It might seem strange that a series of articles about such a quintessentially patriotic American should be written by a Canadian, and there are two points I would like to make in mitigation.

First, I well remember the thrill of excitement I felt when I first discovered the series of paperbacks published in 1958 by the U.S. Army Ordnance School at Aberdeen Proving Ground. The Preface to Submachine Guns Volume I reads as follows: This text has been prepared with a twofold purpose in mind. It is to serve as a historical document and as a reference for use at the U.S. Army Ordnance School and in the field. It was compiled with the advice and assistance of Mr. G. B. Jarrett, Chief of the Ordnance Museum, Aberdeen Proving Ground.

As a young man in an era when an early edition of Small Arms of the World was just about the height of specialization in the field of arms literature, I knew immediately that this was a document of great value. Opening the yellow-covered Volume I to the Table of Contents, I had to read no farther than “Section I: German Special Rifles” to know I had to have this book.

Colonel Jarrett, his work and the publications with which he was associated have always occupied an important niche for me, and although I never met him, I have long considered him a mentor in my working life as a writer, editor and publisher. Therefore, when I heard from Dan Shea that some research material about Colonel Jarrett had come to light, I asked to be allowed to write this series of articles.

Second, as will immediately become apparent below, I have done very little of the actual writing as others far better qualified than I – mostly friends and military colleagues who knew, worked with and admired Colonel Jarrett – have already done it, and it has simply been my enviable task to put their material together. In this regard I must record a note of heartfelt thanks: first to James Alley Jr., Ph.D., who among his many fine tomes and folios has preserved a treasure-trove of Jarrett material, which he in turn acquired from another writer, editor and long-time Jarrett friend, the late Charles E. Yust. Second, to Thomas B. Nelson, who worked in Ordnance Technical Intelligence while in the service and regards Col. Jarrett as his mentor, and who has supplied some very interesting material from his personal collection. This accumulation of original documents from various sources, some written by Jarrett himself, has kindly been made available to me, and my main contribution has been to chart a circuitous, chronological meander through these yellowing papers to form the body of what follows.

Introduction

The tone, one of respect and admiration for Colonel Jarrett’s accomplishments, tempered by the veiled acknowledgement that he was not always the recipient of everyone’s wholehearted support, is set right off the bat by the following introduction to an article in the Ordnance Journal by Robert J. Icks, a fellow retired Ordnance colonel, which was published shortly before Colonel Jarrett’s death in 1974: There probably is not a single individual, military or civilian, who is interested in matters concerning guns, ammunition and other items of ordnance equipment or a single military or historical museum curator who does not know the name of Colonel G. B. Jarrett… he is representative of those unassuming but dynamic citizen soldiers whose attainments represent a degree of professionalism not exceeded and seldom equalled by professional soldiers in the same fields.

Early Days – Accumulating “Burling’s Junk”

According to his obituary, published in the Harford Democrat on July 3, 1974, George Burling Jarrett was born in Haddonfield, New Jersey, on October 14, 1901, the son of Joseph Roberts and Laura Burling Jarrett.

Col. Icks’s article, begun above, continues as follows: As a boy, young Burling grew up among Civil War guns and trophies belonging to his grandfather, an officer in the Union army. His father was an understanding man who permitted him to find out for himself how everything worked.

A more colorful embellishment of the exploits of the young Jarrett (who incidentally was known to his friends and family as “Burling” rather than “George”), is found in an initial excerpt from a lengthy and very well-researched article written by an Arch Whitehouse titled The Junkman Who Stopped Rommel, published in the December, 1957 issue of Cavalier magazine: For George (the collector’s mania) had burst into full bloom one Fourth of July when he was five years old. To celebrate the holiday properly, his grandfather had fetched out his Civil War rifle, choked with rust and cobwebs, and fired a blast that nearly rattled the old gentleman apart. Not to be outdone, George’s father brought out his Colt .31 cap-and-ball revolver and nearly blew off his hand when he used more powder than caution. George was delighted. These were just the kind of lethal toys to delight his mind, and when he begged for a chance to restore the relics to perfect working condition, the senior Jarretts raised no objection. They thought the weapons were beyond repair, and not until they caught their five-year-old heir gunning for woodchucks with both toys in prime condition and loaded for bear did they lay down the law. By that time it was too late. George had the bug.

Except for mathematics and military history, school brushed lightly over George. He lived mainly for his collection, using such funds as other kids squandered on jaw-breakers and all-day suckers for adding to his collection of arrow heads, bullets and rusty cannonballs from Civil War battlefields.

An article published in Popular Science in May, 1944 continues the story and immediately dispels any suspicions that Jarrett’s collecting mania was underwritten by a bottomless parental purse: The quiet old Quaker town of Haddonfield, N.J. was inclined to look askance at young Jarrett’s passion for the instruments of death. It was not long before his trophies filled every available inch on the walls of the young collector’s bedroom. But the older Jarretts took alarm when “Burling’s junk” filled the attic and began to spill over into the basement.

The Jarretts were not wealthy, and they were of no mind to advance hard-earned cash for such a useless-seeming enterprise as young Burling’s. But he easily hurdled that obstacle. Summers he worked as a helper on a delivery truck. So single-purposed was he that he never learned to smoke cigarettes. Every spare bit of cash was saved for investment in the growing collection of “Burling’s junk.”

The First of Many World War Acquisitions

An initial excerpt from the draft of an article written and typed out by Jarrett himself, dated May, 1971, provides an early inkling of the purposeful nature of his seemingly random collecting interests:

The effort to gather curios of a military nature can require fascinating and exhaustive study as well as gradually to acquire a collection worthy of note. While the art itself has personal rewards for the individual there are times when such an endeavor might be of great technical value to one’s country.

For many years I have been interested and fascinated by weaponry, starting with the story of the Civil War. From childhood, when my grandfather’s relics from that war hung on our staircase wall, they had intrigued me. Gradually as I grew older, I added other pieces of that era and the whole war became apparent to me.

In the 1914-15 period I experienced the details of the new war then at hand, and with avid interest I followed all the printed news and photos then available. Early in the war a young man from my home town of Haddonfield, New Jersey left for France and to serve as an American ambulance driver. He wrote to me several times and in 1915 sent me two buttons, one from a French and the other from a German uniform. That started me on World War I collecting.

Coming of Age During the World War

The December, 1957 Cavalier article continues the saga of Jarrett’s young manhood as follows: At 16, with an after-school job to augment his income, he moved to bigger things by haunting John Kreider’s old gun shop at Second and Walnut in Philadelphia. His first purchase was a .69 caliber musket used at the Battle of Bull Run. The price was enough to exhaust his income for a month, but not his collector’s mania. As his gaze rove through the shop, he saw item after item he simply had to have, and the thought that some other customer might buy them first was too antagonizing to contemplate.

“Save them for me,” he pleaded. “I’ll be back.” And he always was, though at one time the amount of stuff marked “Hold for Jarrett” threatened to devastate his salary for the rest of his foreseeable career.

World War I caught Jarrett short by a couple of years, a frustrating circumstance he partially relieved by commissioning all his older friends to bring back all the souvenirs they could get their hands on. Fortunately, by 1918 he was big enough, if not old enough, to get a job with the New York Shipbuilding Co. By spending his days at the yards, and his evenings at nearby Camp Dix, he was able to buy up hundreds of trophies brought back from the front by returning soldiers that included machine guns, belts of cartridges, Mauser rifles, helmets, trench mortars, Mills bombs.

An initial excerpt from an article in the July, 1937 issue of the periodical Flying Aces, written by “Lt. G. B. Jarrett, Curator and Owner of the Jarrett Museum of World War History”, reads as follows: Two small military buttons picked up back in the stormy days of 1915 started me off in the World War relic game. To the buttons, I gradually added other odd pieces, and it wasn’t long before my bedroom was resembling Ye Olde Curiosity Shoppe.

Col. Icks’s article continues to describe how Jarrett ever more purposefully continued to amass World War collectibles: During World War I, older friends sent him buttons, badges and shell fuses. The fuses naturally were disassembled, examined, the component parts sketched and instructions recorded on the sequence of reassembly. He finished prep school in 1920 and during summer vacations worked at the New York Shipbuilding Company yards because they were near Camp Dix, New Jersey, and Camp Dix had war curios for sale after World War I.

Jarrett Visits the Battlefields of Europe

Jarrett’s own July, 1937 article in Flying Aces continues as follows: The summer of 1922 found me wandering with a watchful eye through the battlefields of the Western front. In order to get better acquainted with the shell-hammered sectors and to come closer to their spirit, I rented a bicycle, and pedaled about the country. My entire equipment – mainly a toilet kit and a blanket – was carried on the “wheel”. I often spent nights with peasants of the section in crude shacks they had built from leftover military supplies – sheet iron, ammunition boxes, and the like. And curios of every kind were mine for the taking, as they lay in indescribable confusion on the deserted battlefields. In the early fall of the year of my battlefield tour, I returned to America and to school.

Col. Icks adds his own comment on Jarrett’s 1922 trip to the European battlefields: Since this was only four years after the war was over, much of the wreckage of war and the appearance of the terrain was unchanged. Jarrett collected guns, shells, ammunition, maps, uniforms and a host of other materials and found means to get them shipped home.

The well-done Cavalier article embellishes this part of the Jarrett story, beginning in 1918, the year the World War ended, as follows: All he could think about for the next four years was that war-torn Europe was one vast museum of military equipment, all falling apart for lack of a Jarrett to give it protective ownership and in 1922 he wangled a job in Antwerp with a New York importing firm. It is doubtful that he earned his salary. Most of the time he was off on a bicycle touring the battlefields and keeping the shipping companies happy with crates full of his acquisitions. As an example of his methods, at the famous Ypres battlefield he roomed for a week with two elderly sisters who were eking out a gentle living making lace. “That’s nonsense,” he told them. “Why don’t you just collect a few bombs and things like that for me? I’ll buy all you can send me.”

For eight years the lavender-and-lace Haellert sisters made an incongruous team as they minced around the shell-pocked battlefields, but they shipped Jarrett thousands of items, and wealthy spinsters they were when they retired. Elsewhere Jarrett had a score of other “agents”, but none to compare with the frail lace makers. “To see them disarm a mine,” he said admiringly, “why, you’d think it was as safe as threading a needle. For them I guess it was.”

Jarrett’s 1970 article contains the following tongue-in-cheek recollection: I had all this displayed in my home bedroom and the cellar. When I moved to Atlantic City (in 1930) it is possible that my mother welcomed my exit.

Jarrett’s July, 1937 Flying Aces article continues: I took my first definite inventory in 1926, (and) I had more than two thousand pieces! Most of these later acquisitions I gained through barter.

Col. Icks confirms this, as follows: During this period, many Army and Navy surplus stores came into existence. (Jarrett) became well acquainted with these merchants between 1926 and 1928 and not only purchased many items but in return for identifying items, he even worked out trades.

Jarrett himself continues the story, from his July, 1937 Flying Aces article: In 1928 I took my collection on tour through many of the eastern states on behalf of some of the veterans’ organizations. Returning, and adding accumulated items to the whole, I found that the collection weighed more than four tons.

By now, I realized that my two-button collection was well out of the “just-a-hobby” class, and was, in fact, a small museum.

Already it was about driving me out of the house – for bedroom, third story, cellar and “all way stations” were full to overflowing with these valuable, often cumbersome, War trophies.

The Jarrett Collection Moves to the Steel Pier in Atlantic City

Arch Whitehouse’s excellent article in the December, 1957 issue of Cavalier picks up the thread as follows: By 1930 Jarrett was back in the United States, the proud owner of more workable items than could be found in any other military collection in the world. Other ordnance experts might know more about their highly select fields, but as the man who had restored Russian, German, French, Italian, British and American equipment to working order, he knew more about ordnance in general than did all the experts of Krupp, Woolwich Arsenal, and the Aberdeen Proving Ground combined.

His timing was perfect, and a fortunate thing that was for his exhausted bank account. Ten years earlier the veterans of World War I wouldn’t have paid a nickel to tour a military museum, and the major part of them had sworn, in fact, never to look at a gun again. But by 1930 nostalgia had set in, and with wives and children to impress, they came in increasing numbers.

The original typescript Foreword to Jarrett’s memoir West of Alamein, published in 1971, begins as follows: From 1915 to 1930 I had managed to gather a large curio collection and to keep it in an ordinary dwelling such as my home in Haddonfield, N.J. In 1930 I had at least 3,000 items, which weighed between three and four tons.

I met a grand and thoughtful man in Mr. Frank Gravatt who at the time operated the world famous Steel Pier at Atlantic City, N.J. To him I said I had the Museum with no roof over it, and that he had the roof and no Museum to put in it. So we joined hands and I moved onto the Pier lock, stock and barrel in the spring of 1930.

The Steel Pier provided me with an annual cash turnover, and for once I was funded to acquire spectacular and heavy items and move them onto the Pier.

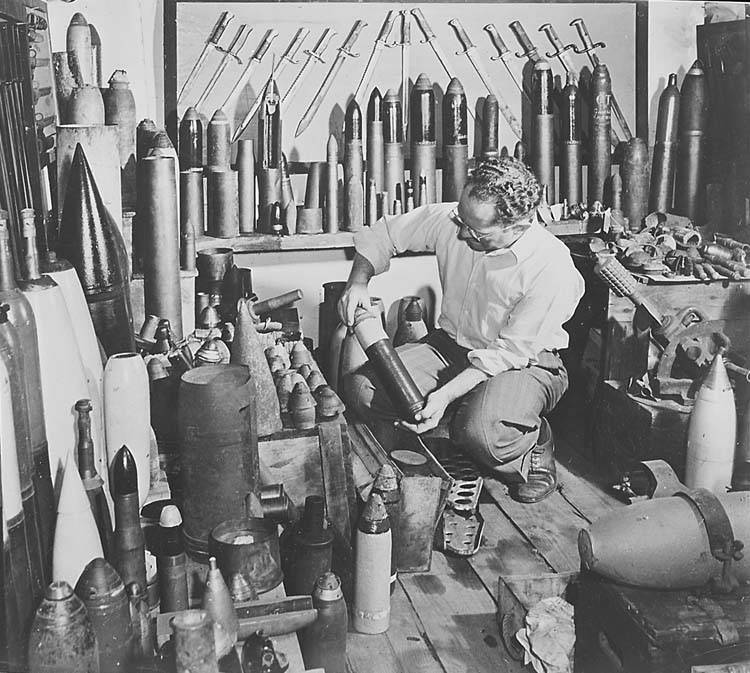

Col. Icks augments Jarrett’s recollection, as follows: By 1930, Jarrett had become completely familiar with all kinds of ordnance used by both sides during World War I and had collected more war material than most museums. He contracted with the Pier authorities to set up on the Steel Pier at Atlantic City “The Jarrett Museum of World War History”. The collection began with some 3 1/2 tons of curios.

A typescript draft for a later article by Jarrett dated May, 1970 confirms and consolidates the above regarding the important milestone of establishing the Steel Pier Museum as follows: During the 30s I joined hands with a Mr. Frank Gravatt who then operated the Steel Pier, an amusement center in Atlantic City, New Jersey and known the world over. He had several sections of the Pier which had space adaptable to static displays of an educational nature. He gave me a home for my Museum collections, which at that time numbered more than 3,000 pieces and weighed over 3 tons. I displayed the Museum on the Pier from 1930 to 1939.

In the typescript Foreword to West of Alamein, Jarrett mentions another event from 1930 that had great personal importance: I almost forgot I got married on the strength of my move onto the Pier, and (our marriage) has held together despite the collection of curios and all the ramifications that it can provide.

“The Jarrett Museum of World War History”

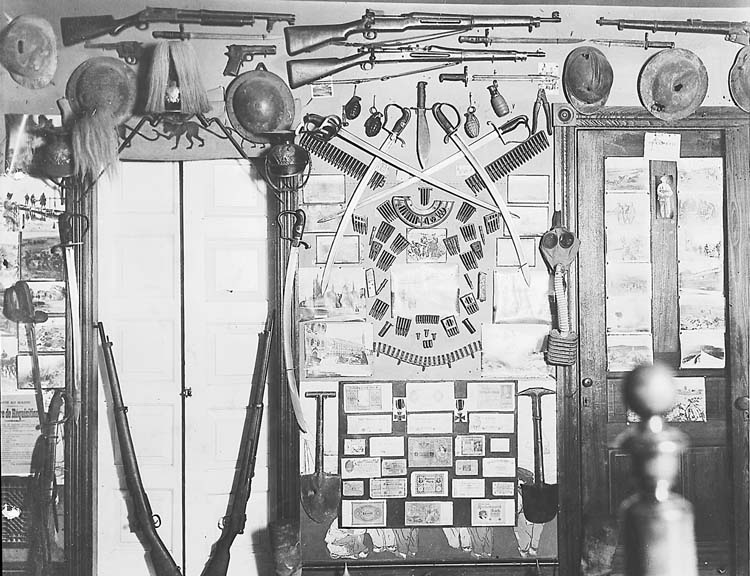

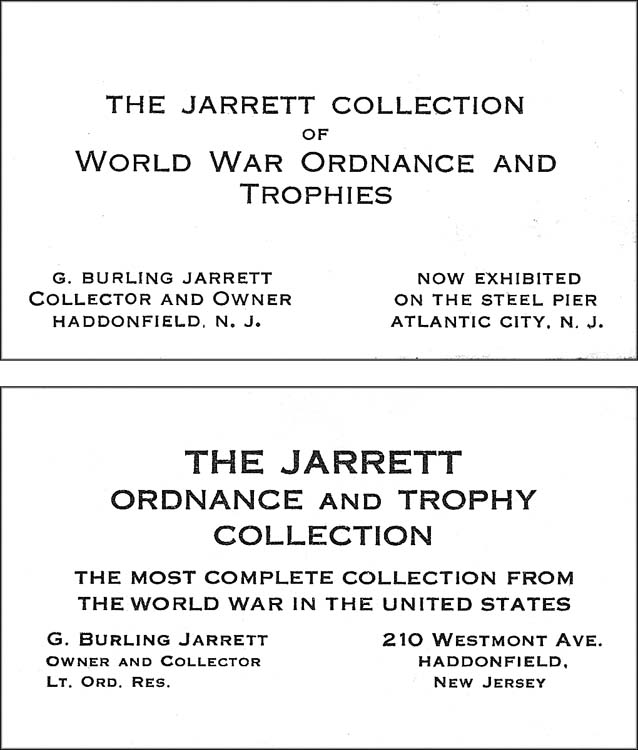

Several flyers and brochures among the documents collected by Charles Yust were handouts and catalogs procured over the years during visits to “The Jarrett Museum of World War History, Steel Pier, Atlantic City, N.J.” One such is a double-sided orange card and the reverse reads as follows: This Museum is the effort of G. Burling Jarrett, O.R.C., who has spent more than fifteen years assembling it. The collection from the Great War numbers over 6,300 pieces with a total weight of over sixteen tons.

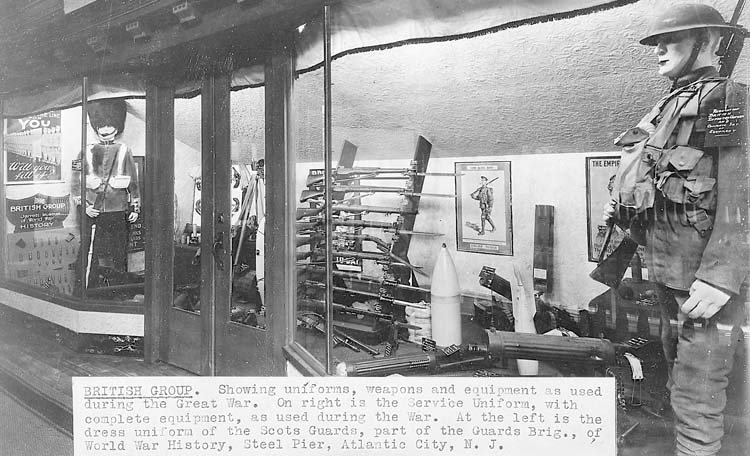

The Museum is divided into nationality groups and specimens are exhibited from all branches of the various services. In this exhibit are several airplanes, most prominent of which are a Sopwith Camel and a Fokker triplane.

Numerous artillery and heavy ordnance pieces, and one of the original 1914 Paris taxicabs are also to be seen.

In addition there is a remarkable assortment of small arms, uniforms on figures, equipment, ammunition and hundreds of wartime authentic photos.

A number of scenes have been constructed to enable one to visualize wartime trench life and to show certain relics in an historically true setting.

It is without a question a Historical Museum and not a collection of curios that incite and recall old hatreds. All ex-servicemen as well as others should see this display. The co-operation of the Steel Pier has made this museum possible and placed it before the public.

Running Out of Room Again – Moving to the Farm

As the typescript draft of Jarrett’s May, 1970 article continues: Since I then began to get financial help by way of the contract with the Pier, I sought some really spectacular pieces and at once began to display aircraft, artillery and automotive pieces with a WWI record. The Pier as early as 1935 could not allow me more space and I had moved a vast amount of my heavy items to my farther-in-law’s farm near Moorestown, New Jersey. During those last years of the 30s I displayed the Museum both at the farm and on the Pier. More than 9,000,000 people visited the Museum during that time.

Col. Icks confirms the need for more space: The space on the Steel Pier was insufficient to house everything he was collecting, so his father-in-law gave him space for storage at his large farm at Moorestown, New Jersey. Here, Jarrett restored his planes to working order. Jarrett not only collected planes during this period, but also larger pieces of ordnance including heavy artillery pieces, all of which were stored at the farm. The Ordnance Department gave him a 6-ton tank which, according to regulations, had been made unserviceable but, together with his brother-in-law, he put it back in running order.

“Reviving the World War in New Jersey”

Along with the freedom and scope of outdoor display space came the happy thought of inviting various groups and interested parties to come and inspect the collection and perhaps witness some actual maneuvers. The first of several annual “field days” was held in October, 1934.

A foldout flyer from the “Research and Curio Center, Moorestown, N.J.” records one of Jarrett’s famous purchases: an “original German Pfalz D12 (biplane), imported to Hollywood for Warner Brothers Dawn Patrol in 1928 and seen since in many other movies; brought from Hollywood to the Museum in 1937 and restored to wartime appearance and condition.”

This story is confirmed by a faded Bill of Lading from the Shepard Steamship Co. of Los Angeles, dated October 15, 1937, which documents the shipment of the Pfalz biplane, described pessimistically by the shipper as “1 uncrated old 2nd-hand German airplane in one bundle – wings collapsed to side and roped. Fabric torn. Tires flat. On Deck – Owner’s risk. Vessel not responsible for damage.” The freight charge was $79.75.

Despite the obvious risks involved, notes pencilled in Jarrett’s handwriting confirm that the aircraft “Came thru OK. Arrived at Museum Nov. 6, 1937.”

The 1937 Field Day at “Little Aberdeen”

A now-crumbling page torn from the June, 1940 issue of a large-format colored newsmagazine records that “Lieutenant G. Burling Jarrett, (by then an) instructor at the Ordnance School Aberdeen, recently conducted his class in south Jersey, where he has a collection of arms from the World War. Here he staged a small war of his own by showing how the Germans and Allies operated about 25 years ago.

“One of the spectacular demonstrations presented by Lieutenant Jarrett was one showing the effects of land mines on an American light tank. The tank’s ability to drive over barriers was also demonstrated.”

Lieutenant Jarrett wrote an article titled Little Aberdeen, describing his 1937 field day on the farm which was published in the October, 1937 issue of Army Ordnance, excerpted as follows: The fourth annual field day of the Jarrett Museum of World War History was held May 8, 1937. This year the faculty of the Bordentown Military Institute of Bordentown, N.J. joined the writer along with over 700 spectators to witness the exhibition, which was held on the Workman Dairy Farm, Moorestown, N.J.

As a collector of curios, I long had toyed with the dream of some day having both the material and a suitable space to imitate the Ordnance shows held at Aberdeen Proving Ground, if only on a tiny scale.

Regarding this museum, let me say that a “den” collection is one thing, but when one starts shipping home artillery, warplanes, automotive pieces, etc., it is another. A serious housing problem soon presents itself. For years I have been cramped for space, and only in the past twelve months have I moved the entire museum – little by little – to one address – the 88-acre farm at Moorestown where the museum section is known as Artillery Park. It takes two acres to store the museum and five to display it! Realistic settings are easily obtained, and the best feature of all is that maneuvers can be held and certain types of firings or demonstrations attempted with safety.

Recalling Some Famous Donations

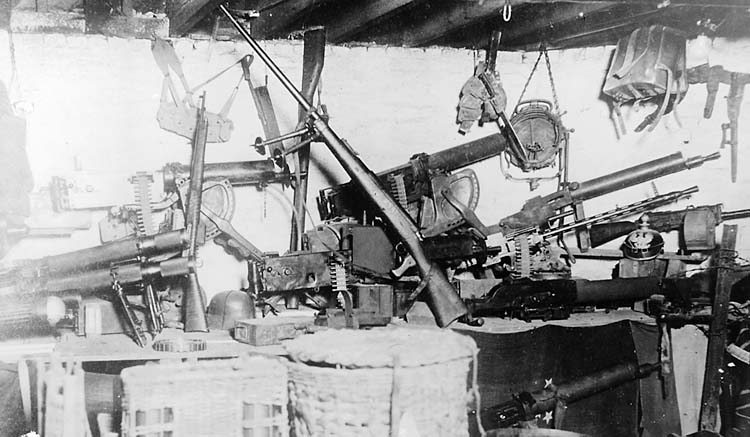

Jarrett’s 1940 Little Aberdeen article continues: The museum has, after some twenty-two years of collecting, reached more or less elaborate proportions. The Italian Government, during the past two years, has donated some very valuable sets of equipment, together with a complete library of twenty-one volumes on its activities during the World War, an album of photographs, and a hand-carved desk. The British War Office furnished several valued books for the research library, which has reached large proportions of late. The Crown Prince of Germany presented one of his caps worn at Verdun, and Col. Armand Pinsard of the French Flying Corps presented a cap that he used during the war.

The machine gun section of the museum is worth passing mention, as it contains sixty-five specimens. I have, perhaps, been especially interested in these guns, and a discussion of them is a story all by itself. Light and heavy ground types, tank, aircraft and antiaircraft types form the group, with but two or three patterns missing from all such designs made up to 1919.

Paramount Films the Last Show at “Little Aberdeen”

As World War II loomed ever closer, Jarrett’s original Foreword to West of Alamein records the last field day at “Little Aberdeen” and the closure of both the farm and Steel Pier exhibits: In 1939 Paramount Studios, who produced each month a short film called “Unusual Occupations”, asked me to run a show for them that they might film it. This I worked on and in July of ’39 they came and filmed it. This film was shown all over the USA and also abroad, I got hundreds of letters. In August I ran one of my regular “Little Aberdeen” shows since I had arranged all the pieces for Paramount. This was as the war clouds were beginning to gather over Europe. This was my last show, and in the fall I closed down operations on the Steel Pier and at the farm.

Col. Icks describes the collection as it then existed on the Steel Pier:i By 1939 (the Steel Pier collection) had grown to 75 tons, and over nine million persons had seen the exhibit…

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V14N11 (August 2011) |