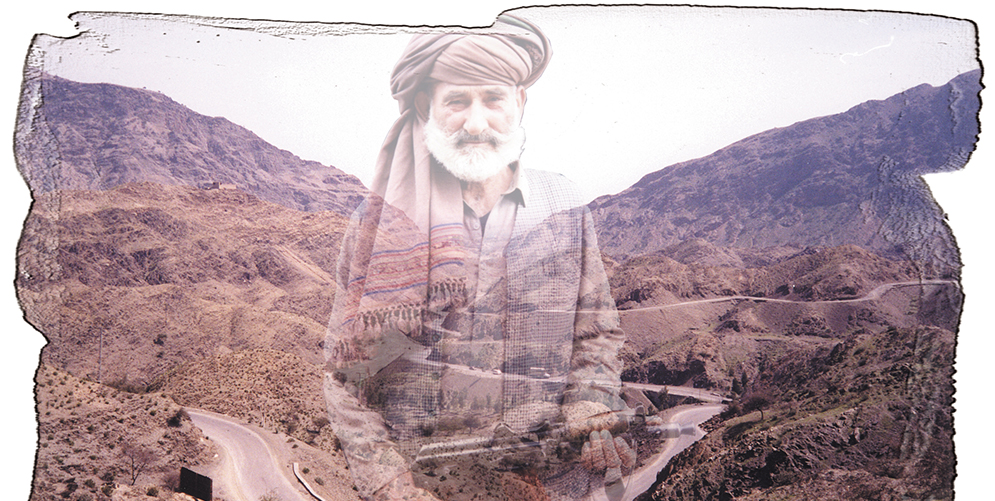

A Pathan elder holds his Krinkov with the tortuous switchbacks of the Khyber Pass in the background.

By Rob Krott

One particularly deep pothole lifted me several inches off the seat as the Toyota Landcruiser bounced up the road. My head snapped up, waking me from a doze only to see the barrel of a Kalashnikov assault rifle wavering about six inches below my chin. The Afridi tribesman, a pimply faced youth, sitting next to me and clutching the rifle seemed unconcerned. I looked at the selector lever and noticed the weapon was loaded and on “automatic.” In the crowded car every bump had the potential to send bullets flying. I smiled at the youth (who nodded happily at me) and then I gently moved the barrel away from my face and reached down to place the weapon on “safe.” My friend, Muhammad Sultan, an Afghan refugee and de-mining expert, sitting on the other side of our gunman noticed my actions. Sultan said, “Not to worry, Rob! The soldiers must account for every bullet that is fired.” Our driver bobbed his head and intoned, “Inshallah!” Ah, yes, “Inshallah.” Welcome to the Khyber Pass.

The Khyber Pass is the territory of the Afridi, the Pathan tribe that has controlled the Khyber for centuries. It is a region lost in time with adobe-mud fortresses dominating the landscape, women in colorful burqqas, and mustachioed rifle-toting brigands wearing turbans. I couldn’t wait to see it.

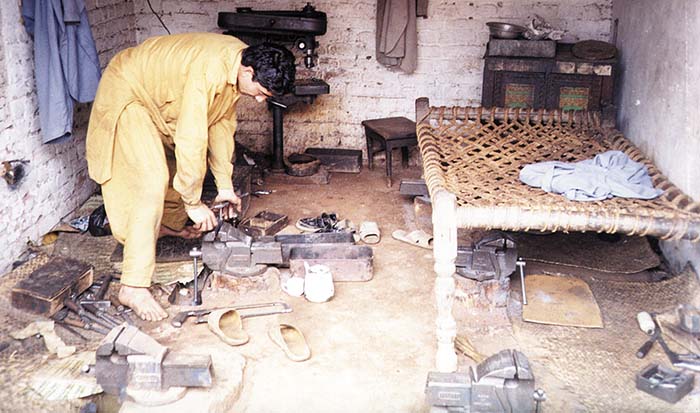

It has been called the oldest continuously lawless place on earth. The nearly autonomous tribal enclave here was first “administered” by the British who found it impossible to subdue the warlike Pathans, said to be the world’s largest autonomous tribal group, and established the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) in 1901. Pakistani national and provincial laws hold little sway here: tribal lands are actually ruled by the Pathans through their council of tribal elders, the jirga. Pukhtunwali – an unwritten code of revenge and blood feuds against enemies, refuge for friends and kinsmen, and hospitality for strangers (badal, nanwatai, and malmastia) — is the law. The Pathans run guns, smuggle consumer goods, and increasingly, opium. Large tracts of opium are cultivated here and hashish and, more recently, heroin are major commodities. The Shinwari tribe operated heroin labs in hidden caves in the mountains near the Khyber Pass until government pressure made them move west into Afghanistan. During the war against the Soviets the mujahideen smuggled opium to swap for guns and in doing so invigorated the opium production in Pakistan.

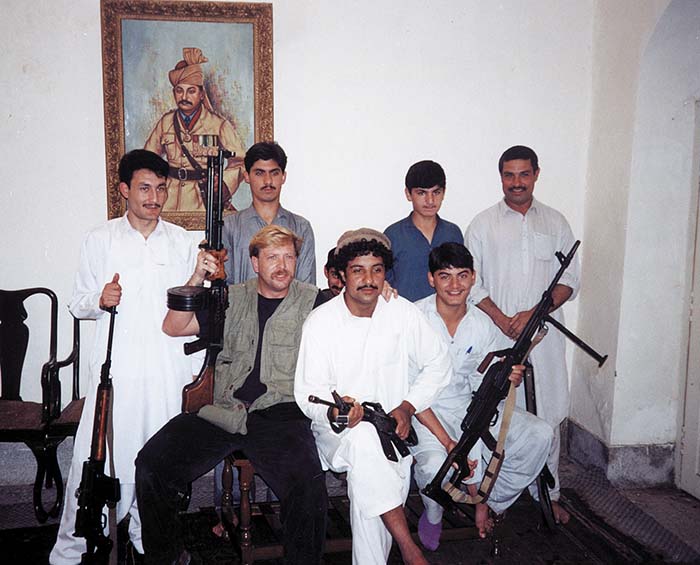

Hard lands make for hard men and barren mountains and bleak winters have made the Pathans a hardy breed. Fiercely independent, the Pathans consider guns necessary accouterments and maintain large private arsenals to defend their family compounds during frequent clan disputes and from attack by dacoits – bandits. With shootouts; armed robberies; bombings; kidnapping; fights over livestock, slights to their womenfolk, personal insults, and generations-long blood feuds; and just good old fashioned violence, the tribal lands resemble the American wild west. Everyone carries a firearm. Consequently, people are polite. Justice is swift and bloody.

Pathans, also called Pukhtuns, have over the past two decades attempted to create an independent country, Pukhtunistan, encompassing the tribal lands, which straddle the border and the approximately 12 million Pathans (60% of the tribal population) living in Afghanistan. With fair skin, high foreheads, straight noses, and light hazel eyes, the Pathans look European. There’s the theory that this is because Alexander’s legions swam in the local gene pool c. 336 B.C. while others believe that some of the Aryans stopped here enroute from Europe when they invaded the Indus c. 1600-1500 B.C. Pathan tradition holds that they are descended from King Afghana, grandson of King Saul of Israel. Whatever the source of their genes, they certainly don’t look at all like Punjabis or Sindhis. What they do look like is “tough.”

The day I arrived in Pakistan I checked into the Pearl Continental Hotel. A sign in the lobby said, “Weapons cannot be brought inside the hotel premises. Personal Guards or Gunmen are required to deposit their weapons with the Hotel Security.” Next stop was the Pakistani Khyber Political Agent’s office for my Khyber Pass travel permit. I was directed to a cramped office, piled high with dusty ledgers, which appeared unchanged since the 19th century British colonial administration. Even the electric fan was pre-World War II. Three clerks sat around desks piled high with papers while shelves and bureau tops along the dirty, whitewashed walls held precariously balanced ceiling high stacks of old cloth-bound ledgers and loose-leaf files shedding papers. The ever-present battered teapot and glasses crowded a small table. I was half expecting some one to blow a great cloud of dust off one of the ledgers and say “Mr. Robert! Yes, you still owe mess dues from 1919 … or was that your grandfather?”

The major route connecting Peshawar with Kabul is traversed via a tough, twisting drive up the Khyber Pass past Landi Kotal to the border post at Torkham. This area is considered dangerous and I had to pay a nominal fee for my travel permit and for my Khyber Rifles escort. After receiving my pass I waited around a few minutes for my Afridi gunman, a member of the Khyber levies, dressed in a black beret and a gray kurta and shalwar kameez (a knee-length cotton shirt over pajama trousers). A short, pimply-faced kid clutching a Kalashnikov, he made a pitiful looking bodyguard.

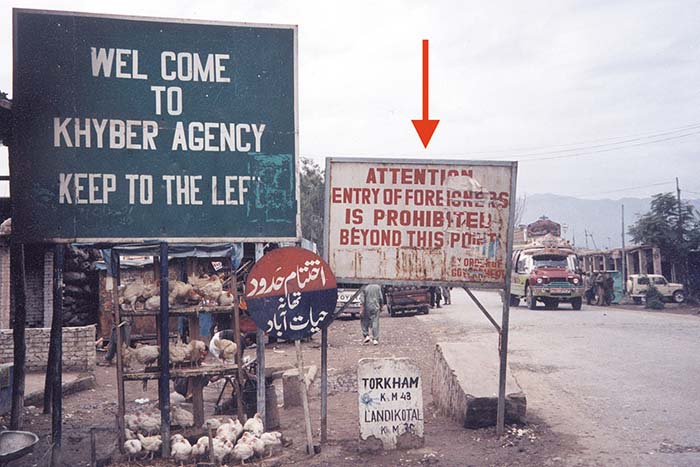

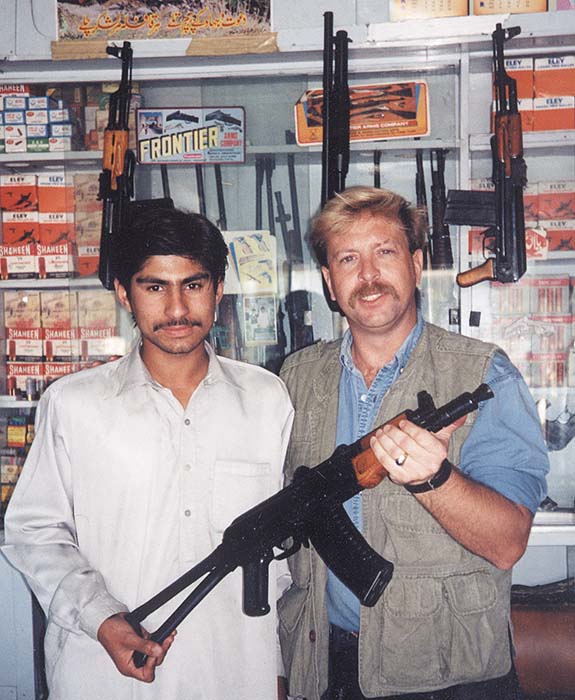

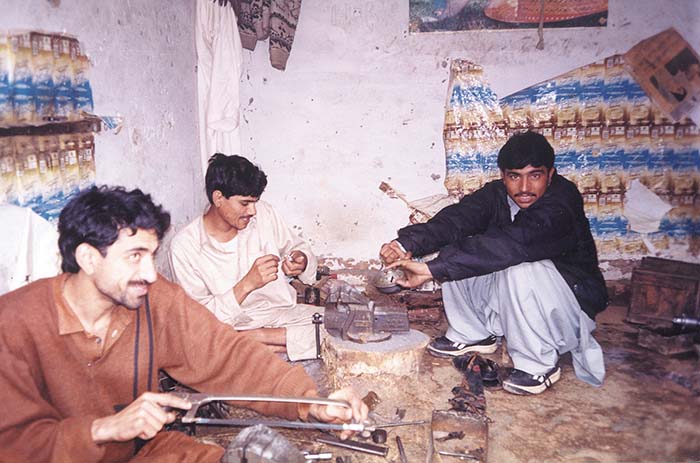

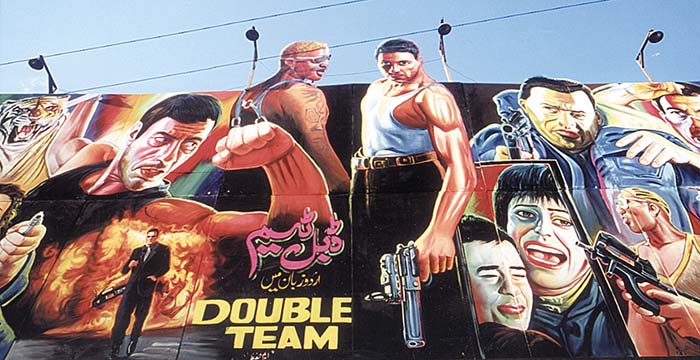

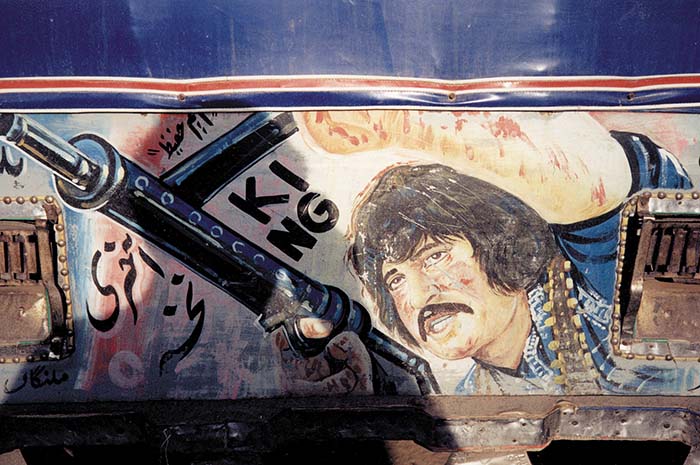

The drive through noisy, bustling and completely third-world Peshawar to the Khyber Agency is itself an interesting journey. Dominating the skyline lurid billboards of burly matinee idols angrily spewing hot lead from automatic weapons advertise ultra-violent Pakistani and Indian movies. Similar Rambo-esque paintings adorn buses and the three-wheeled Vespa taxis which always seem to be on the verge of imminent collision. We passed the gun shops of Peshawar: small one room shops holding a few dozen weapons and adorned with names such as Frontier Arms, Haji Farhad & Bros. Arms and Ammunition Dealers, or Bashir Ahmad Co. The weapons for sale are sometimes comically counterfeited, including a copy of a Russian submachine gun stamped Special Rolex. Next we drove past Karkhanai, the new smugglers’ bazaar where there are no longer drugs or guns for sale (that was all stopped a few years ago) and drove through the police checkpoint noted for its “Attention Entry Of Foreigners Is Prohibited Beyond This Point” sign. I was no longer under official Pakistani government control. This was Afridi tribal territory, the Pathan tribe that has controlled trade and travel through the Khyber for centuries. Here, just beyond the checkpoint you can buy guns and hashish. I stopped at some gun shops only to be rushed off by the police.

The world beyond the checkpoint is like something out of The Road Warrior. The adobe mud fortresses — guard towers and walls stand 20 feet high with embrasures at the corners so sharpshooters can engage interlopers — dot the landscape. There are no windows, just gun ports and loopholes, and the only entrance is a 20-to-30-foot-high steel gate. Everyone is armed. The whole area is built for tribal warfare. As we drove by I caught forbidden glimpses inside the compounds of beautiful gardens and landscaped courtyards.

The army checked my travel permit at Jamrud Fort. Built by Sikhs in 1923 it is only eleven miles and two centuries from Peshawar. The formal entrance of the pass is the stone arch built in 1964 by military decree as a kind of tourist attraction. My ride was a red Ford minivan (a bargain at less than $20 a day). While stopped at the Khyber Pass archway people began scurrying for cover as bullets flew just up the road. A little inter-clan flare up or blood feud was in full swing. The police ran over to tell us to stay where we were. My Khyber Rifles escort began to look worried. The red minivan, which looked so sharp before now, made a very good target. After about half an hour we were waved on up the pass. The east end of the pass road winds through a wide, flat plain marked by low hills on both sides. Throughout the valley were rows of WWII “dragons teeth” concrete tank obstacles. The road then climbs up through the Suleiman Hills rising up on both sides of the pass to Shagai Fort.

Coming down the mountain were several bicycle riders with one or two other bicycles in trail. They were smuggling them over the mountains from China via Kabul. A tough way to make a living. As camel caravans moved across the mountaintops, Afridi women in their brightly colored burqqas walked languorously along the pass road. Carting bundles of freshly cut grass for their livestock they form small knots of blue, orange, red, and gold against the Khyber’s blue-green mountains standing silent beneath a bright blue sky dotted with powder puff clouds. In the foreground of this picturesque scene was the crumbling adobe of the mud walled forts. Hugging the cliff walls and occasionally crossing the roadway is the Kabar railway. Built by the British in the 1920s it is forty-two kilometers long with 34 tunnels and 92 bridges. Some of the trestles looked shaky and in places the track hung precariously off the mountainside. There were spots where there was nothing underneath the tracks but mountain air.

The narrow point of the Khyber Pass is at Ali Masjid. Above the Ali Masjid mosque sits the Ali Masjid fort which overlooks the entire Khyber Pass. Here the road is one way as it’s only thirty meters or so wide. Before it was widened two camels could not walk abreast. To fully appreciate the Khyber Pass you must imagine trying to escape through the pass on foot while being shot at by Pathan snipers. Testifying to the near impossibility of such a feat, is a British cemetery full of graves from the Second Afghan War of 1879. The Khyber Pass walls bear the insignia of many British regiments, such as the Royal Sussex, the Gordon Highlanders, and the South Wales Borderers, to name but a few. Mute testimony to the far-flung reaches of a vanished empire, they reminded me of the arrogance of Daniel Dravot and Peachey Carnehan in Kipling’s The Man Who Would be King. Ten kilometers further is the Buddhist stupa from Kushen times. Another seven kilometers along the road at 1,200 meters in elevation and sitting at the end of the railway and just eight kilometers from Afghanistan is Landi Kotal.

Formerly “contraband city” full of hash and guns for sale and the plush homes of rich smugglers hidden behind compound walls, the smuggler’s trade has now moved to the Karkhanai Bazaar near Peshawar. But I’ve been warned: kidnapping for ransom is a frequent event and the locals certainly aren’t too timid to avoid mugging a westerner. Landi Kotal is a notorious den of thieves, smugglers, bandits, and kidnappers. In other words, a nice place to have lunch.

With the smells of sizzling meats on charcoal braziers enticing us we stopped to lounge on charpoy (bedsteads of woven straw and nylon cord) on a balcony above the main street of Landi Kotal. I stuffed myself with chabli kebab (hamburger), tikka – spiced grilled meats, nan, the circular flat roti of the country, slapped from dough in the palms and cooked in the tandoor, all washed down with glasses of chal sabaz (green tea). When it comes to my stomach I’m fluent in Pashto.

I wondered through a bazaar and a group of four or five young women passed me. With their colorful flowing burqqas and their clanking jewelry, their expressive almond-shaped eyes — the amber, hazel, and light gray of Alexander’s legions edged with kohl — flashed promises at me. It was all so amazingly enticing and seductive. I was strangely titillated by their unspoken lust communicated by a single glance.

After Landi Kotal the road forks: left to the Afghan border and right to Khyber Rifles headquarters. Bearing left it didn’t take long before we crested the last hill at Michni checkpoint to see the border post at Torkham. Beyond that lies Afghanistan. Unless you have a special pass and an Afghan visa this is the last stop — fifty-eight kilometers from Peshawar.

It was turn-around time and the trip back was as breathtaking and adventurous as the trip to Michni. I spent a few days in Peshawar and Nooristan and then made my second trip into the Khyber and journeyed on to Afghanistan. We passed through Landi Kotal and the Michni checkpoint again before descending the last few kilometers to the border post of Torkham. The whole scene was a Kodak moment but photography is prohibited. The Khyber Rifles soldiers clad in the traditional pajama-like shalwar kameez and commando sweaters stood at the ready with their assault rifles. They passed us through to Afghanistan with a nod to be greeted by Kalashnikov toting Taliban. After we crossed the border a brief shootout commenced between the Khyber Rifles and the Taliban as someone ran the border and the Khyber Rifles opened up. A vehicle which came through only a few minutes behind us took a bullet in its left side rear door.

After a week in Afghanistan it was time to go back to Peshawar. Just as well. I was sick and no amount of Lomotil or Cipro seemed to help. As we approach the border post the scene was right out of the middle ages and the Black Death. Everyone was filthy and dressed in rags and blankets. The dirt road was ankle deep in fecal muck. People aged long before their time by hard labor, squalor, filth, disease plod through the mud while small boys, dirt-faced, snot-nosed carbuncled urchins trotted along with loads of scrap metal on their backs like under-fed pack animals. Scrawny horses pulled wagons, their wooden wheels clacking and slurping in the mud. I solemnly intoned “Bring out your dead!” a line from Monty Python and The Holy Grail — what I was seeing is so reminiscent of that movie scene that the other American with me chuckled. Crossing the border I turned my watch back a half an hour. Afghanistan is half an hour ahead of Pakistani time and five centuries behind the rest of the world. Indeed the Afghans claim it is year 1376 as calculated from the moon phases.

I stopped at Afghan Emigration — a mud hut with a rickety table and two bored Taliban with moldy blankets over their shoulders. I got my passport stamped and was through the border. Next was Pakistani Immigration and then customs. There’s no problem with my visa even though it quite plainly states “single entry.” On the way out the frantic, chaotic coming and going of people was unbelievable. Walking out of customs I was almost run down by five or six boys with loads perched on their backs dodging like half-backs as they tried to avoid a Pakistani Khyber Rifle trooper flailing away with his swagger stick. He wasn’t trying to stop them or arrest them, just giving them a beating. “Oh my what fun, yes, very good!”

The drive back to Peshawar was uneventful except for that slight problem with the ever-present Kalashnikov barrel under my chin. Amongst the Afridi a common family occupation is smuggling and at the various Khyber Rifles check points I looked up on the hillside to see smugglers walking the parallel mountain trails in plain view. On the way back just before the last police post we saw the smugglers, all gathered to begin their run over the mountains at 3:30pm (the police go off at 4pm) humping stereos, dishware sets, and car parts over the mountains and into the market. Dodging the battered trucks and buses belching noxious plumes of blue gray smoke and loaded down on their springs with human cargo and careening up and down the narrow macadam highway we soon arrived back in Peshawar. I checked in to Green’s Hotel. It’s at the bottom of the list for western-style accommodations — the decrepit rooms had moldy walls and peeling paint while the restaurant’s table cloth were stained with the detritus of a decade of meals. It was probably a very nice hotel at one time but today it’s just another remnant of the fading splendor of the Raj era. But after the Khyber Pass it certainly looked like the 20th Century.

Rob Krott made four separate trips into the Khyber Pass and crossed the Pakistani border three times on a single entry visa. Rob, a professional war correspondent since 1992, currently travels for the TV show The World’s Most Dangerous Places which can be seen on the Travel Channel.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V4N7 (April 2001) |