By Robert Bruce

Part One: Developmental History and Combat Use from WWII to Vietnam

Affectionately known to generations of American Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen and Marines as “Ma Deuce,” John Moses Browning’s .50 caliber machine gun entered U.S. service in 1921 and is still going strong. Although too heavy for most bootbourne infantry operations, the big, bad M2’s devastating firepower, extreme range and legendary reliability under the worst conditions make it a favorite for ground defensive positions, vehicle, aircraft, and antiaircraft mountings. Now, at the ripe old age of 78, “Grandma Deuce” is still kicking butt worldwide and is likely to remain in first line American military service well into the 21st century. Go Granny, Go!

Introduction

In this, the first of two installments, we will examine the circumstances leading to John Browning’s development of his extraordinary .50 caliber heavy machine gun during World War One. Then, we will follow its refinement and evolution into a versatile and highly capable system including the watercooled and aircooled versions that played a key role in winning World War Two. Part one concludes with a brief look at “Ma Deuce” in Korea and Vietnam.

The Great War

Browning’s big fifty was developed in urgent response to some remarkable technological advances during World War One. “The Great War,” as it was known at the time, began in 1914 and soon mired down into parallel trench lines stretching hundreds of miles across Western Europe. In the four unimaginably horrible years following, increasingly sophisticated bomber and fighter aircraft of both sides flew high above the miserable and filthy infantry. Well beyond the range of rifle caliber machineguns and poorly aimed AA cannon fire, these airborne raiders rained havoc on the trenches and on support and supply activities in rear areas. Early on, the clever and industrious Germans adapted their Zeppelin dirigible airships into floating fortresses and began nightly bombing attacks on the allied capital cities of Paris and London. These torpedo shaped armored dreadnoughts of the sky were so heavily equipped with machine guns that allied pursuit fighters had virtually no chance of shooting them down. Many valiant French and British fighter pilots whose own rifle caliber guns with ordinary bullets proved no match for concentrated firepower from the “beastly Hun”, spiraled down thousands of feet in flaming coffins.

Observation balloons, actually an innovation of the American Civil War of the 1860’s, were also used by both sides. Tethered a couple of miles behind the front lines, they lifted artillery forward observers to vantage points high above the battlefield, giving them the ability to direct murderous barrages with pinpoint accuracy. Out of range of most ground based guns and always well protected by large numbers of antiaircraft machineguns and cannon, these stationary gasbags taunted their victims while remaining largely immune to retaliation.

But the German’s had an achilles heel in both their Zeppelins and observation balloons. Highly flammable hydrogen gas was the lifting agent and once ignited by even the smallest spark, they would be almost instantly engulfed in flames. But, how to deliver that fatal spark at a great and comparatively safe distance?

The French were the first with a partial remedy, hastily fielded in early 1917. Made with practical expediency by beefing up the 8mm Mle 1914 Hotchkiss guns to handle an 11mm incendiary cartridge of somewhat increased range, it soon became known as the “Balloon Gun.” The British immediately followed suit by adapting their highly efficient Vickers gun — mounted in pairs on fighter planes and synchronized to fire through the spinning propeller —to fire this acceptably effective incendiary cartridge. The tables were turned and now German Zeppelin crews and balloon observers were the ones plunging to a fiery death.

Despite its immediate success, the 11mm “balloon gun” round was still not sufficiently powerful for really effective long range antiaircraft work. But, while allied experimentation continued, it was the Germans who were now most anxious to have a bigger bullet and a way to fire lots of them as fast as possible. This anxiety quickly turned to near panic when the allies gave them yet another nasty surprise.

“Tank und Flieger”

The first large scale battle use of allied tanks in World War One came in April 1917 when ten groups of French tanks spearheaded General Nivelle’s Asine Offensive, reportedly catching the Germans completely unprepared. Although slow and awkward, these lightly armored tractors flattened thickets of barbed wire and lumbered right over shell holes and trenches. Their on board machine guns and small caliber cannon wrecked havoc on well dug in German infantry whose 8mm Maxim gun fire bounced harmlessly off the enemy’s tanks.

Adding to German impotence, supporting artillery was unable to provide effective responsive fire against the creeping pillboxes. Already decimated by years of trench warfare and demoralized by the arrival of fresh American troops, the Kaiser’s army was in danger of total collapse unless a way could be found to deal decisively with this grave new threat.

German ingenuity quickly asserted itself in a formidable 13mm (actually 12.7mm or .50 caliber) cartridge made by the Polte firm. With an amazing muzzle velocity of some 2,700 feet per second, its 800 grain armor piercing bullet could slam right through a full inch of steel plate at 50 yards. An early combat test unmistakably proved its capabilities when a single shot pierced both sides of an unlucky English tank!

The Germans had two plans for launching this big and hot new round with the first being a crash program to design and build the “TuF.” Short for “Tank und Flieger” (tank and aircraft), the TuF was essentially a standard MG08 Maxim gun bulked up double in size. It was intended to deal not only with swarms of allied tanks, but also serve as an aircraft and antiaircraft gun capable of reaching out to great distances to deliver deadly doses of lead poisoning. Since it must have been obvious to all concerned that this complicated gun could not be built soon enough, the tried and true 8mm bolt action Mauser 98 rifle was given similar treatment with steel steroids as a quick fix.

By the spring of 1918 the already miserable lives of Allied tank crews inside their hot, stinking and clumsy machines got immeasurably worse when quantities of the 38 pound 13mm Model 1918 “Tankgewehr” (tank rifle) began to be employed. Despite the new rifle’s deadly close range efficiency, it was not enough to turn the tide of war and Germany surrendered on 11 November 1918, months before the first TuF Maxims could be fielded.

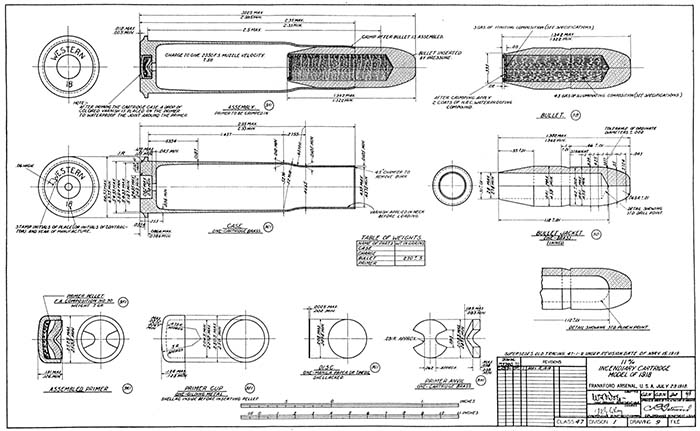

.50 Caliber Cartridge

German development of this powerful rifle and cartridge combo had not gone unnoticed by the allies who soon captured quantities of both. It didn’t take a rocket scientist to realize that the small arms race had been ratcheted up considerably and that French wonder cartridge — the 11mm Hotchkiss “balloon gun” incendiary round — was way behind the power curve.

As luck would have it, none other than John M. Browning himself had already been at work on a “TuF” of his own since July of 1917. Starting with his .30 caliber M1917 machine gun that had just been adopted by the US Army and Marines, Browning settled back in at the Colt factory and began adapting his short recoil, water cooled bullet hose to handle Winchester’s secret new .50 caliber cartridges.

The Ordnance Department had given Winchester what they probably thought was a straightforward contract that summer to scale up the standard .30-06 caliber rifle and machinegun cartridge to .50 caliber. Specifications called for a projectile weight of 800 grains, muzzle velocity of 2,700 fps, and ability to penetrate a minimum of 1.25 inches of armor plate at 25 yards. Colt had their hands full with a contract to build a gun that would weigh no more than 50 pounds yet reliably and accurately shoot this energetic cartridge at 500 to 600 rpm.

Unfortunately for allied forces in Europe both on the ground and in the air, Browning’s work on the bigger gun was hobbled by problems caused when Winchester engineers took unauthorized liberties with their cartridge contract. Not only did they gave it a prominent rim like that of the French “balloon gun” round, its bullet weight and muzzle velocity were inferior to specifications. Worse yet, they were far inferior to test data on the newly captured German Tankgewehr round. General “Black Jack” Pershing, Commander of the American Expeditionary Force in Europe, was not amused; he had seen first hand what the big bolt action Mauser Model 1918 rifle could do to his thin skinned tanks and was not about to accept being outgunned.

A Star is Born

For about a year while all of this was going on Browning’s work went steadily forward. The first firing of a freshly assembled preproduction prototype gun took place on 15 October 1918. John Moses himself personally fired nearly 900 of the rimmed and comparatively puny Winchester .50 caliber cartridges including bursts of up to 150 rounds. This date marks, for all practical purposes, the birthday of “Ma Deuce.”

Although demonstrating mechanical success, these water cooled prototype guns were reportedly quite difficult to control despite weighing a hefty 160 pounds including a particularly robust tripod. These problems were compounded when Winchester finally got back on the right ammo track by not only dropping the old fashioned rimmed case, but by putting into production an almost direct copy of the powerful 13mm Tankgewehr/Tuf round.

In turn, Browning’s immediate efforts went into redesigning the boltface and ammo feed system — back to that of his original M1917 gun which quite handily ingested and fired rimmed .30-06 ammo. The second and certainly most vexing challenge was in reducing the overall weight of his gun while efficiently handling the hot 12.7mm German/ American cartridge with its much greater chamber pressure and recoil impulse.

Although the urgency of fielding this big new machinegun evaporated when Germany surrendered, Browning continued work on his “Fifty.” One obvious external change was tossing out the little M1917 style pistol grip in favor of a two fisted pair of spade grip handles. While this helped with aiming during full auto fire, most of the controllability problems were conquered by his design of a clever oil filled buffer. This served essentially as a hydraulic shock absorber, smoothing out the sharply recoiling bolt.

The oil buffer allowed Browning to significantly reduce the overall weight of both the tripod mount and the receiver — though not anywhere near the Ordnance Department’s physics-defying specification of a fifty pound gun. It also provided the useful option of allowing the gunner to regulate firing speed of the gun to deal with a wide range of tactical situations. This last characteristic would soon prove to be an essential attribute as the basic gun was adapted to many applications on ground, vehicles, boats and planes.

Model 1921

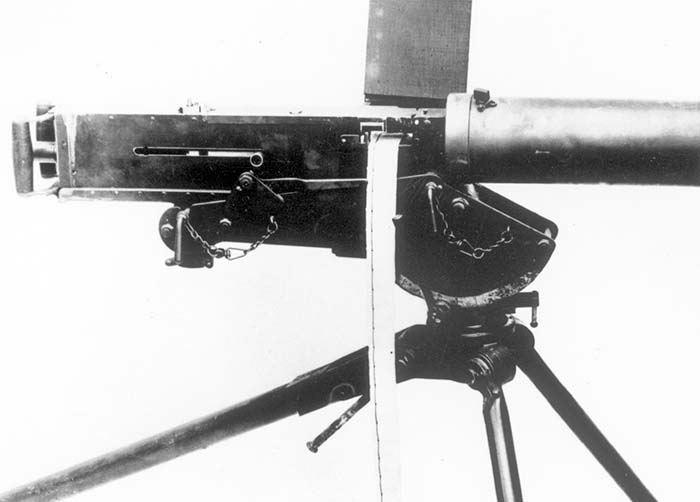

Apparently satisfied with his efforts, Browning returned to his home in Ogden, Utah while Colt’s engineers continued development. Two versions were type classified by the Army as the M1921 Caliber .50; the first a water cooled ground mount gun, and the second with an air cooled barrel for aircraft mounting. Small quantity delivery began in 1925 and, due to postwar “downsizing” of the military and its budget, less than 1000 guns of both types were purchased over the next ten years.

Apparently fascinated by the performance of its powerful new Browning heavy machine guns, the Army undertook a protracted series of experiments and demonstrations with both types of guns in an endless variety of ground and air roles. According to contemporary accounts, this had the practical effect of not only proving the .50 cal’s deadly effectiveness, it also convinced key officers in all branches that many more of these hard-hitting bullet hoses would be needed in the next inevitable war.

Weapon System

The time between wars was also put to good use in continuing refinement of the “Fifty.” While we now take for granted the economy and efficiency of a systems approach to weaponry, many parts for the big gun’s air and ground versions were not readily interchangeable. Under the able direction of former Army Colonel and then Ordnance Dept. engineer S.G. Green, the guns were reworked for common dimensions and adaptability to a standard catalog of various barrels and other components.

One particularly clever innovation was Green’s system for quick conversion to left or right hand feed, facilitating installation in aircraft and multiple gun mounts. Another was beefing up critical parts and reinforcing stress points on the receiver to ensure reliable and continued functioning even under the most abusive sustained combat conditions. Improved ground guns were designated M1921A1 and the aircraft version as M1921E2.

“Ma Deuce”

While water cooling gave the ground gun an amazing capability for sustained fire, its excessive weight and need for expert attention were serious handicaps in infantry and cavalry operations. This was remedied by abandoning the water jacket and fitting a much heavier air cooled barrel that would still allow a volume of fire to meet most combat requirements. After experiments with various diameters and even cooling fins, Colt’s new air cooled ground gun was standardized in 1933 as the Browning Machine Gun, cal. 50 Heavy Barrel, M2, characterized by a gracefully tapered smooth surface 36 inch barrel.

Because the Army’s budget had been devastated by the Great Depression, there was little money to support procurement of the new and improved M2 HB and other .50 cal ground and air models utilizing the same basic M2 receiver. Fortunately the Navy had some money and they stepped in to keep alive further development of the system including refinement of engineering drawings and standardization of manufacturing procedures. By 1940 when it was obvious that America would be compelled to enter what was to become WWII, the whole family of Browning .50 cal guns was ready for mass production by a variety of contractors.

Another World War

The Navy’s paltry $150,000 initial investment paid off big between 1940 and ’45. According to Terry Gander in his indispensable new book BROWNING M2, the mind boggling figure of nearly two million .50 cal Brownings poured out of government arsenals, traditional gunmaking firms, and even hastily converted former automobile parts factories! With very few exceptions, we are told, all of their parts proved fully interchangeable among all M2 series guns regardless of where they were made. This, by itself, is an astonishing accomplishment.

Air cooled M2 “Fifties” in single and multiple mounts served the Navy on its PT boats and in carrier based aircraft, while water cooled M2 guns in dual and quad mounts protected warships from attacking enemy planes. The Army Air Corps used astronomical quantities of the air cooled M2 guns to arm its massive fleets of bombers and fighters. With special lubricants and knowledgeable maintenance, these guns earned an enviable reputation for reliability and effectiveness even in the subzero temperatures of high level bombing runs and the equally hostile salt spray environment of surface ships.

For the land forces of the Army and Marine Corps, John Browning’s heavy machine gun proved its worth beyond a shadow of doubt under the worst imaginable conditions. From the frozen arctic to burning sandswept deserts, from the steaming jungles of the Pacific to the bottomless mud of the Italian campaign, M2 water cooled and M2 heavy barrel guns beat just about anything the enemy had — up to and arguably including 20mm. In ground, antiaircraft and vehicle mountings, Browning’s big Fifties poured a devastating stream of heavy caliber bullets to ranges far in excess of 3000 yards, decisively outperforming German and Japanese rifle caliber machine guns and other readily available weaponry.

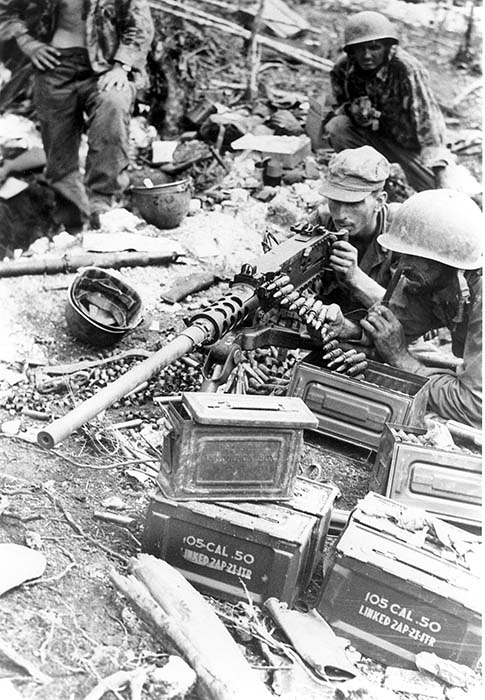

Really Heavy Machinegun

Range and muzzle velocity performance of the .50 cal. M2HB that became the standard WWII production model was considerably improved by fitting it with a 45 inch barrel, standardized in 1938. Many of these early guns were also fitted with an T3/M3 3.25 power prismatic telescopic sight to aid with long range shooting. With its previously mentioned receiver reinforcements and this longer barrel this new M2HB tipped the scales at about 84 pounds, and its sturdy M3 tripod added about 44 lbs more. This gives an impressive total of some 128 lbs and that doesn’t count its tools and spares or even one of the heavy 105 round cans of ammunition!

Such a formidably weighty and awkward firepower package requires special tactical consideration and the Army’s standard “leg” infantry battalions grouped Fifties in a heavy weapons company. There, the gun was served by a crew of five; gun commander, gunner, assistant, and two rifleman/ammo carriers.

Even when broken down into major assemblies and distributed among the crew, the whole system presented a considerable burden to these men who were already carrying packs heavy with rations and personal gear. Not surprisingly, it is said that most of the ground mount guns’ combat action was in defensive positions, placed for a commanding view of the terrain and well dug in.

Wheels and Tracks

For many a GI and Marine in WWII the real glory of the M2 Heavy Barrel came as a flexible mount vehicle gun. When carried on everything from tiny jeeps to Sherman tanks, the considerable weight of old “Ma Deuce” was of virtually no consequence compared to her hitting power and extreme range. In ring mounts on cargo trucks, on pedestals in weapons carriers, and in groups of four on halftracks, she shot down strafing enemy fighters and killed legions of enemy infantry long before they could get close enough to bring their own small arms to bear. “Ma” could be a mean old gal to those enemies who were luckless enough to cross her long and wide path.

Korea and Vietnam

Containing the evil intentions of our Communist adversaries has been and continues to be a bloody challenge for America. Scarcely five years after WWII ended, we found ourselves at war again in Korea, this time fighting our former Chinese allies backed by our former Soviet allies. The struggle resumed in Indochina as we tried in vain to keep South Vietnam from being overrun by Communist guerrillas and North Vietnamese regulars — again backed by the Chinese and Soviets. Ma Deuce was always there, but even she couldn’t overcome the lack of political will of our gutless politicians who all but guaranteed that those Americans who fought, were wounded, captured or killed, never really had a chance of winning.

In Part 2 of this in-depth examination of John Browning’s masterpiece we will visit a fine unit of today’s US Marines as they introduce some of the Corps’ newest officers to its oldest infantry weapon. Be there next month on Quantico’s Range 7 to examine how Ma Deuce works, how she is pampered and prepared for action, and how she performs her role as the world’s best heavy machine gun. Don’t miss it!

Homework Assignment

Terry Gander, editor of Jane’s All the World’s Infantry Weapons, has recently produced a fine hardcover book on the .50 cal. The Browning M2 Heavy Machine Gun (PRC Publishing, London, 1999, now available from the Military Book Club) does an excellent job of telling Ma Deuce’s ongoing story in authoritative text and great photos. This is a welcome expansion of two classic works with extensive information on both ground and aircraft Brownings; Konrad Schreier Jr.’s Guide to US Machine Guns (Normount Technical Pubs., Wickenburg, AZ, 1971) and the grandaddy of them all, George Chinn’s The Machine Gun, Vol. 1 (Dept. of the Navy, 1951)

General Data for M2 Heavy Barrel Machine Gun on M3 Tripod

Caliber: .50 inch / 12.7 millimeter

System of Operation: Short recoil. Fully Automatic & single shot

Cooling: Air

Overall Length: 65 inches

Barrel Length: 45 inches

Feed Device: Disintegrating metallic link belt, 100 rounds

Weight: Gun 84 lbs. + Tripod 44 lbs. = 128 pounds

Muzzle Velocity: 3,050 feet per second (2,080 mph)

Maximum Effective Range: 1,800 yards

Maximum Range: 6,800 yards (3.8 miles)

Cyclic Rate of Fire: 500 rounds per minute (8.3 rps)

Sustained Rate of Fire: Up to 40 rounds per minute

Ammunition: Ball, Armor Piercing, Incendiary, Tracer, Specialized

Characteristics of M2 Ball Cartridge:

Overall length 5.45 in.,

Overall Weight 1,813 grains;

Bullet length 2.5 in., wgt. 709.5 gr.;

Powder charge 235 gr. IMR 5010

Penetration (AP M2 at 200 yards): 1 in. armor, 14 in. sand, 28 in. dry clay

Crew: Gunner, Assistant, Ammunition Carrier

About the Author

Robert Bruce is a former infantryman, tank crewman and military intelligence analyst. An internationally published magazine and book author, photo journalist, archivist and lecturer, he has been shooting, evaluating, and writing about the world’s infantry weapons for more than thirty years. Robert is perhaps best known for his book THE M1 DOES MY TALKING! an archive photo history of the famous Garand Rifle, as well as GERMAN AUTOMATIC WEAPONS OF WWII and MACHINE GUNS OF WWI. He also regularly supplied the “Archive Photo of the Month” featurette for the old Machine Gun News and now, as space permits, for Small Arms Review.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V3N4 (January 2000) |