By Robert Bruce

“The average adult male in Sough Vietnam is about 5 feet, 2 inches tall and weighs about 105 pounds. Accordingly, he finds some difficulty in using many items of American equipment. The standard United States rifle is too long; the Browning Automatic Rifle is too heavy; and American parachutes are too large, causing the light-weight jumpers to descend slowly and be scattered over wide areas on landing.” From U.S. Army Area Handbook for Vietnam, 1962

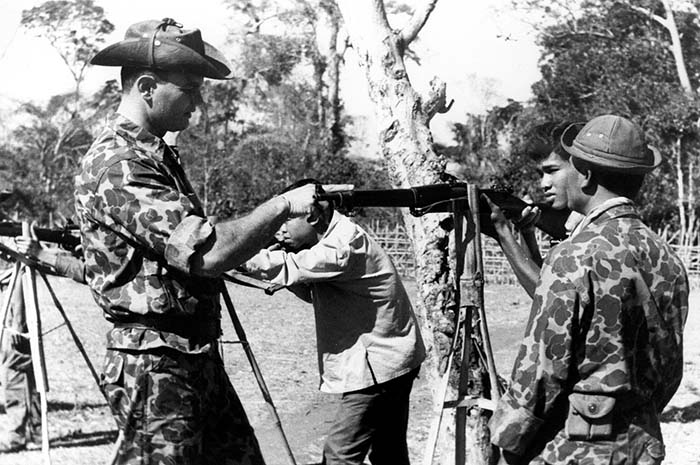

Credit: US Army Military History Institute/Robert Bruce

When France finally raised the white flag of surrender in July of 1954, America already had long maintained an active presence in Vietnam. From OSS operatives during WWII to observers, liaison officers and aid workers thereafter, the United States had numerous personnel actively helping the war effort and many of these were also reporting back to Washington. This began increasing dramatically in September 1950 when the first large contingent of MAAG Indochina — the Military Assistance and Advisory Group – arrived in Saigon.

MAAG personnel had watched with growing frustration as the French repeatedly squandered just about every tactical opportunity and logistical advantage afforded them. Several high-ranking American military officers had made in-depth inspections of the situation and were not impressed.

In particular, the crusty and no-nonsense Marine Corps Major General Graves Erskine had minced no words during a fact-finding trip in July 1950. “The French haven’t won a war since Napoleon so why listen to a bunch of second raters when they are losing this war,” he reportedly told U.S. Minister Donald Heath.

Sure enough, scarcely four years later the French had, indeed, lost another one and the time had come for America to put up or shut up in South Vietnam lest it too should fall to the communists. President Dwight Eisenhower, who had distinguished himself as Supreme Allied Commander in Europe during WWII and had watched the Korean War end in bitter stalemate, wasn’t about to let this happen.

America to the Rescue

What should have been a small bright spot in an otherwise dismal situation was that there were a lot of brand new American weapons and shiny fresh ammo sitting in warehouses, depots and bunkers all over South Vietnam. It seems that the French, frantically demanding and getting more and more armaments as their military fortunes steadily declined, hadn’t been able to move the stuff out to the field fast enough.

From .45 pistols and Thompson submachine guns to .50 cal Brownings, mortars, artillery, aircraft engines, trucks, tanks, and everything in between, hundreds of millions of dollars worth of the tools of American style warfare were there in abundance. Unfortunately for the fledgling South Vietnamese military, the French took advantage of nearly a year between their capitulation and withdrawal to loot the best of this and cart it off for use in their growing Algerian crisis. What was left, according to US Army documents of the time, were huge amounts of deteriorating and inoperable equipment.

Credit: US Army Military History Institute/Robert Bruce

Making the best of a raw deal, it remained for General J. Lawton Collins, the US Army’s newest top man in Vietnam, to put the best of the worst into the hands of France’s intentionally-slighted former subjects. But first, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam – ARVN – would have to be trimmed to a manageable size and structure.

“By mid-November [1954] Collins had drawn up a proposal to form a smaller but well-equipped and well-trained army. Under its terms, the existing force of about 170,000 men was to be reduced by July 1955, to some 77,000. Entirely under Vietnamese command and control, the revamped army was to have 6 divisions – 3 full field divisions capable of at least delaying an invasion from North Vietnam and 3 territorial divisions…to provide internal security and, if necessary, reinforce the field divisions.” From Advice and Support: The Early Years

Even at the modest level of 77,000 regulars (later boosted considerably), the task of arming and training so many officers and men was daunting. Army Colonel Charles Askins, known to many even today as a near-legendary competitive marksman, big game hunter and gun sports writer, served on one of the early advisory teams in Vietnam. Like Marine Major General Erskine, Askins wasn’t impressed with what he found on arrival in 1956 and pungently commented on the situation in his autobiography.

“The French had occupied the country for three-quarters of a century and not only had no ranges for the Vietnamese but had no place for their own troops to do firings. Neither small arms nor artillery. No wonder they couldn’t whip the Viet Minh!” From Unrepentant Sinner

Colonel Askins applied himself to fixing the problem with characteristic energy and invention. He soon had a serviceable facsimile of a classical US Army range with movable target frames and firing points at 100, 200 and 300 meters. Then, he ran a large group of Vietnamese infantrymen armed with .30-06 cal. M1 rifles through a basic qualification course but came up with disappointing results – particularly in offhand (standing, unsupported) shooting.

While knowing that the 9.5-pound Garand itself was too heavy for these little soldiers, he theorized that part of the problem must be that the rifle’s stock was too long. Accordingly, he had a couple of inches lopped off and ran the tests again; only to find no significant difference between the scores of those shooting standard rifles vs. others with short stocks. The real problem, Askins learned, was that “none of them could shoot. I was told during the course of training that it wasn’t the bullet that counted – it was the noise. What can you do with people like that?”

People Like That

“In antiguerrilla warfare, trained soldiers under capable leadership have displayed excellent combat discipline. American advisers generally regard the troops with whom they are associated as being effective, trustworthy and courageous under fire. There have been instances of abandonment of equipment and heavy losses through surrender….” From U.S. Army Area Handbook for Vietnam, 1962

Credit: US Army/National Archives/Robert Bruce

From the beginning, nearly all American weapons and doctrinal employment of them were a poor fit for the average South Vietnamese soldier whose unsophisticated agrarian aptitudes and small physical stature presented significant obstacles for even the most patient and determined trainers and advisors. This is not their fault; it’s just the way things were.

Reviewing the standard lineup of infantry small arms as listed in Army ordnance catalogs of the late 50’s and early 60’s we find such classic weapons as the .45 ACP M1911A1 auto pistol with its energetic recoil and a grip surface requiring a big hand for effective aiming and control. The Thompson submachine gun weighs in at around 9 pounds loaded yet offers little more than the pistol in range and penetration. Ditto the M3 “Grease Gun.”

The Browning Auto Rifle, one of the most reliable, accurate and effective infantry combat weapons of World Wars I and II, tips the scales at more than 20 pounds and stretches out to nearly four feet in length. Even worse, the .30 cal. Browning air cooled M1919A6 “light” machine gun, a mainstay of the US Army in Korea, is a hefty 32.5 pounds and just one 250 round can of metallic-linked ammo adds another 20 lbs.

Years later, issue of the 9 pound lighter 7.62mm M60 machine gun to ARVN units was a welcome development, but one may speculate that belt-fed 5.56mm Stoners would have been a much better fix.

Only the little M1 carbine seemed to be a suitable weapon, with loaded weight of about 6 pounds and overall length of just under 36 inches. Indeed, this fast-firing, low recoil mini-rifle can be seen in innumerable photos of South Vietnamese troops in all sorts of situations during the 1950’s and early 60’s. And, it looks just perfectly scaled for the short, lean Vietnamese.

Unfortunately, the carbine was chambered for a glorified pistol round and wasn’t much in the range, lethality and foliage penetration categories; critical factors for combat effectiveness. Worse, it was even less reliable in the tropical climate of Vietnam than it had been in Korea where its reputation was lower than dirt. Compounding the problem was the native troops’ often-casual attitude toward preventative maintenance. This was bad enough with stalwart arms like the Garand or BAR, but particularly inexcusable with the temperamental selective fire M2 version carbine.

ArmaLite to the Rescue

As luck would have it, the solution to this small arms dilemma was slowly making its way through multiple bureaucratic obstacles. The ArmaLite AR-15, a 5.56mm version of Eugene Stoner’s brilliant NATO caliber AR-10, had first been put into a limited production run at Colt’s back in late 1961. Bobby Macdonald, a particularly energetic field rep, had arranged for ten rifles to be sent to Saigon for testing by the Vietnamese and their American advisors. Not surprisingly, nearly everybody who got to shoot these fast-firing and highly controllable little assault rifles was reported to be favorably impressed. This led to a more formalized evaluation both stateside and in combat in Vietnam that drew similar conclusions.

Credit: US Army/National Archives/Robert Bruce

“The suitability of the AR-15 as the basic shoulder weapon of the Vietnamese has been established. For the type of conflict now occurring in Vietnam, the weapon was also found by its users and by MAAG advisors to be superior in virtually all respects to the M1 rifle, M1 and M2 Carbines, Thompson Sub-Machine Gun, and Browning Automatic Rifle.” Advanced Research Projects Agency Report of Task 13A (From The Black Rifle)

Unfortunately for the ARVN, they would have to wait several more years before most South Vietnamese units – understandably last in line behind the US Armed Forces who were soon doing most of the fighting – would get enough “black rifles” to go around. Sorry ‘bout that.

Primary References:

US Army Area Handbook for Vietnam, 1962

Advice and Support: The Early Years, US Army Center of Military History, 1983

Unrepentant Sinner: The Autobiography of Col. Charles Askins, Paladin Press, 1985

The Black Rifle: M16 Retrospective, Collector Grade Pubs, 1987

Small Arms Identification and Operation Guide, Defense Intelligence Agency, 1976

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V5N7 (April 2002) |