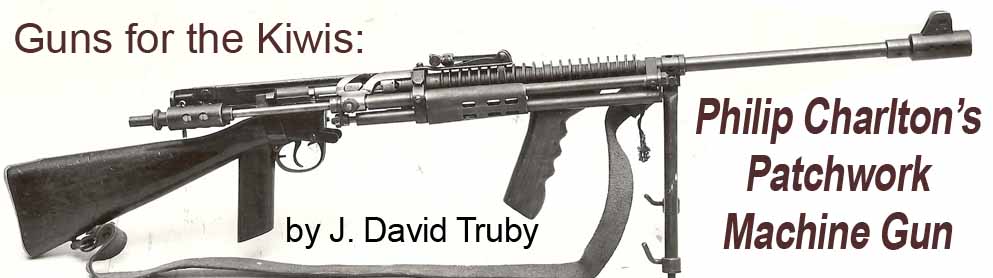

A production run Charlton Gun with strap and bipod. (Jim Crombie)

By late 1941, Japan was rolling to take over the Pacific, preparing to bite down hard on Australia, New Zealand and nibble on other choice morsels of the oceanic lands. Due to Hitler’s stranglehold on the U.K.’s home islands, the lands down under were pretty much on their own for defense.

Like every nation defending against Germany and Japan, New Zealand had a severe shortage of small arms of every kind, but especially semiautomatic rifles and machine guns. In 1941, one interesting theoretical military weapon that stood between the Empire of the Rising Sun land invasion and the Kiwis was Philip Charlton’s theoretical machine gun, theoretically produced from an antique, bolt action rifle.

The Charlton rifle was his conversion of the Lee Enfield rifle of Boer War fame and was intended as a substitute for the Browning, Lewis and Bren machine guns of which Australia and New Zealand had very few, and which England could not supply, according to firearms historian Errol Albert Christ.

Christ notes, “The British had all they could deal with fighting Hitler’s ‘Blizkrieg,’ so that ordnance was not available to supply Australia and New Zealand. Even if the weaponry were available, the supply logistics would have been impossible. Those good folks had to improvise.”

The original Charlton automatic rifles were converted in 1941 from obsolete, bolt action Lee-Metford and Lee Enfield rifles from the Boer War era. Charlton himself referred to the guns as museum pieces in his written proposal to the government. It was to be used as a self-loading infantry rifle with the full-automatic capability available for tactical use. The planned issuance was to the Home Guard. The Charlton fired the .303 British service round, weighed 16 pounds unloaded, was 44.5 inches long, 13.3 inches high and 8.2 inches wide. It was gas operated and could fire approximately 600 rounds per minute.

“I should like to bring to your notice a semiautomatic attachment for service rifle, which I have perfected,” Charlton said when he appeared before the NZ Parliament and the Army to formally present his design in June of 1941. “…The almost complete absence of recoil enables the rifle to be fired from the side through a loop hole. It can be fired at arms length across the body. The attachment is very suitable for anti-aircraft work…” He went on to explain the fully automatic capability, as well

Immediate reaction from the political suits was nervous laughter. How was it possible to make a machine gun from an antique bolt action rifle? He was laughed out of the room, literally, by New Zealand’s prime minister and other parliament members.

However, Charlton was a design genius, had a working prototype, and knew if re-fitted rifles could keep back the horror of the Japanese, the Army was willing to listen and observe. They did so during Charlton’s second demonstration that fall.

According to John C. Osborne, a weapons adviser and researcher at the Queen Elizabeth II Army Memorial Museum in Waiouru, New Zealand, this second application, with a live demonstration, to army officials was conducted successfully in November 1941, with production to begin immediately.

Charlton had an Army contract for converting 1,500 of the Home Guard’s long magazine Lee Metford and long magazine Lee Enfield rifles, which were originally manufactured between 1889 and 1903.

Philip Charlton, who Osborne depicts as “having a very receptive mind and described by fellow engineers as very clever, especially to improving existing mechanical devices,” had actually begun designing weapon conversions before World War II began. He had seen drawings of G.T. Buckham and A.T. Dawson’s work with the Lee-Enfield-type rifle conversion to semiautomatic, but he saw that he could improve on their designs. His resultant selective-fire option worked very well. They looked chaotic and awkward, though, with the conversion kit installed externally. But, the rifle functioned perfectly and safely, according to all accounts.

In the New Zealand version, according to Windsor Jones, curator at the Waiouru National Army Museum, the stock was given a pistol grip and a foregrip, the buttstock was lowered in order to clear the modified action and the rear of the barrel had cooling fins. Charlton modified the sights, and changed the magazine-well to take a modified, larger capacity Lee-Enfield magazine, or a modified Bren magazine. He shortened the fore end so that the barrel could cool more efficiently, and so that the gas operation would fit with the foregrip attached to the gas tube shroud. He tipped the barrel with a muzzle brake and modified the barrel length. Also, unlike small arms of that era, this patchwork weapon was adapted to use a clip-on bipod for full auto fire stability.

Of course, all this had not come together to work on his first try. But, Charlton never let failure get in the way of his dream. One malfunction after another didn’t stop him from creating his gun that would do the job. According to Osborne, “Philip always discussed these problems with as many people as possible. He was determined to make the conversion work and, asking as many other knowledgeable engineers and gun aficionados for ideas as he could, proved to be successful. His final, patented design worked perfectly.”

Born in 1901, in Grimsby, Lincolnshire, England, Philip Charlton, an engineer by education and training, was destined to become a firearms design expert, according to period newspaper stories plus family member stories about him. He got his first .22 rifle, a B.S.A., for his 14th birthday. His love of firearms, along with countless hours of target practice with other gun buffs, plus his keen engineering mind prepared him for the work needed to develop his emergency rifle that would keep the Japanese at bay if they ever attacked New Zealand.

Charlton’s nephew, John P. Charlton, remembered that his uncle was passionate about intricate mechanical workings of all kinds. “When I knew him, he owned a Mk2 Jaguar, which he thought was one of the best cars in the world. He took me to the Auckland War Memorial Museum to see a Rolls Royce Merlin engine there – he said it was the finest internal combustion engine ever made.”

It was only natural for Charlton to speak with equal exuberance about car engines as he did about the machinations of guns, because he became a qualified automotive and general engineer before he arrived in New Zealand from England in 1923. His granddaughter, Liz Whiting, says he traveled from England to New Zealand as the ship’s engineer and radio operator on the Grimsby Steam Trawler. She said he was “quite relieved to reach NZ safely as the only training he had as a ship’s engineer and radio operator were what he had read in the local library several days before departure.”

Once in New Zealand, he set up his own business in Hastings as an automotive motor body engineer, according to his nephew. It was in Hastings that Charlton’s intense interest in all aspects of rifles grew, and he first suggested his idea to convert a self-loading rifle to a fully automatic gun to his friend and fellow gun fancier, Maurice Field. That idea grew into the prototype of The Charlton Automatic Rifle.

Two versions of the Charlton existed: the New Zealand version produced locally by Charlton Motor Workshops in Hastings, and a version made in Australia by Electrolux, using the SMLE Mk III for conversion. The two designs differed greatly in external appearance, as the New Zealand Charlton had a forward pistol grip and a bipod and the Australian version didn’t. However, they used the same operating mechanism.

John Osborne reported that Charlton negotiated with the Australian government in 1942, to provide 10,000 Charlton automatic rifles similar to those being produced in New Zealand, to be made in Australia. Osborne wrote, “Phil Charlton entered the factory (one morning) very excited, waving a telegram requesting that he go to Australia the next morning.” Charlton received a small royalty for each completed rifle, which was somewhat less than the royalties he was to receive from the New Zealand government.

In anticipation of the Japanese invasion of New Zealand in 1942, about 1,500 rifles were manufactured in New Zealand, while only a few prototypes were turned out in Australia, according to firearms researcher Ian Skennerton.

The Charlton Gun was not his only contribution to wartime armament. He continued scheming ways to fight against the Japanese threat, with some personal risks.

“Uncle Phil went on in the war to develop a ship-mounted anti-aircraft gun, which, unfortunately, jammed during testing,” John Charlton said. “By bypassing some of the electrical interlocks he managed to get it to fire. But unfortunately, those interlocks had disabled the gun because of a fault and it exploded, badly damaging one of his hands. The doctors wanted to amputate two fingers, but he wouldn’t let them. He regained most of the movement in them eventually, which didn’t surprise me at all.”

Happily, even through all of Philip Charlton’s innovation, sacrifice and toil, the dreaded Japanese invasion never came. Thanks to superior air and sea power, plus resupply capability, the Allies stopped the Japanese advance, and slowly turned the war from one of defense to a highly potent offense. Thus, WWII ended with none of the Charlton rifles ever seeing combat.

His granddaughter says that after the war, Philip Charlton ran an automobile parts distributorship, plus designing a hydrogas system to supply automobile power, and a system to micro-open pistons. He and his wife, Eileen, raised two children, Robert and Faye. Philip Charlton died in Auckland Hospital in 1978.

Sadly, most all of the Charlton inventory was destroyed in an accidental fire at the Palmerston North Armory storage facility shortly after World War II. According to Osborn, less than 200 survived the fire, and were used for training and demonstration purposes. These deteriorated through time and were scrapped, a tragedy for historians and collectors. Today, only a handful of the converted rifles survive as Philips Charlton’s legacy.

Where are those remaining rare legacies of Philip Charlton’s true small arms innovation and national significance? There are only five which exist officially, and they are housed in museums: The Waiouru Army Museum in New Zealand; The Museum of New Zealand (Te Papa); The Auckland Museum; The Army Museum (Bandiana) in Australia; and The Imperial War Museum in London. A few others are thought to be in private collections, unofficially or otherwise. Or, as a youngster, John Charlton remembers that years ago, his Uncle Phil used to keep “a couple or so in his back shed.”

(Many thanks to the following who provided valuable research and assistance about this little known man and his unique machine gun design: Ralph Behrends, Curator of the Army Museum, Bandiana, Australia; John Charlton, Philip Charlton’s nephew; Errol Albert Christ, firearms historian; Albert R. Christ; Marian Fiscus; Michael Fitzgerald, Director of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa; Windsor Jones, Curator of the National Army Museum of New Zealand; Kari Randall; Dan Shea; Elizabeth Whiting, Philip Charlton’s granddaughter; and Paul Wraight, photography and Jim Crombie.)

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V15N2 (November 2011) |