By Michael Heidler

The First World War changed the world. Never before had such major progress in military technology been achieved in so short a time. It’s no surprise that the end of the war did not bring a decline in demand for military goods, but rather a worldwide pursuit for more effective weapons and ammunition.

The development of automatic weapons was still in its infancy, but the results achieved at the front spoke for themselves: machine guns were indispensable in a modern war. The same loomed ahead for submachine guns, but they came too late to show their full potential in combat. After the war was lost, an ongoing development of weapons technology in Germany was inconceivable. The Reichswehr was reduced to 115,000 men (including Navy), conscription was abolished and all military schools were closed. But it wasn’t only the loss of sales that caused trouble. The victors claimed high reparations payments and dismantled German machinery. The well known company Mauser had to sell 1,500 machines to the Czech Republic and a further 800 machines to Yugoslavia. The production program was reorganized to machine tools, automobiles and other civilian products.

The once mighty German and Austrian arms industry was economically depressed – and foreign companies sensed their big chance to fill the gap in the international arms business with their own products.

The Patronenfabrik Solothurn AG

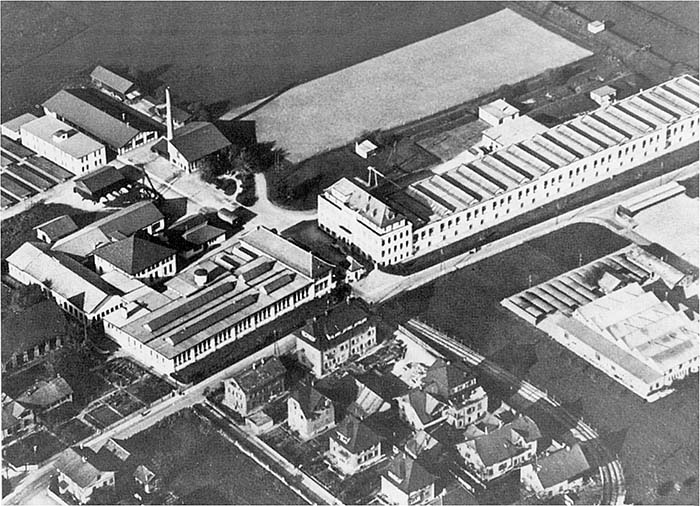

Even in Switzerland there was optimism: On March 3, 1923 the “Patronenfabrik Solothurn AG” (cartridge factory) was founded in the canton of Solothurn. For the headquarters, the vacant factory building of the liquidated watchmaker Moderna AG was chosen. Remarkable from the beginning is the rapport of the Patronenfabrik and the Metallwerke Dornach AG, which itself had produced large amounts of cartridge cases in World War One. All three founders had to do with the Metallwerke: Georg Stadler was its director and Arthur Erzer and Jules Bloch delegates of the board. In addition, the board of directors of the Patronenfabrik included Hermann Obrecht (chairman of the board of directors of the Metallwerke), Oscar Frey (director of Schweizerische Industrie-Gesellschaft AG, “SIG” in Neuhausen) and Hans von Steiger (former director of the disbanded Deutsche Waffen und Munitionsfabrik AG “DWM” in Berlin).

The Dornach metal works, suffering from the poor order situation, served as the sole supplier for unwrought cases to manufacture cartridges at the Patronenfabrik. Thanks to this order the crisis could be overcome. In addition to the Metallwerke, also the SIG Neuhausen company was financially involved in the Patronenfabrik. Common distribution channels could be established.

The business went well and the Patronenfabrik prospered. Numerous orders from South America, Turkey and the Balkan States were followed by a large order by the Swiss army of more than 10 million rifle cartridges GP 90/23 (caliber 7.5 mm). By 1927, the factory was expanded and the workforce increased to almost 400 employees.

The Crises and the End

During the 1920s, the ever-increasing competitive activities put the Patronenfabrik slowly but surely under pressure. Many Austrian companies such as Steyr, Böhler or Hirtenberger broke out of the restrictions of the Treaty of St. Germain and resumed the production of weapon parts and ammunition. Customers were found in the thriving Austro-fascist Home Guards. This competition from Austria and the Belgian Fabrique Nationale d´Armes de Guerre “FN” from Herstal made life difficult for the Patronenfabrik. The Swiss could not compete in price and suffered from an increased drop-off in orders. In particular, Hirtenberger did everything to knock out the annoying competitor from Solothurn. Deliberately, offers were calculated below cost, only to negate the chances of the Patronenfabrik to win the contract.

The beginning of the end came in 1926: The Dornach metal works, as the largest shareholder, decided to sell off its entire share in the Patronenfabrik Solothurn. The exact date is unknown, but until June 1928 all shares were sold in equal shares to: 1. Fritz Mandl (owner of Hirtenberger cartridge factory), 2. Patronenfabrik Dordrecht, Netherlands (subsidiary of Hirtenberger cartridge factory), and 3. Fabrique Nationale d´Armes de Guerre “FN” in Herstal

Soon after this deal, FN resold their share to Fritz Mandl. Now the Patronenfabrik Solothurn was completely in the hands of the competitors – and they gave short shrift: The cartridge factory was shut down, dismantled and the machines divided up between the two ammunition factories in Hirtenberg and Dordrecht. The former director Hans von Steiger went to the French company Manufacture du Haute Rhin “Manurhin” in Bourtzwiler/Alsace as a technical director.

The Rheinische Metallwaaren- und Maschinenfabrik Comes Into Play

The Austrian manufacturer Fritz Mandl was a shrewd man. After World War One he had built up a new ammunition factory in Dordrecht (Netherlands) to avoid the Inter-Allied Control Commissions and now he forged out plans for building up an additional arms factory. The end of the Patronenfabrik Solothurn afforded a suitable opportunity for him – only some potential investors were missing.

In December 1928, Fritz Mandl and Hermann Obrecht visited the Rheinische Metallwaaren- und Maschinenfabrik AG in Dusseldorf – but not alone. Three representatives of the Ordnance Department of the Federal Military Department (KTA) followed their invitation. It was at this meeting to primarily show a new semiautomatic rifle from Rheinmetall (the Heinemann Selbstladegewehr 28 in caliber 8×42.5mm), which should be made tempting for the KTA. If the Swiss Army would introduce this rifle, the planned arms company would have had a right to exist. Although it was agreed with general manager Hans Eltze that the army should receive three rifles for testing, no further negotiations followed. This was due to Mandl’s bad reputation, because the head of the KTA too well remembered the abasement of the Patronenfabrik Solothurn caused by him. With such a person no business might be done.

At the same time, Rheinmetall was still looking for an appropriate location in a neutral country to re-start the development of infantry weapons and production of prototypes for testing. As one of the 33 officially permitted arms manufacturer by the Inter-Allied Control Commission in the German Reich, Rheinmetall was only allowed the development and manufacture of guns through 17 cm caliber, gun carriages, armor plates and hydraulic equipment.

It didn’t take long until Mandl and Rheinmetall agreed on cooperation. On April 6, 1929, the Rheinische Metallwaaren- und Maschinenfabrik AG and the Waffenfabrik Solothurn AG signed an agreement in principle that regulated the future cooperation. Apparently Rheinmetall was in great hurry, because the new company “Waffenfabrik Solothurn AG” was in the first place officially registered in the commercial register on June 27, 1929, almost three months later. And in the time between, Mr. Mandl sold about half of its shares to Rheinmetall so that except for Rheinmetall only Mandl’s Hirtenberger cartridge factory still owned a little share of 10%. The assumption that Steyr was said to be involved in the new arms factory could not be confirmed yet. Six months later, Rheinmetall opened his construction office “Butast” in Moscow as a part of the secret cooperation (with support from the German government). But the projects in the Soviet Union only concerned large equipment such as artillery and armored fighting vehicles.

After the war some German companies had managed to defect to neutral countries and set up branches or to find cooperation partners. Rheinmetall had secretly managed to ship 23,000 tons of machinery, tools and production documents to the Netherlands, and thus to save them from dismantling. Falsely declared the boxes were stored for several years in rented warehouses in Rotterdam and Delfzyl before they could now be brought to Switzerland. They were used as basic equipment for the new Waffenfabrik Solothurn. The purchase was officially done in 1930. The head of the Waffenfabrik Solothurn were the director Hans Krebs and the technical director Maximilian Rechl. The former came from Berlin and the latter from Vienna, a fact that suggests the assumption that Krebs was the man of Rheinmetall and Rechl the man of Hirtenberger. Chief accountant was William Unkel (former operational organizer at Rheinmetall) and the management took over the German engineer Wolfenstein. Additionally, in October 1930, the two Rheinmetall general managers Hans Eltze and Dr. Ing. Moritz von der Porten got a seat on the board.

All of this shows very clearly that the Waffenfabrik Solothurn AG was in no way an independent private company, but rather a subsidiary of the Rheinische Metallwaaren- und Maschinenfabrik AG. To cover this entanglement an additional company was found: The “Rheinmetall Solo Vertriebs-GmbH”, based in Berlin. This company served as the formal owner of the shares and was the official sales-organization for products of the Swiss factory.

The Connection to the Steyr-Werke

Not only did German industry try to circumvent the restrictions of the Treaty of Versailles. The Austrian arms and ammunition factories were affected by the Treaty of St. Germain. The well known Waffenfabriks AG (since 1925: Steyr-Werke AG) was ailing at that time and had accumulated heavy debts. But end of the 20s rescue came in sight: Due to the good contacts of the Austrian Mandl, the Waffenfabrik Solothurn AG became connected with Steyr. Not many details are known about the way of proceeding, but the Steyr works were separated in two parts making vehicles and gun making. The latter one was sold to Waffenfabrik Solothurn. This way Steyr could liquidate the majority of their debts in 1930. In the same period, Steyr sold their ammunition factory in Schönebeck and their shares of the Sellier & Bellot AG to the Hirtenberger Patronenfabrik.

On November 29, 1930 it was ready at last. In the city of Solothurn the foundation of the “Steyr-Solothurn Waffen AG” with headquarters in Zurich and headed by general manager Hans Eltze took place. And many familiar names could be found on the board again, such as Fritz Mandl, Moritz von der Porten or Paul Götzel (head of the administrative board of the Steyr-Werke AG).

From now on, in Austria and Switzerland it was diligently designed and produced. Only the final assembly and zeroing of weapons from Steyr were done in Solothurn, since the export of complete weapons was prohibited. However, shipping of components and parts could be done in a more lax way. As the sole supplier of ammunition, the Hirtenberg subsidiary in Dordrecht was chosen. The technical progress was unstoppable and now it was important to keep pace with the international competition.

The Steyr-Solothurn Waffen AG

As already mentioned, the former machinery of Rheinmetall was used as the basic equipment of the Waffenfabrik Solothurn. And since Rheinmetall had already secretly expedited the construction of new weapons in Germany, it only took a few months until the first models were ready for production at Solothurn.

The model designations, e.g. S1-100, were based on a defined scheme. The upper-case “S” at the beginning stands for “Solothurn” and the “1” is the model number. The following multi-digit number was used to distinguish the different stages of development. For still unknown reasons a few models got a “T” instead of the “S”. The first models ready for production were:

- submachine gun S1-100

- machine gun S2-100

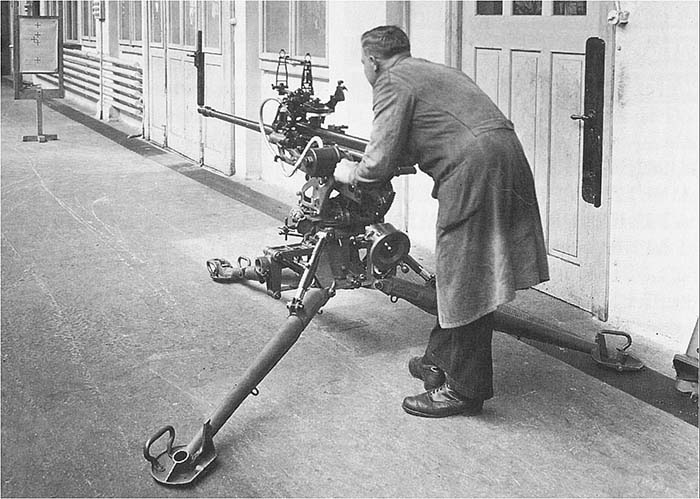

- 2 cm machine gun S5-100

In 1899, Rheinmetall had acquired a financial interest in the newly founded “Munitions- und Waffenfabrik Sömmerda AG” (former Dreyse’sche Gewehrfabrik) and two years later the company was taken over completely. There Rheinmetall produced infantry weapons, cartridges and artillery fuzes for the German Army and for export, but had to switch over to civilian products like typewriters and calculators after the lost war. The factory at Sömmerda prospered and till 1929 grew up to be the largest German manufacturer of drive shafts and joints for the automotive industry. Despite this good current business, a small team was already developing new weapons in secret again. Among them, a certain Louis Stange, which later would become known as the father of the MG34 and the paratrooper rifle FG42. Louis Stange (1888-1971) worked at Sömmerda from 1907 to 1945 as a design engineer, where he finally became the head of the weapons test workshop. And now, in 1930, the results of all this work could be brought to life in the Swiss town of Solothurn. Ahead of all this was the S1-100 submachine gun, which was based on a design by Louis Stange with the internal designation “MP20” and which was finally introduced as the MP34 in the Austrian military. After the Anschluss of Austria (Österreich) to the German Reich, the submachine gun got the foreign weapons designation MP34(ö).

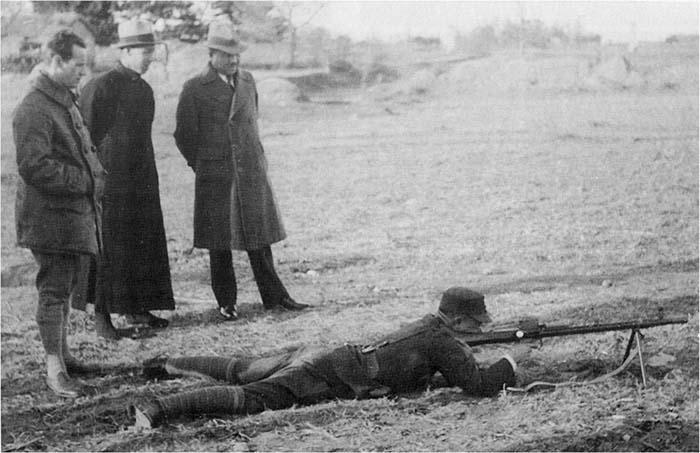

The Waffenfabrik had a good start, and the S2-200 light machine gun was a commercial success. This was a finished Rheinmetall project of an air-cooled magazine-fed machine gun with the internal codename “Söda-MG” (formerly known as “Rh29” (see SAR Vol. 14, No. 2, Nov. 2010), which was immediately moved from Sömmerda to Solothurn and shortly thereafter was manufactured there as “Leichtes Maschinengewehr S2-200.” Austria ordered in early 1930 about 3,000 pieces (MG30) and Hungary at least 1,250 pieces (MG31) – despite the ban on exports to these countries. In addition, there were also 250 machine guns S5-100 sold complete with gun-carriage. Another order for 47 machines guns plus accessories was placed by El Salvador and another 50 were sold to China in January 1932. The U.S. Army imported one S2-200 for testing purposes in 1936 and also Great Britain bought a gun in .303 caliber, along with the lightweight tripod S7-300 “Heuschrecke” (grasshopper), the predecessor of the later well-known MG34/MG42-tripod.

But no matter how good the sales were developing, so debilitating were the internal personnel problems of the Waffenfabrik. In the early years there were constant changes in the staff of the management level. Operating manager Wolfenstein and director Rechl left the company in 1931, director Hans Krebs moved to Steyr in August 1932 to take better care of the Steyr arms factory. In October 1933 von Porten and Mandl left the administrative board, followed by Hans Eltze on March 28, 1934. After only three years, hardly anyone of the old team was still on board. And the company was facing stormy waters because there was a lack of subsequent orders. After Germany’s withdrawal from the League of Nations and the Geneva Conference on Disarmament (October 14, 1933), and the reintroduction of the general conscription in March 16, 1935, the days of the Versailles Treaty were numbered and the restrictions of the armament industry annulled. The subsequent equipping of the newly created Wehrmacht finally brought the long-awaited boom and a generous support of many developments in the armament business.

No Happy Ending

After the aforementioned contracts for Austria and Hungary had been completely delivered in 1933, Rheinmetall stopped the production of submachine guns and machine guns in Solothurn. Several major contracts had now been completed under the internationally known name of the Steyr-Solothurn Waffen AG, but the production ran directly at Rheinmetall in Germany. From 1935 on, Steyr produced in Austria under license. Only the development and manufacture of anti-tank weapons had remained in Solothurn. But since it was insufficient to operate in the black, it was subsequently necessary that Rheinmetall help out the Swiss subsidiary financially, sometimes even by high remissions of debts. An audit in January 1944 showed, among other things, 24 unpaid deliveries of material from Rheinmetall to the Waffenfabrik with a total value of 198,929 Swiss francs.

It was clear for what purpose the Waffenfabrik of Solothurn had even been established: As a temporary escape location for Rheinmetall – nothing more, nothing less.

A consistent long-term development of a thriving arms factory was never really planned. Undisturbed by the Inter-Allied Control Commission, construction work took place in Switzerland and the successful sales established the brand “Solothurn” on the international arms market. For Rheinmetall this time was worth a mint. For example, all the experience made with the MG S2-200 were incorporated into the development of the later so successful MG15 and MG17. But after 1933, the Moor had done his duty. The Waffenfabrik was only kept alive by gifts of money, for the purpose of still selling original “Swiss weapons technology” – even if not a single part was made in Switzerland.

In May 1940, a major contract with the Netherlands for over 500 anti-tank guns with accessories failed because the Wehrmacht had already occupied the country before delivery. The end for the ailing company came in early 1942: The Steyr-Solothurn Waffen AG was put on the “Statutory List” – the UK’s blacklist. This list, established in 1939 after the outbreak of war, included all the companies that the British supposed to support the German Reich and its allies. And for the Waffenfabrik Solothurn as a de facto German company a place on this list was unavoidable, so it was cut off from all lucrative markets in Europe. Through stock transfers and various letterbox companies it was tried to disguise the Waffenfabrik as a Swiss company. But without success, as so easily the authorities could not be fooled. Last but not least, a large order of more than 2,000 anti-tank guns for Italy failed as the country surrendered to the Allies in September 1943. Whether a payment for the 1,500 already delivered weapons was received is more than questionable. In 1944, the last weapon rolled off the line, then the production was finally stopped.

Of the approximately 800 employees, only 200 could be kept; all others had to be dismissed. The toolmaking division was still in the development stage and too young, as it could compensate the loss of the weapons factory. The newly developed “small workshop tool set” proved to be too expensive and its sale was difficult.

In the context of trade negotiations of the Allies with Switzerland in February 1945 about the future after the war, it was decided to block all German assets in Switzerland. This meant the complete inability of the Waffenfabrik to act, and so the managers tried to make the best of a bad situation. Already on March 19, 1945 the “Werkzeugmaschinenfabrik Solothurn AG” (machine tools factory) was founded and whose shares were now fully in Swiss hands. But once again, the authorities could not be fooled. The premises were the same and in the background the already well-known managers of the Waffenfabrik pulled the strings. In January 1946, the machine tools factory was put on the list of German companies.

According to the Washington Agreement, Switzerland was committed to the liquidation of German assets. This task was executed for both companies by the accredited notary of the machine tools factory, Dr. jur. Werner von Arx. The main prospect from the beginning on was the Ludwig von Roll AG of Gerlafingen with a bid of 2 million Swiss francs. Unfortunately, the takeover failed because of the negative attitude of the Swiss clearing house, which constantly demanded new concessions and an increase in the bid of von Roll. The actual value of the two companies was in fact very difficult to estimate. Various mortgages, tax debts, vague liabilities from the cooperation with Rheinmetall and the remaining stock from the production of weapons were hard to summarize in their entirety. Also the two foundations “Wohlfahrtsfond” (welfare fund) and “Wohlfahrtsgebäude” (welfare building) associated with the Waffenfabrik had to be liquidated, which was delayed till 1949 because of legal uncertainties and disputes over the assets of over half a million Swiss francs.

It was followed by discussions and meetings with other interested parties, such as the Cartoucherie Hellenique from Athens, the Etablissement Edgar Brandt SA of Paris or the Hämmerli & Cie. AG of Neuhausen. Incidentally, the negotiations for the Cartoucherie Hellenique in 1948 were led by Waldemar Pabst. As a first staff operations officer he was involved in the counterinsurgency of the communistically Spartacist uprising in 1919. Under his command, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were tortured at the Hotel Eden and he personally did the interrogation before both being murdered. Even Fritz Mandl came back. He was mainly interested in the stock of weapons, accessories and production facilities specifically for weapons production. But a sale wasn’t achieved.

On September 27, 1950 the time had come – a buyer was found. The Gebrüder Sulzer AG acquired the property and most of the inventory of the tools factory Solothurn after lengthy negotiations for 2.1 million Swiss francs. The Waffenfabrik stayed as a tenant in some rooms, which mainly served as a storage for the still unsold weapons and parts. Despite some interested parties, among other things, Fritz Mandl again, who wanted to sell the anti-tank guns to Pakistan, no sales could be achieved. Again and again, negotiations foundered on the refusal of an export permit. Even a sale of 450 anti-tank guns to the American company Fire Arms & Ammunition failed because the Swiss authorities could not completely rule out the possibility that the weapons could be resold to other countries. The guns had already been stowed in railway wagons and had to be unloaded again.

So the time went by – until the spring of 1961, when a couple of teenagers playing in a boarded-up hut in Solothurn found some cartridges. As it turned out, the hut belonged to the weapons factory that still existed on paper. It was used as a storage for 19,000 rounds and some hundred anti-tank guns. Since a sale of the outdated weapons was virtually impossible and the Federal Council as well withdrew the old license for manufacturing and handling war material, the only possible way was the scrap yard. So all anti-tank guns were scrapped from July 19 to 24, 1961 at the von Roll AG in Gerlafingen. The cartridges were sent for recycling of raw material to the ammunition factory Altdorf.

On October 13, 1961 a chapter of eventful history was closed. The company “Werkzeugmaschinenfabrik Solothurn AG, vormals Waffenfabrik Solothurn AG” had been deregistered from the register.

Overview of Solothurn Developments:

- Submachine gun MP S1-100 (formerly Rheinmetall MP 20)

- Machine gun MG S2-100 (formerly Rheinmetall MG Rh 29 resp. Söda-MG / magazine-fed)

- Machine gun MG S2-200 (new designation of the MG S2-100 in serial production)

- Machine gun MG 30 (MG S2-200 for Austria in caliber 8 x 56 R)

- Machine gun MG 31 (MG S2-200 for Hungary in caliber 8 x 56 R)

- Machine gun MG 43 (MG S2-200 for Hungary in caliber 7.92 x 57, made at Steyr)

- Machine gun MG T6-200 (fixed aircraft-MG based on S2-200, but belt-fed)

- Machine gun MG T6-220 (pivoted MG T6-200 belt-fed from double-drum)

- MG-tripod S7-300 (“Heuschrecke”) for MG S2-200

- Machine gun S3-200 (similar to S2-200, but belt-fed)

- 13 mm AA machine gun S14-100 (magazine-fed)

- Mount S15-300 (quadruplet)

- Aircraft-MG T14-210 (MG S14-100 modified for trials)

- 2 cm machine cannon S5-100 (formerly Rheinmetall ST 5 resp. ST 52)

- Mount S9-100 for machine cannon (socket)

- Mount S9-200 for machine cannon (anti-aircraft resp. anti-tank use)

- Mount S9-300 for machine cannon (twin)

- 2 cm machine cannon S5-106 (with improved AA-sight)

- Mount S9-101 for machine cannon (socket)

- Mount S9-201 for machine cannon (anti-aircraft resp. anti-tank use)

- 2 cm machine cannon T5-150 (for use in vehicles)

- 3.7 cm AA-machine cannon S10-100

- 2 cm aircraft cannon S12-100

- 2 cm aircraft cannon T12-120

- 2 cm aircraft cannon T12-201

- Mount T13-111 for aircraft cannon (suitable for all three models)

- Submachine gun S17-100 (for tank crews / ground use possible with tripod)

- 2 cm anti-tank gun S18-100 (muzzle velocity 600 m/sec.)

- 2 cm anti-tank gun S18-1000 (muzzle velocity 850 m/sec.)

- 2 cm anti-tank gun S18-1100 (with possibility of automatic fire)

- 2.54 cm machine cannon S19-100

- Mount S20-100 for machine cannon (ground use)

- Mount S20-200 for machine cannon (light tripod)

- Mount S20-300 for machine cannon (AA-twin)

Technical Data of the Most Important Solothurn Weapons

Anti-tank gun S18-1000:

Caliber: 20 mm

Length: 2160 mm

Vo: 850 to 900 m/s (depending on the ammunition)

Rate of fire: 8 rounds/min.

Penetration: 40 mm at 100 meters and 27 mm at 500 meters

Normal fighting distance: 500 m

Max. distance of sight: 1,500 m

Weight: 50 kg (thereof 20.5 kg for barrel and muzzle break)

Length of barrel: 1,300 mm

MG 15:

Caliber: 7.92 mm

Vo: 755 m/s (with sS-rounds)

Length: 1,078 mm

Rate of fire: 1,000 rounds/min.

Weight: 10.6 kg (less double drum)

MG S2-200:

Caliber: 8 mm (8×50.5 R)

Vo: not known

Length: 1,172 mm

Rate of fire: 600 rounds/min.

Weight: 9 kg (empty)

Magazine: 25 rounds (curved)

MG 30 (S2-200):

Caliber: 7.92 mm

Vo: 755 m/s (with sS-rounds)

Length: 1,162 mm

Rate of fire: 550 rounds/min.

Weight: 9.5 kg (empty)

Magazine: 30 rounds (curved)

MP 34(ö):

Caliber: 9 mm

Vo: 380 m/s

Length: 850 mm

Rate of fire: 450 rounds/min.

Weight: 4.25 kg (empty)

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V17N3 (September 2013) |