By Dan Shea

Last Month in Part I of The Interview, we ended with the following quote from Reed: “We have been able to take the ideas and the needs of a customer, and build solutions to those needs. My talent has probably been to think outside of the box. Gene Stoner told me something interesting one day; he said, “I believe when you become an engineer, and they teach you the disciplines, you learn that one and one make two, and that you have to do it this way because this is what the book says to do, I think it prevents you from becoming a true designer. If I sometimes knew what the engineering math was on some of my designs before going all the way through with them, I probably would’ve quit earlier.”

SAR: Interesting quote from Mr. Stoner…

Knight: There are a lot of things that I’ve done not knowing it “couldn’t be done.” When we built the silent revolvers, everybody said, “That just can’t be done.” We thought, “Well, maybe it can.” There was a lot of trial and error and a lot of work. It was in 1989-90, and we needed a very, very small gun that was able to be taken apart and put in a briefcase, have a 200 meter range, have good optics, night-vision, and silenced capability. We built a .30-caliber silent rifle on the Ruger Redhawk frame, with a removable shoulder stock and an integrally suppressed barrel using custom case-telescoped ammunition. We used a very heavy .30 caliber bullet that was case-telescoped inside a .44 Magnum cartridge case. This was almost “Hollywood quiet,” and accurate out to 200 meters. It fit into a very small briefcase, with night vision capabilities. Those were the types of things that I got up early in the morning to go do, because I was excited about doing it, and I had a full team of people that really were passionate about making those things work. There was a requirement for that rifle/ammunition combination, and the revolver had another advantage in that after you fired it, you did not leave the brass cases behind like a semiautomatic, and it was better than a bolt gun because the cartridge is laying on the ground. It was a great project, a fun and very challenging project. Art Hoelke, my production manager today, worked on that project. A lot of things that we developed were just started by thinking, “Boy, that’d be neat to build” and we ended up in production. We’ve also built dozens of things that haven’t gone anywhere. That’s just the way it works.

SAR: You had the Mark 23 program.

Knight: We had teamed with Colt on the Offensive Handgun program back in the ’80s, and we built the suppressor. I had already sold Colt the design of the All-American 2000, which they were building, and they took that design and built a .45-caliber pistol based on it. The barrel rotated, moving straight back, which lends itself quite well to mounting a suppressor. H&K built a suppressor on their pistol candidate. The Colt gun and the H&K gun went out to test, and the H&K gun won. It had a plastic lower receiver and it had some other advantages in that the Colt gun was heavy, and it had some other disadvantages. But our suppressor was better; it was the first time that the Navy had ever seen a total of 40 dB drop in a handgun.

We were actually getting an honest-to-goodness, 162 dB starting pressure at one meter from the muzzle, and 122 dB with the suppressor attached to the gun. They either advised or requested HK to come pick us up as part of their team. HK was pretty negative about doing anything outside, because they had their own design team and they did their own manufacturing. They did pick us up as a subcontractor, and we built the suppressor, and if there ever was a suppressor that has become known as an “Energizer Bunny,” it would be that suppressor. I have a suppressor that has 250,000 rounds of .45 ammunition on it, and it’s still going. It’s noisier because it’s filled with lead and particles, but it’s still going. The user wore out three pistols with that one suppressor.

SAR: You mentioned the All-American 2000 pistol.

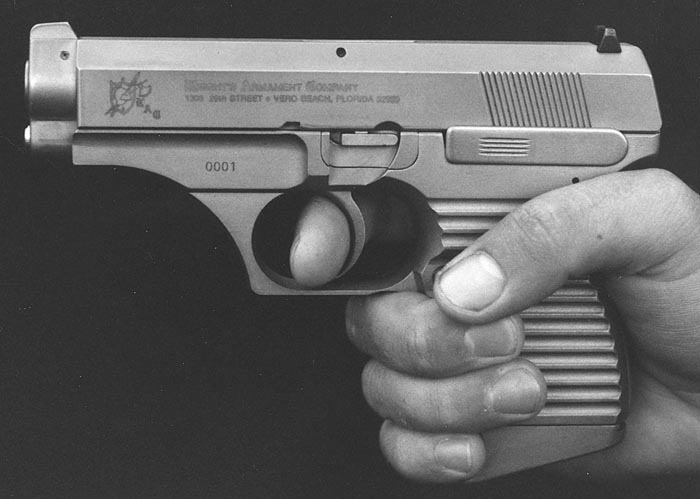

Knight: Gene Stoner and I woke up one Monday morning, figuratively speaking, and found ourselves with no military contracts. We would sit down at lunch and say, “What in the world are we going to do from here?” I’d been over visiting Henk Visser in Holland, and Henk said that he had a pistol that he had bought the manufacturing rights to that was a very small, compact, 9mm. Gene and I had talked about it, and Gene said he had a better idea. We sat down and started talking about it, and so we came up with ideas and started building a few little parts, lots of changes. We finally ended up building this pistol, the All-American 2000 as it ended up being called. The initial concept was a very small, compact, double action only rotary barreled pistol.

Trey: As far as from a design point, my dad brought the trigger mechanism to the table…

Knight: … and Gene brought the rotary barrel. The concept was based around an idea that when you picked up the pistol, it was always safe, there was no stored energy in the firing pin and no stored energy in the cocked hammer. You could lay the gun down, it was ready to go, and it also did not have any stored energy. You picked it up and had a very light double-action trigger pull that you pulled the trigger all the way through, and it pulled the striker back and caused the striker to hit. That concept was similar to what Glock later picked up on. We started building some guns. Gary French, who was the President of Colt, (owned by Colt Industries at that time), knew they were looking to sell Colt because they’d just lost the M-16A2 contract to FN, and their factory was downsizing. Colt Industries decided to divest themselves of Colt Firearms. Gary French looked at his list of all the things that they had that were on their future designs and future capabilities and the one thing they did not have was a good 9mm pistol. Gary talked to me and said, “How about your gun? Could we talk about manufacturing it for you?” We struck a deal, they were going to manufacture it and pay us royalties, as well as an up-front fee. This was the first gun that they’d ever bought that they did not manufacture any of the parts, it was all subcontracted to outside vendors. We were supposed to receive a down payment, which we got, another in three months, which we got, and then they said, “I don’t know that we want to continue putting this money into the costs of this thing. Is there anything else that you would consider that we could do?” I said, “Well, do you have any old guns laying around up there?” Colt said, “We have tons of guns in our pattern room and on the shop floor.” We grabbed old shopping carts that had those little rattly wheels on the front, and rolled through the wooden floors where the original plant was. We went into all these old dungeon-looking dark rooms, with racks and racks of old guns, and we just scooped guns up and put them in these shopping carts. Two or three of us did this, and there were hundreds of these old guns, some prototypes, some other manufacturers’ guns, different types of guns that you could ever imagine. We swept them up into the carts and that’s what Colt traded me for one of the payments. In retrospect, nobody knew that machine guns were going to skyrocket in value, and some of these guns are very, very significant.

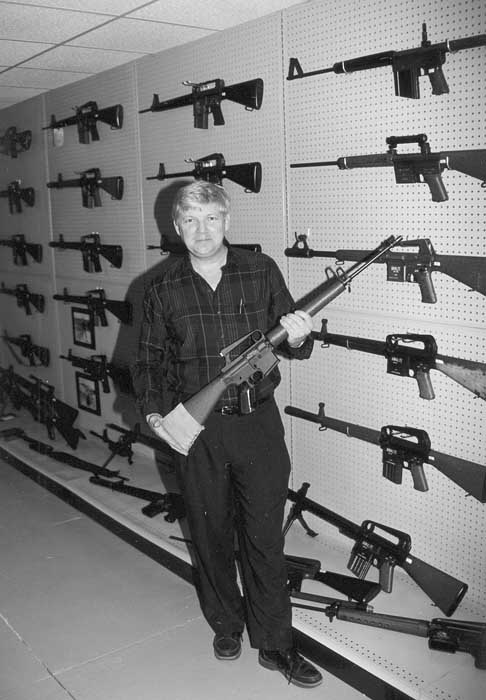

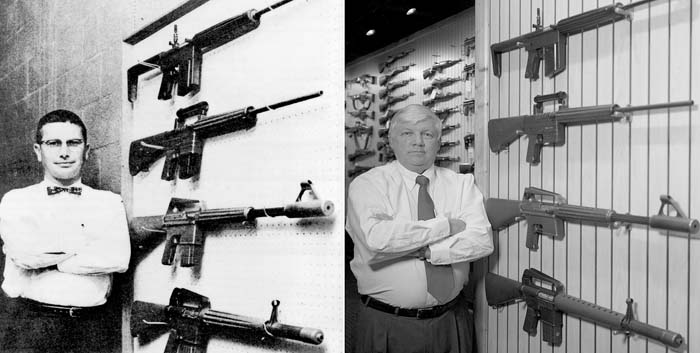

SAR: This leads us into one of your passions, which is the reference library of firearms that you have.

Knight: Exactly. I can’t emphasize enough how important it is to have these reference collections available for study. I’ve been very fortunate that I’ve been at the right place at the right time on many of these deals. I got a big part of the Armalite collection when it went up for sale in the late ’80s. I also bought a very big part of the Colt collection when it went for sale. I got all of Sam Cummings’ machine guns that he had left the last time that he visited the United States, and I bought the whole Fairchild collection. That was kind of interesting – Gene Stoner was negotiating with Fairchild, because Colt had not paid them their last royalty payments. In one of my trips to Colt, I talked to Bob Morrison, and I said, “I don’t know how successful we’re going to be doing a deal with this pistol that you want to buy because Colt has not paid Gene Stoner his royalties for the M16 for the last two years.” Bob Morrison said, “You’re kidding me.” The payments were being paid from Colt to Fairchild, and Fairchild divided those things up and gave Stoner money and Stoner’s ex-wife money, and some to the Cooper-McDonald family. Everybody got a piece of this chunk of money. Gene had mentioned to me that he had recently talked to the lawyer from Fairchild, and that there was one gun that he had built in his garage that he wanted back and that was in the Fairchild collection.

I contacted the lawyer, and said, “Mr. Stoner has a gun that he had built in his garage that’s in the Fairchild collection, and I’d like to see if I can get it back,” and he said, “No, there’s no way that we’re going to dispose of these guns, because we have to have proof of concept because we’re in a position for a possible battle with Colt over the rights of who owns the technology. The patent’s long run out by now, but we had sold the know-how to them, and we have to prove that we own that know-how.” I said, “Actually, what you need is an expert witness to do that, and I’m your guy. I know this backwards and forwards. If you sell this collection to me, I will promise to keep it until these dates run out,” which was in seven years. He asked, “What would you give us?” I said, “Well, let me just think about it.” I thought about it, and I said, “Let me give you a check for X amount of dollars,” and he said, “Okay,” so I wrote a check out for X amount of dollars and said, “Consider this a deposit.” He said, “Okay.” Two weeks later I went up to their office at the Dulles Airport. I met the president and I sat down, and said, “I’d like to talk to you about this,” and he opened up this closet, about four foot by four foot, and there were many of the prototype AR-10s and M16s that Fairchild had thought that had been lost for all these years, stacked in the corner like cordwood. My jaw dropped. Here were all these prototypes, I think my heart actually stopped, because I’d never even heard of some of these guns. I made an offer and he said, “Okay, well, put it in writing and come back.” I went back two weeks later with Form 3s with all the serial numbers. I said, “This is my offer,” and he said, “This gun number one, we’ve been told that it is worth X number of dollars just by itself.” I said, “You think it’s worth that, it’s not worth that to me, so just take that out of the collection, and I’ll give you this for everything minus gun number one.” He said, “Gun number one’s not worth this much money?” I said, “Not to me, it’s not.” He said that they would go out and get more offers, and I said, “That’s fine, why don’t you give me my check back?” He said, “That’s another problem. “We’ve spent your check and we don’t have your check to give back to you.” I told him I had an appointment at ATF to have these Forms signed, and didn’t want to miss it, and that I thought we had a deal, and they spent my money as if we did. He signed the Forms, I went down to ATF that afternoon. The next morning I went and picked up the Forms, brought them back to him, put those guns in my van and headed back to Florida.

SAR: So you did really, really well on that trip, Reed? [laughter]

Knight: Not all those trips are good trips, but that one was one that I’d have to say that was a very memorable one. Armalite AR-15 number one that had been given to General Wyman, a bunch of the Dutch AR-10s of all different configurations, it was just amazing. I now had a very interesting collection of AR-10s and AR-15s from Colt and Fairchild. That’s where my focus was, to save that history. Most of the prototypes of the Cadillac Gage firearms came from Gene Stoner. He also had the rifles he built in his garage, M5 and M6, and I found the M7 (AR-3, 7.62x51mm caliber rifle) in California. The gun which Gene was looking for, which was referenced in the patents for the M16, was actually Gene Stoner’s M8, which later became the AR-10. It was the only one that was in .30-06 rather than .308. It had a steel receiver.

Trey: I remember Mr. Stoner’s comments about walking into a room where a large portion of his life’s work, all his “children” that were scattered all over the world were now together in one spot. He jokingly said in his dry sense of humor, “I would have just sold them all to your dad if he wanted them.”

Knight: He was excited about me going back and finding all these designs that were parts of his whole life, and bringing them all together in one place. It was like I was chasing firearms all over the world by serial number. I got all of Chuck Dorchester’s collection; he was the president after Fairchild sold Armalite to Dorchester and his group. I have had the chance to have a bit of fun with this as well. I remember talking to Ed Ezell, and he talked about these missing Armalite guns. Everybody had known that when Fairchild sold Armalite off, they sold them to a group – basically, it was George Sullivan, Dorchester, Miller and all the crowd that were there. As I mentioned, one of the things that Fairchild demanded was that they keep was all the AR-10s, all the AR-15s, all the rifles that had proved the gas impingement system, because that was what the patent was about. That large group of rifles left California and went to Hagerstown, Maryland, which was where the Fairchild main office was. To everybody’s knowledge, those rifles were lost in transit, and no one had ever seen those again. Back to Ed Ezell – after I obtained the Fairchild collection, I wrote Ed an anonymous letter, and the letter started off like this: “Mr. Ezell, I understand that you are at the Smithsonian Institution, and I have in my grandpappy’s barn a whole bunch of old guns that when my daddy comes here from California to take them to Hagerstown, Maryland, but when he got home, Mama was in bed with Uncle Johnny, and Daddy shot him, and Daddy went to prison, and these guns have been in the barn ever since. Daddy died in prison. I will trade you these guns if you promise to give me a new motor for my fishing boat.” [laughter] I took a crate, and I got some chickens and eggs and hay, and put the prized, one of a kind prototype AR-10s and the prototype AR-15 in the crate with eggs and a chicken standing over the top of ‘em, nesting on this crate of rifles. I had all these boxes stacked on this old, rusted out flatbed truck. I sent that to Ed, and his secretary got the letter and thought it was a hoax, she didn’t know that the pictures were real, and she tossed the letter. He never saw it. It was absolutely perfect, the best setup ever, and he never got it. Later, I told Ed that I found those rifles, he was absolutely excited. At least he did get to see these rifles before his untimely death.

SAR: As part of your passion for collecting and as a Stoner historian, you at one time organized a reunion for Armalite. When was that?

Knight: 1992. All the cast of characters were there. They all came to talk about the old days, and that’s where I met Mac McDonald for the first time. He was Bobby McDonald’s son, of the Cooper-McDonald Family. At dinner he proudly told me that he had M16 number one. I pursued him for years, and just within the last eight months, he finally decided it really belongs down in this collection. I now have AR-10 number one, M16 number one, and prototype AR-15 number one.

SAR: They’re all where they should be, in one place.

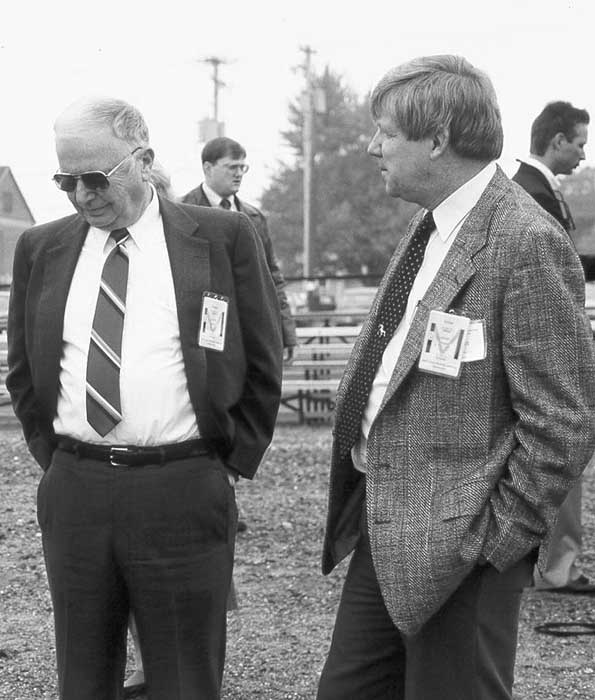

Knight: We’re sort of putting everything back in the box. At the Armalite Reunion, everybody got a chance to see all their old friends. Everybody kind of had a pretty good time. I had a tough time getting some people’s addresses, and getting some people there. Gene and Barbara Stoner were there of course, Chuck Dorchester was there, Tom Teleson was there, and Jim Sullivan (L. James Sullivan). Arthur Miller I couldn’t find.

SAR: Art’s still living in the same house that he bought back in the Armalite days; we have a big Interview with Art coming up in SAR.

Knight: I look forward to seeing that. Let me see… Tom Nelson, Henk Visser, Bob Sullivan and Saxby were there. Bob was the janitor and he was George Sullivan’s son. Saxby was bringing me some new ammunition. Let’s see… Al Paulson, Doug Olson, Eric Kincel, Dave Lutz, Stoner’s youngest daughter Dee Dee Stoner, Susie Klienpeld and Art Klienpeld. It was a big party, and everybody came and talked and had a few drinks and dinner at the Holiday Inn on the ocean. We came out to the plant and went through the collection, talked about the guns. Lots of interesting things about what people said and what they did, setting some records straight, telling anecdotes. It was great! I learned a lot about the history, put the pieces together.

SAR: Right around that time there were a number of reunions or meetings organized. Were you involved in the Kalashnikov-Stoner meeting?

Knight: Yeah, I was. Ed Ezell put together a meeting for Gene Stoner and Mikhail Kalashnikov, and it was the first time that Kalashnikov had been out of Russia since the wall came down. It was a very interesting meeting between the two of them; it was very cordial. That’s the first time that I met Kalashnikov. I was there about a week, they had two campers out in West Virginia, they were at a range, and the two of them would meet each day and go and talk and have a good time. General Kalashnikov had an interpreter. It was a very interesting and enlightening meeting, where the “Father of the M16” the main rifle of our armed forces, met the “Father of the AK47” the main rifle of many of our opponents.

SAR: The flagship project that your companies were working on were the rail systems.

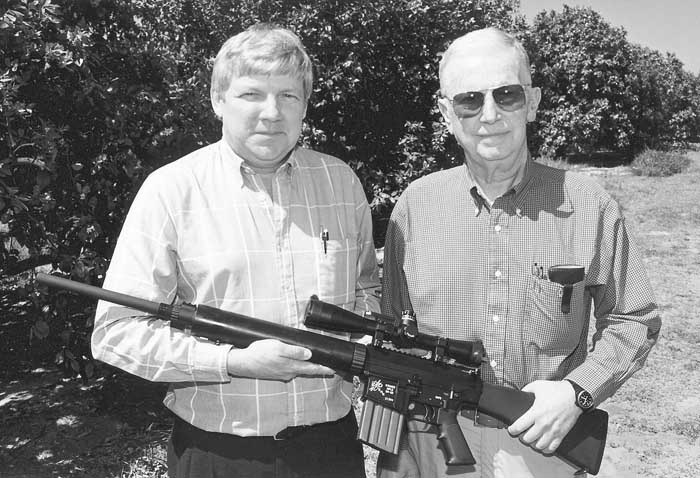

Knight: I guess we’ve probably built close to 750,000 rails for M4s, M16s, and the like. It’s been a good product for us. We made suppressors, some low production dedicated systems, parts, mounts, and had designed firearms, but not built them completely. The military told us that there was a need for a very accurate .308 rifle. Gene came up with the idea, and said, “Why don’t we use some of the parts off the M16; let’s try to make as many common parts as we can, pistol grip, butt stock, screws, plungers, springs, gas key, see how many parts we can use.” We started designing for parts that would be in common between the two guns – the M16 system and our new 7.62x51mm rifle. The other idea was to manufacture the gun so that the training would be the same on the 7.62 rifle. That was the start of the SR-25 rifle. “Stoner Rifle-25,” we took AR-”10” and AR-”15” and added them together to get 25 as the designation. We took the best of the AR-10 and the best of the AR-15, and all of our experience, and the rifle started shooting very, very accurate right out of the box. We built a few more, then we geared up to build it, and we started selling them commercially.

SAR: What was the most challenging part of that project?

Knight: Building a good magazine ranks right up there. Plenty of challenges anyway, and then the military match ammunition, not even the M118LR yet, was thirty-two thousandths longer than SAAMI spec. We built the SR-25 to use original AR-10 aluminum “Waffle” magazines, which I had 10,000 of. Thankfully, I didn’t have to build a magazine at first. When we started to build the magazine, then it became very challenging, how to make the magazine work. The magazine is a part of a firearm that looks to be quite simple, and people think it’s pretty easy and straight-forward, but it’s a feeding mechanism that is dynamically moving and there are so many nuances that affect the reliability of a magazine. Because it appears to be so simple and straight-forward, I think that it’s often overlooked as being as important part of a weapon system as it really is. Very few people spend a lot of time on designing and developing a magazine, and that comes back as trouble later. The event of feeding the cartridge out of the magazine into the chamber happens very quickly. Feeding the round and presenting it to the chamber, and extracting and ejecting the old cartridge case happens in such a short period of time, and it’s all happening at that intersection of the firearm. This is generally right at the throat of the chamber, it’s almost Grand Central Station for interior activity, it’s at high speed, and anything that doesn’t keep up the pace or gets in the way and the system doesn’t work. The magazine has to be top quality and properly engineered or your reliability goes away.

SAR: You have two different ways of firing the system, suppressed and un-suppressed.

Knight: Yes, and that complicates things further – and then there are different types of ammunition, different grain weights of bullets. This system is what has morphed into today’s SASS M110 rifle for the military. We built some guns for the US Army to test way back in the early ’90s, and they came back with a list of around 11 features that they wanted improved on. I was told that if we could not improve on those things, we weren’t going to have a program. We worked on those things for about a year, and we finally got those improvements done. Then we started actually manufacturing, and that became a good enough rifle that the Navy SEALs wanted to buy it, and it was designated the Mk11 Mod 0. We probably made between five and 10,000. Some of them were sold in the civilian market. The early ones we sold commercially were overruns that we built for the Navy SEALs. We have not built a lot of SR-25s. The very early SR-25s, most of those were all 24-inch barrel, match guns, with round fiberglass hand guards. The Mk 11 Mod 0, we haven’t built a whole lot extra because our production has been pretty much taken by the military. As I mentioned, we won the contract for the new M110 SASS- “Semi-Automatic Sniper System.” The chassis is based on the Mk 11 Mod 0, but there are about nine different improvements that we’ve made over the Mk 11 that has made it into a better rifle. We’re building thousands of those now for the military. Over a 15-year period, our first purpose-built Knight gun, the SR-25, has now evolved into the new M110 SASS rifle. Our first program is still alive and well, and serving the US military. The Navy has changed the Mk 11 Mod 0 to the Mk 11 Mod 1 and Mod 2.

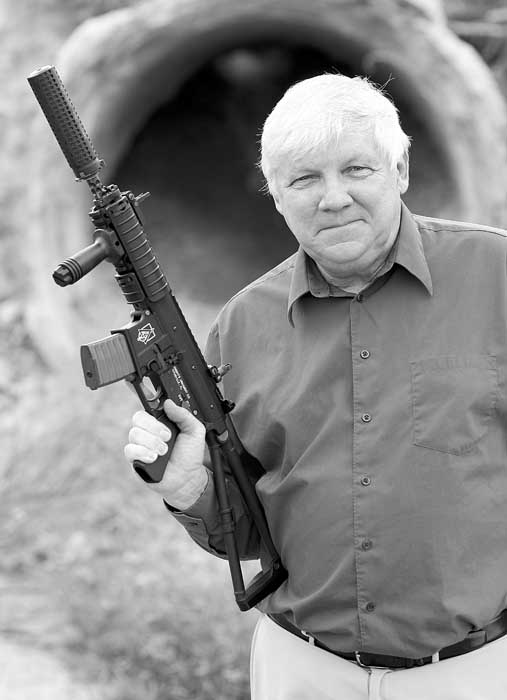

SAR: Your companies have built many of the firearm items in use today: suppressors, RIS and RAS rail interfaces, sniper systems, your own line of AR-15/ M16 rifles called the SR-15 and SR-16. At one point you took on the idea of a semiautomatic .50 caliber…

Knight: I guess I should address that. I would call myself strict on or kind of stubborn about what we make. If I can’t put out something that I’m really, really pleased with, I’m just not going to sell it. Stoner designed a .50 caliber gun, and we built some, and they worked very, very well, but when we started doing endurance testing, we had some problems with some bolt cracking, and of course that became a liability issue. We redesigned that, and just about the time we got that redesigned, we ended up having to step up to meet the demand for the September 11th issues. One thing led to another, and I have parts and pieces for the first 100 guns that are about, I don’t know, 50% maybe done that are out there, that I just haven’t put the engineering effort into it to really make me happy. It’s dormant now, and we’re a lot smarter than we used to be. We can build stuff a lot better than we did ten years ago. Our company is a much bigger company and has many more capabilities than we did back then. I’m sure if we build the rifle again, we could overcome some of the design issues that we had on the early prototype guns.

SAR: Parallel to that project, you were working on an AR-15-style weapon that had the input of Mr. Stoner, yourself and your design working team. The SR-15 rifle.

Knight: The SR-15 is semiautomatic and the SR-16 is select fire. It’s a 5.56x45mm rifle that uses a gas impingement system, M16 family, and we improved many things that we think that makes it a superior, reliable weapon. We built quite a bit of parts and pieces to those guns. We build all the production ourselves. As long as you control your parts, you can control your quality. The only person you can blame if you don’t get the things done is yourself. We’re very focused on building pretty much all of our parts ourselves. We do buy some parts on the outside, and our SR-15 we’re probably going to buy some parts on the outside, only because there’s other people out there who can build them cheaper than we can, and if they meet our quality standards, then we’ll probably buy parts and pieces from them.

SAR: Reed, you have almost 40 years experience with the gas impingement system of the AR-15, and 30 years experience dealing with the original designer, other designers of the system, and have intimately been involved in testing and being around all the original designs, the prototypes that worked and didn’t work. In today’s world, we have the M4, the M16A2, the M16 variants, there’s about nine or ten million out there. You are in active production of a gas impingement-style system. Frequently the answer to all the issues in the AR family is the idea of a drop-on piston system. You also have made piston-operated guns yourself that are in somewhat of the Stoner family.

Knight: Dan, I’m like everybody else, I’m striving to find a better mousetrap. I want the best of the best, to be able to improve things. I should probably qualify my statements here this way: In our testing over the last two years, we have fired about 1.3 million rounds of 5.56mm. In that process, we have come up with some things that we think improve the M4 rifle in its baseline design. We’ve also built some piston-driven uppers that drop on the basic lower. If there is anything that I am really convinced of, it’s that you should not go and think that the piston-driven upper system, based on the AR-15 chassis, is some type of a major improvement, because in fact, we have found it not to be. If the M4 is properly maintained, and if the gun is kept clean, it will run and do the job that is needed to be done. On the other hand, if you don’t use the tool as what it was designed to be, it was designed for, then it probably is going to cause you some issues. The major thing that we’ve seen with pistons is the bolt cracking of the locking lugs at maybe a higher rate than what we think it should be. The gas piston system does not help that issue, and it exacerbates the bolt cracking. If you take the things that were allowed to be done to improve the gun, such as some of the things that they’ve done for the HK 416, if they were allowed to do that or do some product improvements on the M4, the M4 itself I believe could have a higher reliability in its own design. Unfortunately, there are some things that you help when you go to the piston-driven upper, but there’s also some things that you don’t help. One of the major things is that in a gas impingement system, when the gas pressurizes the chamber in the bolt carrier, it actually pushes the bolt forward, and that pushing of the bolt forward, as it unlocks, takes a good amount of load off the back of the locking lugs as it’s unlocking.

That system allows you to have a less stress on the locking lugs while it’s unlocking.

The gas impingement system is pushing back on the bolt carrier, evenly from the inside, and pushing forward on the bolt relieving the rearward pressure on the lugs. With a piston, as you’re pushing back on the bolt carrier, you not only have tilting pressure which is uneven, it’s pulling the bolt backwards, which adds more load to the locking lugs of the bolt as the bolt carrier’s going to the rear, and the faster you drive it to the rear, the worse off it is. If you use an M4 in its conventional barrel length, which is 14-1/2 inches, I don’t think a piston gives you any advantage over a gas impingement gun. I think that an M4 in a 14-1/2 inch barrel is just as reliable as a piston gun with the 14-1/2 inch barrel. The gas piston has added different problems.

SAR: One of those issues is the tilting pressure that’s added using a piston on a standard M16 type system.

Knight: Right, you’re actually pushing down on the top of the bolt carrier. Instead of pushing evenly from the center of the bolt carrier, you’re actually pushing the bolt carrier down. Probably the most significant thing is what I am calling, for lack of a better word, bolt bounce. As the bolt unlocks, the bolt actually turns and bounces back, and as the bolt bounces back, it digs into the upper receiver very significantly right out of the unlocking bridge of the upper receiver. The bolt cam pin is actually digging into the upper receiver. I’ve noticed that on piston-driven guns, it is not present at all in gas impingement guns because there’s still residual pressure that holds that bolt from bouncing back. If you look at the bolt carrier velocities of a firearm with a piston-driven bolt carrier, and you look at the bolt carrier velocity of a gas impingement system, the initial bolt carrier velocity of a gas impingement gun is much smoother and less radical than the bolt carrier velocity is on a piston-driven gun. So as it bounces, and this flat right here digs into, significantly into the upper receiver right there, because it bounces… It unlocks and then bounces back and digs into the upper receiver. Bolt carrier speed and how smooth that start up is, effects how reliable the system is. Essentially, on a piston driven system, it causes the bolt carrier to speed up and slow down, and that jerky motion is just not conducive for reliability and smoothness of the system. The bolt carrier velocity on these piston-driven guns is much higher than it should be to get the same amount of work out of it. All that being said, the gas impingement gun is actually a smoother operating system. Where you do run into an advantage on the piston-driven gun is when you take and shorten that barrel length ahead of the gas port significantly. The amount of time that gas in an impingement system has to travel down that gas tube into the carrier is the time that the bullet’s traveling down the barrel, past that port, until it uncorks from the muzzle.

SAR: Time under pressure.

Knight: Exactly. It’s a time under pressure issue, and if you are able to have the luxury of having a barrel with 7 inches of barrel in front of the gas port, it gets the job done before the bullet leaves the end of the barrel. When you go to a 10-inch barrel or an 11-1/2 inch barrel, that time significantly drops, along with your reliability. The only way to do that is to open up the gas port, and you get a big gulp of air immediately. The rifle becomes sporadic at that point. The advantage on a piston system might come in with a shorter barrel. In my opinion, it’s the only advantage that it has. If you look at the bolt carrier velocity, and you shoot ten rounds with a gas impingement system, and you look at the velocity and you look at the standard deviation of that velocity, the standard deviation, meaning the velocities, and you overlay those velocity curves over the top of each other, the gas impingement system is much, much more concise and reliable than the velocity is for a piston-driven AR type rifle. The piston-driven gun is all over the place as far as its bolt carrier velocity, and its bolt carrier velocity at the back of the gun. The AR system likes a gas impingement system much better, because it’s a much better utilization of the gas.

SAR: That was Gene Stoner’s original design in the 1950s.

Knight: Right. It’s been said by a number of the people that were involved that everything worked really well until they changed the powder, which threw the system out of balance. Instead of changing it by going back to the right powder that it was designed for, they started changing the system, and it’s been bouncing around ever since, fixing the symptoms. The idea of putting a piston system on here throws its own problems into the mess. The piston-driven AR type rifle has created its own set of issues that are going to show up in the field in the future.

SAR: There are problems with the M4 though…

Knight: The gas impingement system is just so much more efficient. That said, if you don’t have a set of good gas rings on the gun, if you have a carrier key that’s worn out or if you have a gas tube that’s worn out, there’s going to be problems. I find it interesting that we have rifles out there in the military system that, some of them have 10,000, 20,000 rounds through them, and we’re comparing them with rifle systems that are brand new. Everybody likes a new broom because it always sweeps clean, and everybody wants something new. These changes need a track record, these systems need to fire as many rounds before we can compare. If there’s anything that I think that we are doing wrong in our small arms for the US military, it’s that we figuratively woke up one Monday morning, and said the M60 was a bad weapon. When and where did we fall out of love for the M60? It was after it got worn out and after the parts were worn out, and then we went out to low-bid, small business set asides as vendors that built parts for the M60, flooded the system with parts that may or may not have worked compatibly with the original parts and pieces. What we did was adopt a gun that was two years older, six pounds heavier, and much longer, and that had some other issues of its own. We adopted that gun “because it was more reliable.” If you would let me add 25% of the weight and 25% of the cost, and all the other things to any weapon system we have, sure, we could build a better weapon. When we started realizing that the M60 wasn’t going to last forever, we should’ve started a program to design a new belt-fed .308 machine gun. This brings me back to our firearms laws and the travesties of 1968 and 1986.

When Gene Stoner and I started working on this 7.62mm belt fed issue in 1989, the very first thing we tried to do was import a PKM. ATF said the law would not allow Gene Stoner to import a PKM – that’s just crazy – when he and I wanted to work on this. It was because it was a Russian design, and it was forbidden to import Russian small arms into this country. I mean, here’s the father of our main rifle caliber weapon, and he wants to work on a new belt fed, and he can’t have access to similar designs because of politics. We just decided not to even bother going down that road, it’s just not worth it. Our country should have started designing a new replacement for the M-60 when we saw that the parts were going to be worn out, and the parts weren’t going to be compatible. I’m hearing similar things right now that soldiers are saying about the M249, that they’re unhappy with its reliability, they’re unhappy with the parts, and maybe we’re going to wake up one Tuesday morning, and say, “Let’s throw the M249 away.” Instead of letting it get to that point, let’s see if we can fix the problems, let’s P-I-P it. A good Product Improvement Program.

The first thing to do is see if that machine gun can be improved, and if we have reached the lifecycle of those guns and they’re worn out, then let’s throw ‘em away and buy new ones. But how could a gun that we have had for 20 years, how can we wake up one Tuesday morning and that gun not be any good? What happened to it? If we have an issue, let’s start developing, let’s start thinking about a new level of M249, let’s start now, and let’s improve it. But there is not anyone that has written and told FN that they have a problem. As far as the Army’s concerned, there’s not a problem.

SAR: You’re talking about a breakdown in communication from the end user to the manufacturer.

Knight: The end user to manufacturer communication is only with a PDQR, and that’s a Product Deficiency Quality Report. When you turn one of those in, it goes in front of everybody, it’s throwing a big red flag up. I think there needs to be something else out there that’s a user failure of equipment report, and that means that, “I have a product that’s out in the field that’s not doing what I need it to do. So, somebody come out here and investigate.” I want the end user to tell me. I want to know if the design is faulty. Are parts built right, but the product isn’t working? Is the end user trying to use his M4 as a belt-fed machine gun role? Either the product is being used for something other than what it was intended to be used for, and it doesn’t meet the requirement, or, if it is not reliably doing the job we have another issue. I have to know as a manufacturer, and the sooner I know, the better. Maybe the end users have longer distances now than what we built the product for initially. Maybe he needs a heavier bullet, which is going to affect the system because you can’t just change ammunition and expect everything to be perfect. There should be a report that a soldier puts together that the Army goes and looks at and determines, is it a faulty design, is he using it wrong, or is it in fact a quality problem from the factory? And we’re not doing that.

SAR: In the First World War there were manufacturers who had representatives go out to the frontlines and talk to the people. In World War Two, both manufacturers and Army ordnance groups went out to the frontline, right out to the front, and talked with the guys. They had to take a ship across the ocean. It seems that there was a disconnect then in the information, and the manufacturers were frustrated then with the communication that came through ordnance groups.

Knight: Exactly. I have had some feedback from the front lines, but as a manufacturer, we need better feedback. I would like to have better info. First of all, I have to say there’s nothing in this factory that I am building that is good enough. Everything here can and should be improved. I can’t improve things and initiate obsolescence to previous designs and previous products, because once you get to a certain point, that design is frozen. If you don’t have vertical integration, so that the products that you have in the future are backwards compatible to products that you built in the past, then sometimes you’re shooting yourself in the foot in the supply chain. You can’t obsolete your other products, unless it’s a major improvement.

Let me run further down the road here, because if I have my soapbox to stand up on, it’s this: I think that we as a country would be making a major mistake to adopt another rifle, other than a rifle that we have in the system if that gun already meets our needs, without it being a significant improvement. What I’m trying to say is I do not believe that the United States should adopt another 5.56mm brass case M16-type weapon. In other words, a weapon that weighs six pounds, utilizes a brass cased ammunition, uses the same magazine. I think we should stick with what we have, but I think that we need to come to the table with new technology.

SAR: Do you think there should be some incremental improvements adopted in the M16 and M4 systems?

Knight: Sure. I think if we can come to the table with an incremental improvement that does not obsolete our inventory of parts, our inventory of training, then let’s do it. If as a manufacturer and designer, I can’t give you 30% across the board improvement, a 30% reduction in weight, 30% reduction in cost, 30% increase in reliability, etc., then we shouldn’t change systems. I think what we should look for in a new system is a 30% improvement before we move ahead and change it all. That’s what we should strive for.

SAR: Do you think that was done in previous generations of weapon changes in the US military?

Knight: I do. I think an M4 is as reliable as the M16 is today. I think when it first came out, there was a learning curve that came behind that, and I think that it had multiple issues with it, part of it was government-caused, and part of it was the manufacturing, learning how to manufacture the gun and all the other things that have to be learned, such things as chrome chambers, such as barrel twists, let alone how to manufacture the rifle. More importantly, I think the M16 over the M14 was a 30% reduction in weight, I think it was a 30% reduction in size, certainly I think today it’s been a 30% reduction in cost. There was a significant increase in hit probability in fully automatic, over the M14. The majority of the soldiers who used the M14 used it in semiautomatic role, and it was a good rifle in that, but in fully automatic it took a very skilled operator.

SAR: We’ve had many conversations about the leaps forward that need to be made, and noted that for the last 150-odd years, we take a brass case, fill it with powder, put a projectile in front of it, and we drive it down a rifled bore. We do it faster, more accurately, automatically, semiautomatically, for sure, but you’ve often brought up that we need to have a major sea change in the ammunition.

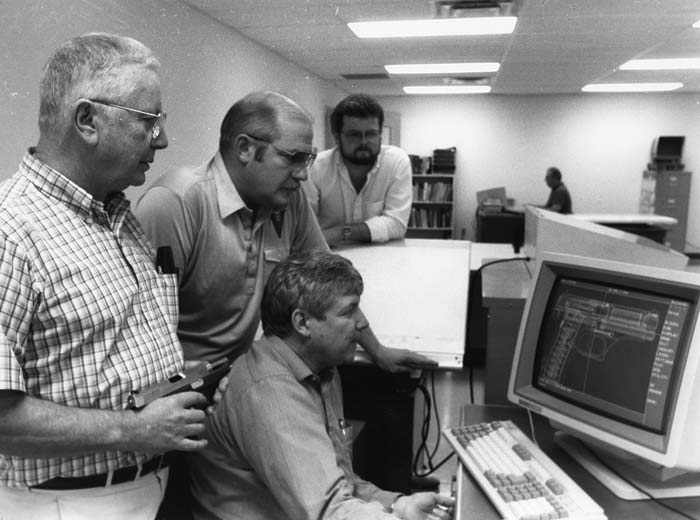

Knight: I’ve said this many times, that if John Browning, Thomas Edison and Henry Ford all came back to life today, the only one that would not be impressed would be John Browning, because we’re still using a brass cartridge case and a bullet and a primer, the same as what he had 110, 115 years ago. I don’t think we’re ready for caseless ammunition, what I think we need is case telescoped ammunition. Gene Stoner built some of the first ones on the ACR project back in ’86, ’87, Steyr had a case telescope round at around that time. Today, AAI and Ares have designs that make an M249-type weapon that’s very significant in reduction in weight among other things. Aside from all that, if we do not start today to develop the next small arms, we’re going to wake up one Monday morning and say, “Now we have to have what’s on the shelf.” And that won’t be a leap forward. Unfortunately, until you build 3,000 or 5,000 or 10,000 of something, you can’t get your manufacturing system nailed, and the bugs out of the product. I don’t want the first one off the line of a new model car that they build. I don’t want the first of anything that’s a new model that they build. That includes products that I build, or Colt, or FN, or H&K. We all have the same manufacturing issues of getting the product tweaked and leaving the new weapon system to what’s “on the shelf” isn’t good enough. The manufacturers need not only R&D but they need production to tweak things. Some of us are better at that than others and the customers can decide. One truly interesting thing I can tell you is that we’ve designed a gun recently building it in a computer before we ever built a prototype. Out of all the guns that I’ve ever built and all the guns that I’ve ever played with and all the guns that I’ve ever handled, we got there quicker with that first gun modeled and done on the computer, than we could have ever gotten building physical prototypes. We found design flaws with finite element analysis that we improved upon that prevented us from having problems, and having to modify later on in the system. And, we’re just one of a number of manufacturers exploring those capabilities.

SAR: You’ve designed several systems recently, including the ammunition.

Knight: I was referring to the PDW. Again, we’re using a brass case on our new ammunition, because that’s what the customer is most comfortable with. I still think the future is going to be built around a lighter system. The next leap forward is going to come from somewhere. If you ask me today, I would have to say case telescoped. The cartridge can be smaller, lighter and more efficient, and you can make the case out of today’s polymers rather than brass at a cheaper cost. Then in the future, that should transition over to either caseless or semi-caseless ammunition.

SAR: What caliber of projectile?

Knight: Well, let’s start at the target, the terminal end, and let’s decide what work we need to do. Do we need 600 foot pounds of energy at 500 meters? Do we need 200 foot pounds of energy at 500 meters? Do we need 600 foot pounds of energy at 200 meters? Or do we need 800 foot pound of energy at muzzle? Tell me first what work you want done by the projectile. If you want to produce a certain size wound cavity, and generally I really think that issue we’ve pretty much defined, the 5.56 is about as small as we want to go. I think we want to have no less than around 1,000 foot pounds of energy at muzzle. I don’t think we need 2,600 foot pounds of energy, like we have on a .308. Tell me the distance. Give me 1,000 foot pounds of energy, and let me go from there, and back up, and then I’ll tell you what bullet weight I want, I’ll tell you what velocity it needs to leave the muzzle, and I’ll tell you how big the system needs to be to give you that.

SAR: The testing that you’ve been doing over the last few decades has led you to be able to model ammunition also?

Knight: Absolutely. With a lot of confidence on results. Again, you have to start at the target, you have to start where the event is going to happen, and you need to look at what you want that bullet to do. How much work does it take to get the job done? How much energy are you carrying in that bullet to get that job done? Then we will move back to the distance that you want to be, I’ll call it a stand-off. But is the standoff 100 meters, 200 meters, 300 meters, 400 meters, 500 meters or 600 meters? The original M16 was actually bought to be a 300-meter rifle. They said, “300 meters is not enough, let’s make it 400 meters,” and went to the next meeting, and at the last meeting they said, “You know what? If we can do 400, let’s do 500, let’s make it 500 meters.” They wanted the gun to be lethal, and lethal at that time was determined to be penetrating a military helmet at 500 meters. Mr. Stoner was shooting the rifle in a .222 Remington lead core bullet, and it was hitting the helmet at 500 meters and was not penetrating it. Gene Stoner went back in his garage, cut the end of the bullet, put a steel tip on the front of the bullet and stuck it down in the bullet, and went back and shot the same .222 Remington at 500 meters, and it penetrated the helmet, and it squirted the lead of the bullet in there like a worm inside the helmet. And he said, “I met the requirement.” And the guy looked at him and said, “No, you didn’t, that’s cheating, you can’t do it that way. It’s gotta be a lead bullet, it’s gotta penetrate the helmet.” So Stoner went back and said, “Let’s take this long case neck and let’s blow this cartridge case because I need another couple hundred feet per second.” They made what they called a .222 Remington Special, and that was the blown out cartridge case, and that later became the .223. He needed just that many more grains of powder to give him that extra 200 feet per second at 500 meters to penetrate the helmet, because they wouldn’t let him use a steel penetrator.

SAR: Knight’s today is the size of other major defense small arms contractors, and there’s only a few of them. You’ve become a force in the field. When you took over this facility, you were overflowing your old facility, and you had a vision for where you wanted to go?

Knight: USOCOM told us in 2001, after September 11th, that we were going to have to double our capacity if we wanted to be in the game and take care of business. I went to the county commission in Indian River County and actually to the building department, and I bought a new building, and I set it on the ground, and I said, “I have to build a new building, because I need it now.” I had about a 60,000 square foot building, and I bought another one sitting there, ready to put up. And after months of trying to do traffic studies and fire suppression studies, and all the things that the county wanted me to do, I found a building up in Savannah, Georgia that I could go to with my 100 employees, and they would give me the keys to the front door. I came back to Florida, planning to move to Georgia. The local people in Bavard found out that I was going to do that, and they knew about this facility that had been left surplus, and they called the governor, then Jeb Bush, and said, “Can you talk to Boeing and can you get Boeing to talk to Knights and see if we can do something?” Boeing called us, and in two weeks we had a deal put together that they would sell me the facility that would immediately stop my problems of having delays and everything else. We bought this and started moving our Vero Beach factory up here immediately after buying it. By the time we went out and bought machinery, and our plan was to go and buy duplicate machinery that we had in Vero Beach, and to put the new machinery in place and operating, and then unplug the machinery in Vero Beach and bring it up here, and then we would be at two times capacity. Before we were able to unplug Vero, we got the word that two times our capacity was not going to be sufficient, that was going to have to be three times. Before we ever unplugged Vero, our first phase was in and we bought another full complement. We had two times capacity before we ever unplugged Vero, and then we brought it up here. Actually, with the efficiency that we have gotten with the new machinery and everything else, we’re at better than five times capacity than where we were. One thing that I was fortunate enough to have is that old man McDonald was really thorough in his design of this factory, and he has 100% redundancy of everything that is electrical and mechanical, this facility had the best of the best of capabilities when we walked in the front door. He built the Tomahawk missile here, with 3,500 employees. He had quite an infrastructure. We’re running about 325 employees right now and well over 100 CNC machines. We have robotic systems that are working quite efficiently. We do have a sound suppressor cell, we manufacture pretty much everything in-house.

SAR: The lessons learned from your study of prior programs that shows in your collection, the Stoner systems, the ARs, all of those things, have you maintained that diligence with your own designs? Prototyping and keeping collections for study?

Knight: I guess you would call it archiving. We probably have not done a stellar job of that. When, as you evolve something, do you stop and say, “This is a different model?” Because it is evolving, and you’re making multiple changes. Do you stop after five changes? Do you stop after six, do you stop after eight? Or do you just stop when you get it finished? Unfortunately, around here, we never get it finished. We’re always evolving. Everything is constantly in change. That has its advantages and disadvantages. The good news is our product has a reputation that it usually works really well, and that’s because we really pay attention to the product, and we really pay attention to how we build the product. And that’s not easy to do all the time. The answer is yes, we do keep a reference library of our own designs as well, but it’s perhaps not as thorough as future students might like to see.

SAR: Regarding the idea of a reference library, you’ve done major expansion back to the Civil War in US weapons. You’ve also started collecting military vehicles and tanks and some of the larger cannons and field pieces. Where do you feel you’re going to go with your collecting?

Knight: I have become somewhat frustrated at the unreasonable prices that I’ve seen currently on machine guns, and when I say unreasonable, obviously it’s what people think that they’re worth, or they wouldn’t be paying it. In order to grow a collection it takes a fairly serious checking account. I looked at going back to the Civil War or that timeframe and bringing that forward up to 1900, and I found those 50 years to be very significant in changes in small arms. We actually did more changes and more development in those 50 years than we have in the last 100. It’s very significant what they did and what they learned, so for the last two years I started collecting that period. I’ve bought Gatling guns and muzzle loaders and breech loaders and different weapon systems that either evolved or dead ended. As I was going down that trail, I started thinking, “What have we done in the past on artillery, and what have we done in the past in HE?” I’m going to call it HE, let’s call it cannonball HE, which it’s not, but let’s say that it is. It’s one more place that the evolution of weapons has caught my interest and I am trying to apply it. I’m now focusing on US weapons and weapon systems of our enemies and allies that are significant. Pretty much anything from 1850 to present, I’m looking at, if the US used it or had any fingerprint on it, then I’m looking to have a sample thereof.

SAR: One of the most important aspects of small arms is passing on knowledge, mentoring, apprenticing and training. There’s been some discussion about an institute or a school. Have you got any plans in the future for this?

Knight: I have to think that I would not have been anywhere near as successful at what I’m doing if I had not had the luxury of having someone mentor me like Gene Stoner, Uzi Gal and Henk Visser did, and some of the people that have been able to direct me and focus me on where I am today. Obviously, my father had a lot to do with it, in inspiring me to go chase what I felt like that I wanted to do, and not just do what other people said. I would rather train somebody that has a passion to do what’s needed than to try to take someone that has the knowledge and try to instill in him the passion. The passion is the driving force. I want employees that go home and read gun magazines, and go home and work on the computer, and go home and eat, drink and sleep what they do. I want them to be excited about what they do. I want them to be as excited as I am about what I’m doing. I joke around that I’m only working half-days now, from 8:00 to 8:00, and it’s how it seems, because every hour that I’m at work, I’m really having a good time, I’m really enjoying what I’m doing. Of course there are days that are discouraging, but then there are days that you get letters from soldiers out in the field that thank you for what you do. I got a letter from a young soldier, said that he was driving in a Humvee coming back from Baghdad, and they stopped and picked up a couple Navy SEALs. And the Navy SEALs got into the thing, and then they got into a firefight, and the Navy SEAL handed him his gun from the back seat while he got set up on the radio to call for support. He said he looked, and coming through the window of his Humvee, the light was shining on the hand guard of the side of the SEAL’s rifle, and he saw “Vero Beach, Florida,” and he said, “I just want to write you and tell you thank you for what you’re doing, and I just want to let you know, would you please take care of my family in Vero while I’m taking care of you in Iraq?” He found security by seeing Vero Beach, Florida on the side of his gun, and he didn’t even know us from Adam’s housecat, and he got that connection. Some of things that you can make a difference with what’s out there. I think, where do we want to go in the future? You know, I’m getting up there, these gray hairs are real, I don’t dye my hair, so I’m getting to a point that I gotta be getting serious about what is it that I want to be when I grow up. I do want to train more young people.

SAR: Do you have an apprenticeship program at Knights?

Knight: We have, we do, we have it for manufacturing, but if there’s anything that I think we’re unique about, it’s we are probably, out of all the small arms manufacturers, we build more of all of our parts than all of the other companies. We build pretty much everything here. And we grow our talent amongst ourselves. We train our people, and we train them in what to do.

SAR: Do you have an active recruitment program?

Knight: We have an extremely active recruitment program, of bringing good people in and bringing them to the table. Bonnie Werner in our HR Department runs that. She’s the Vice President here at Knights, and she is looking for new, inspired, young, talented help. We want people who want to make a difference and want to do something with their lives. They want to get out and they want to learn, they want to know more about how things work, and how they can do things better. Our claim to fame is manufacturing. We changed the paradigm in manufacturing. We have more table space in manufacturing than all the other small arms manufacturers in the United States added together.

SAR: You’re out there cutting chips in a country that is massively exporting work.

Knight: That’s a rare thing in America today. But we control quality in what we’re doing that way. The idea of an institute or a school on small arms is a very active idea, and I want to do it. It’s a lot harder to do than I thought it was going to be. It really is tough! What’s first, the chicken or the egg? Do you have the talent or do you have the people, do you have the people or do you have the talent? Educating people and training them to do what we need them to do is very difficult.

SAR: What would your concept be of a school?

Knight: I remember the conversation Gene Stoner had with me. We went to China, and he was at this equivalent to an auditorium, we’re in this college, their war college, it was 10,000 students, and they would ask Mr. Stoner, raise their hand and say, you know, “What is it you do in 1962?” And he’d answer, and a student would stand up and say, “Excuse me, sir, don’t you mean you did this and did that?” And Mr. Stoner would say, “Well, you know, matter of fact you’re right, that is how…” They actually knew more about his life than he did at that point – they taught a course on him. There was a cocktail party that night, and everybody was there, and he was drinking the local drink, and the guy rubbed up close to him, he said, “Mr. Stoner, tell me the secret,” and he said, “Sure. What is it you’d like to know?” “I want to know where the secret school is in America.” He said, “The secret school?” He said, “Yes, the secret gun school you have in America, because obviously you have to have one.” Stoner says, “There isn’t one.” “No, Mr. Stoner, there must be one. Please, here, have another drink.” And Mr. Stoner came back and he said, “I was at a school where there were 10,000 people that were designing and building China’s future weapons. We don’t even have one that even knows how to spell that.” Until we stop educating lawyers and start educating engineers, if we’re not careful, we’re going to wake up one morning and we’re going to have all the lawyers shutting down our few engineers. The lawyers are going to tell the engineers that we can’t build a nuclear car, we can’t build a whatever, because “it’s against the law.” Until we reach that point where we understand the importance of energy, importance of defending our own country, the importance of being what we are, until we train our people, until we educate our people again, until we are producing again, we’re in trouble. When I put an ad out in the paper and say “help wanted,” I get plenty of people that come to the door that do not have any experience at doing anything at all. I get ten times more than I need for that, and I get one-tenth of what I need of the educated people to run machinery, or to weld or skilled individuals. We’re not training our people to do skills and skill sets. It’s to the benefit of the manufacturers to start doing that training themselves, if they want to have a workforce that moves into the future.

SAR: Would you be teaching small arms design or would you be teaching manufacturing process?

Knight: All of the above. Engineering, CAD, model-making, prototyping, testing. You know how many people don’t know how to properly test a product? They don’t know how to get to the results that they’re looking for. Mickey Finn and Don Walsh and I had to agree on suppressor testing in the early ’80s, just to establish a baseline. A large part of our work is designing proper, valid testing protocols.

SAR: If you were talking to a young person today and they were thinking that maybe someday they’d like to run their own business, do you have any advice you’d give them?

Knight: Yes. You’re going to have to work real hard to be successful, no matter what it is. You’re going to have to be passionate about what you do. It’s very hard to be successful unless you really work hard at doing what you want to do, and you need to have an idea of what that is. That doesn’t mean you can’t change your mind, it doesn’t mean that you can’t stop and say, “I don’t want to be a welder tomorrow, I want to be a lathe operator tomorrow,” there’s nothing wrong with that, but be the best you can be. I don’t care if you’re sweeping the floor. Be the best you can be, and be the best floor sweeper that there is in that company. Be the best of everything that is there, and learn all you can about what you’re doing. I don’t care what it is. I don’t care, if you’re learning how to paint, or how to run lathe, learn everything you can about it, and be good at it, and be the best that there is, and most likely you’ll move up the chain. I’ve had a lot of things that have been major changes in my life, breakthroughs, things that, without those things having happened, I would not be where I am today. My father and my mother being supportive of my chasing of the rainbows, my meeting Gene Stoner, meeting Uzi Gal, finding different opportunities that have knocked on the door. Now, I do believe that you can be lucky and catch a big fish, but remember you have to put the bait on the hook, and you have to put the hook and the bait in the water, and then you have to be patient to catch the fish. Most of the time you have to make your own luck, and it isn’t always going to work out the way you want.

Finding Stoner’s M7, the AR-3

Armalite Rifle (1999-2000)

AR-3 is a semiautomatic rifle that disappeared forty years ago, but somebody had turned it into a gun shop, and this guy had bought it from the gun shop about 20 years ago. He calls and talks to one of my salesmen, and of course my salesman said, “You don’t know it, but my boss has every Armalite rifle that’s ever made. You couldn’t have anything he doesn’t have.” This guy says, “Okay, thank you” and hangs up. He calls back about a month later and he gets a hold of my secretary, and he says, “I’m telling you that I have a rifle that your boss needs to see.” She said, “Why don’t you email me a picture, and I will show it to him?” I was walking by her desk one afternoon, and I see this picture of the AR-3 that I had never seen, and I had pretty much seen every picture that had ever been made on the AR-3. I was shocked. I couldn’t get the words out of my mouth. “Where did you get this picture?” I asked. She said, “This guy’s been bugging me to send this picture from California.” I said, “Get me on a plane, I am going to California, I have to see this gun.” I flew out to Sonoma, California, and met with this guy, and the gun was, in fact, the AR-3, Stoner’s original he made in his garage, his M7. We cut a deal, and I got on an old prop driven plane through LAX. I put the gun in a little brown plastic case and checked it. I was just so excited that I had found this gun; it was the last of the four guns that Gene built in his garage. I now had all of them. The pilot announced; “We just put the gear down to land at LAX, and the landing gear light shows that the landing gear did not come down. We’re going out over the ocean and dumping our fuel, and then we’re flying back by the tower, there’s still enough light for them to see us. If our landing gear’s down, we’ll try to land, and if the landing gear is up, they’re going to foam the runway and we’ll belly land. Y’all be prepared for that.” I got on my cell phone, called my wife and said, “I just wanted to let you know, if you don’t hear from me again, that I just, well, you know, just tell everybody I said hello.” The stewardess walked by, and I said, “I need to get down in the bottom of this plane,” and she says, “What’s so important?” I said, “Well, I got something down there I need to get,” and she said, “What could possibly be that important right now?” [laughter] I said, “I really can’t say, it’s really immaterial what I need to get. I just need to get down because if you land on the belly of this thing, it’s gonna ruin what I have down there underneath the bottom of this plane.” And she said, “Well, the bottom line is you can’t get from here to there without being on the outside of the plane, and that’s not going to happen.” We were flying low past the tower and from one end of that airport to the other, there was nothing but red and blue lights flashing and everything. I wondered what in the world all these fire trucks were at the airport for. I really had no idea they were there for us. The gear was down, so we came back around, landed, and I ran over and got that rifle. I walked over to Delta, and handed them that gun case, and said, “I want you put this on that plane, I want you to make sure it’s protected.” When I got home, I took that gun out of the box, I put it on the wall, and I still won’t let anybody pick it up, because it’s just very important that it stay on the wall with the other three and nothing happens to it! It’s a treasure hunt, I found a relic, an artifact, that was just so important to the history of these systems. The chase is exciting, and Gene Stoner was just as excited about the other guns that I found at Fairchild. Of course, he was not alive to know that I did find his last gun that was missing, but I like to think that I completed part of the quest.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V12N6 (March 2009) |