The Japanese Rifleman of 1941 would not have looked out of place in the trenches of 1918.

By Dan Szatkowski

The War in the Pacific

More than half a century after the momentous events of the war in the Pacific, it is difficult to come to terms with the sheer size of the war and its overwhelming geography. It was more than just a war between Imperial Japan and the United States, it was a vast war in which Japan continued the European struggle to dominate China. It was a war to displace European colonialism and condescension, a war to allocate the wreckage of French, Dutch, German and British imperialism. It was a war of little wars within the global struggle. While the European powers were locked in battle with Japan’s Nazi allies, Thailand went to war against a weakened France. The Australians saw their manpower and equipment drawn off by a desperate England. The Filipinos saw the opportunity to displace a decadent foreign army of occupation, as did the Indonesians, Malaysians, Indo-Chinese, and other subject peoples. Between 1941 and 1945, the years of American involvement, enormous political as well as technical changes altered the world forever.

NRA Firearms Museum display of American and British arms from WWII.

More than anything else, the Pacific war was a war of logistics. The focus of Western powers on the war in Europe led to an amazing variety of weapons in the Pacific theater. The sheer number of governments involved, and the level of desperation late in 1941, assured a remarkable variety of armaments for the modern researcher to discover. As the war progressed, the impact of logistics was overpowering; Garrisoned stores throughout the theater were swept away by the early Japanese advances. Only the US Navy and Japanese Imperial Navy could move arms and men into battle; all other players were pushed to the sidelines. There was near-total change after 1942. Old World War I weapons inventories swept away by Japanese success were replaced by newly manufactured tools of war, and the overwhelming effectiveness and massive availability of new American equipment after Guadalcanal ensured the decline of British and European influence.

Searching for Reliable History

At this distance in time, the interested student of Pacific war weapons has limited options for truly understanding the war. The region is so vast that a lifetime could be spent exploring the battlefields, and many are accessible only by submarine and helicopter. New governments have arisen, and the ardent researcher is apt to find himself in the middle of a shooting war, if he is not careful. Most of us are limited to researching literature, museum and private collections, and talking to old soldiers. Inexorable demography is reducing the number of veterans able to tell the tale first-hand, and, as one Okinawa veteran put it, you have to decide whether you prefer the “good” story or the “true” one. Private collectors tend to follow a theme to the exclusion of competing points of view, and it’s up to you to sort out the bias, omission, and fact. Museums are little better for reliability, infected as they can be by revisionist, politically active “interpreters.” Equally distressing is the incredible volume of printed material claiming to describe the war in the Pacific, since the paper refuses no ink…

A MAS-38 recovered in the 1960s from the Viet Cong.

Artifacts can speak for themselves, but they are often not allowed to. Recognizing and dealing with revisionist historians is a major problem for the student of Pacific war arms. We must realize that the wonderful Smithsonian collection is lost to us for now, and revisionism, as seen in the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry might lead you to think that the war never happened at all!

A Hotchkiss-derived Benet-Mercier model 1909 in the Marine Air Ground Museum, very similar to the Japanese Model 97.

Three East Coast museums stand out from the politically correct crowd, the Marine Air-Ground Museum at Quantico, Virginia; the NRA National Firearms Museum in Fairfax, Virginia; and the US Army Ordnance Museum at Aberdeen, Maryland. In these repositories of history, you can see and examine unmolested artifacts without the drumbeat of Clinton-era distortion.

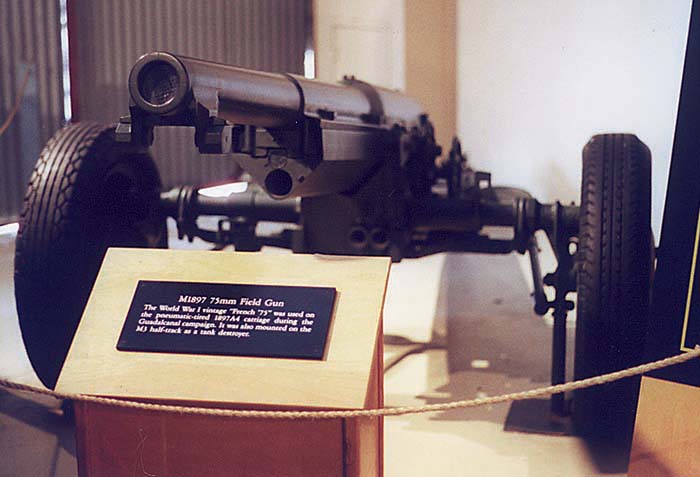

WWI leftover French 75mm Field Gun used during the Guadalcanal campaign.

The Participants, a Thumbnail Sketch

Whole books have been written about each of the weapons, battles and politics of the combatants in the Pacific theater. For perspective, I will only touch upon the equipment of the major participants. All began the war with doctrines and equipment largely left over from the Great War. By late 1942, new American technology began to appear in the field, and new tactics arose to match the “island-hopping” allied strategy for victory. Nearly all of the weapons of late 1941 were passé by the end of the war in 1945. These facts may seem trivial to many readers, but there are now whole generations of Americans, victims of America’s cultural wars, who have not the faintest grasp of who and what were involved in World War II.

Great Britain lost much of her military hardware on the beaches of Dunkirk in the summer of 1940, and she was loathe to share much of what remained with the Far East. With an Army doctrine based on World War I SMLE rifles and Vickers water-cooled machine guns, the British were ill prepared to face the onslaught of their former Japanese allies. A few Brens and Stens went east before December 8, 1941, but most garrisons fought with whatever leftovers they had.. While “British” troops manned twenty-year-old Lewis guns, Indian troops were saddled with inferior weapons like the Vickers-Berthier, and a remarkable quantity of Boys anti-tank rifles found their way to Australia after finding no friends in North Africa. No heavy machine guns and precious little artillery were available

Australia felt abandoned, for good reason, and rushed to produce the inferior Austen and the remarkable Owen submachine guns. “Gangster Guns” had gained acceptance, if not respectability. America, home of the “Chicago Piano,” used the giant island as a huge ammo dump, and American largesse captured the Australian heart. British hardware returned after the crisis passed, but the Australians were never again quite so sure of the British. ’03 Springfields and M1917 Lee Enfields weren’t the cat’s pajamas, but they were very welcome in the dark days of 1942, even if they didn’t share the Empire’s standard .303 ammunition

The Netherlands East Indies met the Japanese invasion with turn-bolt Mannlicher rifles and Schwarzlose machine guns, but too few of either. Sauer pistols and cheap Imperial German surplus items were joined by motley “desperation buys” of United Defense, S&W, Thompson, Mauser, and various sporting guns. It was all too little and too late.

France fought Thailand in 1940 with many of her latest weapons, and modern pieces like the MAS 38 submachine gun would later reappear in the hand of the Viet Cong. Hotchkiss, Chatellerault, and Lebel joined the MAS 36 against the Japanese, but with no more success than against the Germans. Oddly enough, the Chauchat, pressed upon the Americans in 1918 in return for our Marines’ Lewis guns, had disappeared from the French order of battle.

China, dogged by corruption and collapse under foreign intrigue, could field only uncoordinated purchases by independent warlords. A few of everything have been encountered by researchers over the years, but the infatuation with the Mauser broomhandle endured and seemed to be transferred to the Japanese. Several Chinese Mausers appeared on Okinawa late in the war.

Japanese battalion howitzer.

The major combatants, Japan and the United States, entered the war with remarkably parallel doctrines based on massed rifle-armed infantry. The Japanese approach was deeply enmeshed with cultural values, and the tactics and Mauser technology were well proved against the Russians and Chinese. Supported by organic mortar and light artillery, the Japanese soldiers applied an unprecedented confidence that was publicized in the West as the Bushido code and Banzai-fanatic mentality. However, the Japanese war machine was ground slowly under heel by American logistic might and new technology. America’s allies in the Pacific at first received largely obsolete World War I equipment via Lend-Lease. The Japanese army and navy went to war in 1941 with similar 1918 technology. When American 1942 technology arrived en masse, the outcome of the war was only a matter of time and blood.

Detail of a rare S&W carbine.

Obsolete Murata 11mm rifles were replaced by 1941 for the most part by Mauser-style Arisaka 6.5mm and 7.7mm rifles and carbines. Hotchkiss-derived portatives also in 6.5mm and 7.7mm accompanied the troops. Small mortars, common in the Japanese army, amazed the Americans, as did the Japanese cultural dislike of pistols. Similarly, subguns like the SIG-made Bergmann MP18 and the home-grown Type 100 were rarely encountered. The impact of the M-1 Garand rifle cannot be overstated, and the Japanese attempt to copy it has left a few amazing examples for examination.

Detail of the obsolete 1mm Murata rifle.

The American army, after 40 years in garrison as foreign occupiers, was slow to rise from its lethargy. Massive underestimation of Japanese resolve and ability led to enormous losses in the Philippines. Generally equipped with World War I vintage Springfield 1903s and water-cooled Browning M1917 machine guns, the American army had poorly integrated light artillery, and the Browning .50 caliber machine gun remained scarce. The Winchester trench shotgun and Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR M1918) were to become firm favorites of the American infantry, too many of whom would be sacrificed on Bataan. A remarkable collection of miscellaneous weapons had been passed down to the Filipino National Guard units, including trap-door Springfields, .30-40 Krags, Navy Lee rifles, and various Spanish leftovers and hunting guns. All would prove inadequate in 1942.

Water-cooled M1917 Browning with flash hider.

Like the heavy M2 Brownings, the M1 Garands were late in arriving. Once the Army got over its distaste for “ammunition-eaters,” the M1 would join the formerly despised Thompson to transform infantry tactics. Moving ever closer to modern assault-rifle doctrine, the relatively puny M1 carbine and air-cooled Brownings would gain lasting popularity with the troops. Oddly enough, the M3 submachine gun would never engender the affection soldiers and sailors developed for the Tommygun. Like the MAS 38, Thompsons would be found much later in Viet Cong hands, but the M3 was hard even to give away, despite its effectiveness.

More Japanese arms from WWII at the NRA Firearms Museum including an M1Garand copy (top left).

In contrast to the polo club-style army preferred by the MacArthurs, father and son, the US Marines had a peculiar make-do culture developed by years at the end of the budget food-chain. Their innovative use of the BAR and Boys rifle revolutionized amphibious assault, when used in combined arms with amphibious armored vehicles, organic artillery, and novel applications of existing weapons. When supplies of the M1, arguably the best battle rifle in the world in 1941, lagged, the Marines made do with the less desirable Johnson. In addition to Boys rifles “obtained” in Australia, the Marines recreated French .75s and Army pack howitzers for the unique conditions on Guadalcanal. Stung by the failure of the Reising as an assault rifle, the Marines embraced the M1, M1A and the soon-to-be universal squad support air-cooled Browning .30s and .50s as they became available. Both the Marines and the Army rapidly recognized the new need for mortars in terrain and jungles that frequently defeated armor.

Johnson automatic rifle.

Finding History for Yourself

The accompanying photographs show a few of the many surviving publicly accessible artifacts of the Pacific war. Their variety and massive scope are far too great for a mere magazine article, but these collections make for rewarding research opportunities, both formal and casual.

The museums I visited display the guns in glass cases and in the open, allowing close examination. All have curators willing to assist the genuine researcher. All are under relentless cultural attack, and welcome honest students of history and support.

A content Marine with a Savage-built Thompson.

A Marine’s best friend on the road.

A display dedicated to the Boys MKI anti-tank rifle.

A Marine with his M1 Garand and flame thrower.

I alternated visits to the museums with discussions with local veterans. In the Washington, DC area old warriors are a dime a dozen, but the student of the Pacific War must search for Pacific War survivors. Time is rapidly claiming these heroes, so don’t wait to pursue an interest. There were more participants than most Americans realize, and the inexorable loss of first-hand knowledge reinforces the importance of the non-interpreted, genuine artifacts found in these three museums. The veterans can provide true depth to your understanding and illuminate the greatness of the country’s achievement, but don’t delay. I have yet to find a man without a story to tell.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V4N3 (December 2000) |