By Frank Iannamico

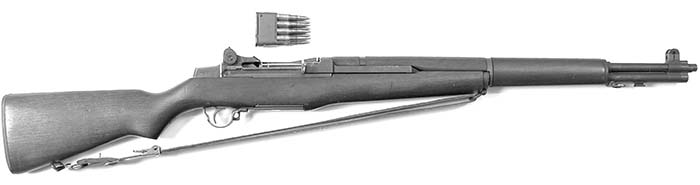

There have been many accolades bestowed upon the World War II performance of the semiautomatic Caliber .30, U.S. M1 rifle, better known as the Garand. The U.S. had prudently adopted the M1 rifle back in 1936. During the ensuing years the weapon was continually being developed and improved, resulting in an exceptionally reliable weapon by December 1941 when the U.S. was suddenly plunged into war. The United States’ M1 rifle was by far the most successful semiautomatic service rifle fielded in World War II. Russia and Germany also fielded limited numbers of semi-auto rifles, but none of them could compare to John C. Garand’s M1.

Despite its stellar reputation, the M1 rifle did have a few shortcomings, such as its enbloc 8-round clip that made a distinct sound when ejected, and the rifle’s propensity to jam during a heavy rainfall. Work had begun during World War II to fix the weapon’s various problems as well as provide the rifle with a select-fire capability. During 1945 a select-fire, magazine fed Garand designated as the T20E2 rifle was briefly adopted as a limited procurement item. However, the end of the war curtailed all interest in the weapon resulting in the cancellation of a contract for 100,000 of the modified Garand Rifles.

There were only two concerns that manufactured the M1 rifle during World War II; the U.S. Government Springfield Armory and the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. By the end of World War II the total production of M1 rifles was 4,040,802 weapons, a wartime production figure second only to the M1 carbine. All during the war there numerous upgrades and modifications being implemented into the rifle. When hostilities ended in 1945, M1 production was suddenly terminated, and the Springfield Armory began to receive shipments of well-used M1 rifles to upgrade, rebuild and place into long-term storage.

On 25 June 1950, the North Korean Army stormed across the 38th Parallel on the Korean peninsula into South Korea marking the start of the Korean War. The U.S. took quick action under the United Nations flag to assist their South Korean allies and basically fought the war with same small arms issued in World War II. The same U.S. weapons were also supplied to the South Korean army. As the war dragged on a need for additional service rifles became apparent. Despite the continued work on a select-fire, magazine fed service rifle, none were manufactured for issue. Instead, the government decided to resume production of the stalwart M1 Garand rifle. The Springfield Armory, who had produced a large number of M1 rifles during World War II, began to remove its vast array of M1 tooling and machinery from storage. During 1951, preparations for resuming manufacture began, however the monthly rifle and spare parts production rate was nowhere near that achieved during the Second World War.

International Harvester Company was awarded a government contract for the manufacture of M1 rifles at their Evansville, Indiana plant on June 15, 1951. The company’s primary business was the manufacture of commercial trucks and farm machinery. Although the company was seemingly an odd choice to manufacture a service rifle, experiences during World War II had proven that American companies, especially those who had mass production assembly line experience, could easily adapt and produce excellent small arms, and in large quantities. The location of the International Harvester plant was also considered to be geographically advantageous, due to the growing post World War II fear of a nuclear attack on North America. Small arms manufacturers like the Armory, Colt, H&R and High Standard were all located in the New England area and could theoretically be wiped out in a single strike.

The Line Material Company of Birmingham, Alabama was granted its first government contract for the manufacture of M1 rifle barrels on April 30, 1951. The barrels were marked LMR for contractor identification and were used on International Harvester rifles and were, on occasion, supplied to the Harrington & Richardson factory.

The Harrington & Richardson Arms Company of Worcester, Massachusetts received a government contract for 100,000 complete M1 rifles and spare parts on April 3, 1952. There were several contract amendments issued for additional M1 rifles from H&R. Harrington & Richardson was a well established manufacturer of sporting arms, and had produced the Reising submachine gun during World War II, and on into the 1950s for police sales. They would also become a primary contractor for the U.S. 7.62mm M14 rifles.

The adoption of the M14 rifle and 7.62mm NATO cartridge on May 1, 1957 would signal the end of the M1 Garand’s long reign as the standard U.S. service rifle. M1 Rifle production continued until May 17, 1957 when the last service grade M1 emerged from the Springfield Armory plant.

Original World War II configuration M1 rifles are quite uncommon, due to the Ordnance Corps rebuild and upgrade programs. The exclusive use of corrosive caliber .30 ammunition during World War II also resulted in the replacement of many of the rifle’s original 1940s dated barrels. An original configuration 1940s era M1 is able to bring quite a premium price in today’s M1 collectors market. This situation has resulted in a growing collector interest in the M1 rifles manufactured during the Korean War. Many original Korean era M1 rifles can be found in good to excellent condition, because most were actually manufactured after the Korean War had ended. Despite a production run during the 1950 to 1953 war era, most of the M1 rifles used during the war were refurbished weapons of World War II vintage.

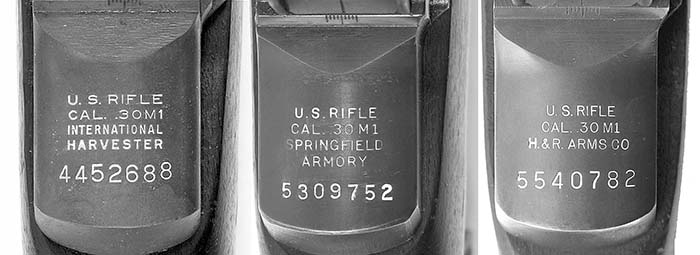

Springfield Armory rifles manufactured during the 1950s era will have serial numbers beginning in approximately the 4,200,000 range. Like the World War II era Springfield rifles, the receivers were marked with the Springfield Armory name. The barrels and parts were marked SA and the barrels were also marked with a 1950’s date of manufacture. The stock cartouches on early manufacture rifles would be SA/JLG to designate the Army Inspector of Ordnance Colonel James L. Guion. After 1953, rifles of Springfield manufacture would have been fitted with a stock stamped with the Defense Eagle stamp enclosed inside 1/2-inch square box also known as the DOD stamp. Total production at the Springfield Armory from 1952 through 1956 was 661,747 rifles.

International Harvester M1 rifles had at least four separate varieties of receiver marking configurations, due to the subcontracting of some of the company’s receiver manufacture. Barrels found on International Harvester M1s are usually those of the Line Material Company marked with the letters LMR. Parts manufactured by or for International Harvester were stamped IHC. All stock cartouches were the Defense Eagle stamp enclosed inside 3/8-inch square box. International Harvester produced 337,623 rifles from 1953 until 1956.

Harrington and Richardson M1 rifle receivers were marked H&R Arms Co. Barrels and other parts were marked with the letters HRA, although there is evidence that during production some H&R M1 rifles were fitted with barrels supplied by the Lines Material Company (LMR). All H&R stocks were stamped with the Defense Eagle cartouche enclosed inside 1/2-inch square box. The company manufactured 428,600 M1 rifles from 1953 to 1956.

There are certainly enough variations of post-World War II M1 Garand receivers, parts and barrels to interest the purist collector, as well as today’s average shooter/collector.

Below: Markings on a Springfield Armory (SA) M1 rifle barrel manufactured during October, 1954.

M1 Garand rifles were at one time difficult for collectors to obtain resulting in the salvaging of many demilled receivers by welding remnant pieces back together. During the 1980 period many M1 rifles and other U.S. small arms were allowed to be re-imported back to the U.S. as many of these rifles had been given to friendly countries as military aid. Many of the re-imported rifles came back from Korea, their condition being anywhere from good to poor. One government import requirement that turned many collectors off was that the barrels had to be marked with the importer’s name and address. Sometimes this was tastefully done with small letters; others used much larger fonts that greatly distracted from the gun’s appearance. Another source for M1 Garand rifles has been the Civilian Marksmanship Program; more commonly known as the CMP. The CMP offers M1 rifles in various grades direct from U.S. Government stores. Both of the rifles available from these sources are commonly referred to as “mix-masters,” meaning that the rifles were assembled from parts from different manufacturers and eras. This is a common virtue among U.S. weapons that have been repaired or have undergone Ordnance rebuild programs. The CMP does however occasionally offer “collector grade” M1 rifles, although these generally sell out very quickly. Another source for collector grade M1 rifles is from M1 expert and author Scott Duff. Scott has written many articles and books on the M1 rifle and is highly regarded among the M1 collector community. He posts his rifle offerings monthly at http://www.scott-duff.com and they usually sell out very quickly.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V10N1 (October 2006) |