault rifle of its day.

No one in the States had previously seen the Model 1918 rifle (except, perhaps, in the trenches), and the few dozen in the shipment were immediately snapped up by collectors. It is probably the only lot ever imported. These, rounded out by thousands of helmets, individual leather gear, belts, buckles, insignia, and the like, amounted to an imposing treasure of World Way I history.

The next layer, again larger than the last one, contained the latest items of World War II when, as before, the French soldiers made it over the Swiss line to suffer capture and ride out the war. The Swiss authorities confiscated many bolt-action MAS rifles, which was then an extremely rare weapon.

Along with the MAS rifles came the entire range of French ordnance revolvers in both 8mm and 11mm. There were plenty of semiautomatic pistols used by the French; basic blowback mechanisms in .32 and .380 caliber, and there were thousands of them.

After Martin’s return from Europe, Brenner took a trip to look for more material in the Midwest part of the U.S.

At that time, Martin did not have very much military surplus in his inventory. He did procure a few hundred of M1903 Springfield rifles from England, which sold very well and gave him a taste for what this sector of the market might hold. The Springfields were followed by a deal involving a quantity of Schmidt Rubin rifles, and then finally by the big Swiss deal which had brought them so much plunder of the Napoleonic era wars. Other than these few foreign deals, most of their stock was obtained by over the counter trading, with local people bringing in firearms of all sorts, to see what they would bring. These deals brought into Retting’s a substantial variety of weapons that was readily sold to eager collectors.

In working upstate with Martin over the next couple of years, Brenner did a lot of traveling to some of the really interesting gun collector groups, particularly the Ohio Gun Collectors Association. They would meet in a different Ohio city every month, and Brenner attended may of these gatherings. There Brenner met or reacquainted himself with some of the greatest collectors in the country, many of whom Brenner first met at the Abels’ shop. Bill Locke had an incredible Colt collection. Pepperboxes were the specialty of Bill Smith who had an endless store of American weaponry. Bob Rubendunst brought together a vast military rifle collection, probably the most incredible outside of military and civilian museums. John Amber, who was just beginning his editorship with Gun Digest, would also show up. John attended many of these meetings, and they got to be great friends. Brenner helped a lot of these fellows get the particular pieces they were looking for, and the association meetings were marvelously educational and enjoyable. They were early-day gun shows, with a select group of members who know what they were talking about. Trading was fluid, and very nice guns were thus made available. It was a remarkable era in gun collecting.

The Move to California

At about this time (1953), Martin Retting made the decision to move out to California. His parents had already moved there, and Martin had visited and liked it. He asked Brenner if he would be willing to relocate there with him. Brenner was no more than twenty-four years of age then, and the idea of California was alluring, so Brenner readily agreed to make the jump with him. The men spent three weeks loading up four big trucks with his entire inventory of merchandise, parts, machine tools and such, and away they went.

Brenner had bought himself a nice Pontiac, and in it made his first trip across country by car. Brenner had gone about half the distance many times before, but this time it was all the way. Two old friends of his, which were hired just for the loading and unloading of the trucks on this trip, drove along with him, all having the adventure of their young lives. Imagine three young guys, money in their pockets, rolling down Route 66 west through vast stretches of country before the days of the interstate highways, the desert landscape dotted with concrete Indian teepee motel rooms. They finally reached the outskirts of Los Angeles well after sundown, but kept going until they hit the beach. They all stretched out on the sand and slept under the stars that first night in California.

The next morning, stiff, cold, and gritty from their seaside beds, they found their way to Culver City where Martin had previously found a building to house the business. After a few days of unloading and setting things up, they opened the doors for business, and almost immediately realized they had hit the jackpot. The city was bursting with new arrivals from all over the country like themselves, and it was ripe for a first-class gun merchant who dealt in all sorts of new and interesting merchandise. Right from the start, they did an incredible amount of retail business. The experience from their New York days was really no comparison, as their sales had previously been largely to other dealers and serious collectors, not the guy walking in off the street. Still, it was clear from the outset that they would be doing an extremely substantial volume in surplus arms from all over the world. There seemed to be a never-ending demand for this material.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V12N3 (December 2008) |