By Terry Edwards

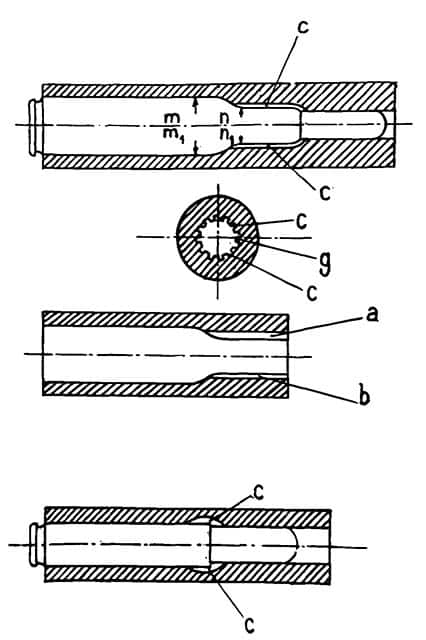

Giovanni Angelli is best known as the automotive visionary who founded and grew FIAT. Less well-known is his 1914 British Patent GB191508943A/Italian patent 8943. This covered two firearm chamber modifications. The first was making cuts in the chamber for the brass case to swell into under pressure. The brass would then have to swage back to shape during extraction, delaying the action. The second patent modification was to extend similar chamber recesses forward of the case, thus allowing gas to push back between the case and the chamber wall. This “floated” the case in the chamber and facilitated easy extraction.

As soon as Hiram Maxim invented automatic firearms, inventors tried to find novel means of operation to make their gun designs simpler, cheaper, lighter, more powerful and more reliable.

But, not only was Maxim first to harness the gun’s own self-generated force to operate it, he went about imagining and patenting every method he could think of to achieve this. Gun designers hoping to dazzle the world often found Maxim’s name already attached to almost every variation of recoil and gas operation.

Blowback is the simplest form of automatic operation. It is simple in concept and manufacture. The gun is powered by the energy of the firing cartridge “blowing back.” The case pushes the bolt back, usually against spring pressure, and energizes parts to extract and eject the spent case. The now compressed operating spring subsequently pushes the bolt forward, recharging the gun.

But, the simplicity is deceptive. Blowback is a balancing act of ammunition, bolt weight and spring strength. There are upper limits to the power. As the limits are approached, bad things start happening. Gas pressure can bulge, split or blow the case apart. The forward part of the case, being thinner than the rear, can press so firmly into the chamber it sticks and separates while the rear part moves back, often damaging the gun and injuring the user. At best, the speed of the action will become violent, damaging internal parts and spewing out empty cases at dangerous speeds. The designer can add mass and spring resistance to counter this, but these will make the gun difficult to use. The designer must then devise some means of delaying the opening of the breech until the bullet has left the barrel and allowed pressure in the case to drop. This usually means gas operation or a complex design of recoil operation.

As blowback operation is limited by the power of the cartridge, raising the safe limit can result in one of two desirable things: a more powerful cartridge can be used, or the gun can be made lighter.

Giovanni Angelli had an answer. When the Italian firm FIAT was born in 1899, Giovanni Angelli was one of the founders. By 1902, he was Managing Director and by 1920, Chairman of the Board.

FIAT-Revelli Model 1914

In World War I, FIAT was making the 6.5mm FIAT-Revelli Model 1914 for the Italian Army. The gun had extraction problems and required the cartridges be oiled to overcome sticking. In the search to improve the gun, Angelli was issued Italian patent 8943. It covered two types of chamber modifications. One was intended to delay the opening of the breech, and the other was meant to ease it.

Both were accomplished by adding grooves into the chamber. In order to ease extraction, grooves reach ahead of the case and channel gas backwards, between the chamber wall and the case, to push or “float” the case away from the chamber wall. These grooves, called “flutes,” are found in many firearms from pistols to grenade launchers.

But, extraction can also be delayed by cutting grooves into the chamber walls that do not reach far enough ahead of the case to channel gas back. Instead, the brass of the case bulges into the indentations under pressure. The distorted case then has to be swaged back down during extraction. All this creates a delay by increasing “stickiness” rather than easing it.

The expelled cases from fluted chamber guns are usually easily recognized. Some may be physically distorted by the fluting while most are simply betrayed by patterns of soot.

The Soviet Union had talented designers willing to use daring concepts. The Tokarev rifles SVT-38 and SVT-40 had chambers with flutes cut into the shoulders. Both served throughout WWII.

Vest Pistol

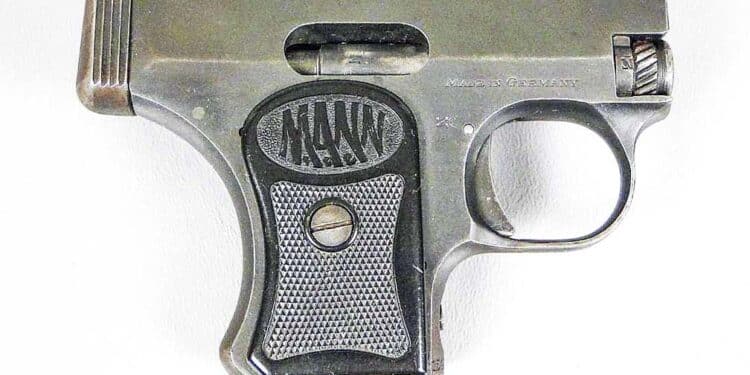

In the 1920s, Fritz Mann was a German businessman and gun designer in his family’s manufacturing firm. The “Vest Pistol” was a popular accessory, and Mann’s company was competing in the fiercely contested market. Mann needed to elevate his blowback gun above the competition.

While his gun featured a number of innovations, Mann’s 1920 German Patent 334098 describes a chamber-ring based on Angelli’s concept.

Mann cut a ring around the inner chamber wall, roughly 1mm deep and 3mm wide. When the gun was fired, the brass of the cartridge case was forced outward into the ring, only to be swaged back as blowback forced the case to the rear. The swelling and squeezing delayed the breech opening enough to allow the empty case to be withdrawn without a bulging head or separation. Mann’s firm produced two .25 ACP models, the Model 20 and Model 21. The ejected cases are clearly identifiable thanks to the ring. Because the .25 ACP cartridge is not overly powerful, the guns could digest a variety of ammunition. The gun was moderately successful, but Mann made a number of other products, allowed the gun department to languish and folded in 1938.

In the years after WWI, Angelli and FIAT revisited the troubled 1914 machine gun. Their redesigned FIAT 28 used two full-length chamber flutes to float the case and replace the original’s oiler. The new gun also featured belt-feed instead of the awkward clips previously used. For all this, the Model 28 was not a good gun. Angelli’s flutes brought better results in the Breda 30 LMG in a 7mm made for Costa Rica. Instead of the two flutes of the FIAT, it used 30 full-chamber-length flutes to ease extraction.

The J. Kimball Arms pistol in .30 carbine; a series of rings were cut into the chamber to slow extraction and the company fire-formed the brass into a “shouldered” shape. Fear of mechanical failure stunted sales.

A New Chamber Concept

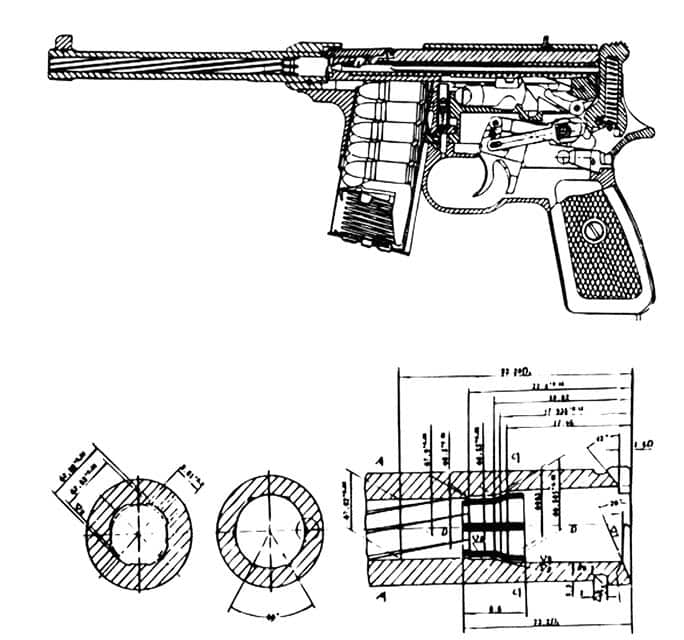

A completely different chamber concept was devised and patented by American David “Carbine” Williams between the World Wars. Colt Firearms had wanted to offer their 1911 pistol in .22 long rifle. Their first attempt was an indifferent blowback design. The next try was designed by “Carbine” Williams and used his “floating chamber.”

The inside of the chamber itself was not unusual, but the chamber was in a separate section that slipped into an enlarged and elongated chamber in the barrel. As the bullet fired, gases pushed into the gap between the front of the floating chamber and the barrel. The pressure exerted on the front of the moving chamber forced it back, transmitting enough force to function the gun. The design, being confined to the slide assembly, also meant a conversion slide could be sold and slipped onto existing 1911 lowers. Known as the “Ace Conversion,” this was a great success, and Williams designed a similar system for firing .22s from the .30 belt-fed Browning guns.

The 1932 Soviet Union used chamber flutes in their ShKAS aircraft gun to handle a special high-powered 7.62×51 rimmed round.

The Grendel P30 was designed by George Kellgren, now of Kel-Tec. It used 16 chamber flutes to achieve smooth extraction. Newer cartridges and refined design let its successor, the Kel-Tec PMR30, do without the flutes.

The Soviets next used flutes at the fronts of the chambers of their Tokarev SVT-38 and SVT- 40 gas-operated rifles. These were the first mass-produced guns with flutes and were used throughout WWII.

Over 50 years later, the Russian PP-9 KLIN version of the KEDR submachinegun appeared. While the KEDR is a straight blowback gun chambered for the 9x18mm, the KLIN has helical grooves (picture compressed rifling) in its chamber. These are designed to delay operation by its hopped-up 9x18mm PPM Makarov cartridge.

The Swiss embraced chamber flutes when they upgraded their arsenal after WWII to incorporate a series of roller-locked automatic rifles. The early SIG SAUER Stgw 57 used eight flutes in groups of two. The subsequent SIG AMT semiauto in 7.62 NATO used 16 evenly distributed flutes, and the later SIG 510 in 7.5mm and 7.62 NATO used eight flutes. The belt-fed MG 710 light machine guns (LMGs) all use 12 flutes.

The recoil-operated, belt-fed French AAT Model 52 LMG was introduced in 1952. It uses 16 flutes to aid extraction of the 7.5mm or 7.62mm NATO cartridge. The French bullpup FAMAS in 5.56 NATO is also recoil-operated and uses 16 flutes to aid extraction.

The KLIN was a version of the Russian 9mm KEDR SMG converted to the more powerful Makarov 9mm using helical chamber cuts to achieve a delay.

Spanish Star Z-45, Z-62, Z-70 and Z-84 SMGs all use 18 flutes, except for one Z-70 variation which uses10. The CETME Model 58 rifle, designed by former Mauser engineers, used 16 flutes. Later still, CETME SPAM LMG in 5.56mm used 16 flutes, and the 1970s Spanish AMELI 5.56mm LMG was a scaled down MG-42 with a fluted chamber.

Germany’s Heckler & Koch (HK) developed the HK 91 from the Spanish CETME, itself an evolution of the late WWII Mauser Stg 45. After post-War France declined to go ahead with development of the Stg system, the ex-Mauser engineers moved to Spain to design the successful CETME. The Stg 45/CETME action did not actually lock. The system of semi-locked rollers remained locked under pressure and released as the pressure dropped. This worked well with the medium power German 8mm Kurz cartridge, but the full-power 7.62mm NATO was too powerful. The Spanish simply adopted a lower-powered version of the cartridge.

Germany, being a NATO member, was committed to the standard NATO cartridge, and German engineers were determined to make the roller-lock system work. They made a development deal with CETME and added chamber flutes. This made all the difference; the resulting HK91 rifle was adopted by Germany as the G3. The various HK91 rifles and the firm’s HK93 5.56mm NATO rifles use fluted chambers with 18 flutes, and the belt-fed HKs in 7.62mm NATO all use chamber flutes. CETMEs soon featured the flutes. The function of the flutes has been occasionally misinterpreted as a method of slowing the extraction similar to a chamber ring, but this was never the case.

The long case of the .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire is a challenge for auto-loaders to extract. The original AutoMag II made by Arcadia Machine and Tool (AMT) used chamber vents to overcome this. The reintroduced version from High-Standard does not.

Fluted Chambers for Handguns

HK applied fluted chambers to their handguns as well. The HK 4 in .380 issued to German police and Customs has chamber cuts designed to delay the action. The HK 4 in .22 also has four flutes, but they are meant to assist extraction.

Many roller-locked guns, whether fully locked by design or not, have a weakness known as “bolt-bounce.” If the rollers are not properly positioned at the instant of firing, the bolt can open prematurely with severe consequences. In the MG42, the bolt can close and the firing pin strikes the primer at the appropriate time, but if the inertia of the bolt slamming to battery results in the locking rollers momentarily “bouncing” back when a cartridge coincidentally hangs fire, the result can be catastrophic. The ill-timed delay in ignition can cause the cartridge to fire with the gun unlocked. This was cured by adding a device to the bolt which held the rollers outward to prevent any bounce. The same issue affected the Swiss SIG 510. In this case, the gun fires from a closed bolt, but here again the slamming of the bolt could cause it to bounce back and partially unlock. The Swiss chose to cure this by modifying the chamber. It incorporates flutes to float the cartridge case, but the chamber also has a step at the shoulder which prevents the case from fully entering the chamber until the closing bolt rams it in a fraction of an inch. This slows the final closing and keeps the bolt face from striking the back of the barrel hard enough to generate “bolt-bounce.”

The discontinued 9mm and .40 HK P7 and the P9S 9mm use flutes to assist extraction. The 9mm HK MP5 submachine gun uses16 flutes.

The German engineers who developed the late WWII MP45 migrated first to France and then to Spain to develop their semi-locked roller rifle. The Spanish CETME is shown.

The Kimball

A post-World War II American handgun took Mann’s design to the extreme. While Mann’s guns were small and elegant, the Kimball was pure Detroit. Born in the 1950s, it was big, brawny and loud. Made by J. Kimball Arms, it fired the .30 carbine cartridge. The carbine round may be considered sub-powered for a shoulder gun, but it is certainly at the top end of pistol ammunition.

The Kimball is a large gun, or was, as its career was short. It was an attractive gun, finely cause dangerous conditions, particularly when powerful cartridges are used.

The substantial recoil, large flash and enthusiastic operation made the Kimball a handful to shoot, but fear of mechanical failure doomed the enterprise. The slide relied on lugs at the rear of the frame to bring its rearward travel to a halt. Several examples showed evidence of being battered out of shape, and this led to fear of the lugs failing and letting the slide rocket back into the shooter’s face. There are no reports of this actually happening, but several reviews pointing out the perceived dangers helped bring the enterprise down in 1955. Only 238 were made, and it is a sought-after collectors’ gun today.

The Mauser Broomhandle was a popular gun in China. The Type 80 followed its concept and used a chamber delay as shown.

The AutoMag II

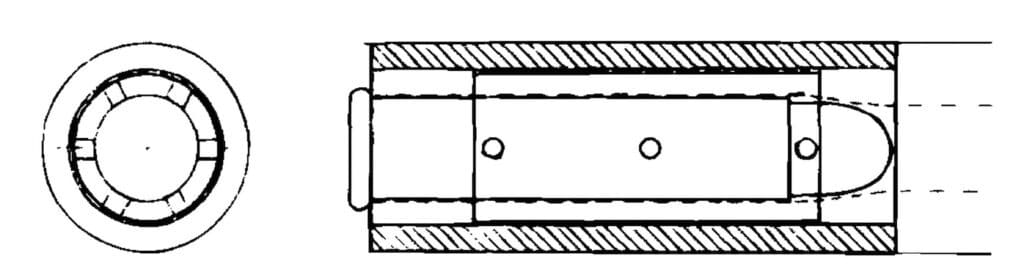

At first, the Winchester Magnum Rimfire cartridge, or WMR, was deemed too powerful for straight blowback. One of the first to challenge this limitation was the early AutoMag II designed by Harry Sanford and Larry Grossman and made by AMT (Arcadia Machine and Tool). The issue was not a premature exit of the case causing case failure but difficulty in extraction.

The AutoMag II used a unique system. The barrel outside the chamber is machined to thin it down, and 18 holes are drilled through into the chamber. The front six are located just ahead of the case mouth. A steel sleeve is welded over the machined and drilled outer chamber area. When the gun is fired, gas fills the small chamber created by the sleeve and bleeds back into the chamber through the 12 rear holes. The gas floats the case, reducing adhesion and allowing extraction. While it presents cleaning issues, the idea worked and could be made expensively.

Chinese Designers Take a Stab

Communist Chinese designers also resorted to fluted chambers. Their silenced Type 64SMG has three flutes at the front of the chamber. The Model 80 7.62mm full-auto pistol (a homage to the 1932 Mauser 712 broom-handle) has six flutes; the more conventional Type 64 in 7.62mm has four helical retarding grooves; and the Type 77 7.62mm has an annular groove near the back of the chamber to retard operation.

The AutoMag II fired the WMR .22 cartridge. Eighteen holes served to route gases to float the case and smooth extraction.

Grendel P30

The Grendel P30 was designed by George Kellgren and first marketed in 1990. The 30-round handgun fires the .22 WMR. Kellgren incorporated 16 chamber flutes to aid in functioning. Production ceased in 1994.

A range of .22 WMR cartridges suited to short barrels enabled Kellgren to refine the P30 design into the Kel-Tec PMR-30 without using a fluted chamber. When Hi-Standard re-introduced the AutoMag II, they were able to eliminate the holes in the chamber of the originals.

Today, the legacy of Mann’s handgun lives on in L.W. Seecamp Co. guns. Seecamp was founded by Ludwig Wilhelm Seecamp, a gunsmith in pre-WWII Germany and a survivor of service in the Waffen-SS on the Eastern Front. Seecamp came to America after the War and settled in Connecticut. He began making a simple concealable double-action in .25 ACP. He had doubtless seen the Mann guns in Germany and used the chamber-ring delay to develop .32 and .380 versions. Admirers called them the “Rolex” of small handguns and demand soon out-reached supply. After the elder Seecamp passed on, the company remained a family enterprise, run by his equally talented son, Lueder “Larry” W. Seecamp. Before Larry Seecamp passed on in 2018, he sold the company. The larger caliber guns are now made in Massachusetts, no longer back-ordered and still remarkable for their quality, small size and concealability.

Certainly the fluted chamber fills a narrow area of need, but shooters will be puzzling over oddly patterned brass on the ranges for many years to come.

• • •

My thanks to James Samalea, Carol Mintoff, Larry Albright and Mike Strannahan, Albright’s Gun Shop, Benedikt Rieger, Chuck Hawks, Finn Nielsen, Joseph “Jay” Bauser, Lisa Weder, Movie Armaments Group, Peter Dannecker, Sprague’s Sports, R. Blake Stevens, Rock Island Auctions, Noel Incavo, Midwest Sporting Goods, Shakeena Hearn, Adam Bucci, Rachel Hoefing, Ian Ballard at Glossover.co.uk, Stefan Klein, Wiley Clapp, Vaclav “Jack” Krcma, Journal of Forensic Science.

Terry Edwards has done numerous articles for Soldier of Fortune, Small Arms Review and Small Arms Defense Journal. His books are available on Kindle.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V23N9 (Nov 2019) |