By Leszek Erenfeicht

The choice of the name for the brand new Czech modular battle rifle has set the expectations really high. Bren, the Czech LMG designed for the British on the eve of World War 2 lives forever as a paragon of perfection: an infallible machine gun reliable to the point of indestructibility. Will the new Czeska Zbrojovka’s Bren live up to that proud moniker?

The end of the first decade of the new millennium saw Czechs and Slovaks as the Last of Mohicans in the Unified Europe: the only country with its own creative rifle possibility to use 7.62mm caliber for the main battle long arm. The Sa-58 (Samopal vzor 58) rifle, the mainstay of the Czechoslovakian People’s Army (Ceskoslovenska lidova armada, the CSLA) has been in use since the early 1960s, when Czechoslovakia became the only Warsaw Pact country not to introduce a clone of Kalashnikov’s AK/AKM series. Despite superficial likeness, the Sa-58 had nothing in common with the AKM except for age and a cartridge. The receiver was machined, while in the AKM, the 1959 replacement of the original AK, the receiver was stamped of sheet-metal. It was a striker-fired rifle vs. hammer-fired in AKM, had a short-stroke piston, as opposed to a long-stroked Russian piston, it was fitted with a lock hold-open device operated by a magazine follower, which the AKM never had, and the locking was accomplished by a tilting wedge, not rotary bolt. Even the muzzle thread is different, and the Czech cleaning rod has female socket, where Russian brush needs a male thread. Yet there are still some around who refer to the Sa-58 as ‘the Czech AK-47’ (as if misusing the prototype ‘AK-47’ moniker for a mass-produced AK wasn’t enough abuse).

Arrested Development

However, what was modern in the 1960s, in 1970s proved to be expensive and non-modifiable. As early as 1977 a program was thus started to design a modern replacement chambered for the smaller caliber bullet. In 1977 Miloslav Fisher of the Brno’s General Machine-Building Plants R&D Center (Vyzkumne vyvojovy ustav zavodu vseobecneho strojirenstvi) or VVU-ZVS (also known as the Prototypa Brno) started the ‘Lada S’ study, to examine the possibility of re-arming the CSLA with a domestically designed and manufactured rifle, chambered for the Soviet 5.45mm round. Several years of research and preparations resulted in green-lighting the design in 1984. The study’s cover name, Lada (a popular Slovakian female first name) became the cover name of the whole program, led by Bohumil Novotny. It aimed at creating the three gun ‘family’ of unified design small arms, consisting of a subcarbine with 185 mm long barrel, an automatic rifle with 382 mm barrel and a 577 mm barreled Light Support Weapon.

The similarity of the concept to the AK-74 family consisting of AKS-74U, AKS-74 and RPKS-74 was not at all accidental. The new Czechoslovak rifles were downright Kalashnikovian in both idea and detail. The only points different were the stiffer, slide-on / slide-off receiver cover, peep-style battle-sights, and the Galil-style thumb-operated safety-selector lever, but devoid of the AK-trademark long selector lever / cocking slot cover.

The design was ready by the end of 1985; prototypes were manufactured and tested in 1986. After many failures and recoveries the third generation of these was finally approved for production in November 1989. The new rifle was then running perfect, which sadly cannot be said for the state that commissioned it. In 1989 the Communist Bloc undermined by Gorbachev’s glasnost from one side, and Polish Communists sharing power with Solidarnosc opposition movement from the other, started to fall apart in a rapid ‘domino theory’ style. Then in late November and early December came Czechoslovakia’s turn. After several days of demonstrations, the Communist Party gave way and finally relinquished power in what became known as the Velvet Revolution.

Lada: The Little Orphan

As of February 1990, the Lada system was declared fit for production, but nobody was interested in it any longer. As the Czechoslovakian program did not involve production of the 5.45x39mm ammunition (as opposed to the Polish one), conversion to the 5.56x45mm was the only logical solution – more so as the country’s ammunition provider, Sellier & Bellot in Vlasim, was already making the .223 Remington with M193-style FMJ and JSP bullets.

At first there was talk of ordering 300,000 new rifles and a tender was held to choose the system integrator and future manufacturer. The offer by Czeska Zbrojovka Uhersky Brod (CZUB), a 1936-established national arms maker, was given priority due to its rich experience in individual small-arms manufacture, including the Sa-58 and the vz.61 Skorpion machine pistol manufacture for the CSLA.

But the Army was penniless, and state (at that stage called the Czecho-Slovakia, after what came down in history as the ‘hyphen war’) was now on the verge of separation, with political fire being stoked by extremists on either side of the national divide. Fortunately the ‘hyphen war’ was the only one fought there, and everything ended peacefully, in what was dubbed the Velvet Divorce. In 1992 the history of the Czechoslovakia was over after 74 years since November 1918, when Hungary’s and Austria’s Slavic lands were united, forming the new state under the influence of Thomas G. Masaryk, who became the first Czechoslovak president. As of January 1, 1993 there were two separate states: Slovakia and Czechia (Bohemia).

Now the new rifle was in dire straits indeed – the smaller the army, the less chance to be manufactured in numbers. At the same time CZUB got privatized, and as a private enterprise it had to earn what it was to spend on the new rifle design – not just draw it on the state’s budget, as previously. For five long years the Lada program got lost from the radar – gone, but never forgotten.

Enter Mr. Findorak

After the NATO doors were cracked open with the Partnership for Peace, giving a renewed hope of the full membership soon, the NATO-caliber rifle program was once again hauled forth from the backburner. NATO-caliber – but not the STANAG magazine: this conversion would have called for a wholesale re-designing of the receiver and so was deemed too expensive. The new Lada still had an AK-74 compatible magazine – but was now chambered for the 5.56mm (even though the surviving samples are stamped ‘.223’).

Several Czech designers and companies approached CZUB in the meantime, offering other rifles instead. One of them was Ladislav Findorak, ex-Army officer, who endorsed a delayed blowback system based on Soviet Anatoli Baryshev’s designs. This was a bold proposition – a complete weapon family called LCZ, made up of the same design but different size building blocks, which put together were to give anything from automatic rifle up to a .50 cal. heavy machine gun and even a 30mm grenade machine gun. CZUB partly financed his scheme and tested the resulting weapons, but chose not to continue. Findorak then started his own company, known under the English-language name of Czech Weapons in Slavicin, but both partners parted on good terms, and CZUB was impressed with Findorak’s ability in weapon designing.

Other than Findorak, two other rifles were considered, one designed by a British team for another English-named Czech company, the Moravian Arms Company and the other option was license from Colt’s to manufacture AR-15 rifles (M16/M4). CZUB had great designs for the then struggling Colt, but all that was left of it was a less-than-spectacular Colt Z40 pistol – and the starting of the CZ-USA subsidiary, who now owns the Dan Wesson Firearms.

CZ 2000 vs. Project 805

The Army of the Czech Republic (Armada Ceske Republiky, ACR) was once again interested in the new rifle, but this interest eventually failed to bloom into contracts. The CZUB was now left with no other way than to develop the Lada and find a buyer – if not at home, then abroad, trying to capitalize on the good standing of the CZ brand and the need for modern Kalashnikov derivatives in Western chambering. But to sell abroad the Lada needed a name that was (a) sexy and (b) involved ‘CZ’ to marry it to the brand. At the turn of the century ‘2000’ seemed to mesmerize buyers and sellers alike, bringing with it a promise of the modernity – more so for what was in fact nothing more than a face-lifted AKM. Thus the CZ 2000 was born, sometime accompanied by the name Lada, sometimes not. The CZ 2000 was a name used only for PR. For in-house use, the whole ‘Army Rifle Replacement’ program was dubbed the Project 805, according to the new classification scheme, in which model numbers were assigned according to the nature of the product. Assault rifles and SMGs were assigned series 800 – that’s why the civilian-legal Sa-58 was called the CZ 858, and the 9mm silenced Skorpion prototype with a fixed stock was the XCZ 861.

The New Rifle

It was only in late 2005 that CZUB decided to go whole hog and make their own rifle anew. The Army was not yet inclined to change the battle rifle for the entire military, but they nevertheless managed to buy a batch of Bushmaster M4A3s for the Special Forces. The situation could have slipped out of hand if the Army continued to re-arm itself piecemeal, instead of a large-scale re-armament – so CZUB bolted into action. A totally new specification was drawn, finally putting the stillborn Lada to rest. The new rifle was first called the CZ XX, then CZ S805. The S stood for ‘special’ to differentiate it from regular CZ 805 (no S), being a tricked-out Lada carbine with rails all over and an ambidextrous selector lever, designed for India (but never bought).

This new design was meant to get CZUB to the forefront of the world’s rifle evolution, constituting a totally new multi-caliber modular platform – much in the SCAR flavor. There were to be two sets of building blocks, one (with ‘A’ in model designation) for three intermediate rounds (5.56×45 mm, 6.8SPC and 7.62×39 mm), and the other (‘B’) for rifle calibers – and that’s not only 7.62×51 mm mind you, but .300 Win Mag as well. Each of these could have been fitted with three lengths of barrels, to became a Battle Rifle (‘1’ designator), CQB Carbine (‘2’) or the DMR/LSW (‘3’) fire support weapon. Thus a rifle in 5.56mm would be an A1, while a carbine in 7.62×51 mm would be a B2, and so on.

Close But No Cigar

CZUB had no design resources to speedily accomplish a design like that, and so they decided to outsource the designing phase and hired Mr. Findorak again. This proved to be an excellent choice – in less than a year the rifle was not only designed, but prototypes were built and tested. This also proved unfortunately to be Findorak’s last design accomplishment, as he died prematurely in the fall of 2006, in his early 50s.

In November 2006, CZ S805 was first demonstrated to the Army’s chief of staff, General Stefka, but the Army again didn’t order any – instead they bought another batch of Bushmasters. After that, CZUB decided to go public with their new accomplishment, hoping that patriotically-inclined public would affect the military complacency. For three years the rifle was regularly exhibited during the IDET fair in Brno as well as Prague’s ‘Future Soldier’ conventions, but success proved to be elusive. The big change came upon in 2009, when finally a tender was opened for the Czech Army’s new battle rifle.

Meanwhile at the factory, the Findorak rifle design’s development had been overseen by Vitezslav Guryca, a CZUB designer since 1984, whose previous accomplishments included the CZ 97B; Czech first ever .45 ACP pistol. Testing of the Slavicin-made prototypes revealed minor problems with lock timing, trigger mechanism, buttstock, return spring assembly, and barrel change method. These teething problems were ironed-out by Guryca, assisted by the CZUB’s chief engineer Radek Hauerland, chief designer Pavel Mahdala, with Jaroslav Bachurek, Jiri Kafka and Vladimir Simek. They were also designing the whole armament subsystem around the new rifle, including a novel 805 G1 40mm underbarrel grenade launcher, as well as the 805 UN/BN bayonet.

Racing against the clock, the design team decided to curtail the modularity of the system, and press on with development of only the A platform (SCAR-L equivalent) with two barrel lengths, rifle (A1) and carbine (A2). These were initially provided in two calibers, 5.56x45mm and 7.62x39mm. The first A1 demonstrated in November 2006 to the chief of staff was a 5.56mm A1, but the first to be hands-on publically demonstrated was the A2 in 7.62mm (during the Future Soldier 2008). Later on, the program got curtailed once again – only the 5.56mm system was exhibited since then, from early 2009 on with a re-modeled upper receiver.

The Multi-Optional Rifle

The caliber exchange in the CZ S805 rifle requires changing barrel, gas system, bolt-head and a magazine well. The magazine well is a separate module of the lower receiver, connected by a T-slot and the rail and (since 2010) stabilized with a pin – the idea resembling the MGI’s Hydra exchangeable magazine well system. There were three magazine modules demonstrated so far, two for CZ’s own plastic magazines and one for the AR-15 (STANAG) magazine.

The proprietary plastic magazine is a really bulky affair, patterned after HK G36 magazines – the 5.56mm variant claims interchangeability with the German rifle. These are opaque, semi-transparent to allow quick bullet count, and fortunately do not copy the G36 integral magazine couplings. The 7.62 and 5.56 plastic magazines differ mostly in shape with the 5.56 being much straighter than the 7.62 banana. There’s even a joke about these, stating that the 5.56 is a ‘Euro banana’ (hinting at the infamous EU regulation on the shape of banana, stipulating it should be almost straight – because such shaped bananas prevail in former French Guyana), as opposed to the 7.62mm ‘real banana.’ An AKM-compatible magazine well was announced, but never demonstrated, while the factory dismisses the speculations about Sa-58 compatible magazine well being ever contemplated.

Bought At Last

In November 2009, the long-awaited tender for the new Czech rifle was organized, but despite 27 initial submissions, only two rifles were finally pitted against each other: CZ’s offer, now referred to as CZ 805 Bren and FNH’s SCAR-L, with domestic design being finally selected after a reportedly hot contest, decided by a narrow margin. The results were promulgated on February 1, 2010, and on March 18, after the FN’s Czech partner decided not to repeal the results, the ministry finally ordered 6,687 CZ 805A1 rifles, 1,250 CZ 805A2 carbines and 397 CZ 805G1 grenade launchers. Each rifle and carbine was ordered with Meopta’s ZD-Dot red dot sight and a set of BUIS, and for the special forces 1,386 ‘enhanced optical suites’ were ordered, consisting of Meopta’s DV-Mag3 daylight 3x magnifier, NV-3Mag night 3x magnifier and a DBAL-A2 (AN/PEQ-15A) laser target designator.

But before the first rifles hit the shelves of the Army stores, the military demanded several changes that arose from the qualification testing of the samples delivered as stipulated in contract by May 2010. First of all, somewhat surprisingly, the Army requested a folding-only stock instead of the factory-offered folding/telescoping stock – said to be awkward. The stock is held by a T-rail on the receiver backplate, and can be replaced any time, for any style – providing it is fitted with a proper attachment. Second change concerned stabilizing the magazine well with a pin. The third request called for replacement of the fixed pistol grip with one fitted with exchangeable backstraps, just like the ones so popular since all new pistols’ frames became plastic. Another change was introduced in the bolt head – the seventh locking lug was omitted. Initially, the seventh lug was deeply undercut by the extractor claw channel, and it could possibly crack, so it was eliminated and now there’s only six. All these changes delayed the date of the initial delivery to July 19, 2011, when the first 505 A1s and A2s with 20 grenade launchers were taken over by the Army, with 2,745 A1s and 926 A2s scheduled to be delivered during the latter half of the 2011, and further deliveries made until 2013, when the initial order would be fulfilled.

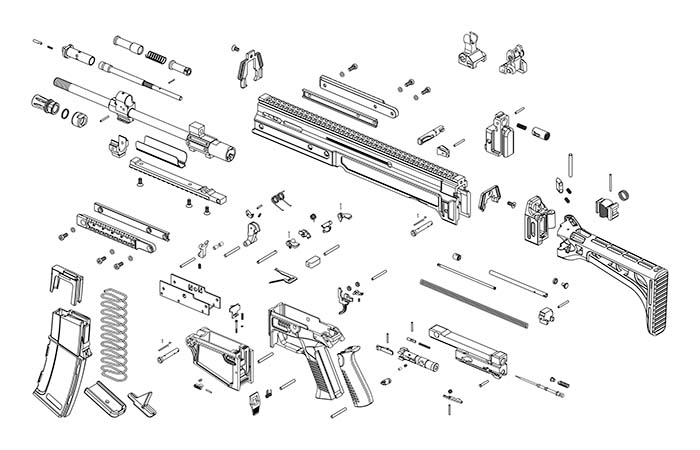

The Inner Life

The gas-operated rifle has a gas opening on top of the barrel, where gas block with bayonet attachment on the bottom is fitted. On top there’s a large ring, into which the gas mechanism is inserted. The gas mechanism consists of a one-piece gas piston (somewhat resembling the one of the Sa-58), complete with a self-contained return spring and two-stage gas regulator. The whole gas system is held in place by a lug in the form of the regulator shield. When the shield is turned to either of the two working positions, the lug stays firmly in the abutment cut into the gas block. But if the gas regulator is turned a full 180 degrees, there is a flat undercut in the shield, fitting over the top of the gas block, and the whole unit can be pulled clear for cleaning or replacement for other caliber’s set. No other procedures or tools are needed. Whoever struggled with a SCAR gas mechanism once would appreciate that immediately and immensely. The piston hits the boxy bolt carrier and makes it recoil, while the operating cam unlocks the bolt. The unlocked breech opens and the extractor extracts the spent case, while the spring-loaded rod ejector in the breech face tilts it to the right. Then the ejected empty hits the deflector, changes the rotation direction and flies clear forward and to the right. The ejection opening is far enough ahead to allow left-handed operation without the need to change the ejection direction. The recoiling bolt-carrier compresses the return spring set on a single guide rod, but not anchored rigidly in the back plate. There’s no magic at all in the operation of the CZ 805 Bren: as with about 75% of modern military rifles based on the AR-18, if you know one, you know them all. The only unusual thing is a firing pin automatic safety in the rear part of the bolt carrier – a spring loaded lever that hooks in the pin, holding it immobile to prevent AD from pin inertia. It operates just like the HK MP7 firing pin safety, being swept out of the way by the falling hammer.

The upper receiver is monolithic, with a full length Mil-Std 1913 rail running on top. The upper is machined out of a forged aircraft-grade aluminum billet, has a form of an inverted U-sectioned through, completely open at three sides. Initially it was planned to be made of polymer plastic, but during the development an aluminum ‘interim’ receiver was used, and so it remained. The sides have (each) two cooling slots and three barrel screws openings, as well as a cocking slot with rounded cocking handle inserting opening. The cocking handle can be inserted from either side, without any adverse effects on operation. The barrel screws also hold the side rails, and their openings are filled with polymer sleeves to eliminate vibration and hinder heat transfer. The ejection opening is on the right side of the upper receiver. From the rear it is closed by a back plate, from the front by the barrel assembly, and from the bottom half by the lower rail, being the part of the barrel assembly, and the other half by the lower receiver. The interesting point here is, that the lower hinges not on the upper receiver, but on the rear end of the bottom rail.

The Barrel Assembly

The barrel assembly is exchangeable as a whole unit, and resembles the one used in SCAR – at least in the mode of fixing – very closely. The locking ferrule is screwed onto the rear end of the barrel. The rear two pairs of the barrel fixing screws are screwed into this ferrule from the sides. On top of the ferrule there is a piston guide, directing it on the way to hit the bolt-carrier. On the bottom another two screws fix the lower rail to the ferrule. At approx. 2/3 length of the barrel the gas port is drilled, covered with gas block. Just aft of the gas block there is a U-shaped former, into which the bottom of the forward bottom rail screw is screwed, and into which sides fit the forward barrel fixing screws pair. The locking ferrule and this former keep the barrel free-floating as much as possible in a gas-operated gun. The muzzle is threaded for a countering nut and muzzle devices – standard bid-cage flash hider/compensator, a blank-firing-attachment or a sound moderator. To exchange the barrel one has first to field-strip the rifle (the bolt head has to be withdrawn from the locking ferrule of the barrel, and lower receiver has to be detached from the bottom rail), then to unscrew six barrel fixing screws and withdraw the barrel. It can be done in field conditions, but it is by no means a quick-change barrel. Anyway, it takes a torque wrench to reassemble it in a rigidly-regulated sequence. Whoever changed a barrel on SCAR, knows the drill.

The A1 and A2 barrels are identical save for the length and theoretically they can be exchanged freely – but in reality the Army ordered the rifles in final configuration with no spare barrels. It is then a modular system, but not an operator-configurable one. The bore is 6 grooves, one right hand twist in 7 inches.

Lower Receiver

The lower receiver is divided into two parts: trigger mechanism housing with pistol grip and the exchangeable magazine well. Both are made of polymer, connected by a T-rail and corresponding slot, and pinned. The pin can be started out by bullet point, and then pushed out with a firing pin. After the pin is out, both parts can be slid one from another and separated. In both 5.56mm magazine wells the magazine release is fully ambidextrous – by bottom lever in CZ proprietary magazine, and by buttons positioned on both sides of the STANAG-magazine well. The bolt hold open is positioned inside the magazine well and provided with ambidextrous push-buttons. Caution: these can only activate the hold-open when there’s no magazine. The release is ALWAYS by pulling on the cocking lever. This is a drawback, but Czech soldiers used the same system on their Sa-58s for half a century, and 50 years of tradition is an undisputable power in each Army. The standard magazine well is the CZ plastic magazine one, but STANAG-magazine wells are going to be provided for the Special Forces to insure interoperability and also for the future A3 LSW variant, to enable the use of the Beta C-Mag and other high capacity magazines fitting the AR-15 magazine well.

The complete lower is a swing-out affair, fixed by two cross-pins. After the cross-pins are withdrawn, there are corresponding sockets in the stock where these can be stored. Nothing new for any HK user.

The modified (M2011) pistol grip has exchangeable backstraps, also secured with a pin. Two sizes are available, standard (M) which fits most hands, and XL.

The trigger mechanism is a modified AK with a burst limiter – not much changed since the Lada, except perhaps for the flat trigger/selector retaining spring, which is another of the Sa-58 left-overs. The selector has four settings, 0-1-2-30, all within a right angle, which means that separations are diminutive, just 22.5 degrees. Pictograms are dots in two colors: white dot means SAFE, and then there are red dot(s), for single, burst and continuous fire. The lever is well within reach and moves up to SAFE, down to FIRE, just like the 1911. A possible civilian-legal variant would perhaps only have two settings, SAFE and FIRE also in a 90 degrees arc, which would be best for it. The burst setting is pointless, with the two-rounds burst – fortunately it resets itself after releasing the trigger prematurely, unlike the M4.

Pros and Cons

This author had the opportunity to check out the CZ 805 Bren at a shooting range, and the occasion, however brief, left me with several remarks to make. A 4.2 kg heavy rifle has no right to display a noticeable recoil or muzzle flip with the 5.56x45mm round, and this truth was once again proven by the CZ rifle. It takes a long burst on fully automatic to swing the muzzle noticeably, although still keeping a full magazine-dump within a torso target at 15 meters was easy – as opposed to the Sa-58. The shoulder stock is made of plastic, and by contrast seems to be weightless at all, which means the rifle is heavy on the nose. That’s not bad for dynamic sweeps, but if you keep it ready for a long spell of time, your weak hand would finally become sore. And definitely make use of the 6 o’clock rail by attaching a foregrip. If you don’t, you have to watch your supporting hand thumb position – if you utilize the cocking handle on the left side of the gun and you’re not a southpaw, that is. Again, whoever shot the SCAR, knows why – the cocking handle is reciprocating, and with bolt in battery it is very easy to place your thumb in the way, if you support the gun by magazine well. Been there, done that – you better don’t. The cocking handle stripped the half of my thumbnail in no time. Nothing you’d like to repeat, believe me, although not incapacitating. The rifle is mostly flat, but has rails all over – waiting to skin your fingers alive if you don’t muzzle them with rubber covers or wear gloves, or preferably both. All controls are within easy reach (or at least – within MY easy reach) and work quite nicely – rotate easily, but firmly keep their positions, or spring back energetically after release of the push buttons. The only drawback in that area is the safety-selector lever, with four settings within 90 degrees – that’s way too cramped. The plastic magazines are said to be interchangeable with HK G36, but fortunately omit the integral coupling devices, sticking out from their sides. Anyway, they’re still wide and big – it’s hard to believe they only keep tiny 5.56mm rounds.

The long 40-centimeter overhead monolithic rail has enough room for any combinations of sights one is likely to haul. The factory sights suite consists of a set of CZ’s own BUIS and a Meopta ZD-Dot red point sight. Whoever used any variation of the M68 CCO would be at home with the ZD-Dot, housed in as big a tube with as many protuberances as most of the M-series Aimpoints, and utilizing the same time-proven red dot reticle. By the way, it’s the Meopta who makes most of the Aimpoint lenses. Each A1 rifle and A2 carbine was ordered with a ZD-Dot. 1,386 would get an ‘enhanced optoelectronic suite’ consisting of two 3x magnifiers, one day-time, one coupled with NV device and a DBAL-A2 laser module. The magnifiers, at least the daylight model, DV-Mag3, gives a very sharp, even image. The optics are really good – but Meopta still has a thing or two to learn in tactical optics. No quick release means – so while FIBUA you have to undo a lever and take the magnifier out, unlike the Aimpoint QD pivot mount. But the prototypes had both red point and the magnifier mounted with Allen screws, so that’s an improvement over the previous version, nevertheless.

Que Sera Sera

The future of the CZ 805 is still ‘not ours to see.’ It has just begun it’s travel, and the soldiers would no doubt find many ways to give the CZUB team a reason for headaches. For some reason or other the modular rifle have in reality became a fixed configuration one – perhaps the user had not matured yet to have too many choices left. The plans are still ambitious, though, and in May 2011 the existence of the new A3 was announced – but in a little strange way. The A3 ‘soon in a theatre near you’ is a bipod-fitted LSW/DMR – that’s more or less consistent with the program. But then the CZUB announced it would be a 7.62x51mm weapon, which then should be a B3 rather, and the first version of the long-awaited B full-power round configuration. The civilian-legal semiautomatic variant of the A1 has also been hinted to, so perhaps there would also be a U.S.-market version with a 16-inch barrel – which would certainly be greeted with much interest.

| Technical Data | ||

| CZ 805A1 | CZ 805A2 | |

| Caliber | 5.56 mm x 45 NATO | |

| Length, stock folded [mm] | 670 | 587 |

| Length, stock unfolded [mm] | 915 (w/ bayonet 1050) | 782 (835) |

| Barrel length [mm] | 360 | 277 |

| Sighting radius with BUIS [mm] | 395 | |

| Width, stock folded [mm] | 112 | |

| Width, stock unfolded [mm] | 77 | |

| Rate of fire [rpm] | 700-800 | |

| Battle range [m] | 500 | 400 |

| Weight with full magazine [kg] | 4.2 | 4.1 |

| Weight w/ full magazine and 40 mm CZ 805 G1 grenade launcher[kg] | 5.8 | 5.6 |

| Magazine capacity [rds] | 30 (CZ) or 20, 30, 40, 100 (STANAG) |

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V16N4 (December 2012) |