By Richard MacLean

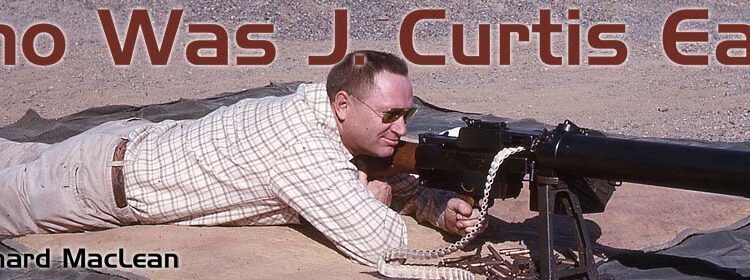

Some claim he was one of the most important figures in the Class 3 firearms world, a courageous individual who was willing to take on the ATF, a major benefactor of the NRA, the founder of a world-class arms museum and a mentor to many. Others viewed him as an abrasive, tightfisted, petty man, ready to challenge family, friends and customers alike at the slightest perceived wrongdoing. Indeed, he was all these things and much more. This article sheds light on the life of this complex individual through whose hands thousands of machine guns passed… maybe even one of yours.

Small Arms Review has published many articles about famous figures in the gun world. For these luminaries, the focus was on the chronology of their business dealings in developing the gun industry as it exists today. Each contained a brief outline of their lives with little mention of their personal affairs. They are famous and respected for what they did, invented or created.

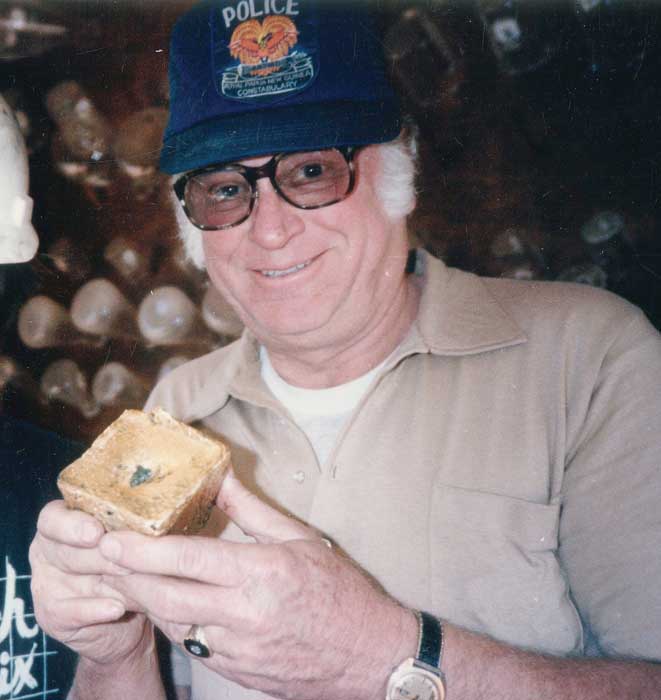

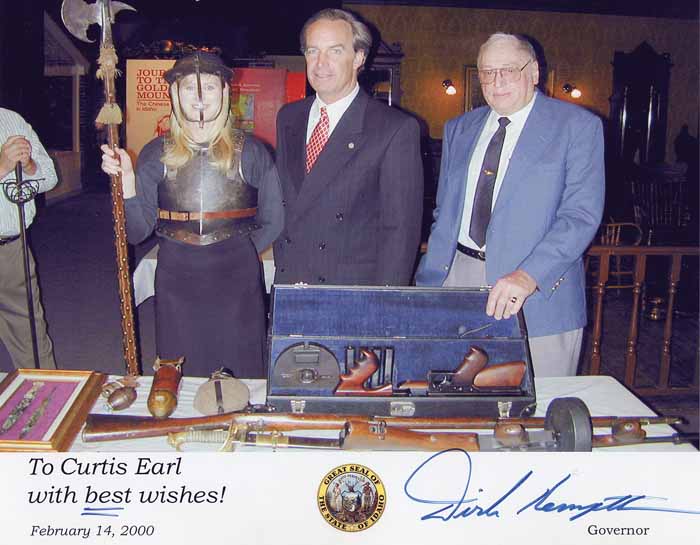

J Curtis Earl was famous as an early and influential Class 3 dealer who amassed one of the largest private gun collections in the world. But he was legendary for his abrasive personality and sometimes questionable business practices. At the time of J Curtis Earl’s death on July 19, 2000, he had amassed a throng of embittered individuals to whom the mere mention of his name would prompt scornful, disparaging remarks.

His passing was reported in Volume 4, Number 4, January 2001 issue of Small Arms Review with a brief, factual summary of his life and a description of the infamous ATF raid and his Senate testimony. Back then, sensitivities about Curtis Earl were still raw and the timing was not appropriate to go into much more detail. Even today, a few reacted bitterly when asked to recall events about Curtis for this article. They responded, in effect, “Why should I help promote his fame?”

We are neither attempting to build his fame, nor are we doing a character assassination. Nearly a decade later, it is possible to step back and objectively describe the man, both the positives and the negatives. This three-part article lays out the facts, and the readers can make their own determination as to who J Curtis Earl was. There are thousands in the gun world who have had personal interactions or business dealings with him. Were their experiences consistent with the others who dealt with him? Were their experiences unique? This article may bring closure to these and many other questions. Plus, to those unfamiliar with the man, it will most assuredly be a fascinating journey.

This first part describes his well-known personality characteristics and the early events in his life that shaped the man. Part two, in an upcoming issue, will outline his business strategy and a detailed description of his breathtaking inventory of NFA weapons. Part three will describe his growing isolation from the gun community and his quest for a lasting legacy.

A unique aspect of each part is the inclusion of detailed information and photographs of his personal life. Yes, as in past articles, we describe his specific business dealings and the famous guns he owned, but if this were all that we portrayed, we would provide no insight into the man himself. And this narrative is as much about the man as it is in how he made millions as an early Class 3 gun dealer.

This article is the result of the integration of scores of sources; most of the information is revealed here for the first time anywhere. Surprisingly, relatively little hard documentation exists on J Curtis Earl. Rumors and stories abound, however. For example, he was believed to have equipped his AT-6 aircraft military trainer with machine guns. Not true, but this rumor provides a perspective of just how odd the stories are that evolved. Separating fact from fiction was our primary goal. Again, we want to present the available information to readers so they can make their own assessment.

Primacy was given to public records such as Senate testimony, census, birth, marriage and trust records. Family members were interviewed and a draft of this article was reviewed by his daughters, first wife and several of his grandchildren. Their recollections are considered true and accurate: they were there, as it were, at the time of certain events. First-person descriptions of events from friends are considered accurate to the extent that they describe the actual events that they observed. A few events directly observed by reliable individuals were not included since they were, frankly, too controversial and potentially upsetting to the family.

A number of direct conversations between Curtis Earl and others are repeated and these are considered accurate in so far as the story told. They represent the world as experienced and sometimes embellished by Curtis. For example, sometimes his stories varied depending on whom he was talking to. A similar problem occurred when evaluating the few newspaper and magazine articles in existence: they typically were based on what Curtis provided the writer.

Second- and third-hand descriptions (i.e., a friend told me that Curtis did such and such) are given little credence unless several individuals provided multiple examples of such events. In this jumbled universe of information, no doubt there may be inaccuracies in this article, but the overall presentation is believed accurate.

Curtis War Stories

Within the senior ranks of the NFA community, everyone has a Curtis Earl story; his reach was just that wide. To begin this article, it is instructive to tell three of my own “Curtis stories” to illustrate a representative cross section of the personality traits he exhibited throughout his career. At the time these events occurred, I was unaware of their telling implications and it was only after conversations with others that I recognized the underlying themes. In other words, while the stories are mine, the inferences are absolutely consistent with the broader context in how he interacted with others and ran his business.

In many respects, these traits were as famous as the weapons he sold, so it is appropriate to start with these first. Following these stories, we will return to the beginning and describe the events which may have influenced and shaped the man that so many thought they knew.

Curtis Stories

In 1996, I was in the market for a Reising and a friend told me that Curtis Earl probably had a wide selection in stock. Since I live near Phoenix, I gave him a call to set up an appointment to examine his inventory in person. I wanted to convey to him the message that this was a serious inquiry and already had done some research, including talking to some of the other dealers in the area. A few sentences into the conversation I mentioned a particular local Class 3 dealer, and this instantly resulted in a ten-minute tirade over why this dealer was a low life, incompetent cheat and SOB. I was totally flabbergasted by this uncalled for diatribe spewed at a potential customer. (Trait 1: He could unleash his wrath even upon total strangers if his mood or feelings about an issue prompted it.)

I later learned that the subject of his wrath was one of the early local dealers that, in Curtis’ mind, directly took business away from him. (Trait 2: He had an almost paranoid hatred of competition.) But Curtis was in a unique position, namely, an unsurpassed inventory, and I set up an appointment in spite of the baffling conversation. (Trait 3: He knew he could, and did, get away with a lot of bad behavior because of his unique collection.)

I asked a friend and local gun collector, Charles (Chuck) Olsen, to meet me at his house since he had known Curtis from a decade earlier and I assumed that this would help in the negotiations. That earlier relationship ended when Curtis told him, “Don’t bother calling me unless you are ready to do business.” Olsen took him at his word. (Trait 4: He could terminate a relationship in a second, and sometimes rather bluntly, if he perceived there was not something in it for him.)

I was twenty minutes late to the appointment, but was not overly concerned since it was at his house and knew that Olsen would be there ahead of me. After all, Chuck and I were ready to talk business. As it later turned out, this brief delay proved pivotal since it provided the opportunity for Curtis and him to reacquaint. Indeed, after this get-together they became close friends until the day he died. (Trait 5: On rare occasions, Curtis could become even contrite and apologetic and be willing to reestablish friendships.)

As I walked up to his door, Curtis came charging out, sans welcoming smile, stating that “I am going to have to charge you $50 for wasting my time, you’re late.” A rather odd way of starting a business relationship, I thought to myself. (Trait 6: Diplomatic business manners were infrequently exhibited; and Trait 7: He would often overstate the importance of his time and self-worth.)

He brought Chuck and me back to the vault and showed me the several dozen Reisings, mostly parkerized military versions, all at premium prices. I later learned that Curtis always charged top prices for his merchandise. The compensating factor, of course, was that a $1,000 Reising then is a $5,000 machine gun today. (Trait 8: He was absolutely correct in his predictions of the market and he used it to his business advantage.)

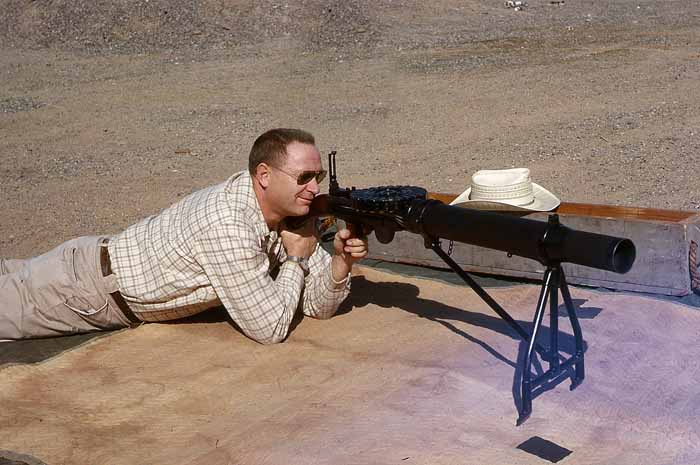

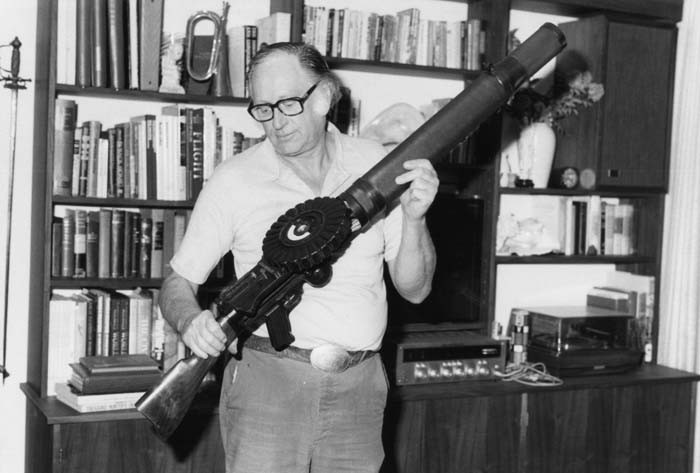

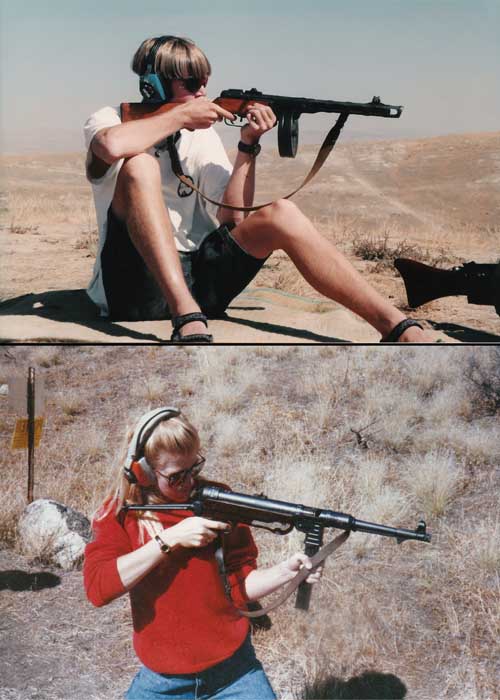

The second story occurred several years later when he was shipping the major portion of his weapon collection to the Idaho State Historical Society for the J Curtis Earl Memorial Exhibit. He had an inventory of ammunition for a 37mm Bofors and 25mm Puteaux and needed to dispose of it before shipping the cannons. He chose the best way possible: shoot it. A small group of friends were contacted to participate in the “disposal,” including Chuck Olsen who invited me along.

We arrived at his home at the appointed time and no one was around. Instead, we found what could best be described in legal jargon as the mother of all “attractive nuisances”: the two cannons on a flatbed and an unsecured truckload of ammunition and other weapons. (Trait 9: Towards the end, he had almost a cavalier attitude, not paying much attention to the potential implications and dangers of such behavior, not to mention the issue of monetary loss.)

We tracked him down at a restaurant and soon we were headed up the Black Canyon Freeway with a string of gawkers staring at the weaponry on the move. The group was comprised of experienced shooters, and there was no review of the range rules. Reactive targets were set up and the firing began. I had an M16 with optics and proceeded to pick them off on semi-auto. Curtis went ballistic and shouted, “No optics.” I removed the offending optics and started to pick them off with open sights. Curtis again went ballistic, “Full-auto only!”

I used aimed fire on the first round and proceeded again to take out targets, albeit with an accompanying burst of noise. Yet again, Curtis went ballistic. At that point, I had had enough and shouted back, “What do you want me to do? Point down range and just spray?” (Trait 10: He often had unwritten or unspoken rules, at least until you violated them and then all hell would break loose. It was thus difficult to keep in his good graces.)

When the cannons were unloaded and positioned, he gave the “honors” to one of his closest friends to fire the first round from these antiques not shot in decades. I got far away and shielded myself with Olsen’s van. What I found fascinating was that Curtis also removed himself from the proximity of the cannons and stood beside a truck. A dozen years later I had the opportunity to discuss this event with his friend that did the firing and he too had noted at the time that Curtis retreated to safety. (Trait 11: He always looked out for his own welfare. The welfare of others, including close friends, could be strangely problematic.)

The final story, and one that probably is the source of much of the consternation over Curtis’ business dealings, concerns a shoot that occurred after the sale of the machine guns from the J Curtis Earl Automatic Weapons Collection at the Champlin Fighter Museum in Mesa, Arizona. Several Class 3 dealers were present, including one that had recently acquired a Soviet PPS-43 submachine gun. Another dealer, also present, was one of the several dealers involved with these museum weapons after the collection was disbursed. It was the first time that very knowledgeable people had fired and thoroughly examined this weapon since it was sold to Champlin.

In Curtis’ catalogues he went into some depth to describe how you tell the good from the bad when it comes to remanufactured guns that are potentially “accidents waiting to happen” and the need to deal with “someone you can trust.” But upon close examination, the gun turned out to be a reweld, significantly lower in value than an uncut original. I watched the dealer’s jaw drop as he recognized that he would have to disclose this information in the next transfer and take a potential loss.

Some of this responsibility to “inspect first, buy second” fell on the shoulders of the interim dealers, but the point is that buyers found themselves in similar situations where the description given on a gun, sometimes bought sight unseen in other states, did not seem to match the item delivered. For example, on one occasion he held up a bottle of cold bluing to a friend and proudly declared, “This little bottle has made me tens of thousands of dollars.” (Trait 12: He claimed to always be fair in his business dealings, but this assertion would not always match reality.)

After reading these stories, seasoned NFA weapons collectors and dealers may be thinking, “Yup, these twelve traits pretty well summarize who Curtis was.” But he was far more complex than this. For example, Robert Segel, senior editor for this magazine experienced another dimension. As Robert explains, “I was interested in machine guns at a very early age. While attending a gun show with by father at the age of 9, I got my first machine gun – a Dewat Sten MkII for $25. I still own that gun. Of course I was too young to own a live one, but Dewats were within my realm. When I was about 13 or so, I ordered Curtis’ catalog and found an excitingly wide range of machine guns within my reach. I called and he was extremely helpful offering me whatever I wanted and if it was live, he would deactivate it for me. Even though I was a kid, still with a kid’s voice, I had done my homework, asked intelligent questions and apparently came across as a true potential, long term client. After a couple of phone calls, I raised the money to fly down to see his collection in person (wow!) and pick out an M1 Thompson in 1965. Over the next several years I bought 7 guns from him and he was always very patient with me and instructive about these guns, almost like a mentor to me. I have no ‘war stories’ about Curtis. All my dealings with him were straight forward, polite and honest.”

His granddaughter, Michelle Earl Cruson, experienced the humorous side of him. She shares some of her memories: “During one visit around Halloween, I displayed my pirate costume, complete with a plastic sword. I stashed it in the pillowcase I used to carry my goodies. As I was leaving, the bag poked me in the leg. Lo and behold, he had put a real antique sword in its place. He called it a ‘toad sticker’ and now my sword is displayed in Curt’s museum at the Idaho State Historical Society. Near the end of Curt’s life, when Hospice came, they asked him if he had any guns in the house. He cheerfully replied, ‘Yes, lots of them, everywhere!’”

So who was he – the mentor, the friend to some, the jokester, or the cantankerous, difficult business man? To gain some insight, it is necessary to start at the beginning and explore the major events that shaped the man.

Growing Up J Curtis

Curtis was born on July 15, 1924 in Tremonton, Utah to Jesse and Wanda Earl. His father, a farmer and WWI veteran, was born into a large family of farmers with four sisters and three brothers. His grandfather, Charles, was originally from Canada. By the 1930s, Curtis’ uncles, Leo, Frank and Ernest, were branching out into the grocery, sales and printing businesses, respectively.

What is intriguing is that even at the age of 5 he is listed along with his younger sister Marilyn as “J Curtis” on the 1930 census. But what did the “J” stand for? His daughter Pat explains, “He was named after his father, Jesse Wilson, but my grandparents did not want him called Jesse, Jr. so they named him ‘J Curtis’ from the very beginning and without the period. I suppose he would sometimes include the period because most people would expect it and think it was a typo if it was missing.”

He was a depression-era child which no doubt influenced his propensity for extreme frugality in later life, but unlike many of that period, his family was relatively well-to-do. At the age of seven, he became interested in collecting arrowheads on the family’s extensive property, which soon expanded to hunting and collecting other forms of weaponry, including cartridge collecting. The specifics vary as to how he got interested in guns. Max Rigby, his best friend from that period, said, “I believe his first gun was a .22. His Dad would take him out rabbit hunting with it. He also had a falcon when we were in high school that he trained to hunt. It was really interesting, I enjoyed going out with him.”

As far as his interest in machine guns, he told friends that he was given a crew served WWI weapon that was being thrown out by the local veterans group. In a 1981 newspaper article, he was quoted as saying that one of his father’s friends was going to throw out a pile of WWI souvenirs and rather than seeing them lost, “I laboriously hauled it home, using my bicycle as a cart and making several trips through the pre-pavement period mud lying between Tremonton and Garland some three miles away.” A 1983 prospectus for his business states, “His first two guns were acquired at the tender age of nine, he still has those two guns, both Maxim 08/15 machine guns.”

He attended grammar school in Fielding, Utah and at a young age suffered a major, life-changing event that would haunt him all his life. He would tell friends that when he was ten he was helping his father tar the roof and afterwards, while cleaning the tar off his hands and arms with gasoline, the volatile residual ignited when he got near the fire used to heat the tar.

What actually happened according to his daughter Pat was, “At the age of seven, while playing ‘Cowboys & Indians’ behind their Fielding farm home, Dad wanted their smoldering campfire to be bigger. He was drenched in gasoline while filling a small can from the old pump by the garage. As he poured the can of gas onto the embers, it flared and caught him on fire. Grandma Earl said she heard screams and saw him, totally engulfed, running around the back yard. She grabbed a blanket and ran to him. He was burned over most of his body, but it was the severe, third-degree burns over twenty percent of his body that took a very long time to heal. Most people in the area who knew of the event said that it was only by the power of Grandma’s prayers that he survived.”

Much later he told friends that the medical bills nearly bankrupted the family and his father resented him because of this. While plausible, this story is not true. Not only was the family quite wealthy, but Max Rigby recalls that he was treated at the LDS Hospital in Salt Lake City and the church picked up the balance of the bills, as was common in those days since the family was a “member in good standing.” Curtis seemed to have a knack for eliciting sympathy rather than rigidly adhering to the facts. In this case, it was the hard-working son versus the boy playing with gasoline.

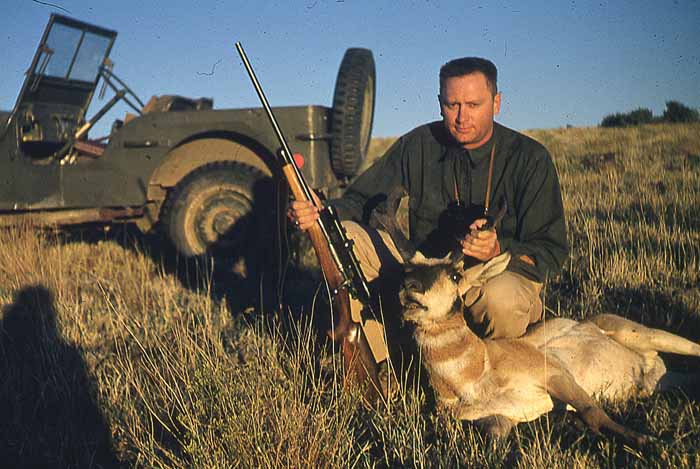

He was in enormous pain and the family was so distraught that they did everything to help Curtis. For example, he asked for a pet monkey and got it. He also took up an interest in plinking while convalescing after the accident. Plinking sparked more than just an interest in weaponry; it led to a lifelong interest in hunting and the great outdoors. In addition, he became interested in the Boy Scouts, worked his way up to Eagle Scout and treasured his badge all his life.

One thing he was definitely not interested in was farming, and friction began to develop between him and his father. His father was a hard-working stickler, and he expected no less from his son. He would later relate stories to close friends about how his father would even resort to corporal punishment if he did not meet his expectations. He told another friend, Mike Todd, that his father did not want him to have the machine guns that were being discarded by the WWI veterans and made him haul them back on his bicycle. He took them back, crying all the way, and hid them.

One thing that was certain, even among friends and relatives, he did not talk a lot about his relationship with his father. Dotti Cottle, his first wife, describes how he got along with his parents, “His mom doted on him. His relationship with his dad was work and money-oriented.”

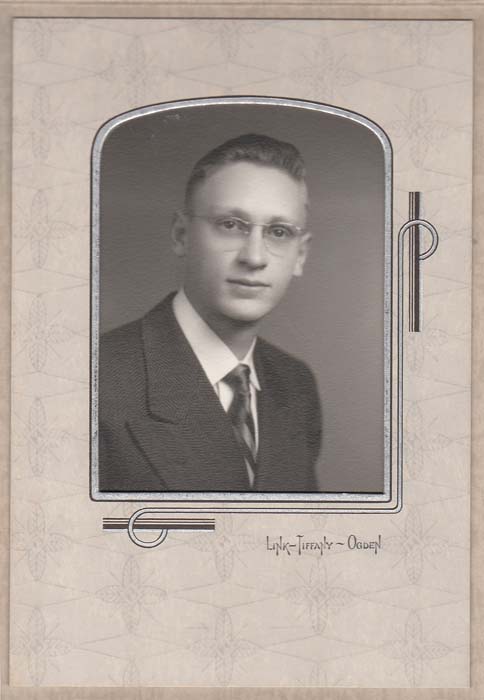

The Early Days

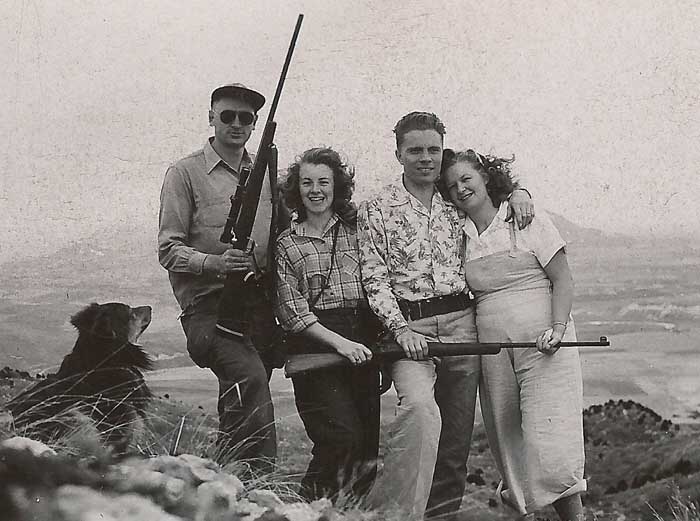

He attended Bear River High School in Tremonton and as Max Rigby explained, “He was a charmer. He had a knack for getting all the girls at the high school dances. We went on dates together and had lots of fun times.” This interest in beautiful women continued all his life, to both his detriment and benefit. After attending high school, he went on to The University of Utah for a year and later to Utah Agricultural College, now Utah State University, for five. In 1949, he graduated from the School of Forestry with a B.S. degree in Wildlife Biology with minors in Civil Engineering and Photography.

It was during the 1940s that he developed a love for flying and received his private pilot’s license in 1943. He told friends that he tried to enlist in the military during WWII, as his father had in WWI, but was rejected because of the damage done by the burns. One spot on his thigh never closed properly and was a constant source of concern for infection. As late as 1990, he was trying new procedures for skin grafts at the University of Utah Burn Unit to close the wound.

He was able to volunteer, however, to fly observation missions for the Civil Air Patrol near the end of the war. This proved to be the perfect combination since he could satisfy his love for flying and also have access to free rationed aviation fuel. All his life he sought such winning combinations. But nonetheless, to family and friends he repeatedly stated that it was hard to see all his friends serve, some coming home heroes, but not him.

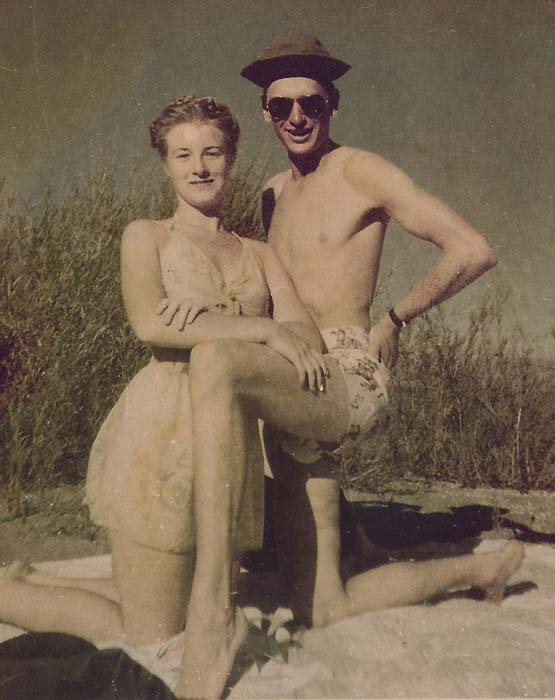

During college he married his first wife, Dotti, in 1946. “After his parents sold the farm in Fielding, his father bought into the Fish Haven Resort. Curt worked at the resort during the summers of his college years, renting the boats, working in the restaurant and maintaining the guest cabins. That’s where we got to know each other since my parents ran the main store and post office in Fish Haven, Idaho.”

In addition to the resort, Curtis’ father, Jesse, ran a business in Logan, Utah that sold some of the first automatic washing machines. Dotti worked with him instructing the ladies on the use of their new Bendix Washer. Jesse’s 100-year-old home in a prestigious part of Logan had the first automatic garage door opener in town, another business line that the industrious Jesse expanded into.

All the while, Curtis continued to expand and upgrade his weapon collection, particularly from veterans returning from the war. No doubt, the family indirectly helped in this regard from a financial standpoint. Dotti explains, “Grandpa Earl (Jesse) gave us a home on Center Street as a wedding gift. It was big and had four apartments in it, which brought us a little income. In 1948 our son, Michael Curtis, was born while Curt was out rabbit hunting.”

The family moved to Owensville, Missouri after he was hired by the Missouri Conservation Commission in 1949 to support the development of the August A. Busch Memorial Wildlife Area. He often told friends that this wildlife management area was his proudest accomplishment and must have influenced his later building of the Idaho Aviation Foundation.

Just after his first daughter Pat was born in 1951, the family moved to Phoenix where he secured a job as a wildlife biologist working on five federal projects as a project leader for the Arizona Game and Fish Commission. While he loved working on wildlife conservation projects, his deep-seated interest was in flying. Even his sister Marilyn caught the flying bug and worked as a United stewardess in the early 1950s. He similarly infected two of his children and two of his grandchildren (Michelle and Terrance).

His childhood friend Gail Halvorsen may have contributed to this love for flying for both him and his sister. Marilyn remembers fun times with Gail and the Halvorsen family. Gail became a command pilot during WWII in the United States Air Force. He became famous during the Berlin airlift as the original “Candy Bomber” who threw candy to the blockaded children as the C-47s and C-54s approached the airport. After the end of the blockade, Colonel Halvorsen did a “victory tour” around the state of Utah and Curtis flew in an accompanying plane taking photographs, some of which appeared in the book Halvorsen wrote about his life, The Berlin Candy Bomber.

It also may have been this love for flying that led to a major change in careers. In 1952, he went to work in the quality control and inspection planning department for Garrett AiResearch, a manufacturer of small gas turbine engines. The family lived on Diamond Street not far from Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport. Pat states, “In that house we had gun cases everywhere and we often drove to the airport to watch the airplanes take off and land. Dad loved animals; we had a dog (Butch), a cat and a pet desert tortoise so large that we tried to ride it. We were taught to respect weapons and thought everyone had guns and did such things.”

The Turbulent 50s and 60s

But those relatively carefree days would soon be over. The marriage began to unravel, but not before Dotti was once again pregnant. His frequent scuba and fishing trips to Mexico, the land of the lovely señoritas, no doubt contributed. A frequent traveling companion on these trips was a secretary at Garrett. He was not happy about his wife’s frequent trips taking the kids back home to Utah. It was an extremely stressful period and Christine arrived two months premature in 1955, the day after the divorce became final. Christine was so small at birth that the nickname “Tina” remains to this day.

Curtis claimed to friends that his father disowned him after the divorce. As stated earlier, his relationship with his father was tense at best much of the time. But in reality, his father helped him buy the Diamond Street house and set him up with the income from several businesses including a furniture manufacturing plant and several warehouses. Finally, when his father died in 1974 he received a sizable inheritance. There is a certain bitter irony in this, considering how he structured his own trust at the end of his life.

Dotti took the three children and moved back to Utah, living in the Earl’s big family home for the first few months while they wintered in a warmer climate. She found work as a secretary and returned her lifestyle to her calmer Mormon roots. Curtis remarried around 1959 to Beulah Holmes of Phoenix. Beulah had children of her own, slightly older than those of Curtis, and his own children got along well with her. But once again things started to unravel, this time on both the work and the marriage fronts.

Curtis was terminated from his job at Garrett in 1960, not for poor performance, but for what can best be described as a conflict with a certain female employee. Resolution of the matter involved company security coming to Curt’s house and leaving with hundreds of “artsy” photos of the young woman, although they didn’t get them all.

Curtis went through a string of jobs, most lasting brief periods, some part-time and overlapping. He went to work for Hollar Tool Engineering, Skyway Manufacturing, and DeVelco Manufacturing, all in quality control. He then changed careers again and went to work for Del Webb, an Arizona real estate, development and construction operation in Phoenix as a project estimator, then back to quality control for Apex Manufacturing while also working at Arizona Land Corporation. For a while he was selling real estate in Holbrook, Arizona. All this occurred from 1960 though 1968.

As for his marriage, this one was much more tumultuous than the first. So bitter and acrimonious had the relationship grown that Curtis was in fear of his life. Chuck Olsen explains, “Curtis told me that he knew his wife had a .380 automatic and knew how to shoot it. The marriage deteriorated to the point where he thought that she possibly might use it – on him – so he removed the firing pin. One morning not long afterwards when shaving, he heard a snap behind him and the clink of a round hitting the floor as another round was chambered.” This story has been confirmed by his granddaughter, Michelle Earl Cruson, and others.

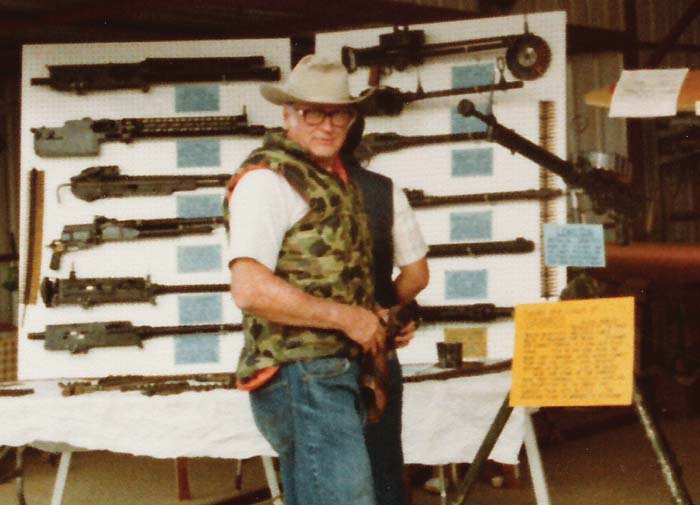

Needless to say, he was soon divorced. He remarried a third time to Mary Bess, but that only lasted a few years. His fourth and final marriage was to Lois Haselton in 1968, but it lasted literally a few days. The most consistent thread in this turbulent period was his uninterrupted dedication to gun collecting and flying. Sometimes he could creatively combine the two. At Arizona air shows, he set up a display of aircraft machine guns and explained the connection between guns and airplanes. From his (accurate) perspective, aviation advanced exponentially when airplanes became the delivery platform for weapons and the forward eyes of our troops. The guns, he would say, “were the fangs and claws of the war birds.” Kids of all ages were drawn to his booth.

He loved this attention and wanted to extend the concept to a permanent display. That may have been one of the reasons that years later he insisted that the Champlin Fighter Museum’s display of weapons bear his name, even though all the guns were owned by Doug Champlin. It also may have given him the inspiration for the J Curtis Earl Memorial Exhibit at the Old Idaho Penitentiary.

Another point of stability in this turbulent time was the frequent visits to his children in Logan, Utah. Friends got the impression that he was estranged from his children all their lives, when in reality he flew up several times each year and showered them with interesting gifts such as a live tarantula and baby alligator. His three children always looked forward to these visits.

The 1960s were turbulent times of job changes and dissolved marriages. His third marriage only lasted a few years. His fourth and final marriage lasted literally a few days. The most consistent thread in this tumultuous period was his uninterrupted dedication to gun collecting, flying and his visits to his children in Logan, Utah.

The end, in 1968, to the “marriage that did not count since it was so short,” as he would joke, also brought an end to the overlapping part-time jobs: in 1968 he was in the gun business full-time. The precise reasons that he became a full-time Class 3 dealer are not known. It was probably a blend of numerous factors. No doubt, being under the direction and control of corporations did not suit his style; déjà vu working for his father on the farm.

Another likely factor was the fact that from childhood he had developed the skills of an astute dealer and trader. He would shrewdly buy two guns, keep one and sell one then buy two more with the profits, repeating the process over and over for decades. A 1981 newspaper article stated that he “started out in the military arms business while still a kid. He supported his wildlife-management education at USU variously from farm work, gunsmithing, hawking war surplus sporting goods, and even aerial shooting (for bounty and furs) from an old Cessna 140 airplane.”

Yet another factor may have been a twist of fate. He told friends that a wealthy individual in the air cargo freight business was interested in collecting and investing in machine guns but could not legally own them. He helped Curtis apply for his Class 3 FFL in 1964. (Author’s note: 1965 is often cited as the start of his business; 1964 is the date given in the 1983 business prospectus and may represent the date he submitted the paperwork.) Curtis would later claim that there were only two other such dealers in the country, one in Wisconsin and one in Illinois.

The wealthy businessman would provide the money but Curtis would own and store the guns; the businessman could shoot them when he was with Curtis in Phoenix. Recognize that this was long before the straw buyer concept was even imagined, and, of course, Curtis kept possession of the guns. He was given the opportunity to fly around the country and began making key contacts in police departments that later proved invaluable. It was another one of those win-win situations that Curtis loved.

Curtis claimed that the businessman caught his wife cheating and this led to a tragic murder-suicide. All the guns, papered to Curtis, became his. This story is “real” as told firsthand to others, but again, the truth may lie elsewhere. He also told friends that he had received a large settlement from the judgment on a car accident, severe enough to require a fusion of vertebrae in his neck. Monthly income from the storage units given him by his father paid the day-to-day expenses. Additional money may also have come from the continued support from his father back in Utah. It is unlikely that he would ever admit this.

One thing was certain: he was reaching critical mass whereby the revenue from the part-time gun business was exceeding the income from his more traditional corporate jobs. In addition, he was living frugally and plowing the profits from gun sales into the purchase of more guns.

Regardless of what propelled him to graduate from collector to dealer, the net result was that on December 29, 1965, Curtis formally opened for business as a part-time Class 3 dealer until he went full-time in 1968. His first entry in his “bound book” was a Sten gun. (As an aside, throughout his life he used standard Ideal System Company eight-column ledger pages bound side-by-side and set up according to ATF record-keeping requirements.) The last entry was an MG-42 on July 14, 1999. The ledger tracked as follows:

- 1960s: 528

- 1970s: 1,556

- 1980s: 454

- 1990s: 27

- Total: 2,565

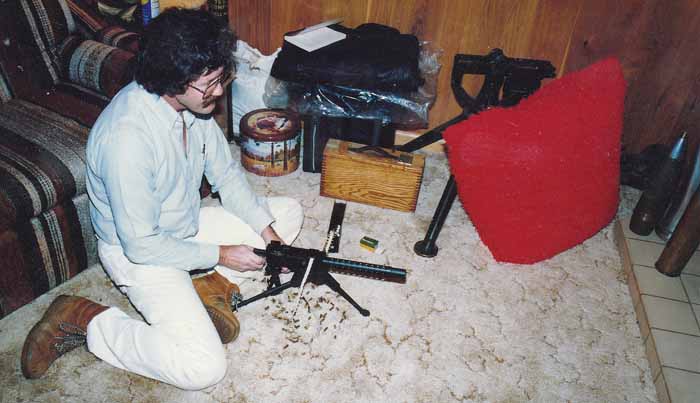

With a Title II inventory such as this and since he included his address in his ads, security was a constant issue. He built a separate structure on the property with overall dimensions of 12 by 27 feet, which included a vault with a time lock door imported from Spain and originally installed in the First National Bank in Florence, Arizona. Both his house and the external storage areas had what he described in the prospectus as “sophisticated security systems.” In reality, it was rudimentary according to close friends.

He always had a watchdog, usually a German shepherd, plus an assortment of hidden, loaded guns around the house and in his car. He built a special bracket to hold a 12-gauge shotgun under a coffee table, kept a .38 under a hat on top of the refrigerator and used as his primary defense weapon a WWII vintage .45 marked United States Property, SN 965435. He had it at the ready in a cut-off leather military shoulder holster stapled to the headboard of his bed. This gun would later be confiscated by the police in one of the darkest periods of his life just before he died. The Business Strategy

Clearly, the 1970s were the peak of his business, but it would be the very early days that proved critical since they laid the foundation of his business development strategy. As the 1983 business prospective detailed, “This business was built up over the years by primarily buying everything in the Title II gun line that he could afford. As the annual increase in the value of all of these items is far in excess of any other commodity, he continually poured his profits into more inventory and antique guns, he exercised the ‘new pots for old’ approach and acquired many collections and large lots from states, governments, and law enforcement agencies. He specializes in good, clean guns… he has become the largest dealer in the U.S. with an inventory most probably in excess of all of his competitors put together!”

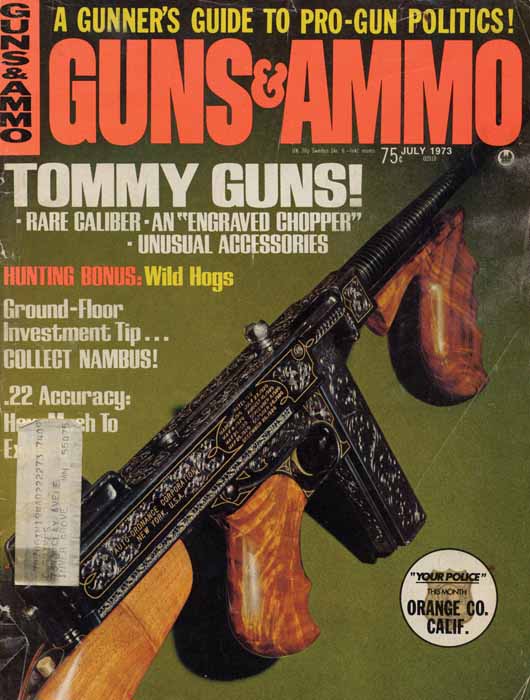

By the 1970s he not only was the largest Class 3 dealer, he was also one of the most influential. As mentioned in part one of this series, his father and three of his uncles were in the retail and sales business; maybe he picked up some of the skills from them and understood the power of advertising. He was one of the first to run national ads in widely read magazines such as Gun World, Guns and Guns & Ammo.

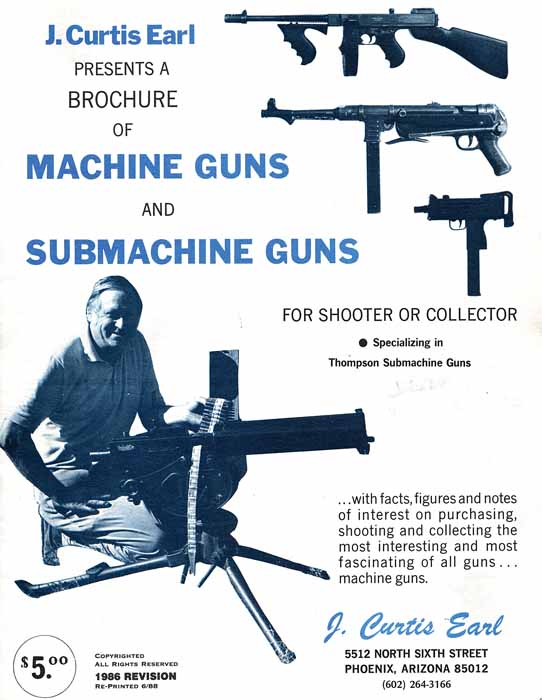

The ads may have been small, but they caught the eye of thousands who bought his catalog that was nothing short of breathtaking for NFA collectors with its dozens of illustrations. Between 1968 and 1983 he had distributed over 65,000 brochures. By 1983 he was receiving nearly $15,000 annually from catalog sales alone (nearly $34,000 in 2009 dollars). Curtis also was quick to adapt new photo technology, owning several Polaroid cameras and getting into home video back when cameras required a suitcase-size recorder. For those interested in getting a closer look at a particular gun, he offered to take and send a custom photo, “$1 submachine gun photo, $2 light, and $3 crew served or heavy guns.” He even made and sold tapes of guns to potential buyers with a narration of the gun’s statistics and qualities.

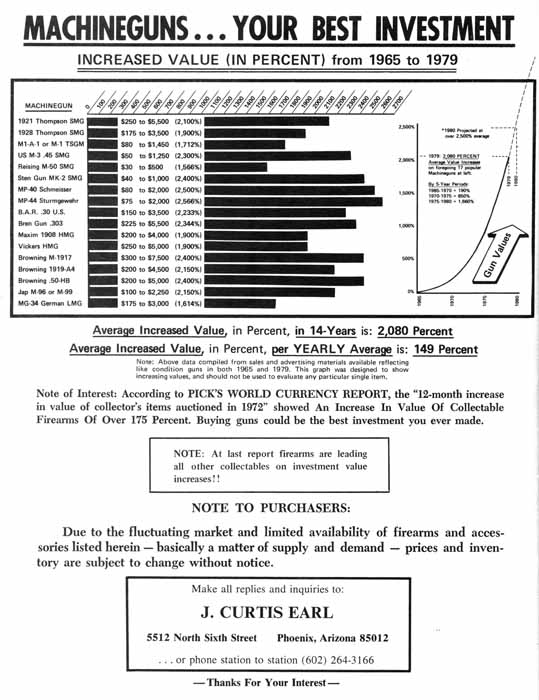

Curtis did three things in his catalog that greatly benefitted the collecting public. First, he educated them that they could own machine guns and explained the process to legally acquire them. For example, wording from the 1976 catalog states, “Machine guns are legal. They always have been! However, old wives’ tales to the contrary are bolstered by our American new media (sic), the reverse of this has been very effectively drilled into the public’s brains.”

Second, he pointed out the rarity of the classic original guns and the impact on supply and demand: “It is now simply a matter of supply and demand… with the demand far greater than the supply!” and its impact on price: “Any machine gun worth having will demand premiums unheard of today; they will fall in the same category as the Colt Patersons or Walkers, or any of the other highly sought and very costly collectables.” He was correct, of course, but in those early days he never anticipated the astronomical rise after the 1986 ban on the manufacture of transferable machine guns.

Part of his logic on the inevitability of price escalation was based on the impact of the transfer tax. “On each transaction of a live gun, the value of that gun is increased by $200.00.” As he detailed, the owner of the gun in each succeeding transfer would want to recoup his original cost, plus expenses, plus a profit. As he explained, after several transactions, “The $59.50 Thompson (Author’s note: Interarmco was selling these at this price in 1967) is now listing at $500.00. The new buyer pays the $200.00 federal tax, making his total cost for the gun $700.00… and ad infinitum.”

Third, he provided a summary of the classes of machine guns, key dos and don’ts, the possible problems with remanufactured guns or “re-wats,” the regulations and the legal traps, sometimes in brutally frank terms. For example in his 1988 catalog, after the dust had settled on the historic ATF raid, “(Un-registered) guns brought home by an earlier collector as a war memento, or something from prohibition days… will show up… now and then… but contraband they are, and contraband they will most likely always be… good for spare parts only. The BATF Gestapo loves to find the ‘innocent’ owner of such items… You may as well get caught with a kilo of ‘H’.”

Curtis had eight business advantages that, in sum, no one else had. First, he had a lifetime of collecting, bargaining knowledge and contacts. He knew guns and where you could get them. Second, he had a tremendous inventory from day one of the business. Third, the market timing was in his favor. He went into business during the golden period, long before the astronomical rise in machine gun prices and the field was packed with competition. Fourth, he had the capital to buy large lots of weapons from collectors, police departments, movie studios and prisons. Fifth, he had a knack for self-promotion and advertising. Sixth, he had something that few had – an airplane and a pilot’s license which allowed him to traverse the country looking for deals. Seventh, he could work out of his home, thus eliminating the cost for a storefront. Zoning was not an issue. Eighth, he had fortuitous luck as explained next.

The Thoresen Gun Runs

Mentioned earlier was his chance encounter with a wealthy air cargo freight business owner that may have helped jump start his dealer career. Again, this may or may not have occurred, at least to the extent Curtis would tell the story to several friends. But there was no question about another chance occurrence, one that eventually was described in the 1974 book, It Gave Everybody Something To Do, by Louise Thoresen.

Born Louise Banich into a blue-collar family of meager means, at the age of twenty-one she met and married William Thoresen, a Chicago trust fund millionaire. He may have had wealth, but he was also an unstable manipulator and petty criminal who had visions of grandeur, including dreams of establishing a military arms museum in San Francisco.

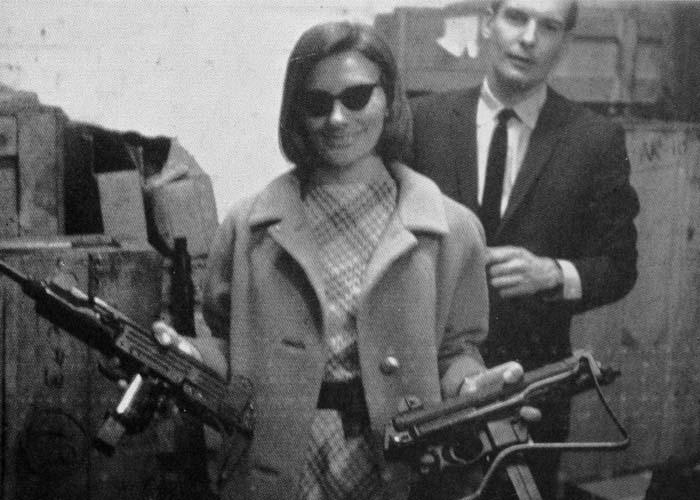

Louise wrote, “So once again I was caught up in his schemes and agreed to embark with him on this new adventure – into the upper echelons and lower depths of the gun dealing world.” Curtis’ ads had caught his eye and he made arrangements to meet him at his home in “Santa Fe, New Mexico.” In the book the characters’ actual identities and locations were not revealed. Curtis was “Orval Lee.”

Jumping directly to the end from Curtis’ standpoint, this wealthy individual paid for Curtis to fly around the country, build key contacts and support William Thoresen’s efforts in assembling an arsenal reported by federal agents to weigh as much as 70 tons. Fast-forwarding to the end of this story from Louise’s standpoint, the marriage disintegrated, he abused her and in a famous California trial, she was acquitted of the murder of William by reason of self-defense.

A careful read of the book reveals more than just Curtis’ fortuitous encounter with Thoresen to expand his network on someone else’s dime – another one of the win-win deals he loved. It also revealed the near paranoia and suspicions that influenced a few of the buyers and sellers from that period. On page 192 Louise wrote, “Within two hours, two FBI agents came to our motel and arrested William on the fugitive warrant from Tucson.” (Author’s note: ATTU was the Alcohol, Tobacco Tax Unit of IRS, as it was called back then before independence from the IRS in 1970 or so) “We later learned that Orval Lee had begun making immediate inquiries about William and the ATTU and the FBI… He knew from the FBI that William had been arrested, but he was still chary that it was all part of an entrapment plot to nail him.” (“Him” is emphasized in the original.)

On page 202 Louise continues, “‘I do not want to go there,’ Orval said. ‘You take care of it. You take me to Newark Airport now’… No amount of persuasion would change his mind. We did not understand what all the panic was about, but we drove him to Newark Airport anyway… It should have occurred to us that Orval Lee’s sudden departure from the gun run was much more than an omen, but neither of us was very good at looking into the future.”

Hours later Louise Thoresen was arrested for “storing explosives at an airport and attempted interstate shipment of explosives and contraband firearms.” Years later Curtis would tell friends that he thought the Thoresens were trying to set him up in an ATF sting operation.

Double Dealing and Contraband

On page 194 Louise implies that Curtis was ready to facilitate contraband deals, “Look, let me tell you something, Lee said expansively. ‘The ATTU told me not to do business with you at all. But I think you’re a nice guy… your wife is nice… He looked at me with much more than casual interest. ‘I’ll work with you on it… I’ll take a deposit on the papered weapons you want, crate them and store them in a bonded warehouse till we can transfer them to your name. And in the meantime,’ he grinned expectantly, ‘maybe I know about a few things you can buy right now from friends of mine. Unpapered. Machine guns you wanted, wasn’t it?’”

Thoresen’s comment about the lustful look-over was absolute pure Curtis. No doubt that happened. But I have been unable to uncover so much as a shred of information that he ever knowingly dealt in contraband. From the 1930s to the 1960s, the world of machine guns was different than it is today and as documented in earlier interviews in Small Arms Review of leading historic figures in the industry. The draconian controls today did not exist in days past.

Maybe there were some less than perfect deals, but it is highly unlikely that Curtis, a financially well-off dealer, would have put his collection, which was his pride and joy, and his growing business, which was a major source of income, in jeopardy, all to earn a few extra bucks. He was definitely always looking to abscond with a few extra dollars or score some trinket he had his eye on, but felonious activities were unlikely.

He did run into an issue in 1976 that eventually resulted in the confiscation of 13 machine guns and one silencer. In his bound book he listed their removal as “ATF Commandeered.” He bought from the Kearny, Arizona police department one Ruger AC-556 machine gun, three M60 machine guns and one M-11 submachine gun. The ATF alleged that the transfer was arranged to take advantage of the police and military discount on the price of these new guns – in effect, a straw purchase through Donald Lane, the Police Chief. In addition, some manufacturers would only sell directly to the military and law enforcement. ATF allegedly used this as justification for the subsequent search warrant and raid in June 1977. Curtis claimed that all these transfers were done with full approval of the ATF.

Curtis was extremely cautious, to the point of paranoia. For example, he frequently would tape record telephone conversations and some of these tapes still exist. Even the ATF was aware that he would record conversations. These recordings stand as vivid testimony to Curtis’ skill as a crafty tactician and brutal negotiator. Several involved talks with Louise Thoresen after she was acquitted of murder and re-acquired all the properly papered guns that were part of the estate. She told Curtis that she was offered $5,000 by the ATF to set up dealers.

In her book, Thoresen also raised the possibility of Curtis being an agent for the government, essentially a snitch. On this, the record is clear. He was. Curtis helped from time to time when he wanted to court favors or defensively position himself.

His July 1979 Senate testimony was explicit, even mentioning some of the Thoresen dealings and tape recordings:

Senator DeConcini: In what manner did you cooperate with the agencies?

Mr. Earl: Primarily acting as an informant to the FBI and ATF people in turning in people who I know were bad guys.

Senator DeConcini: You had acted as an informant for ATF?

Mr. Earl: Many, many, many times.

Senator DeConcini: At their request?

Mr. Earl: No sir; because I felt it was the duty as a citizen to do so.

His daughter Pat was aware of her father’s cooperation with ATF, “In 1983 I was working for TransWest Air Service in Salt Lake City at the front counter renting airplanes. Two ATF agents flew in and waited at one of the nearby tables until they got their orders to pursue a suspect. They flew off and returned in less than an hour. In the meantime, the office had called and asked for them and inadvertently mentioned that they were from ATF. I assumed that they lost their suspect and mentioned something to effect, ‘Looks like somebody got away from the ATF.’

“One of the agents was surprised and asked, ‘How do you even know what ATF is?’ In typical Earl fashion, I told him bluntly, ‘You guys have been pretty nasty to my father, J Curtis Earl.’ One agent immediately said, ‘One of my first ATF assignments was to check his books for several illegal weapons we were trying to locate. I spent all day and found nothing. When I was leaving, your father asked what prompted the inspection and I told him exactly what we were looking for. He responded, ‘I do not deal in illegal guns. You should have asked me in the first place.’ Then he proceeded to tell me exactly the information I needed and the whereabouts of the guns. I have a lot of respect for that man.’”

Getting back to the original point, namely, Thoresen’s version of what went on. Just how truthful was she in all this? Autobiographies are inevitably spun to favor the author. She killed her husband and she was, to some extent, rationalizing her actions. In the book she made numerous references to deals in transferable, properly papered guns across the country in which Curtis allegedly was involved. Cross-referencing his bound book from that period reveals no connection to these possible deals. The book may be accurate in broad terms, but in terms of any specific illegal operations which may have involved Curtis, the evidence is weak.

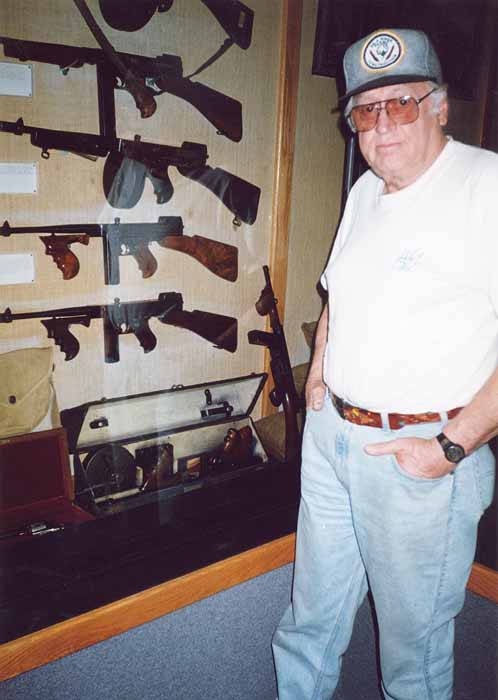

A Collection of Dreams

By 1983 Curtis had amassed an inventory of approximately 800 NFA firearms. There were complete “sub-collections” of machine guns which he divided into the categories of (1) assault rifles; (2) light and heavy machine guns; (3) submachine guns; and (4) silencers and silent weapons. These were further broken down by country of origin. He had complete or nearly complete collections of English, Japanese, French, German and American guns plus others, from the first machine gun invented up to, at the time, the latest U.S. M60. He also had a nearly complete collection of aircraft machine guns. There were military, commercial and even prototypes. He also became the primary distributor of the E. H. de la Garrigue half-scale miniature Thompsons.

The center of the collection and what he was most noted for, aside from some specific guns mentioned later, was what he claimed to be the only complete Thompson submachine gun collection in the world. So extensive was his collection that Gordon Herigstad, author of Colt Thompson Serial Numbers, sought out and was given access to his bound book records in 1995. Later, after Curtis died, he produced a separate listing for all Thompsons Curtis had from 1965 through 2000. On Curtis’ bound book at one time or another were the following:

- 199 Colt Model 1921, 1927 and 1928 Navy

- 109 Savage Model 1928-A1 and 1940-41 Auto-Ordnance

- 81 Savage Model M1 & M1A1 and 1942 Auto-Ordnance

- 67 1952 Numrich Arms Corporation Thompson Model 1921 & 28

- 35 West Hurley Model 1928 & 27-A1 Semi-Auto

He had five consecutively serial numbered sets (i.e., 10 Thompsons total). Some were movie guns from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Studios or television guns such as those used in the TV series, The Untouchables. Many were from police departments around the country or from notorious prisons such as Attica, Sing Sing, Folsom and San Quentin. One incredibly engraved and ornate 1921 Thompson was dubbed the “Midas Touch” and it made the cover of the July 1973 issue of Guns & Ammo. This was another form of advertising that attracted new, high-end customers.

His inventory also included approximately 200 Title 1 firearms, some standard, but mostly rare collectable rifles, pistols and shotguns, especially Lugers, Mausers and Winchesters. There were also seven cannons ranging from 20 to 75mm. He had tons of ammunition and accessories; some rare accessories were more valuable than the guns that they were designed for. A lot of the inventory was impressive just because of the sheer volume of particular models. Aside from the Thompsons, he had 66 MAC M-10s and M-11s and 44 Reisings. He also had a mind-boggling collection of German MG 34s and 42s – 33 in all.

The 1983 business prospective totaled the value as follows:

Firearms (Title I and II)

- $1,450,000

- Destructive Devices

60,000 - Accessories and spare parts

150,000 - Ammunition

15,000 - Total

(1983 dollars)

$1,675,000 - Total

(2009 inflation adjusted dollars)

$3,600,000

Of course, gun values did not track inflation, a fact pointed out by Curtis himself. If one were to make a guess of the average value of the guns at $10,000 each, one can see that this inventory, if it existed today, could approach $10 million. This is all just idle speculation since some of these guns would sell today for somewhere between a few hundred dollars to a hundred thousand dollars or more each. Examples of a few of the more exotic guns in this later category included the following:

- Charles Nungesser, WWI French flying ace’s Lewis aircraft machine gun responsible for 38 German kills

- Pancho Villa’s Lewis machine guns confiscated by Arizona authorities in their original shipping containers

- Thompson experimental 9mm model serial number S1

- Thompson Model M1A1 presentation commemorative made for President Eisenhower

- FN-FAL select fire Serial number 1

- Gewehr 43, semiautomatic Mauser code ac44, presented by the Walther people to Alfred Jodl, WWII German military commander

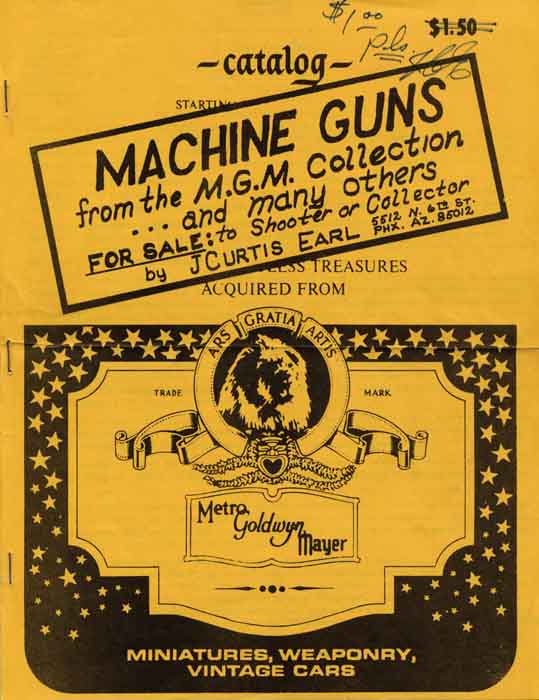

The MGM Automatic Arms Collection that he acquired at public auction in 1970 was so extensive that he prepared a special catalog detailing the items. They represented all of the machine guns used by MGM in their movie and television productions over a 40-year period. This included World War I and II movies, Pancho Villa and the Spanish American War movies and “general shootouts of all descriptions, including the Tarzan flicks where three of the Vickers were used.”

Television series included Combat and Rat Patrol. These were guns used by Wallace Berry, Clark Gable, Humphrey Bogart, Edward G. Robinson, John Wayne, James Cagney and others. Twenty guns were transferable and those that were not, such as several of the .50 caliber Brownings, were parted out and the receivers destroyed by the ATF. This MGM lot also included spare parts and accessories, some in mint condition.

According to a letter dated January 8, 1992, 188 guns in his collection were sold to Windward Aviation, Inc. (Champlin Fighter Museum). Indeed, there were so many transferred in that one sale that he prepared a special rubber stamp to make each entry in the ledger. Even after this single lot sale in 1987 and other individual sales, he still had approximately 520 Title II weapons in 1992 because of new additions. These figures did not include his personal guns and all of the specialty items such as ancient weapons and armaments. Many of these went to the J Curtis Earl Memorial Exhibit in Boise, Idaho.

Business with the Rich and Famous

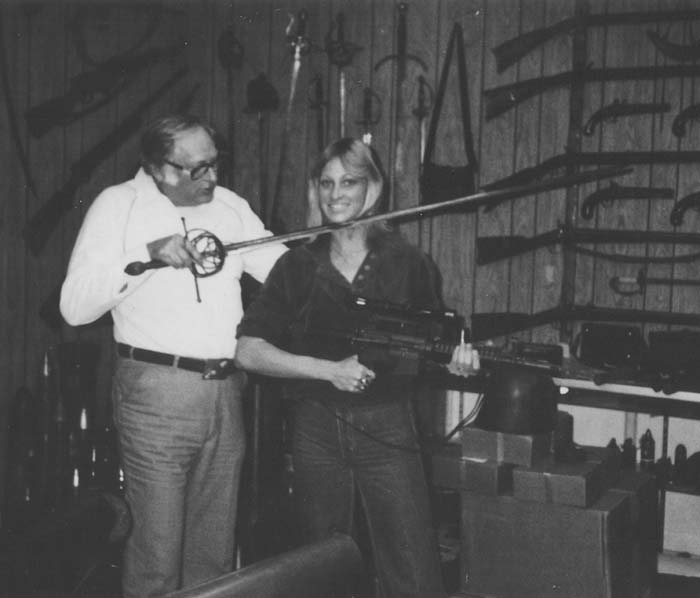

Needless to say, Curtis and his collection were attracting international attention, including interest from very wealthy and connected individuals. From time to time Curtis would relate stories to friends who took these in, but sometimes wondered if he exaggerated. After his death, however, a number of photographs and other records verified these stories.

Some of these prominent connections were not related exclusively to guns. For example, he claimed that he would scuba dive with Jacques Cousteau in Mexico. He also was a friend of Frank Tallman, a stunt pilot, who worked in Hollywood in the 1960s and 1970s. Tallman was the president of Tallmantz Aviation which supplied a fleet of operating B-25 Mitchell bombers to recreate a Mediterranean wartime base as depicted in the 1970 movie Catch-22. The flying was done in Guaymas, Sonora, Mexico and Curtis dressed in a uniform and sat in the co-pilot’s seat. The production required three months to shoot and the bombers flew a total of about 1,500 hours. Curtis was in heaven: he could not be in WWII for real like his friend, Halvorsen, but he got to play a bomber hero in the movies.

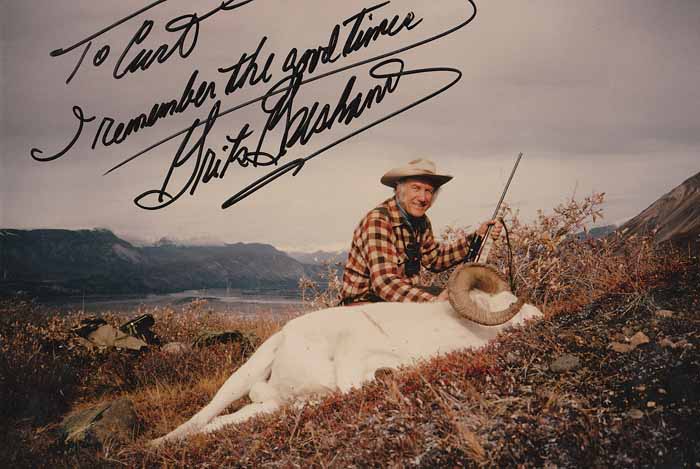

He had pictures of himself with actors such as Mr. T (born Laurence Tureaud) who starred in the television series The A-Team and autographed photos from celebrities such as Grits Gresham, host of ABC’s The American Sportsman series from 1966-1979. There were copies of records of export licenses for guns sold to Middle Eastern sheiks. Curtis would marvel to others at how these otherwise complicated export deals would proceed through the bureaucracy at lightning speed for the diplomats. One friend relates the story of arriving at his house to find a shiny new Ferrari in the driveway, “Curtis and the owner had been fighting over the price of a case of ammo – like their very existence depended on the last few dollars of price difference. The case of ammo wouldn’t fit in the trunk, so it rode in the passenger seat.”

He entertained his friends with these stories, but the events were also a harbinger of something else… a growing interest by federal agencies.

The Feds Arrive in Force

During the 1970s there was a series of compliance inspections by the ATF at Curtis’ residence in central Phoenix where he also conducted business and stored his collection. For the most part these were routine, but by the mid 1970s the tenor with the government agencies began to change, even though he had been cooperative with the ATF. In a number of instances his actions were, in fact, to inform on their own agents who were conducting sting operations of questionable legality.

He was “influencing people” but not “winning friends” within government bureaucracies and, eventually, this and other factors such as the Kearny, Arizona, gun deal led to the infamous 1977 raid. The details of that raid plus an entrapment scheme using a woman he briefly dated were covered in Volume 4, Number 4, January 2001 issue of Small Arms Review. There are, however, several additional points of note.

Curtis was extremely cautious, having almost a second sense when trouble was brewing. For example, Curtis told friends years later that he sensed something was odd the day before the 1977 raid. A telephone lineman showed up and spent a lot of time working on the telephone pole behind his house. The ATF was setting up a direct communication line to Washington.

In the Senate testimony he stated that as the raid unfolded, “A guy went running across the lawn, stretching the longest telephone extension you ever saw – something like a 250 yard telephone line.” The ATF knew he potentially had recording devices on his business line and they apparently wanted to immediately plug into a dedicated, secure line. This was in the days before cell phones.

In December 1978 the government presented evidence to a grand jury on the Kearny, Arizona, gun deal – the issue that triggered the 1977 raid. The grand jury returned a “no bill” against Curtis, but indicted Donald Lane, chief of the Kearny, Arizona, police department on two counts. However, in early February 1979, the chief was acquitted on both charges. In November of that year Curtis initiated a lawsuit against several agencies for $8.4 million for “malicious prosecution.” He would later claim to friends that he had to drop the lawsuit because, “If I don’t, the Feds will not renew my dealer’s license.”

The legal difficulties were costing tens of thousands of dollars and were wreaking havoc on his business. In July 1979 in Senate testimony he stated, “For the last two years I have been working under a suspended license. I no longer have a legitimate license to send to my dealers and customers. I have a two-bit letter that tells me I can work as an authorization on this letter in lieu of my license, which, in effect, tells everybody I do business with I am in a bad light with ATF, and most people don’t know what a letter is. They are not used to seeing it. They don’t know if I am in business or not, and it is greatly damaging my business reputation – what is left.”

The description of the raid and Curtis’ testimony is mandatory reading for all NFA collectors (transcript available online, Google: Curtis Earl CIS 1980 S181-2). Indeed, a 2003 Neal Knox report in Shotgun News, highlighted Curtis’ testimony and the fact that it was one of the first real exposures of the problems with the NFA record-keeping problems that remain unresolved to today.

The Tensions Build

Curtis may have prevailed in this costly David vs. Goliath battle in the 1970s, but the stress was having an impact on his health and his interactions with others. Some of these stressful situations were through no fault of his own.

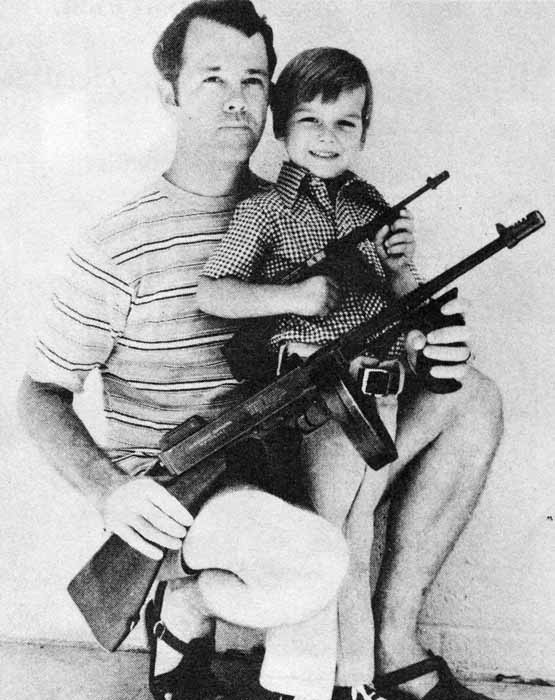

For example, Curtis stated in the 1979 Senate hearings, “A friend, FBI agent Kelley Sanderson, was ordered officially to not contact me, not have anything to do with me, and this was a direct result of an ATF visit to him. It is a sore deal… I took a picture of Kelley and his little boy, father and son, the kid holding the miniature (Thompson) and Kelley holding the big one. They demanded a statement why would he allow himself to be photographed, used in my book and advertising my brochure, which I have been putting out since 1966… Today, he calls me maybe once every six months to see if I am alive. He is scared to death he will be transferred to Timbuktu.”

In addition, a life-changing tragic event intervened once again. His daughter Pat relates, “Dad was thrown into a tailspin when Mike, his son, died in an airplane accident at the age of 23, the day after he graduated from USU. Between December 1966 and March 1972, Mike logged 1,741 hours of flying; that’s a lot. Having been in the ROTC at USU, he was scheduled to go into the Air Force upon graduation. He was Dad’s pride and joy, his life, his legacy.”

Curtis continued to make trips to Utah to not just see his two remaining children, but also the growing number of grandchildren. In some respects, he was like the proverbial Dutch uncle who could shower interesting gifts, play with the grandkids and then, literally, fly away. Pat recalls, “The grandkids enjoyed visits with him. Not every kid on the block could say they got to shoot a Thompson machine gun with their grandpa, or learn about falcons, or how to swing a two-handed sword. Adventures with Grandpa Curt were rich.”

But life with relatives did not come without a price, at least for them: gifts and love always seemed to come with his unwritten and, at least initially, unspoken rules and conditions. It was quite simple, there was the “wrong way” and then there was “his way.” And it was always his way or the highway.

Blood relatives always cut a lot of slack for kindred. But with customers and especially dealers in the NFA business, these affronts did not go down well at all. Even U.S. senators did not escape his sting, as illustrated in the 1979 testimony transcript, “Before I start, I would like to give you (Senator DeConcini) a belated thanks for sending your assistant to my license revocation hearing, and for the five seconds he spent there during our six-and-a-half-hour session.”

He was relentless right up until the time of his death. What’s more, he knew it. In his 1973 résumé he stated that he was “a bit opinionated in what I believe.” In addition to being a rather odd comment in a résumé, it was the understatement of the century. He proudly posted a framed inscription on the wall of his home that stated, “No man should go through life without a little trouble.”

While his interactions with others were the stuff of legends, they were rarely put in writing. One of these documented examples was in correspondence between Curtis and a rich, Scottsdale-based business executive who had bought nearly $150,000 in weapons from Curtis over a relatively short period. The businessman wrote, “I have become frustrated and have decided to terminate the relationship.” Curtis shot back with the opener, “To the smart X-suit peddler from the dumb X-farmer.”

Roger Cox, author of the 1982 book, The Thompson Submachine Gun, wrote on page 12, “This dealer… had a machine shop produce some thin, boxy looking imitations (of compensators). When this dealer published his catalog, he referred to these poor copies as ‘First Model’ compensators… Since this unscrupulous dealer was the first person to give any kind of designation to different types of compensators, his scheme was adopted by nearly everyone. It is foolish to perpetuate this fraud.” This allegedly was Curtis.

The Cycle of Friendship and Animosity

Most personal and business relationships would start amicable enough only to end in bitter hostility. This was a pattern that was repeated all his life. As stated at the beginning of this three-part series, everyone has a Curtis story and we have already provided a sampling. Some of the most outlandish, although verified by reliable and independent sources, cannot be put into print. There are several areas, however, that we will explore further because they are representative of why he was so legendary.

We recognize that if he were alive to defend himself, he would have a different take on all of this. But there are some stories that are just irrefutable and supported by multiple, credible sources. Indeed, in preparing this article we would hear both sides: as he told it to friends and again, as told from the other party.

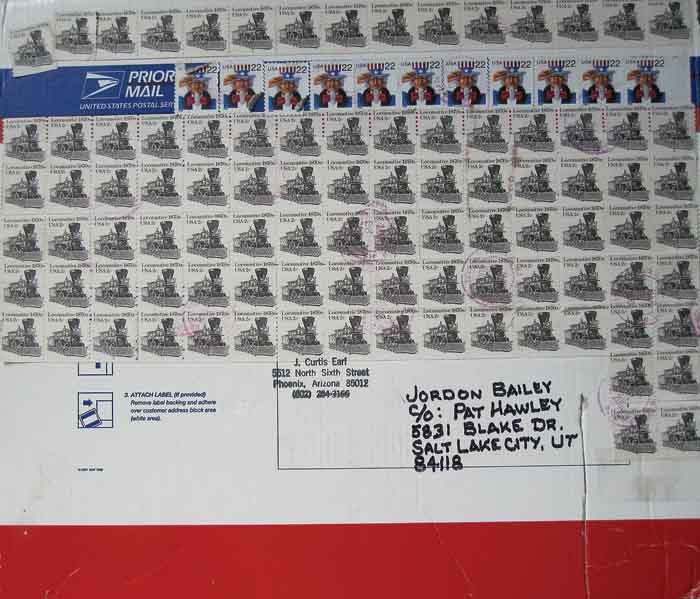

He was frugal to a fault. Sometimes his frugality was comical, as when he took the time to paste scores of two-cent postage stamps on a package. Sometimes it was baffling. For example, many readers would expect that a famous multi-millionaire gun collector would have as his personal defense gun a custom weapon by the likes of Armand Swenson or Frank Pachmayr. Instead, he asked his friend of nearly 40 years, Mike Todd, to build his from mismatched WWII surplus parts, specifically, a Remington Rand frame, an Ithaca slide and a mixture of internals.

Curtis absolutely thrilled in absconding with some trivial item from someone else. Mike Todd states, “I suppose that some may call it kleptomania, but on a number of occasions I was shocked to witness him take some trivial item and put it in his pocket. It was as if he was not even aware of what he was doing.” One individual interviewed for this article reported that he returned some ill-begotten items to their rightful owner after Curtis died. Other highly credible sources have told similar accounts such as the widely circulated story that security procedures were changed at the UK’s Ministry of Defence Pattern Room soon after a visit from Curtis.

Sometimes the excitement of a potentially questionable deal got the better of him. For example, the thought of owning historical military aircraft intrigued him and in 1982 he traded a Cessna 180 for a WWII AT-6 trainer. By 1989 he had sufficient money to not just buy prop-driven airplanes, but jet fighter aircraft. He bought a Chinese MiG-15, but the wings were improperly removed, destroying critical cables. He decided to manage the process himself and went to Beijing. Pat recalls, “He also bought dozens of new Chinese flying jackets – something really rare in the U.S. – and stuffed them in the fuselage. Well, it backfired. Customs found the jackets; he had to pay a fine and he gave most of them away.”

These stories are fascinating and amusing, but they do not get to the area that was the source of so much consternation. Curtis had to win every negotiation no matter how petty and dictate the terms of every transaction. Even if he gave something away, he still felt it was his to control or even take back. He may have been a multi-millionaire, but he obsessed in his ability to obtain things that others wanted and thereby control or influence others. Indeed, he reveled in it. Some specific examples help illustrate this trait.

Steve Earl, his grandson, states, “In 1997 my wife, Monica, and I visited Curt at his house in Boise. We had a great time and later that year I called and asked about my dad’s (Mike Earl) Maxim machine gun that he told me I could have. I also told him I would like to get a Tommy Gun from him, as this would be a great memento of my Grandpa. He told me he needed to drive his motor home to Boise and that if I did this road trip with him, he would give me the two guns. I flew to Phoenix, he did the paperwork for the two guns and I drove back as far as Logan with him.

“Curt called me that fall and asked if I could build him a used computer for a friend. I said I would be glad to and asked if he would like us to come up for Thanksgiving. He was alone and said he would really like that. We went to Boise, set up his friend’s computer and did a lot of yard work. He asked if I had sent in the paperwork for the guns yet, and I told him that my apartment was packed from top to bottom and that I would send the paperwork in just as soon as I had a place to put the guns in a safe place.

“I got a certified letter in the mail a month later and was told to tear up the paperwork for the guns as they had been sold to someone else. I called Curt and asked what was going on. He said this was because I didn’t send him a Christmas card. I explained that I had been overwhelmed with school, work and selling computers and that I hadn’t sent anyone a Christmas card that year. Well, having inherited Curt’s temperament to an extent, I told him exactly what I thought about this and then some.”

A similar story is told by Mike Todd. “Curt promised me a rare .50 Browning. I was busy and did not immediately submit the paperwork and at Christmas, the year before he died, after giving him my gift, he informed me that he had sold the gun and donated the money to the NRA. He told me, ‘It could not have meant much to you if it was taking you so long to get the paperwork in.’”

Yet another story is told by his daughter Tina. “In 1981 my husband and I helped him paint the Phoenix house and trim up the palm trees. After doing this, he surprised us and gave us a boat that had sat in his yard, unprotected, for about 10 years. We thought it could be a good long-term project and something to enjoy for years to come.

“All told, we spent nearly $1,000 over the winter buying new tires for the trailer, cables, electrical stuff and wood that we used to fix the top of the boat over the winter months in our spare time. All winter Dad kept on us to get it done so we could get it in the water. He said a friend was interested in restoring it if we didn’t want to do it. One day the next summer Dad showed up, hooked it up and took it away. He never gave us a dime in compensation.” Curtis would later tell his friend Mike Todd that he had paid for all the repairs and his daughter was letting the boat get destroyed through neglect.

Reaching the Limits

The point of the preceding stories is that if Curtis did this to family and friends, one can only imagine what happened to strangers or business associates. For many, such as this author, they do not have to imagine; they have heard dozens of such stories in the NFA community. But recognize that there is a distinct difference between the anger experienced over a bad business deal and the pain felt when Curtis interacted sometimes with friends, relatives and even lovers.

The problems he wrought finally reached a threshold limit for some Class 3 dealers and organizers of local shoots. One stated, “For years I would invite Curtis to my private shoots, but it got to the point where I would get calls from shooters who would contact me in advance to see if Curtis was coming. They would flatly refuse to go if he planned to be there… and these were people who got along with everyone. They had vast NFA collections and were respected by everyone. I finally had to tell Curtis that he could no longer come. That essentially terminated our relationship.”

Few Friends, Lots of Money

The tensions also were having their toll on Curtis’ health. By the mid 1980s he suffered a minor heart attack and eventually would have two angioplasties and a triple bypass operation. He prepared a prospectus to sell the business through Smira, Oliver and Associates of Phoenix with him staying on to serve as a consultant to the new owner. There were no takers in 1983 and he again attempted in 1992 to sell off the business, but once more, no takers. By the 1990s, the addition of fresh inventory had dropped off considerably and he was mostly selling off the stock he already owned.

Curtis had a weapon collection of unimaginable dreams, hundreds of acquaintances he called friends and a profitable business (he once complained that he had to pay taxes on a $200 Thompson that he had just sold for over $20,000). But in reality, he had few close, trusted relationships. Ian Scott, a gun collector from New South Wales, Australia, provides further insight. “Curt phoned me up in 1998 and more or less summoned me over to see him. He was making up his will and told me he wanted to include me in it. About two weeks later I flew to Boise to stay with him for a little more than a week. He was on his own and after a few days I realized he was a lonely old man in this great big house full of guns that collectors would give their front teeth for and few family or friends would come near him.

“I thought of all the influential and wealthy people he had met over the last 30 years that he could have been with yet here was me, a bulldozer driver from Australia, all he could scrape up to spend part of the summer with. And, like my other holidays with him, I forgot how many times I had to bite my tongue and shut up. But despite all this, I always liked him from the first time I met him in 1980, possibly because we both grew up on a farm and, as he did, I started collecting war souvenirs at around the age of nine.”

Their friendship was cemented after Australia banned the ownership of most guns in the wake of a 1996 shooting at a Port Arthur tourist spot. Ian could have received “fair market value” for his guns, but chose instead to ship one of his best guns, a Winchester Model 1897 trench gun, to Curtis as an outright gift. Curtis would later point to this gun on his wall in his display area and reveal that no one had ever done such an act of generosity before. It deeply touched him, maybe because it was so uncharacteristic of him, at least up until the time near his death.

As indicated, his relationships with his daughters and his grandchildren were volatile and unpredictable, to say the least. One would get in his good graces only to be on the outs again for some offending remark or for some trivial affront. Be they adults or teenage grandchildren, Curtis cut no slack. As his daughter Pat explains, “He would claim that he did not respect those that would put up with his gruff, but when people did challenge him, that was the end of the relationship. This happened to my son Terrance who got along very well with Curtis for a while.” Indeed, among family, his temper was legendary. Max Rigby, his childhood friend, summed up the situation, “We know he had a heart. You could still dig down and find it; but I think a lot of people put up with his temper because of his toys and his money.”

He did, however, start to build a relationship with his granddaughter Michelle Earl Cruson, Steve Earl’s half sister, which lasted until his death. Michelle was excited about learning to fly and her grandfather enthusiastically bought her a 1946 Cessna 140 and helped her with flying lessons. She commented, “He was very protective and specified who could instruct me. Grandfather also gave me a gun and insisted I obtain a concealed weapons permit. Once he went so far as to hire a private detective to investigate one of my past boyfriends. I thought it was cute. I had a great respect for my grandfather.”

Michelle continues, “I knew he had a reputation for being strong-willed, I suppose that is an Earl trait. My husband says I have a head like titanium at times. However, Grandfather had a heart of gold even with that gruff exterior. Sure, he made me cry at times and I sometimes did not understand him, but we clicked because we shared common interests such as flying, scuba diving, and we both loved nature. Every visit was like an enchanted adventure. Flying into and fishing together at Johnson Creek, Idaho, we caught our limits, and when prospecting in Yellow Pine, Idaho, we found gold. To me these were magical times.”

Probably his closest male friend was Gary Christopher, a nuclear engineer by profession, a pilot and a writer for aviation magazines. Some say that Gary was, in essence, the adult son that he never had. In addition, there were the previously mentioned Chuck Olsen and Mike Todd.

He also had two women friends that lasted for decades. Some, such as his granddaughter Michelle, were mostly familiar with Kay. But many knew Clare Wolf, his close companion of nearly 30 years who would accompany him to key family functions. But in the very end, this relationship was terminated suddenly and cruelly.

How were they able to get along with him where few others could? Gary Christopher provides some insight. “I had listened to so many of Curtis’ stories of him bitching about customers, business associates, dealers and others, that I quickly recognized that under no circumstances could I have anything remotely resembling a business relationship with him.” Olsen recognized the same restrictions, “You just could not get sucked into any type of deal. I tried once on a trivial deal involving some Thompson drums and immediately recognized this would only lead to disaster.”

There were a few other close friends, but these just mentioned were the ones that were there with him, literally, to the very end. He could “squeeze a penny until it cried,” as someone once said, but he could also be generous in the extreme at the same time. If the stars were all aligned in perfect order, and if you had the personality and skill to help keep these aligned, Curtis could be an absolutely wonderful, fun person to be around. (Author’s note: My wife once had dinner with him and a group of friends and found him to be absolutely charming and funny.)

The Quest for a Legacy