By Michael Heidler –

Since the campaign in the East, despite great initial successes, did not lead to a rapid defeat of the Red Army, the German forces used more ammunition than originally planned. Stockpiles shrank alarmingly and the arms industry had to resort more and more often to inferior raw materials or substitutes – such as “Nipolit”.

In August 1942 alone, the total ammunition consumption of the ground forces on the Eastern Front was 143,624 tons, or over 4,600 tons per day. While consumption was steadily increasing, the shortfalls in ammunition production due to bombing damage and lack of raw materials were becoming painfully apparent. As an example, the light field howitzers fired over 3.6 million rounds in August 1943, while only 2.8 million rounds could be supplied. The General Quartermaster of the Army noted: “If the heavy fighting in the East continues, the ammunition supply can no longer be guaranteed.”

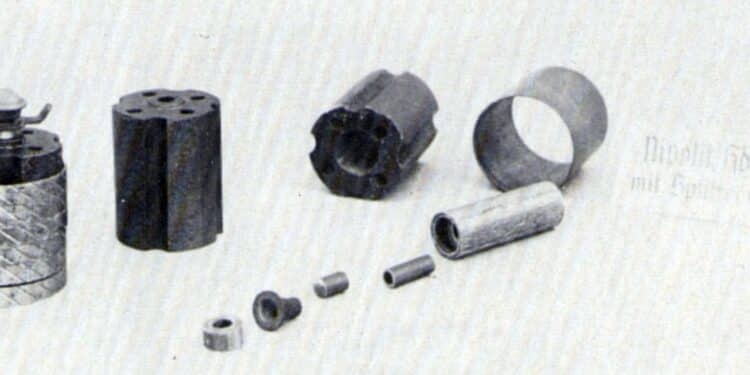

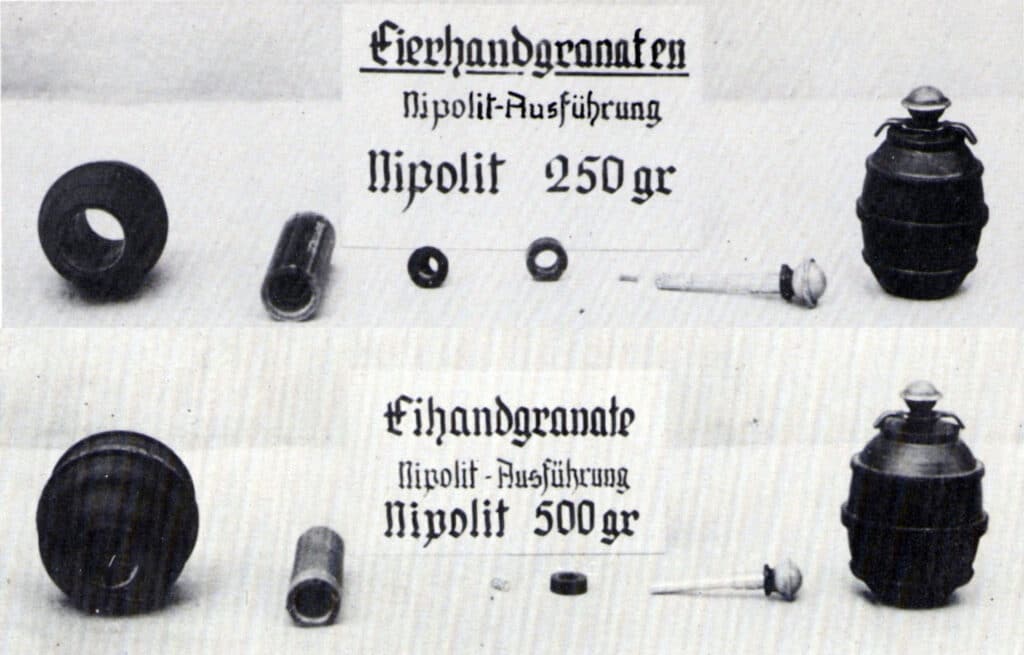

During these difficult times, Dr. Erich von Holt at the Westfälisch-Anhaltische Sprengstoff-Actien-Gesellschaft (WASAG) developed a solvent-free explosive using powder from emptied shell cases (mostly captured ammunition), delivery remnants, and cut-off waste. The end-product obtained from this residue recycling, consisting of 25% nitropenta, 25% diglycol, and about 50% nitrocellulose, was given the designation “Nipolit”. It was thermoplastic deformable, had high strength, and could be machined mechanically without danger. In particular, explosive devices, such as hand grenades, could be formed without a metal coating.

The Waffen-SS also became aware of this new explosive. At a meeting in November 1942 between the Ammunition Commission and the SS-Waffenamt (weapons office), represented by SS-Oberführer Heinrich Gärtner (head of the office) and SS-Oberführer Otto Schwab (head of the technical office VIII for research, development, and patents), about current developments, Nipolit hand grenades were also a topic of discussion. The SS was working on a hand grenade impact fuse which was ‘foolproof’ and which also couldn’t go off unintentionally even if a wounded soldier let it drop out of his hand. In Germany, only friction fuses had been used thus far. The grenade had to be thrown as soon as the fuse was activated, whereas foreign models with safety lever, like the ones used by the Americans, were activated during flight by the released spring-loaded lever after the grenade was thrown. The soldier could, therefore, hold the grenade in his hand for as long as he wanted after the safety pin was removed and wait for the perfect moment to throw it.

The SS-Waffenamt, therefore, developed an impact fuse, which was housed between two half-shells made of Nipolit. During transport, the hand grenade was secured by a safety pin. The soldier had to pull it out laterally to arm the fuse before throwing the grenade. The tests with it dragged on, but finally came to a satisfactory result.

While the Heereswaffenamt (army weapons office) showed little interest in Nipolit, the situation at the SS-Waffenamt was completely different. There, they assessed the potential of the explosives differently and tried to develop various types of hand grenades and hollow charge ammunition. Even other branches of the armed forces ordered from the SS. In September 1944, for example, the air force weapons inspector of the Kampfgeschwader 200, which is well known for various special operations, received a total of 25 Nipolit hand grenades from the Forensic Institute of the Security Police (KTI), a department of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), for a foreign mission.

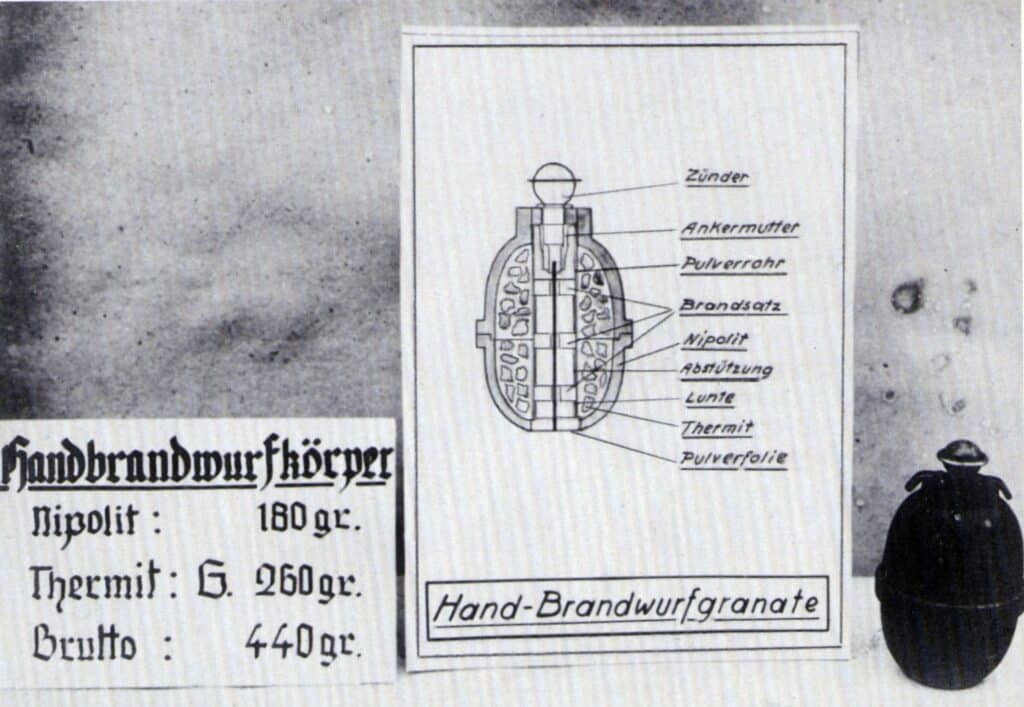

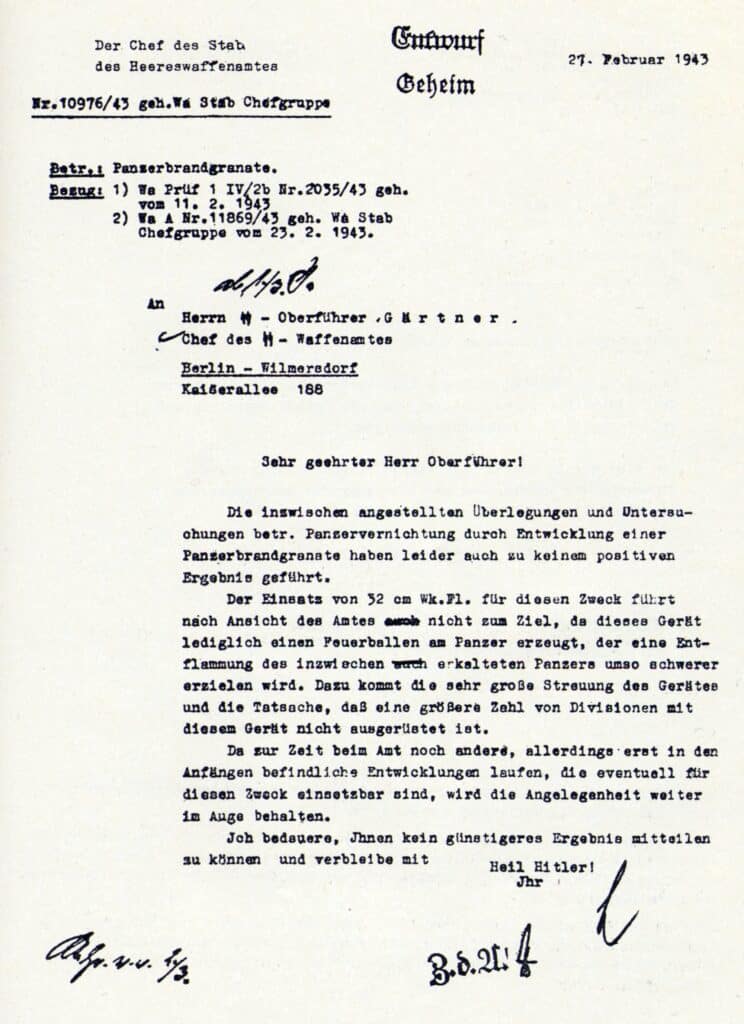

The destruction of immobilized tanks was a major problem for the troops at the front. All too often, the enemy was able to recapture and tow away those tanks that were only slightly damaged or stuck in mud. SS-Oberführer Gärtner, as the head of the SS-Waffenamt, therefore demanded a hand grenade with Nipolite casing and incendiary filling. This would have enabled the infantry to set a tank on fire and damage it in such a way that repair was no longer an option. At Gärtner’s insistence, the Heereswaffenamt took over the development in February 1943 under the designation “Brandhandgranate 4857” (incendiary hand grenade). The filling consisted of 225 cc of viscous flame oil with various ingredients. Tests in November 1944 resulted in an immediate ignition and a good incendiary effect with strong smoke development. The incendiary mass also adhered to vertical walls. So, the grenade worked technically perfectly, but it was not as easy as expected to set a tank on fire. To do so, the incendiary mass had to get into the engine compartment, which proved to be very difficult in practice and finally prevented the introduction of this type of hand grenade.

In the meantime, the composition of Nipolit had also changed. The course of the war caused the supply of diglycol to dry up and production could only continue by processing various captured powders. The output fell to about 100 tons per month. But the SS-Waffenamt remained active in this field. Fragmentation sleeves (Splitterring) made of sheet metal with predetermined breaking points were supposed to give the caseless Nipolit hand grenades a better splintering effect. In 1943, comparative tests were conducted between the SS sleeves and the different shaped ones developed by the Richard Rinker company on behalf of the Heereswaffenamt. The “Rinker Splitterringe” proved to be better because of their higher penetration rate. However, since Rinker was already working at full capacity due to other orders, the troops were to be equipped with the SS fragmentation sleeves for the time being. However, a larger series production of the sleeves was not possible at all.

On 30 November 1944, at a meeting of the Reich Minister of Armaments and War Production, it was determined that the Volkssturm should be equipped with the “Volkshandgranate 45” (people’s hand grenade). This consisted of a mixture of concrete and metal splinters (named “shrapnel concrete”) and had a good effect. SS-Obergruppenführer and general of the Waffen-SS, Gotllob Berger, in his function as chief of staff of the German Volkssturm, then ordered 100,000 of these grenades from the Preußische Bergwerks- und Hütten-AG (Preussag) in December, which were to be delivered as quickly as possible.

In order to speed up the process, SS-Standartenführer Purucker, in his capacity as commissioner for armament and equipment of the German Volkssturm, immediately appointed Dr. von Felsen, the operator of Preussag, as his colleague in the field of the application of shrapnel concrete for Volkssturm ammunition and assigned him personal responsibility for the control and development of these types of ammunition.

But rapid production was not successful for the time being. There was simply a lack of necessary cement. Even the simplest raw materials had become a scarce commodity. The production requirement would have been 900 tons per month, but by the end of January 1945 the total stock amounted to a pitiful 200 tons. And supplies were not in sight. At the Preussag cement plant in Rüdersdorf near Berlin, cement production had actually already ceased, but a cement kiln was now to be kept in operation at all costs. Coal was available for about two months of operation.

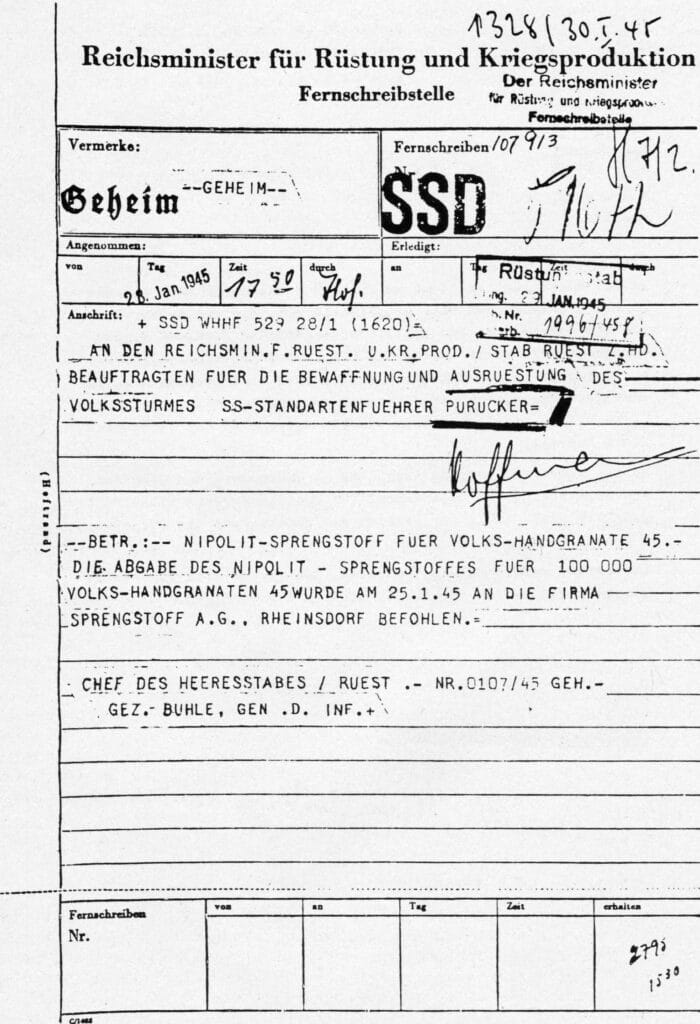

Only after lengthy negotiations was General Buhle able to obtain the provision of Nipolit as a substitute for the missing cement. He informed SS-Standartenführer Purucker on 28 January: “The delivery of Nipolit explosives for 100,000 Volkshandgranaten 45 was ordered on 25 January 1945, to the company Sprengstoff A.G., Rheinsdorf.” Unfortunately, there are no more details known about the production quantities. At least, some relics dug up along the Eastern front lines prove that these grenades were used in both variations with cement and Nipolite casing.