By Vittorio Vaglio –

In 1918, it was clear that the Italian Royal Army needed an automatic rifle. Though the various proposed projects seemed peter out, except for the Revelli OVP carbine issued by the Italian Army Air Corp. But things would change by the end of that year.

Under the direction of engineer Tullio Marengoni at the Pietro Beretta firearms factory, a prototype submachine gun was built. It was stamped “RE”, Regio Esercito (Italian Royal Army), serial number S1787, and was based on the Villar Perosa model 1915 submachine gun. It featured a fire rate delayer and a little button, which, when held with the thumb during operation, allowed the weapon to fire in fully automatic mode at about 300 rounds per minute.

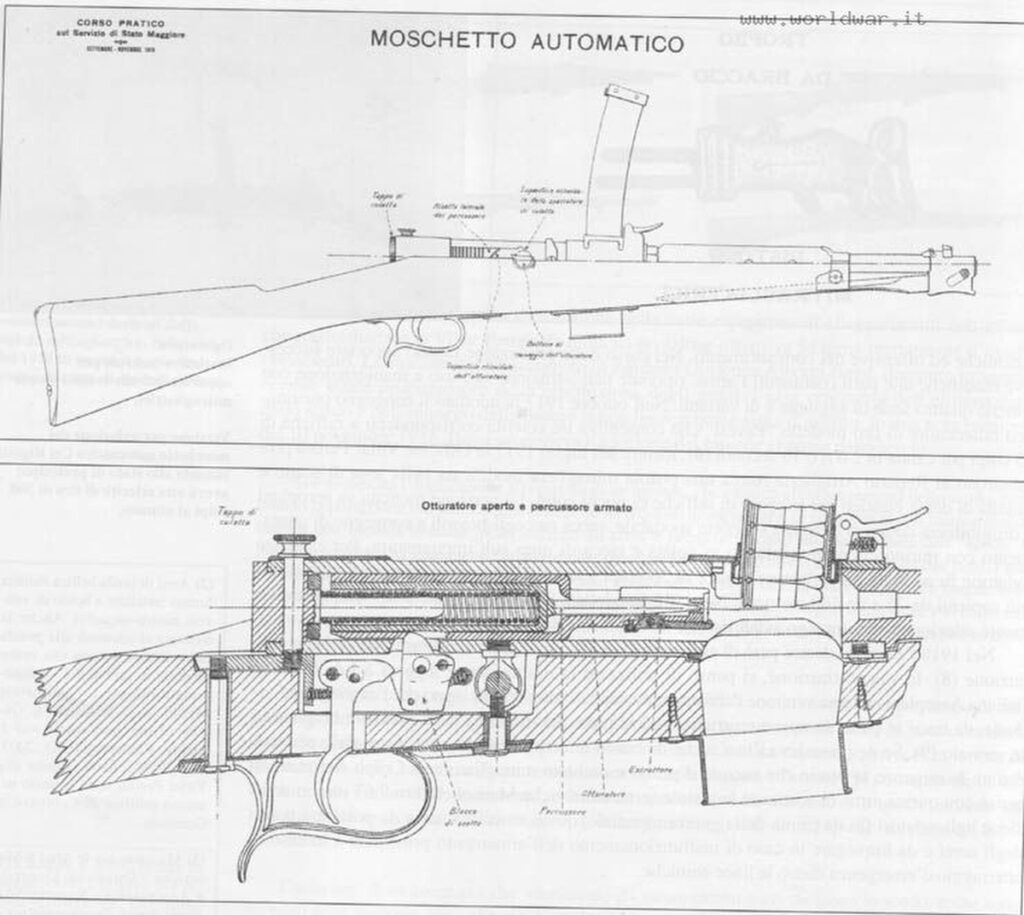

Later, a new, more successful product was made starting in September 1918 at the Pietro Beretta firearms factory. The project was under the direction of engineer Marengoni, under the direct observation of Pietro Beretta, president of the firearms factory and with the cooperation of Lieutenant Colonel Abiel Revelli himself. This self-loading carbine, as it would be called today, was mass-produced for the Italian Army and built using different parts from other distinct firearms, probably to save material during the ongoing war.

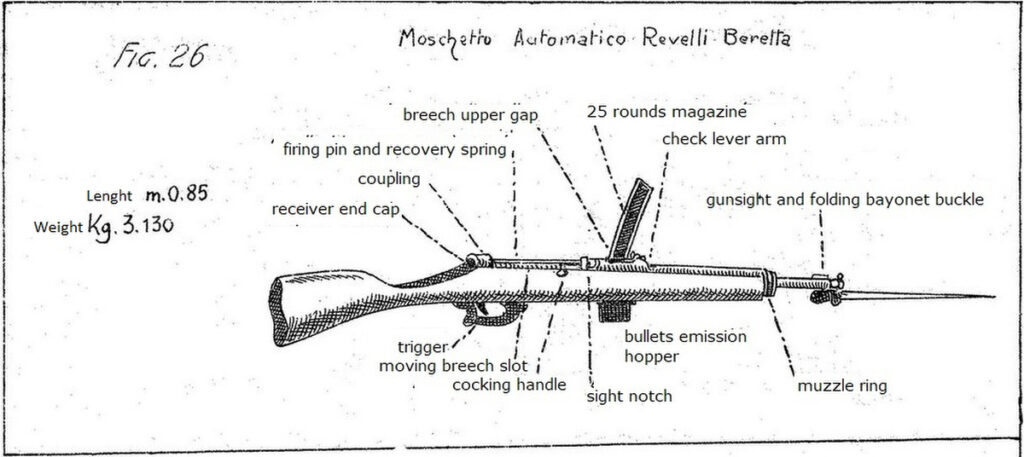

This new automatic rifle, produced by Beretta and called the model 1918 semiautomatic carbine was made using designs and parts of some Italian weapons that were in service with the Italian army at the time, such as the trigger guard of the Vetterli rifle, like the first prototype made with the fire mode delayer, and the Villar Perosa Mod. 1915 twin submachine gun, separated and mounted on the wooden stock of the Italian Carcano M91 carbine, including its cavalry bayonet. The original M91 cavalry bayonet was triangular shaped, foldable, and exchangeable. But, on this new self-loading carbine, its blade was reduced to 25cm to adapt to the dimensions of the new barrel.

This self-loading carbine was 85cm long. Like the Villar Perosa, it fired 9mm Glisenti rounds, fed from 25-round mags, but in semi-automatic only, or short bursts, because of the addition of a trigger mechanism disconnector and that won’t allow fully automatic fire of the machine gun. Its sights were on the right side; the rear sight screwed into the bolt operating lever.

Documento N. 99 of the Comando Supremo dell’Esercito, Ufficio Ordinamento e Mobilitazione, dated 12 September 1918, with subject: “New Type of Infantry Regiment”, drafted by general Pietro Badoglio, stated that the submachine gun section is abolished in the new type of experimental battalion of the 9th Italian Army. Replacing it, says the document, would be three musketeer squads, each with two automatic muskets. Every platoon of the battalion would be made up of 37 men divided into a rifle squad, a light machine gun squad, and a squad of musketeers. The automatic firearm that came out the transformation of the Villar Perosa into an “automatic musket” never saw fighting, though, because the unit that got them was a reserve unit and operated far from the WWI front.

Some classes were instituted to train troops to use the automatic musket. Production ended on 28 November 1918. According to documents attributed to Pietro Beretta, the company made a few thousand of these automatic muskets.

Right after the conflict, this weapon, known as “moschetto automatico” (automatic musket), was given the name “moschetto automatico Revelli-Beretta” (MAR-B), according to Italian military manuals of the time. For example, in the manual: “Nozioni sulle armi portatili, sulle artiglierie e sul tiro” published by the Stabilimento Poligrafico per l’Amministrazione della Guerra di Roma, dated 1921, written by Lieutenant Colonel Romeo Mella, are the descriptions and technical specifications of every firearm adopted by the Italian Army. The MAR-B is included among the automatic firearms, along with the Glisenti Mod. 1910 and Beretta Mod. 1915 automatic pistols.

Inside the “Nozioni” (Notions) is described the history of the automatic musket in the Italian Army. This manual gives credit to the action of machine guns in battle and criticized the repeating rifles of the time, reporting them as “too much heavy”, and with “a range superior to what is needed”, and providing “the firing velocity” that is not comparable to the rate of fire of machine guns. Romeo Mella also criticized the transformation of repeating rifles into automatic firearms, affirming that it would lead to a considerable growth of their weight. He proposed as a solution the adoption of the MAR-B as the new “individual firearm of the soldier.”

The MAR-B was appreciated by Romeo Mella for its mechanical qualities but criticized for its lower performing ballistic qualities. It was reported as capable of only “intermittent firing,” which means semi-automatic; so, contrary to what some secondary sources state, it doesn’t fire in full-automatic and it is not a submachine gun. It’s probable that the MAR-B was limited to semi-automatic operation to limit the possible waste of rounds – a problem that was brought to light by the automatic Villar Perosa – because of its short, 25-rounds magazines and the way it was used in combat with short bursts provided by small pulls on the two triggers.

Unlike the Villar Perosa, the MAR-B has no safety switch. The magazine catch is an original piece different than the one present on the Villar Perosa and the sights are non-adjustable. The top of the receiver is stamped, like other Beretta’s products from World War 1, “Pietro Beretta–Brescia”. Today, the MAR-B is known as Beretta M1918, but this name seems to belong to another automatic musket chambered in 9mm Glisenti and dated 23 September 1918, that, later on, would become the Beretta M1918/30.

The forgotten weapon of the Italian Army, the MAR-B, has a quite short operational life of about nine years. This is much longer than the fielding life of the Villar Perosa, which was just about three years during WWI. The last official record of the MAR-B as an operational firearm in the Italian Army is dated 1928, almost ten years after its official adoption. On page number XXV of the “Tavole di Armi” by Romeo Mella, there’s a telegram dated 4 January 1928. It was drafted by Benito Mussolini, Chief of the Government and Minister of Foreign Affairs, to Luigi Federzoni, Minister of the Colonies e Giuliano Cora, Minister at Addis Ababa. In this telegram, Mussolini anticipates a peace treaty between Italy and Ethiopia, and brings up the possibility of selling Ras Tafari, the future emperor of Ethiopia, some thousand firearms. Among those sold were 48 MAR-Bs at the price of 100 Lire (90 USD) each, with ammunition at 0.12 Lire (0.11 USD) each. These firearms, including the MAR-B, were used during the War of Ethiopia against the Italians. A few photos of the Kebur Zabagna, the Ethiopian Imperial Guard, show the MAR-B in use by the Ethiopians.

Two photos by Istituto Luce named “Ascaro sull’attent,” (“Ascaro at attention”), dated 1936 and probably after the entry of the Italian troops into Addis Ababa, show an Ascaro troop holding a MAR-B. The photos are seen here and here. In February 1938, during the Italian military mission to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, the operation chief, Captain Alfredo D’Aria of the Ufficio addestramento dello Stato Maggiore, writes to the Servizio informazioni militare to supply firearms to the Saudi Arabians. This included a 75mm Obice da 75/13 field gun with 5,000 shells and MAR-Bs (in the text mentioned as “moschetti mitragliatori M.915 Beretta Revelli”.)

The MAR-B was fielded for a short time during WWII. One example, modified by the VNS, “National Salvation Government”, the German occupation state in Serbia, was captured by Ivan Škrlj, a Slovenian, on 14 December 1944. This modified example is today conserved at the Upper Sava Museum in Jesenice, Slovenia.

The history of the MAR-B has been hidden in the shadows of small arms history and sometimes mystified as the first submachine gun design that anticipated the German MP 18/I. The MAR-B, if analyzed in depth, turns out to be very relevant in the history of small arms. In fact, it’s one of the first individual firearms to be used in an assault role, mass-produced, and adopted by an army.

This self-loading carbine was a weapon of the Italian Army, a fact which history has almost forgotten, favoring more spectacular stories, but those were all fantasies, in the end. The primary sources of the Italian Army and official manuals tell a much different reality, one that is truer and more reliable.