By Michael Heidler

When it comes to weapons and the name “Ingram” is mentioned, one usually thinks of the notorious MAC-10 which is well-known from action movies. But until then it was a long way and much of Ingram’s history is little known. With his early submachine guns, he achieved only moderate success. As well, with the set-up of a production facility in Peru.

As in many countries, surplus military weapons were available at reasonable prices in the United States in the early post-war years. During this time, the entrepreneur and amateur gunmaker Gordon B. Ingram tried to gain a foothold in the competitive arms market with a cost-effective submachine gun. In May 1949, he founded the Police Ordnance Company (POC) based in El Monte, California. As the name implies, the weapons were intended for police forces and other armed state organizations. With production maturity of the first submachine gun, the company relocated to Los Angeles.

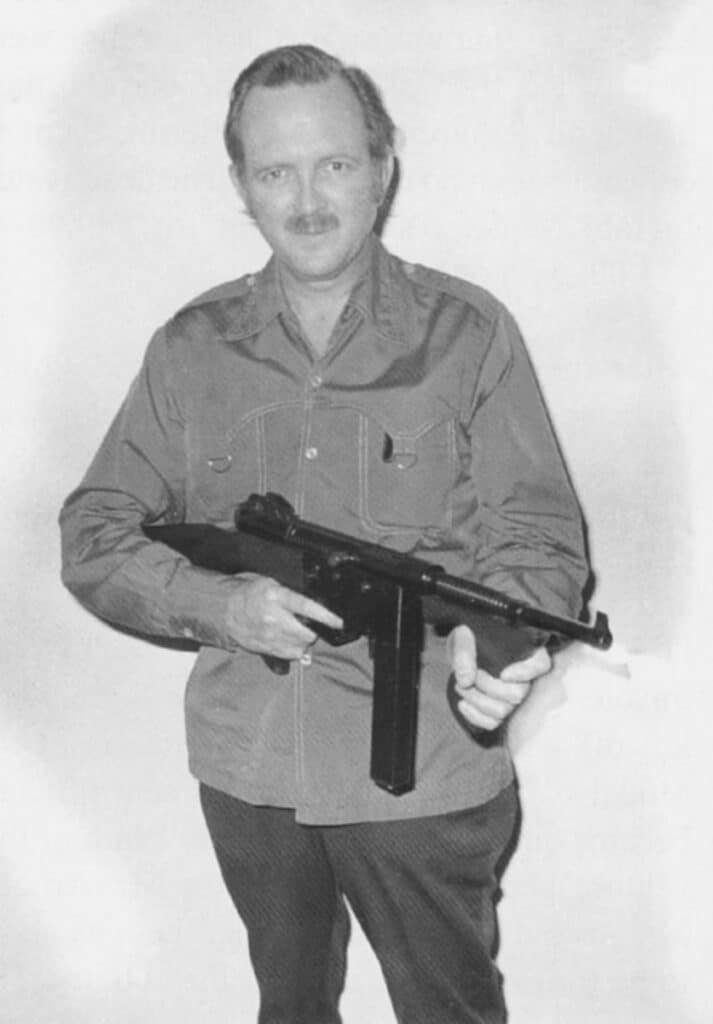

Ingram’s “Model 6” looks like an MP Thompson at first glance. That was intentional, because for the potential customers it should be a familiar sight. In terms of production technology, however, the weapon was much simpler, and, thus, priced far below the competition. The housing consists of a steel tube with screwed end cap. The trigger assembly is in a box-shaped sheet metal housing that also forms the magazine well. The only safety option is a recess in the housing into which the handle of the cocked bolt can be hooked. The weapon therefore does not offer any special innovations. It’s blowback-operated and fires from the open bolt, in which the bolt is held fully rearward by the sear when cocked. The shooter can choose between single and fully automatic fire, depending on how far the trigger is pulled. The weapon was offered from 1949 in three configurations: The “Police” version had a wooden foregrip like that of the Thompson 1928 and a barrel with cooling ribs, the “Guard” version, however, a plain wooden forearm and a heavier barrel without cooling ribs. The “Military” version in turn had additional protected sights, eyelets for a carrying sling, and a 10-inch spike-shaped bayonet, which was stored inside the forearm in reversed position when not required. Ingram considered drum magazines to be too complicated, which is why he offered only a box magazine for 30 cartridges.

The Police Ordnance Company was able to sell a larger number of the Model 6 in various designs until 1952. But the big commercial success never came. Even the improved Model 7 with manual fire selector sold badly. Gordon Ingram had actually speculated that the simple design would make his weapons attractive, especially for smaller states with lower budgets. But only the Cuban navy and the Thai army bought a small number of weapons.

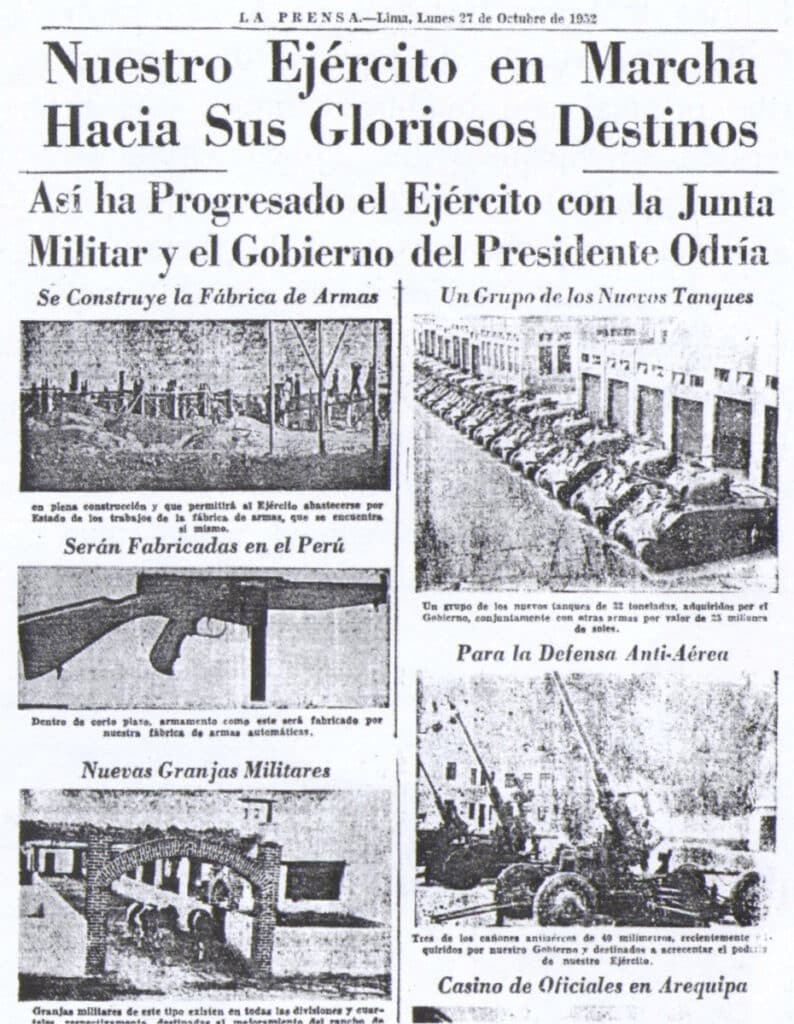

Looking for more customers, the POC salesman R.B. Morten established contact with the Peruvian government. After the war, Morten studied at the University of San Marcos and now had good connections with businesspeople and government agencies in Peru. The Peruvian army had great interest in Ingram’s submachine gun. Soon after the presentation of the weapon, the idea of a domestic weapons production came up. The Peruvian government drafted a procurement plan with the military leadership and, after brief negotiations with the Police Ordnance Company, represented by Wilson Sologuren Perez, a contract was signed in 1951: the first 500 weapons were to be manufactured by the POC in Los Angeles. Another 1,500 weapons were then to be made by Fabrica de Armas Los Andes S.A. in the Peruvian port city of Callao. Until then, the POC would get all the necessary tools and machines and import them to Peru. In addition, the POC was responsible for setting up the factory and organizing serial production. Peruvian workers had to be instructed in the operation of the machines and the technique of the weapon’s manufacture. The weapon design corresponded to the Military Model 6 in.45 ACP, but with slight adjustments to the local manufacturing possibilities. The Peruvian National Police first wanted weapons in 9x19mm, but the military’s interests took precedence. According to the contract, one delivered unit included a submachine gun with one 30 round magazine, a woven fabric sling, and a bayonet. The latter was practically unsuitable for a fight, though it may rather have served to intimidate demonstrators and insurgents.

The price per unit for the weapons to be manufactured in Los Angeles was agreed at $100. This included the packaging in wooden transport crates, which were lined with zinc for possible long-term storage in the South American climate. For the weapons to be produced in Callao, the price per unit was 1,000 Peruvian Soles. For mutual protection, an irrevocable letter of credit amounting to 1,500,000 Soles and a term of 12 months was deposited with a Peruvian bank immediately after signing the contract. The first third had to be paid after arrival of all machines at the factory. Within a period of 120 days, serial production should start and after 750 manufactured weapons, the second instalment was to be paid. By the payout of the last installment, the remaining 750 weapons had to be completed. Overall, the deadline for the contract was eight months from the start of series production.

The other points of the contract related to the time afterwards. Thus, the capacity of the factory should be designed for the possibility of at least 1,000 weapon-per-month follow-on production. In addition, the construction of a cartridge factory was planned. The Police Ordnance Company had to advise on this project from planning to commissioning. The Peruvian government reserved the right to export the weapons and ammunition produced in Peru to any other country except the directly neighboring countries of Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, Bolivia, and Chile.

One interesting aspect is security: the Peruvian government was responsible for protecting the entire factory, administrative buildings, test shooting range, and other facilities. The costs of police and possible military operations were not allowed to be charged to the Police Ordnance Company. In case of war, the POC had to concentrate fully on the production of submachine guns and neglect all minor work.

Gordon Ingram personally traveled to Peru and spent over a year completing the assignment. The U.S.-made weapons were delivered quickly, but then the first problems arose. Ingram had determined the necessary machine requirements, but the import company supplied machines that partly did not correspond to its description. For example, instead of the versatile, easy to maintain sine bar rifling machine, a far less suitable broaching machine was used, whose broaches, after wear or breakage, could only be obtained at a high price from a particular company in the United States. And Morten’s Peruvian partner in Lima suddenly confronted him with an unjustified $5,000 sales commission claim. The case came to court in Los Angeles and after a short negotiation was decided in favor of the POC. But the loser fought back – he used a feud between Peruvian President Manuel Odría and the Minister of War to influence relations against the Police Ordnance Company. Shortly before the completion of the last run of weapons, Ingram received a letter out of the blue telling him that he was not going to be paid for his last month’s work. A reason was not mentioned. But Ingram sensed that serious trouble was brewing and left Peru shortly thereafter. The contractually guaranteed last instalment was never paid.

Gordon Ingram had not become rich through this deal. Also, sales in the U.S. continued to be very low. At the end of November 1954, the Police Ordnance Company went out of business. A former colleague, John Arnold, bought (in cooperation with the National Ordnance company) all the machinery and the weapon parts in stock. He immediately traveled to Peru and visited the factory Los Andes. He probably hoped for new business relationships, but nothing came of it. Irritated by his unexpected appearance, the police told him to leave the country immediately or he risked arrest. This concluded the last chapter of Ingram’s adventure in Peru.

Overall, the Fabrica de Armas Los Andes produced about 8,000 submachine guns in .45 ACP. The 9mm version requested by the police never went into production in Peru. All weapons show the Peruvian crest behind the ejection port on the top of the receiver and differ in some details from the American model. While the Model 6 from U.S. production is available on the collector’s market today, the Peruvian model is quite a rarity.

Ingram Model 6 Technical Data:

| Caliber | .45 ACP |

| Length | 762mm (30.0in) |

| Length of barrel | 228mm (8.9in) |

| Weight (unloaded) | 3,3kg (7.3lbs) |

| Magazine capacity | 30 rounds |

| Rate of fire | 600 rounds/min |