By Dan Shea

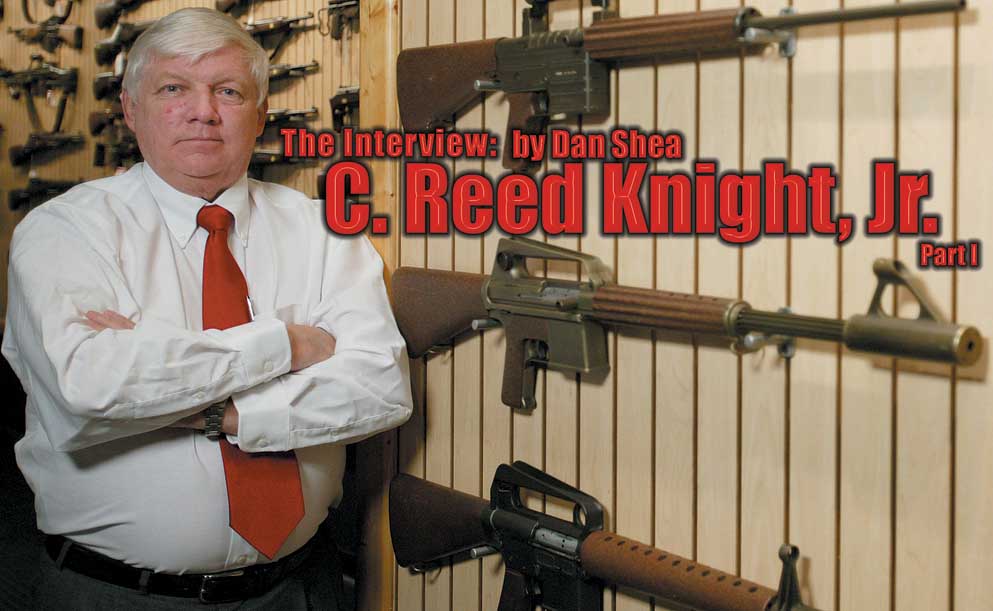

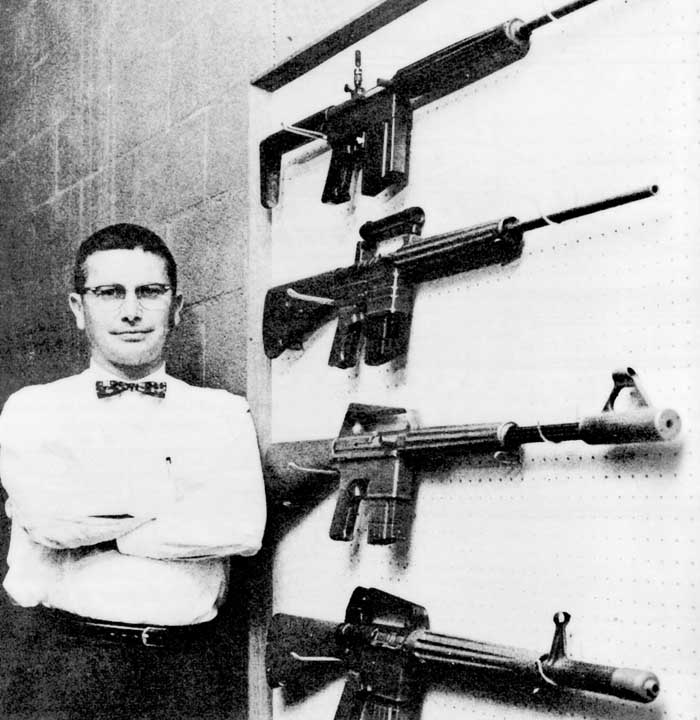

C. Reed Knight, Jr. was born on 22 August, 1945, in Woodbridge, New Jersey. His family moved to Florida before he was a month old allowing him to claim he didn’t have time to be corrupted into a Northerner. His father, C. Reed Knight, Sr. was in the US Army Air Corps at the time flying B-25 bombers stateside as he had finished his pilot training in 1945 just as WWII ended. Reed is married to his high school sweetheart Jan, whom he married in 1967, and they have four children; oldest son Trey, middle son Jacob, youngest son Will, and daughter Sarah, ranging in age from 21 to 38. Reed attended a number of colleges including Florida Southern, Bavard Engineering College in Melbourne, Florida, and Indian River Junior College in Fort Pierce, Florida. Reed served six years in the National Guard starting in 1965. Reed’s companies are some of the amazing success stories of the small arms world, having grown to the point of employing over 300 people today in the manufacture of weapon systems and accessories that Reed has invented and put into production. The list includes the SR-25 rifle he designed with his late partner Eugene Stoner, as well as the Rail Interface System on most current small arms, and many suppressor designs and other firearms. The Knight Collection is one of the most important small arms collections in the world, and Reed’s devotion to the study of small arms has helped the community in too many ways to count. Reed is a tough businessman with a clear view of what he wants to accomplish, and very little patience with anything that interferes with making a proper, top of the line product.

SAR: Where do you think your interest in mechanical things came from?

Knight: I guess from the very beginning my earliest memories were of taking things apart. I like to see how things work. Maybe the side of my brain that’s mechanical overrides the side of my brain that does the reading and the spelling and the other side. I’ve always been able to see things in multiple dimensions and understand them in a very complicated way mechanically. My dad is like that, also. It’s a form of dyslexia, and he basically could not read or write. I have a very tough time reading and writing, too. When I was young, my dad told me, “Son, you can make a living at 40 hours a week, and you can do a little bit better at 50 hours a week, and you probably can do okay at 60 hours a week, but you’re so damn stupid, you’re gonna have to work about 80 hours a week. I suggest you go find yourself a job that you like doing because you’re gonna be spending a lot of time at it.” {Laughter} He was pretty close to on-target with me. I told my dad at the time that I liked guns, and he said, “Well, I guess you better find a way to make a living playing with guns.” I’m one of the very fortunate few people that have managed to make a living out of my hobby.

SAR: Weren’t you racing cars before the firearms?

Knight: Actually, the interests were concurrent. I built cars in high school. When everybody else would go out dating and going to parties, my future wife and I would go over to my garage at my grandfather’s house where I had Model A’s and different types of cars that I was working on. We used to make dune buggies and head down to the beach and go hunt turtles on the east coast of Florida. Model As were cheap, very lightweight, and we’d put big tires on them, strip them down to where they’d weigh almost nothing, and then drive right on the beach. We would run up and down the beach and that was our weekend fun: running from inlet to inlet on the east coast of Florida. We weren’t interested in making the cars original; we were making them into what we wanted out of them. I had a brand new ’63 Chevrolet Super Sport, less than three months old, and my mom and dad went out of town for the weekend. When they came back, I’d pulled the engine and transmission out of that to put it in my ’55 Chevy, and I had lightened it up and put a blower on it, put the big slicks on the back, and I never will forget the look on my mom’s face when she saw that I had taken this brand new car and tore it all up into my hot rod. I had to put the motor back in my street car, under duress. My dad and I put a motor together in my second floor bedroom for the hot rod. We were carrying it down the steps, and he was in front and I was in the back, and he tripped, and the motor cart-wheeled down the staircase and landed upside-down in the middle of my mother’s living room and the oil ran out and ruined her carpet. She was pretty upset when she saw it and asked, “Why in the world did you put this motor together in your bedroom?” I said, “Well, that was just the cleanest place that I could think of to put this motor together.” She got a brand new carpet out of that deal. She caught me at college where I had converted my kitchen sink into a parts washer and the rest of the kitchen into an assembly area. It’s “guy logic,” all those things were a natural for working on engines.

SAR: Did you have access to a machine shop?

Knight: My family has been in the citrus business forever, so we had our place where we worked on all of our tractors and I had a welding shop and a machine shop; everything that you would need to work on tractors. It was basically a mechanical heaven. I would work at my dad’s shop during the summers taking tractors apart, fixing them, putting them back together and working on the heavy machinery. I loved it. My dad kept having clutches slip on some of his tractors that were using a “tree hoe.” I knew about a special clutch used on dragsters, so I sent one of the clutches in and had them build the dragster clutch plate package to fit on my dad’s Massey Ferguson tractor. It was so successful that Massey Ferguson came over and used the idea, and every tractor since then has that same clutch pack that I had altered. I guess that was my first invention that got adopted. I was about 16 years old when the Massey Ferguson deal happened. I got a Farmall Cub tractor for my 9th birthday, which was electric start but I had to hand crank it like a Model A, and I learned to work on that real fast. I mowed yards with it. My dad had a team of mechanics that used to teach me about engines and I would repair the tractors and the semi trucks that we hauled the fruit with. It was a lot of fun. I rebuilt a lot of transmissions and engines. Between 1965 and 1968, we road-raced Camaros at the “Baby” Grand Am – the pre-runner to the Bush races. Camaros, Firebirds, Mustangs and the little Ford Cougars, they would all race the day before the Grand Am, before Richard Petty, A.J. Foyt, and all those guys. I think it was year ’67 we ended up in the NASCAR points. We were seventh in the nation with just a three-man team. We had a driver called Billy Yuma, and I was the mechanic and about everything else. I never will forget sitting on the pit box and we had built this device that shook the rubber off the radiator because the radiator kept getting clogged up on the car, and Richard Petty walked by and saw it. He said, “Well, son, I really like that idea. I’m gonna do that.” He was the king back then, and that was thrilling. I did enough driving to scare myself half to death. What I really liked was drag racing, and I set four national records way back in the old days. I had an A Comp dragster with a 396 Chevy in it, and I had a B dragster back when you could do it economically. My Mom didn’t catch me this time, but the motor came out of my ’65 Corvette. [laughter] I guess I didn’t learn my lesson in ’63. Of course, my mom tells the story now as if it was funny but she didn’t act that way back then.

SAR: Reed, you talk about driving around off-road, plinking and shooting. What was your first firearm that you remember?

Knight: I started with bow and arrow in the 1950s. I was very competitive, and that went from archery to firearms to cars. I used to shoot .22s all the time. Being in the citrus grove business, we’d hunt rabbits, squirrels and varmints. I had a Winchester gallery pump gun. It was just part of every day life, plinking and hunting. My dad had an interest in arms and armor, and he took me to Europe where we bought a lot of antique guns and armor. The Customs guys thought we were in the antique business because of the flint locks and cap and ball guns. My dad enjoyed the history of firearms: he was a collector extraordinaire. He collected tools, coins; he collected all kinds of things. I grew up in an environment where people had respect for the past, and the details and the discipline of collecting. My dad would bring home bags of quarters, and I’d sit down watching TV with a bag of quarters and going through separating them. First, pulling all the silver quarters out, and second filling in all the quarters in the books. Of course all the books having all the different rare quarters and filling them all through was exciting. In the ’40s and ’50s, that was real common. On firearms, I did some hunting, but not a lot other than around the groves. In my first year of college I was on the ROTC rifle team where we used .22 caliber Remington 52s. I was on the rifle team freshman year, and then I started shooting what’s called PPC, and that’s police combat shooting with revolvers. I was a reserve police officer with the City of Vero Beach in 1969-70 or so.

SAR: Had you seen machine guns at that point?

Knight: I had seen some, played with them, and when ’68 came along with the Gun Control Act and the Amnesty, you know, everybody was so skeptical about the registration process, that I didn’t get involved. There were plenty of guys with machine guns, and they’d go out and shoot them at ranges, and before 1968 if you made the gun where it would not shoot automatic, then it was considered not to need registration. When the law changed in ’68, it became “Once a machine gun, always a machine gun.” That changed the whole thing for everyone I knew. I didn’t have anything to register, so in 1968 I didn’t make any. Sort of the opposite. Everyone was pretty cynical that the government was going to come take the guns away once they got them all registered. Most of the people that I ran with back then, because I was shooting pistols and stuff, were either police officers or friends of police officers. When the law changed, they took their guns and either gave them up or gave them to somebody else, or actually turned them in to the department, and let the department do the paperwork. People generally thought there would be a confiscation. They sure didn’t know they were going to be worth $10,000 or $20,000 apiece. Remember we’re talking about machine guns that people had bought very cheaply. They were buying Thompsons from InterArms for $125. The machine guns weren’t worth much even after the Amnesty for a very long time.

SAR: Were you doing any gunsmithing?

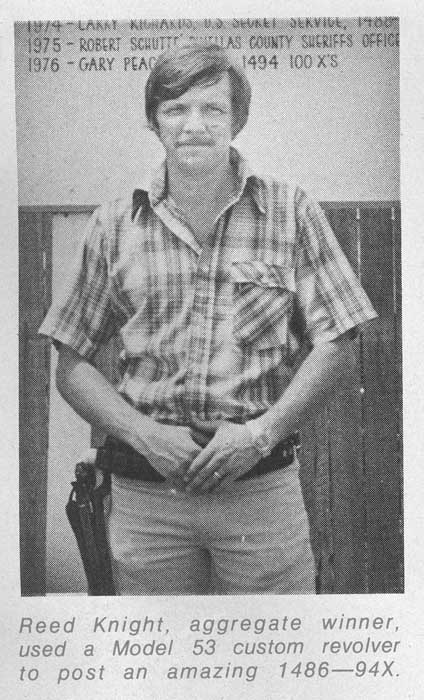

Knight: Yes. I was shooting about 50,000 rounds a year of .38 special ammunition and I had to reload that because it was so expensive. I was reloading at night, and shooting during the weekends. I had my own range and my own targets as well as turning targets. I had one of the best ranges set up. During the winter, all the shooting teams from the United States Secret Service would come down and practice at my home in Florida. It was cold up north and if they could get another couple months of practicing, they could get a head start on the year. Some of the early matches were held in Florida. The very first regional match was held in Pompano, Florida. I would travel with them to and from matches, pretty much all over the country, shooting. I enjoyed that, and I worked on the guns. I built combat guns and built the sights on them, and built the big, heavy bull barrels, and worked on the actions, put ball bearings in. I had a milling machine and a lathe, and a couple of real sharp files. I learned how to thread barrels, how to set head space and polish parts. One of the things I did was I built an adjustable trigger stop that in the combat you would use a two-stage trigger pull, rather than cocking the hammer. The amount of movement on the trigger would rotate the cylinder and cock the hammer and get everything locked up, and then you’d break the hammer, and it was very accurate. Back in those days I was building guns and shooting with wadcutter ammo, and we were shooting one-inch groups at 50 yards. I liked Smith & Wesson’s.

SAR: Were you collecting Smiths?

Knight: When ’68 came along with the Gun Control Act, I started very intently collecting Smith & Wesson’s. I didn’t have an FFL yet. I was collecting to try and get one of each and condition wasn’t too important at that time. They didn’t have to be new in the box. The hard guns to get were the snub noses. You wouldn’t think it today, but back then the little J frames were very hard to get because they were concealable and everyone thought the government was after them. Smith and Wesson wasn’t building enough of them for the customer base. The basic law change in 1968 was in fact going after concealable handguns and stopping interstate commerce in so-called “Saturday Night Specials.” Getting all the different models with all the alloy frames, the different concealed hammers and features sure was interesting to me. We were all into revolvers. Remember, not only myself, but there were no police officers that even thought about carrying automatics. They were not considered to be a weapon of choice for a police officer.

SAR: When was the first time you saw a sound suppressor, a silencer for a firearm?

Knight: I’m sure I saw some in the 60’s, but they didn’t really interest me then. I got into machine guns first. I had a very early semiautomatic AR-15; a three-digit serial number Colt Model SP-1. I was at a gun show and a friend of mine came over and gave me a barrel bag. I unzipped it and there was this barrel in it, it was obviously a heavy barrel, it was a quick change barrel, and I had no idea what that barrel fit. It had a barrel extension that looked like the AR-15. I started doing research. I found out that this guy Gene Stoner had invented a gun that was called a Stoner 63. I then found out that he was the same guy that invented the AR-15 which became our US M16. I read some of the books about the subject and I started thinking about if I could ever find one of these Stoner 63s. Roger Cox from Law Enforcement Ordnance Corporation advertised a Stoner 63 and in 1974, for $1,700, I bought my first Stoner 63. It was in the rifle configuration. Now I had the machine gun barrel and a rifle, and I was off on a quest.

SAR: A Stoner 63 couldn’t be your first machine gun… that’s just not right. {Laughter}

Knight: You’re correct. The very first machine gun I bought was a Military Armament Corporation MAC 10, and I bought it before I got a machine gun license. It came with a suppressor, and I paid $200 for the gun and suppressor, $200 for the stamp tax for the gun, and $200 for the stamp tax on the suppressor. I paid $600 for the package. There was a guy from Tampa who was a machine gun dealer. He didn’t have a shop, he was a collector who had quite a few machine guns and ran a Class 3 business on the side. I didn’t shoot it – we were at a gun show where he had it. He gave me the Form 4 paperwork, and I went and got the paperwork signed off immediately. Nothing really caught me about it except that it was affordable and it just looked like something fun to shoot. After that, I got an FFL and paid the Class 3 Stamp. The first gun that I bought under that license was an MG-42 from InterArms, and I really got ripped off on that because this guy had bought it from InterArms and he had resold it to me for a whopping $300! It was mismatched too.

SAR: Disgusting. You must have felt terrible. [laughter]

Knight: Yeah, but not anymore. Wish I could find MG-42s for that price now. It was one of the InterArms mismatched guns with wire wrapped around the buttstock to hold the buttstock together. It had been arsenal refinished. I had trouble finding ammo, but it ran fine, and it was fun. That was how I got started in Class 3, and that was probably in ’73. The Vietnam War was still going on, but it was winding down. I was chasing Stoner parts. I knew what I was looking for, and I just found people here and there with parts. I had found some belt feed parts, and I built other belt feed parts to complement the ones I had. The Houston Gun Show was where you’d really find all the parts. Back then that was the Knob Creek of the machine gun community. We’d find parts and pieces, and then we would finish them up or try to make them work. We didn’t have any drawings to work from. I guess I started going to gun shows in the ’60s. That Houston show was the classic of all classics, our favorite at the time. We also went to Ohio for Ohio Gun Collectors Shows. I went to Atlanta sometimes, and the big show in Florida was the Lakeland Gun Show. I had some traveling buddies, Pedro Bello, John Ciener, the local cronies that were gun nuts. We all kind of hung around together and traveled to shows.

SAR: This would be right around the time of the MAC auction in 1975. Did you know Mitch Werbell?

Knight: Pedro Bello knew Mitch, and I never will forget riding up with Pedro up to Georgia in his pickup truck. Some things in life stick in your mind vividly, and I remember this very well. I had three machine guns to my name, and I sat there next to Pedro, I had a Class 3 machine gun dealer’s license, and there I was sitting at the MAC auction. I had also just gotten paid for a big citrus contract, and I had $50,000 with me – cashier’s checks in $5,000 increments. They were selling the MAC 10s. They started off, and they sold a few, but when it really got in the heat of things, when they were really trying to move them, they would put a pallet of 100 on the floor, and say, “We are not going to take one dime less than $600.” I don’t mean $600 apiece; I mean $600 for the 100 MACs. I said, “Pedro, how can I go wrong at six bucks apiece?” He said, “Those guns will be bookends, don’t buy them, you can’t get magazines, they’re no good, you don’t want them.” In two days at the auction, I ended up buying 750 machine guns and silencers, and I spent $11,000.

SAR: Did you keep any for bookends? {Laughter}

Knight: I still have some, so I guess if I wanted to… Anyway I bought everything I could. I bought every prototype silencer they had, I bought Reisings, a bolt Remington 700, and I never will forget, we went from there over to Mitch Werbell’s house, and Pedro introduced me to him. Of course Mitch was walking around and just having a ball because the auction had all gone off so well and he was at odds with Military Armament Corp. Mitch had his M134 Minigun for sale at his house for $600, just the receiver, and I passed on that because I figured I could never get the parts. Fred Rexer was there, and Fred came over to me and he looked me in the eye and said, “Who in the hell are you, and why in the world would you buy those machine guns?” And I said, “I just did it because I could.” He was mad because he had put in a full bid for everything and individually everybody’s bid ended up being more than his total bid. Of course he would not bid against himself to get individual pieces; it would be bidding against himself. He actually gambled on winning the whole thing, and he got nothing. Fred was just absolutely livid. Looking at how machine gun values went, I still like to tell everybody that I see that knows Pedro that Pedro cost me my first $1 million, because I could’ve bought $50,000 worth where I only ended up buying $11,000 worth. Jonathan Ciener was there at the auction. Ron Martin bought all the MAC11 .380s which went for $50 each and InterArms bought almost all of the 9mm MACs. Most of those 9mm MACs went overseas. If memory serves me right, there were about 10,000 MACs total, .380s, 9mms and .45s. The majority of everything was .45s, and there were probably less than 100 .380s MAC 11s.

SAR: Were some of those MAC 10s export models without a threaded barrel?

Knight: Actually, I don’t think so. I think people converted them afterwards. In order to export the MACs, the government made them take the threads off the barrel. I think it was a company called Swift Shops that did that later as they were going to export MACs and no threads for silencers were allowed. Our government didn’t want silencers exported or guns with the ability to accept a silencer. They took the threads off the end of the barrel and cold-blued them on the front.

SAR: How long did it take to get the paperwork done from the auction?

Knight: The paperwork was only about seven days. The interesting part is the ATF just came along and confiscated what they wanted for downtown, and I had gotten some of the really nice, consecutive serial numbered, high polished blue MAC 10s and MAC 11s. ATF confiscated some of my guns and simply did not approve the paper. Back then I didn’t know enough to complain. They just cherry picked the things that they wanted out of the auction. There was a ton of interesting parts and raw material they sold at auction as well. There were bolts, and stocks and all the internals. The ATF would not let them sell any of the parts for the silencers and they made them destroy those. The material they built the wipes out of, there were big sheets of that, and they made them destroy that. That indicates even in 1975 they had an idea that silencer parts were to be considered contraband, or at least had that attitude.

SAR: It wasn’t until 1981 that the suppressor parts were blocked from sale. I know Mitch used to sell silencer parts to whoever was doing whatever. It was a straight over the counter sale and any number of Class 2s in the early to mid 1970s bought their parts at Military Armament Corporation.

Knight: There wasn’t a law to prevent it, but ATF would not let the bankruptcy auction sell any silencer parts. In the MAC auction, the ATF had wanted all these machine guns and everything destroyed, and the bankruptcy judge said, “No, these are legal to own and they’re guns that are manufactured, and they can sell these.” The Bankruptcy judge had full control and if it was legal to sell, he was going to sell it. On another note, one of the RPB (Robie, Pitts & Brugeman, the next manufacturers of the MAC series) guys had been the shop foreman for Military Armament Corporation. I’m sure he was there and bought all the MAC tooling, and bought the machine guns in the flat, and RPB finished those. He knew how to continue the manufacturing process. I bought the very first guns from RPB; I have guns one through five in every caliber for the RPB production. I was good friends with them when they first started off building guns. They’re first production was taking the MAC flats and re-stamping them “RPB” on the other side of the receiver. These are called the “RPB Overstamp MACs.” I have very good examples of the entire MAC series machine guns, and some of the stock of MAC-10s left as well.

SAR: In this same timeframe, you had been making some Stoner parts and gathering up whatever you could find, but you hadn’t found any large caches yet.

Knight: The caches came later. Around 1974-5, I was doing my police combat shooting, and I was involved with the Secret Service teams. One of the guys from Secret Service had gone to SEAL Team Two, and they showed him these Stoner belt-fed machine guns that were inoperable, and he said, “Well, I know a guy down in Florida that works on those and has some parts and pieces, and you need to call him.” SEAL Team Two called me and wanted me to go up to see what they had. They had a conglomeration of 63s and 63As that were all hodge-podged, and they had mixed parts from 63s into the 63As and 63As into the 63s. Most of the guns just did not work. I took all their guns apart and repaired and rebuilt all their guns, as much as could be done. They had used those extensively in Vietnam, and they’d brought back all the stuff, but the guns weren’t supportable because the factory wasn’t building any of the new parts. I had the parts in stock, and I put all their guns back together. That’s way before I even knew that if you do the work, you were supposed to charge the government. I figured that out later. {Laughter} That’s also when I really saw my first pistol suppressor. The SEALs had what was called a “Hushpuppy,” a Smith & Wesson Model 39 that was converted by Smith & Wesson and had a little aluminum silencer on it with a rubber package that let the bullet go through it and trapped the gases inside the silencer. When they added a slide lock on it, and when the operator unlocked the slide and tried to jack the round out and put a new round in, the extractor would climb out over the cartridge case, and the cartridge case would stick in the chamber. They thought that that was some kind of a “vapor lock” (That was the term the SEALs used), and I later determined that the ammo they were using was manufactured by Supervel, and was way up on the high end of SAMMI specs for what was functional. They were using a heavier bullet, making that 9mm go sub-sonic, and of course at that time, in the early ’70s, no one had really perfected sub-sonic 9mm ammunition. It’s not as simple as just putting in a heavier bullet. I did a whole lot of experimenting and found out that as the slide went back, the barrel on the 39 unlocked by moving down, and as the barrel moved down, the extractor came over the cartridge rim and the extractor would leave the cartridge stuck in the chamber. I went and got a whole bunch of Beretta 92 series that used an extractor that was a larger size and a straight motion, they pulled the cartridge straight back as it unlocked. I threaded in the barrels and put their silencers on Beretta 92s and solved that problem. I also loaded 50,000 rounds of 9mm with a 170-grain bullet that they could also use in this suppressed pistol package. I built the Beretta 92s in 1978-79, and the special subsonic ammunition was in 1981-82. I only built about a dozen and all went to the government except my “keepers.” My first contract with the government was around 1974 when the government had wanted to fix the Stoner 63s, putting a block in the front of the trigger, and I took and built a little dust-cover for the Stoner 63 for all the guns. Crane bought a bunch of parts so they could rebuild their guns. I also built wooden handguards for the Stoner 63, so they could convert rifles to machine guns. To this day you still see some of my wooden hand guards that people think are original and I’m the only guy who knows that they’re not. I did a real good job of copying Cadillac Gage’s work.

(Reed’s son Trey has been quietly prodding his father on some issues in the Interview, and at this point Trey suddenly remembers this event and gets indignant.)

Trey: Hey! That’s right! You know, he gave me ten cents apiece to sand them. I didn’t know I was getting ripped off. I was just a kid!

Knight: Yeah. [laughter] I gave you ten cents apiece and you were darned happy.

SAR: How can you tell the difference between those forends? We’re going to start a new edition of Stoner collector frenzy here.

Knight: These were the Stoner 63 LMG handguards, and we built them out of the same wood that the originals were made from. We used the same steel bushings, everything was the same. The difference is that the original Cadillac Gage wooden forends had a sling swivel at one end, and ours did not, because the Navy SEALs didn’t want a sling that hooked to the hand guard. After that, I was rebuilding their Stoners, trying to keep them running, and I’d run out of parts. I went everywhere looking. One day, I said to myself, “There’s got to be a bigger stash of parts somewhere.” These didn’t just to dry up. I had heard that this guy by the name of Eugene Stoner had a house in Florida. I looked in the phonebook, and I found him in a little town just south of mine, just north of West Palm and south of Fort Pierce. I called him and I said, “Is this the Gene Stoner that worked for Cadillac Gage?” And he said, “No, this is the Gene Stoner that worked as a consultant for Cadillac Gauge,” and I said, “Well, I’m repairing some of the Navy SEALs’ guns, and I’m looking for parts and pieces, and is there any way that I can get any parts?” He said, “I have all that stuff, but I’m down here in Florida. If you want to come up to my place up in Port Clinton, Ohio, I’ll entertain showing you the parts and pieces and what have you.” It was late 1978, maybe into 1979. Trey says I “tricked” the family that we were going on a family vacation and that is what I told them. We all piled in the Dodge van and drove up to Port Clinton, Ohio, and we met Mr. Stoner. He took me into this warehouse that had big holes in the roof, and there were seven or eight semi-loads of parts, and all the tooling for the Stoner 63. I got a handful of parts I wanted and invited him to visit me in Florida. He came up a couple times and had lunch with me, and we talked, and I’d go down to his place, and we would have a lot of fun, just going out to lunch and talking. He was not really doing anything as he was between programs. At that time he had just gone to Iran and sat down with the Shah, who said, “We want an anti-aircraft gun to shoot down those Iraqi aircraft.” Stoner said, “I can build you a gun, and I can build it for anti-aircraft work,” and the Shah asked how long it would take. Stoner said “I’ll send you a proposal,” and they had a very nice, cordial meeting. As Stoner’s getting ready to leave, one of the assistants to the Shah came up and handed Stoner a check for $1 million. In those days that was pretty tall money, and the Shah had Stoner’s attention. The Shah said, “I want you to get started on this program, and I want you to send me monthly reports, and I want you to tell me how far you are and keep me posted. As you tell me what you spend, I’ll refurbish that money, but here’s your first draw, and just keep going on this thing, and let’s get this program underway.” Stoner was actually being directed by the State Department to do this project. One of the things that I later found out is they didn’t really want to sell the Iranians our best US anti-aircraft technology, but they wanted to sell the Shah good technology. Stoner basically had the very, very first of the laser-tracking systems that he built on his “Eagle” system, and was quite successful at building this twin 35-millimeter, high-velocity anti-aircraft system. We spoke quite a bit in that period. We’d talk about other things that he was working on, what he was doing in Ohio at Ares. His main projects were cannons and the 75mm and 90mm smooth bore, long rod penetrating, case telescoped ammunitions.

SAR: Were you still racing?

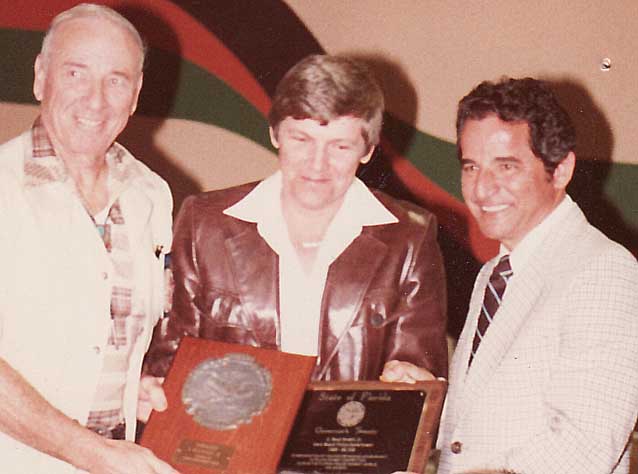

Knight: No. At that time, I was really focusing on my main work; I was in what’s called the hedging and topping business, in the citrus business. I also had a garbage company at that time, yes, before you jump on that Dan, I was actually a garbage man. {Laughter} I just hadn’t made up my mind what I really wanted to be when I grew up. I wasn’t racing, but I was always an avid shooter. For ten years I won the Florida State Championship for the number one on the Governor’s 20, which was the top 20 revolver/pistol shooters in the State of Florida, consecutive, up until 1981. I wasn’t doing archery anymore, but guns were always around. I had a big pile of machine guns. I was an FFL dealer, doing business, but I was also working towards the collection that was my passion. Regarding the firearms business, other than dealing, I had been working on silencers for the Berettas and Hushpuppies. Right about 1980, I basically started working very close with the government to develop better silencers for them. I also went all over the country looking for parts and pieces for the government. They wanted certain types of guns and certain types of ammunition, and I was kind of a go-to guy to get things for them.

SAR: This is the same timeframe you started working with Dick Marcinko? (Richard Marcinko, the “Rogue Warrior” of SEAL Team Six and Red Cell fame.)

Knight: That’s affirmative. I didn’t know all the details at the time, but I was read into a then-to-be secret program that this individual was going to go out and build a bunch of equipment and put together a team for counterterrorism. This later became Dev Group. I went all over the country finding parts and pieces, and getting guns and things that they could use to do their job. I sold to the Navy, and I sold Marcinko the first Beretta 92s that the government ever bought. Later I traded the 92s back and gave them 92Ss. These were all Italian pistols. Some of these I altered for slidelocks and suppressors. The early years of this were all pretty wild. Carrying guns and ammo to Little Creek in the back of that same old Dodge van I had, pulling a U-haul trailer behind it filled to the top with guns, and getting there and dropping them off in this warehouse in Little Creek, Virginia, walking over to this other warehouse and a guy handed me a check, then I’d leave and go back home to Florida. I was a contractor, and doing business with them.

SAR: Did it make you money in those first deals?

Knight: Gas was a lot cheaper then, and I did make money, but this was all exciting. I traveled a lot for shooting, but very little overseas. I worked a lot through InterArms and some of the other companies that had product that I could buy and import. I was not like Sam Cummings and the people who were really international-type people. I was such a low denominator and so low on the food chain in these deals. I know I made some money and had a good time. I learned a lot. I was “drinking water through a firehose” back then. It was certainly exciting because I was working for all the high-end people. I remember one day I was up at Beltsville, the Secret Service facility, and these guys came over and said, “Listen, we need you to go talk to somebody,” and I said, “Okay.” So we went into this room and we sat down and this guy was there chomping on a cigar, and he’s sitting there looking at me, and he said, “Listen,” he said, “I understand you’re doing some work for my buddy, Marcinko,” and I said, “Well, yeah, I have.” He said, “Well, I really want you to come to work for me.” And I said, “Okay, I guess I could. Who are you?” He said, “I’m Charlie Beckwith, and I have a need for what you do,” and I said, “Well, I’m your guy.” Charlie had heard about all the work that I’d done for Marcinko, and of course, Beckwith and Marcinko were rivals, they both wanted to be on top of the hill. I’m sure that everybody that Marcinko had, Charlie tried to steal, and everybody Charlie had, Dick tried to steal. I started working for Charlie Beckwith in the early ’80s, at SOTF, the Special Operations Training Facility.

The two Navy SEALs that I repaired the Stoner 63s for, one was Fly Fallon, the other was Ken McDonald. They were the armorers at SEAL Team Two. They had served in Vietnam with Marcinko. When Marcinko stood up at Dev Group, he basically picked five guys, including himself made six. Ken McDonald basically knew me from work me in the arms room, and that’s how my connection had got there. Fly had started working for Special Operations Group Two, which was basically the early WarCom. At that time there was SEAL Team Two, SEAL Team Four. Fly did all the weapons testing. Fly was actually the Navy SEAL that did all the testing on the M-60E3, which was a lightweight M-60. He also did all the early testing of the very early Minimi, and the HK262. That’s where I got into all the early weapons in the ’70s, when all those systems were being tested. Fly served up until almost until his death. He had gotten “Agent Orange’d,” and about seven years ago he died from cancer.

SAR: Reed, here we are in the early 1980s, and you’re running a bunch of different, diverse businesses that don’t have much connection to each other…

Trey: Selling guns to the Navy SEALs was probably a lot more fun than hauling trash and trimming trees.

Knight: I was still in the citrus hedging and topping business, and yes, selling guns to the SEALS was pretty exciting. In 1981 I started a supply company for the police departments in the State of Florida, and the name of that company is Lawmen’s Shooter Supply. We were a distributor for Smith & Wesson, Remington, and Winchester. I sold handguns, body armor, light bars, car equipment, holsters and whatever they needed. I started off kind of small with three or four employees. I had a retail store at 3801 Okeechobee Road in Fort Pierce, Florida. Trey started working there when he was 11 or 12 or so. It was kind of a family business.

Trey: That was my first exposure to the firearms business, getting behind the counter and selling guns.

Knight: I actually worked there too, that was my day job. I was driving around to different police departments doing trade-ins and straight sales. We would trade guns, we would bid on guns, we would do light bar demonstrations, we would go all over the state and sell guns. I got some good trade-ins, did a lot of good business with a lot of good departments. Basically, grew that from a startup company, it’s still in business, and now my oldest son, Trey, still runs and manages that company, with 25 employees. We basically just stay in the state of Florida. We had other people that we competed against that, they stayed in their territory and we stayed in ours, it just made sense. This is also about when I went to the Knob Creek Machine Gun Shoot for the first time.

SAR: Did you go there when it was tents outside, or when it was the pole barn?

Knight: The first year or so the show was in tents. I guess that would be in 1986 or so. Right after the 1986 law change banning manufacture of machine guns for private ownership. After they put the pole barns up, I would get some tables with friends and go there to shop for firearms and parts we needed, and sell some Stoner 63s. It was always a good time. I still like to go there when I can, to shop, see what’s there, see old friends.

SAR: Regarding finding Stoner 63s and parts, you went back to Port Clinton with Gene Stoner and made a deal….

Trey: I remember when. It was13 tons of parts and tooling, seven tractor trailer loads that all had to be loaded, sorted, stored.

Knight: Yeah, they included the tooling and everything else in the deal we did. That was much earlier than 1986. I guess it sets the stage for where we were. I was collecting that stuff just to keep it, to supply parts for the Navy SEALs, to have inventory. I thought that I might build a gun one day and actually made 100 pre-1986 transferable Stoner 63As. I saw the end of the machine gun world coming and like everyone else I built whatever I could. 100 Stoner 63As, some Steyr AUGs, some HK trigger packs, a few M134 Miniguns, and even some Remington 1100 machine guns in 12 gauge. There was a window of opportunity of about 45 days from when we knew the law was coming at us, to when it took effect. It was quite a frenzy in the industry, and some people that were based in the civilian market turned out a tremendous amounts of items. On the Stoners, I was interested in preserving and keeping up with the tooling. There were only maybe two dozen Stoners that the SEALs would try and keep going by this point. It wasn’t like it was a big, monumental effort on my part or their part. In 1982, there was an RFP out on the street for suppressors for the M16s that the Navy was going to build, seems like it was 3,000 suppressors for the M16A1s. The silencer had to meet certain thresholds – of so many rounds a minute for such a period of time, had to be submergible, had to meet all the military Navy specs. In 1982, we won that contract, and delivered those suppressors to Crane Naval Weapon Support. It was our first major suppressor contract. We had sold a couple dozen here or there in the past. As has been noted before, there’s a difference in a “sale” and a “Contract.” This was a full size “Contract.” This was the Navy Model, from Knight’s Armament Company. I built a few extra; I probably sold 100 other than that on the civilian market, and they were all stainless steel. The flash hider was removed and the Navy Model was screwed on, and had a tapered split collet that clamped onto the barrel that kept the silencer straight, and it also kept it from unscrewing off into the barrel. It extended back over the barrel. It was an inch and three-quarters in diameter, and about seven or eight inches long. Our delivery time frame was six months, and we met the deadline.

SAR: What were you doing for sound testing in that time period? There really wasn’t a solid protocol.

Knight: I had bought a B&K 2209 sound meter from Don Walsh (Larand). Mickey Finn (Qual-A-Tec) was testing suppressors, and Don and I were testing them. We got together and said, “Okay, this is how we’re going to standardize things. We’re going to test this at one meter from the muzzle, at 90 degrees to the muzzle, and we’re going to use a 4136 microphone, and the B&K 2209 meter, Peak-Hold, but A-weighting.” Basically, Crane followed us and their standards, and we set up what became the Mil-Standard for A-testing used today. Our combined experience with sound level testing led us to choose the 2209 meter with that particular microphone because of the very fast rise time, and for the high sound pressure levels with firearms.

SAR: When did you meet Don Walsh?

Knight: I met Don in the mid-’70s, probably around maybe ’76, ’77. All that period of time I was doing work with the suppressors and the Navy SEALs. Everyone knew all the cast of characters in the business at that time. It was a small, closed community with a closed customer base. Kind of a parallel sales situation. Some of the people concentrated on selling to the civilian market or a little bit to law enforcement, but the community that was actually selling to the government was very small. It still is, no matter what the marketing hype might be. When I said “Cast of Characters,” I meant that it was an interesting group. Mickey Finn was the first one to coin the term “investors” in this industry, in that he went out and got a bunch of people to put money into his business, and they did a lot of R&D and took a new style of write-off. I was funding all of my work out of my back pocket. They really got a leg up on us and they really built some great products. That was in the ’79-’80 timeframe, when we were very heavily involved in the suppressor development work for the government, doing different things: .22s and 9mms, and MP-5s and integral suppressors. Most of that was nickel and dime stuff and nobody had any real large major contracts at that time. That first Navy contract was pretty much the largest contract that had come along out of the military for a number of years since the Vietnam era. Testing at that time was still based on the Frankfurt Arsenal-style testing. Our new protocol moved things up to a higher level. It was still an analog system, it hadn’t moved to the digital system, but it was so much further ahead then because it was a defined parameter. How you measure the sound of a gunshot, because it is so transient, is very important on what type of rise time you use, and also what kind of microphone you use, and what kind of distance you use away from the sound source, as well as angles. All of those things, when you define them, and we all started using the same “ruler” to measure something it became so subjective so we could accurately understand the effects of our suppression techniques. Especially on products like the Hushpuppy-type suppressor, because the sound is over such short period of time, but the peak of that sound is higher. A Hushpuppy-type suppressor with a rubber-type baffle or wipe system actually shows on the meter at a much higher level of sound than other suppressors, but because the sound source is for such a short period of time, you actually hear the bullet hitting the wipes as the source of the sound, not the muzzle blast. On many wiped designs, it’s the bullet strike that’s getting the noise level that you actually hear. That being said, the Hushpuppy was quiet to the ear, but it showed a 127 dB on the sound meter. If you would compare it to a non-wipe system, it would be probably about 122 dBs, and you’d look at that and you’d see that five or six-dB difference, and that was 100% noise difference, but the Hushpuppy sounded quieter to the ear. We really perfected the rubber wipe suppressor in what we called the “Snap-On.” We actually built a little aluminum can with the rubber baffle stack for pistols. Because the suppressor was so light and it built pressure in this chamber, it negated the need for a Nielsen-type device, and the gun/suppressor system became very reliable. The Beretta happens to be the gun of choice in this type system, because the barrel does not tilt, the action just goes straight back.

SAR: You do have a tremendous passion for the history and technology of military small arms. Would it be fair to characterize your experiences though as living a little bit in the civilian world of ownership, but living mostly in the military and law enforcement community in your designs and manufacturing?

Knight: I guess we’re always trying to identify what we want to be when we grow up. I have crossed over in the communities, looking for balance and diversity to get companies through the hard times. We all want to be something, or aspire to be something. My inspiration has always been for making better equipment for our servicemen, and building good equipment, and improving the tools that they have to do their job. It’s not all good times though. I remember in 1990, waking up one Monday morning and having a big mortgage on a brand new factory that I’d built, and not having one government contract in-house at all. They were completed. That was quite frightening because I looked at the mortgage and I had made a major commitment to it when I had had some very large government contracts, and it looked like they were going to last forever. I had committed when we had three major contracts hit all at one time. I was building silencers for the Beretta M9 for the Air Force, about 5,000 of them. I was building helicopter gun mounts for the H-53 helicopter, and both of those contracts were running concurrent with each other. I also had another very large classified contract of delivering product that was right after that. With three of those contracts, it looked like we had “arrived.” We were now, in my opinion at the time, a major military contractor, because we were certainly able to do the work. I had another business that I mentioned earlier that was a company called Lawmen’s and Shooters’ Supply Inc. That company was very, very stable. We were doing good sales, we were making a decent profit, but the Lawmen’s and Shooters’ Supply Inc. ended up, from time to time, covering the payroll for the research and development that we were doing over there in the other side of the house. When we got these good contracts for these large deliveries, I did not have any way to manufacture what was needed. I started going to the tool shows and looking at manufacturing methods to be able to manufacture this equipment that I had sold to the government. I ended up buying new CNC machines and developing processes. From 1986 to 1988, we became a pretty serious manufacturer. I owned two or three CNC lathes and two or three CNC milling machines, and we were learning on how to “manufacture” as opposed to “filling small contracts.” Big difference. Then, like I said, there is the day when everything is done and you’re looking at that big mortgage, no open contracts, and you wonder, “What do you want to do when you grow up?”

SAR: Knight’s was making suppressors, some larger mount pieces, and some other accessories. There had to be a point where you had an inspiration for a rail system.

Knight: One of my very good Navy SEAL friends had gotten tangled up into his parachute going into Panama and drowned wrapped up into his parachute cord. I thought, “I need to help make their load lighter.” I noticed that in the pictures and on TV that they had taken their flashlight and taped it to their hand-guards with duct tape. I thought, “That’s not going to stay lined up and it’s going to hit on doors, and it makes the rifle bulky.” I thought, “What if we had a way to put that flashlight on and off the gun easily and compactly?” I played around a little bit with what we called the “Lego,” nicknamed after the toy company product that allowed you to clip things together. I had no idea that this thing was ever going to be used for holding anything other than a flashlight. I built flashlights that went underneath the rifle, and vertical pistol grips. I built flashlights that went on the side of the rifle. I built all kinds of flashlight mounts, and converted a lot of already existing MAG lights to brackets and mounts that attached to guns. Our first goal was to take an already existing firearm and modify it to make this “rail system” that parts could plug onto. We took the thing to Colt, and other manufacturers, and I said, “Hey, I got this idea. I’d like to show you this, and I’d like for you to build it,” and I remember meeting there at Colt, and Rob Roy said, “Is there a requirement for this?” I said, “What do you mean by requirement?” He said, “Does the government have a need for this?” I said, “Yeah, they have a need for it.” He said, “Well, is there a written requirement?” I said, “They don’t even know they don’t have this yet, but there is a need for it.” So he said, “Well, you go get a requirement for this and we’ll build it for you.” I said, “If I go get a requirement for this, I’m not gonna need you. I need you now, I need you to go help me sell this.” They all said, “Well, we just don’t think that there’s a need for it, and we don’t think there’s a requirement for it.” I had been doing a lot of work with Colt because I built the muzzle brake on the Advanced Combat Rifle, the ACR program. So I knew everybody at Colt, and they knew me, and they’d been down to my factory and I had a relationship with them that was a very good and strong.

SAR: They just didn’t get the vision.

Knight: In retrospect, it took forever to get the government interested in it. They really didn’t know that they really needed it. Remember, I was selling it as a mount to hold a flashlight. I remember talking to Gene Stoner about it one time. I said, “Why in the world didn’t you give me a place on this M16 that was square to the bore, so that I can mount something on that would always be parallel to the bore?” He said, “Well, what is it that you wanted me to mount? What is it that you have in mind that you’re going to mount to this?” I said, “Well, like maybe a laser,” and he looked at me and he said, “Yeah, in 1958 I was thinking about a laser.” {Laughter} I said, “I guess you’re right, you didn’t have any need for that at that time.” I remember in the early ’90s sitting in a meeting with a colonel who was briefing people and he said, “I believe if they put one of these rails on a butt stock, somebody would buy it.” I was in the back of this room filled with the industry people, and I raised my hand and I said, “Sir, did I understand that to be a requirement?” {Laughter} It was a joke at the time, but today it might not be a joke. I’m sure somebody’s thinking about it.

The hardest thing to do was not modifying the existing rifle, but to have those rails to stay in alignment for the total life of the shooting of the rifle for its total life. The rail system had to withstand the wear factor, it had to withstand the recoil factor, the heat factor, and all the other adverse conditions as well as be soldier-proof. We had to build it so it didn’t make the gun any heavier, it didn’t change the point of impact, that it didn’t take any tools to put on, and that it could be put on at the user level rather than having to come back to the armory to install. I remember sitting in the first meeting, we were negotiating, and I said, “You guys aren’t even asking for the most important part of this rail system, which is the vertical pistol grip.” They said, “We don’t need that. We don’t have a requirement for it.” I suggested they do some testing. They had just finished up with a simulator that they had just built for the ACR program, and they had just spent umpteen millions of dollars of testing that equipment against the baseline of duplex rounds and different things. The simulator rifle actually recoiled, and you had to acquire the next target. About two months later they came back to the colonel and he said, “You know something? We have found that that $39 vertical pistol grip that we put on your gun increased the hit probability for every soldier type, experienced soldiers, non-experienced soldiers, all types of shooters, significantly more than the whole $32 million that we spent on the ACR program.” The $39 piece that they added to the M4 and the M16 increased the hit probability more than all the training and testing they did with spending and development on the Advanced Combat Rifle.

SAR: So just getting your rail system on there and putting your front grip on it—

Knight: – Gave a better than 20% improvement to hit probability, which was the goal of the ACR program. What they really said that was significant is that the people that had the most improvements were novice shooters who had a much better hit probability increase than experienced shooters. Experienced shooters knew how to hold the gun, knew how to shoot and what have you. I remember being at Fort Benning one year, and I was there with a group of people, and this sergeant came up to me, he said, “You’re Reed Knight, aren’t you?” I said, “Yeah, I am.” He said, “I just want to shake your hand,” he said, “I train thousands of people here in basic training in the shooting skills, and every time I get a shooter that does not qualify, I can give them one of your vertical pistol grips, and they always qualify afterwards. That one piece of gear has made more difference in people qualifying in military shooting than any other piece of gear that I’ve ever seen come through here.”

SAR: That’s pretty satisfying.

Knight: It was great. It was also satisfying that this was something that the government didn’t even want and I had called it right and gotten it approved. Actually, in my infinite stupidity, when we were negotiating on the rail system, I said, “You don’t want the vertical pistol grip? I’ll throw it in for free.” Obviously it was included in the price with all the other stuff, but at the same time, when I added it to the kit, I didn’t increase the price for the vertical pistol grip. That was the RIS (Rail Interface System), our first product in 1992. It was a USSOCOM purchase. The RAS (Rail Adapter System) was an almost concurrent requirement. The Army tested the RIS first, then tested the RAS, and wanted some changes made. At 5-6,000 rounds with their testing style using a bore rod, the point of impact had shifted out of the specification on the RIS. We developed the RAS, and spent another $250-300,000 developing that product. Six months of development, really a very strong program, and we submitted it. They tested it and said, “It didn’t do any better than the RIS.” That was a shock. I asked how they tested it. It turns out they were testing with a bore rod down the bore like they had on the RIS, and the bore rod had gotten worn out, that it became out of synch, and they didn’t have a baseline. We showed them how we tested it, and they adopted our test procedure and re-tested it, and they said, “You know something? Your first one would’ve passed also.” We had ended up spending a lot of our own money to give them a different product, and that’s why we always look carefully not only at our own products, but what the customer’s test protocols will be.

SAR: You were putting a great team together in the ’80s, and today you’ve got a good team to design and build the products that you decide to take on.

Knight: One of the things that I’ve been very fortunate on is that even though I’m not an educated engineer, I’m not an educated business manager, and I’m really not an educated pretty much anything, I have been able to associate myself with some very, very talented people. I have been able to find people that have the same passion that I do, or they have come to me. We have been able to take the ideas and the needs of a customer, and take those needs and to build solutions to those needs. My talent has probably been to think outside of the box. Gene Stoner told me something interesting one day; he said, “I believe when you become an engineer, and they teach you the disciplines, you learn that one and one make two, and that you have to do it this way because this is what the book says to do. I think it prevents you from becoming a true designer. If I sometimes knew what the engineering math was on some of my designs before going all the way through with them, I probably would’ve quit earlier.”

The Knight Interview continues in the next issue of Small Arms Review, where Reed discusses the MK23 suppressor program, SR-25, The SASS, and more.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V12N5 (February 2009) |