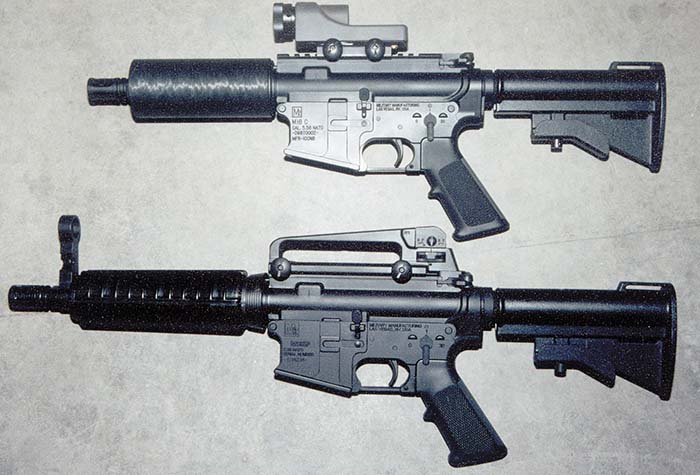

Military service rifles in the U.S. and abroad have historically almost always been followed by the issuance of smaller, lighter carbine versions. Shown here: the U.S. M16A2 Rifle (top) and the U.S. M4 Carbine (bottom).

By Jim Schatz

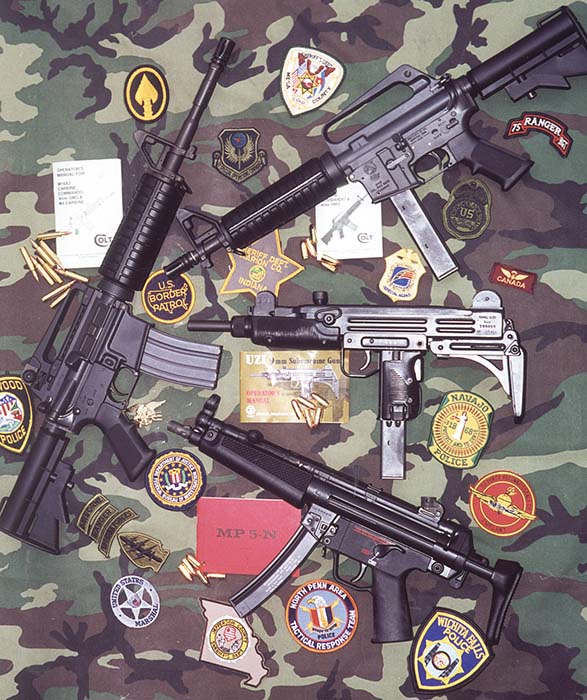

Over the past 15 years there has been a quiet but fundamental change in the weapon of choice for Close Quarters Battle (CQB) by military special operations and law enforcement tactical personnel. This trend away from pistol-caliber submachine guns for CQB has not been confined to the shores of the United States. In fact, many of the current rifle caliber CQB weapons available today are foreign designs, a few notable ones from the former Soviet Union. Why the change and what has it brought to the tactical community? Why has this change occurred now? What events and lessons learned have driven special units, tasked with armed combat at close ranges, away from their trusted and dearly loved submachine guns? This article will explore these questions and discuss current trends in CQB weaponry today.

The trench broom. The Submachine Gun

Submachine guns, for the purpose of this article, in the true American definition are defined as shoulder-fired weapons firing true pistol cartridges such as 9X19mm Luger, .45 ACP, .40 S&W and 10mm Auto as well as many other calibers of non-U.S. origin. Submachine guns in service in the United States military historically have been used primarily as short-range and defensive weapons during most of the conflicts of the 20th century. Over the past two decades the submachine gun in conventional units, mainly the WWII era M3 and M3A1 “Greasegun”, have been relegated to duty with tankers and MP’s, with a few notable exceptions.

During the 1970’s with the advent of modern terrorism and hostage taking aboard airliners, trains and other such linear targets with confined working space for assaulters, the pistol-caliber submachine offered “the shooter” a small, lightweight weapon with a large magazine capacity. These basic physical attributes made and still make the subgun perfect for counter terrorist team members moving quickly to and through these targets. The successful employment of submachine guns by Israeli Commandos in Uganda, by the then newly formed German GSG-9 Anti-Terrorist Unit in Mogadishu and the British SAS in 1980 at the Iranian Embassy in London maybe did more to propel the submachine gun into the modern CQB role than all of the tactical advantages of the weapon.

Because of their inherent handiness, subguns can quickly be brought to bear on single and multiple targets, only second in speed behind handguns. They can be presented fast on target and can swing quickly from one target to another in the highly fluent CQB environment so many special operators live and die in today. Firing pistol rounds they impart little felt recoil to the shooter and thus offer excellent controllability. Their pistol cartridges offer reduced maximum range and ricochet hazards and controlled penetration around fellow team members and innocent bystanders. Standard pistol ammunition fired from these weapons does not generally perforate protective vests of fellow team members and presents less of a hazard in the pressurized cabins of aircraft in flight.

Pistol cartridges fired from the large capacity magazines (20 to 50 rounds), normally common in modern submachine gun designs, offer a large amount of rounds “on board” available to the shooter before the need to reload. SMG’s are also easily sound suppressed with proven and highly effective accessory sound suppressors. Their limited muzzle blast is easier on fellow team members operating in confined spaces than rifle- caliber fire and is more conducive to use with night vision devices. Modern subguns are also well known for extremely long service life, including barrels and sound suppressors. Many HK MP5’s and Uzi’s have had more than 300,000 rounds fired through them without the need for a barrel exchange. Service life of the CQB weapon is an important factor for the high volume shooters within most elite units.

The Winds of Change

With so many advantages offered by pistol-caliber submachine guns, why the need for a change to something else? As is so often the case in modern warfare, whether it be military warfare on the battlefield or warfare by law enforcement officers against well- armed criminals on our city streets, developments in small arms are often brought on by actual failures and deficiencies of current hardware in actual real life operations. A good example of this is the current effort by the U.S. Army to lighten the force, making it easier to move quickly to all parts of the world. The heavy 60+ ton main battle tanks developed during the 1970’s and 80’s to fight the former Warsaw Pact tanks and APC’s on the open plains of Europe are now to be replaced with lighter vehicles that can be airlifted and airdropped into the “operations other than war” we so often find ourselves involved in today. These changes are brought on not always by foresight but by reaction to current events.

The relatively newfound popularity of the Mini Assault Rifle owes its heritage to lessons learned in CQB operations where pistol-caliber submachine guns revealed their inherent deficiencies of limited range and terminal effects, especially against targets wearing body armor.

A Brief Historical Prospective

Throughout the history of U.S. military small arms where there existed a full size service rifle very often a shorter lighter carbine followed closely in its footsteps. Springfield Trapdoor carbines, carbine models of the .30-40 caliber model 1896 Krag-Jorgensen rifle, the Tanker version of the M1 Garand, all more portable versions of the larger service rifle with nearly the same range and terminal lethality. The same is certainly true of the rifles chambered for the 5.56X45mm NATO cartridge known commercially as the .223 Remington. Not long after the adoption of the AR15/M16 rifle for Vietnam in 1964, “shorty” carbine and even “submachine gun” variants of the now famous Eugene Stoner designed rifle began to emerge from the manufacturing facilities. The XM177E1 and E2, the CAR-15 used during the famous Son Tay Raid in 1970 planned to free American POW’s in North Vietnam, the Air Force GAU-5 and even the contemporary U.S. M4 Carbine being issued to U.S. forces today follows the same development downsizing of earlier U.S. service rifles. Why? For ease of transport, to lighten the load of the soldier, to address unique mission specific requirements of specialized units without appreciably effecting the ability of the user to effectively engage targets within reasonable combat ranges. Today the 6 pound 5.56mm U.S. M4 Carbine with a 14.5 inch barrel, or some variant of this weapon, is issued to not only special operations forces in all branches of the U.S. military but also to conventional units as well, such as the 18,000 man 82nd Airborne Division.

The Submachine Gun versus The Assault Rifle

During the 1970’s and 1980’s the world began forming what we recognize today as the modern counter-terrorist and hostage rescue units of the world, the Delta’s, SEAL Team 6’s, GSG-9, and SAS CT Wing along with many other units like these. Like Delta and its sister unit (and predecessor) “Blue Light,” many fledgling CT units started life using existing general issue weapons, in the case of Blue Light and Delta, M3 Greaseguns and CAR-15’s. Soon, through experience and by the means of increasing special operations equipment budget, these units quickly adopted 3rd generation submachine guns for the CQB missions for which these units have become so well known.

The HK MP5 Submachine Gun has been the choice of nearly every such unit for the past 30 years. Like the men and units that carry and have carried it, the MP5 is fast and deadly, just the ticket for the “targets” of today, terrorist holding innocent hostages on passenger ships, in high profile buildings and “planes, trains and automobiles”. However unbeknownst to most readers, in the mid-1980s the exclusive use of the MP5 for CQB in military special operations units would begin to change. When the targets changed so did the tools to remove them.

With the proliferation of modern soft and “hard” body armor, brought on in part by the end of the Cold War, terrorists and conventional enemy personnel more frequently protected themselves against many pistol-caliber weapons in use by special units around the world by employing modern body armor. Even though special armor piercing ammunition was developed to deal with these ballisticly hardened targets, many teams failed to adopt these special types of enhanced cartridges. In the U.S. in fact, the adoption by the military of the FFV/Bofors armor piercing 9X19mm NATO ammunition for use in the U.S. M9 Pistol and to a lesser degree in the HK MP5 submachine gun was prohibited by the U.S. Government (Clinton administration) to “keep it out of the hands of the criminal element”. (This was done not withstanding the fact that most high velocity deer hunting cartridges loaded with conventional soft-core projectiles will defeat soft and many hard types of body armor).

Modern body armor has found its way into the hands of criminals in the former Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and in the United States in a few highly publicized police shootouts with well-armed and equally well-protected bad guys. Pistol caliber carbines and submachine guns simply do not possess the penetration, long range performance (100 meters) and pinpoint accuracy required to defeat targets wearing modern body armor or protected by vehicle windshields and body panels.

Military and Law Enforcement requirements differ

For the military, the move to 5.56mm CQB weapons away from the 9mm MP5 in most cases was driven by a unique operational requirement that is not normally a concern of federal or local law enforcement. Law enforcement tactical personnel are most often provided a secure perimeter around the target by their own support personnel in which they operate. They can then generally move to and from the target in relative safety not having to fight their way in and out or watch their backs. Military units very often operate within “Indian country” with little or no assistance on the ground from outside friendly forces. They are generally responsible for their own security getting to and from the target as well as their actions upon arrival at the objective. Lessons learned in operations in Grenada, Panama, during Operation Desert Storm and Somalia reinforced the fact that, like taking a knife to a gunfight, you shouldn’t take a submachine gun to a rifle firefight.

In most cases hostage rescue teams operating independently behind enemy lines fight with only what they can carry. Whereas an MP5 makes a great gun for CQB use inside the target building or ship, it is woefully outmatched across open terrain against enemy personnel armed with AK47’s, G3’s and captured M16 rifles. It is probably this lesson more than any other single factor that propelled the military special operations units in the U.S. towards rifle-caliber weapons for most of their missions, including those previously handled with the submachine gun.

For some time during the 70’s, 80’s and into the 90’s, military assault teams and hostage rescue units often brought along a separate security element armed with assault rifles to escort and protect the subgun-equipped assaulters to and from the target. In a few cases some units actually carried assault rifles to get to and from the target and MP5’s for the actual assault of the target. Things got so ridiculous that some military Special Reaction Teams actually carried two U.S. M9 Pistols on CQB missions because 9mm submachine guns were unavailable and 5.56mm M16’s were simply to large and unwieldy within the close confines of the classic CQB target.

Finding the right tool for the job

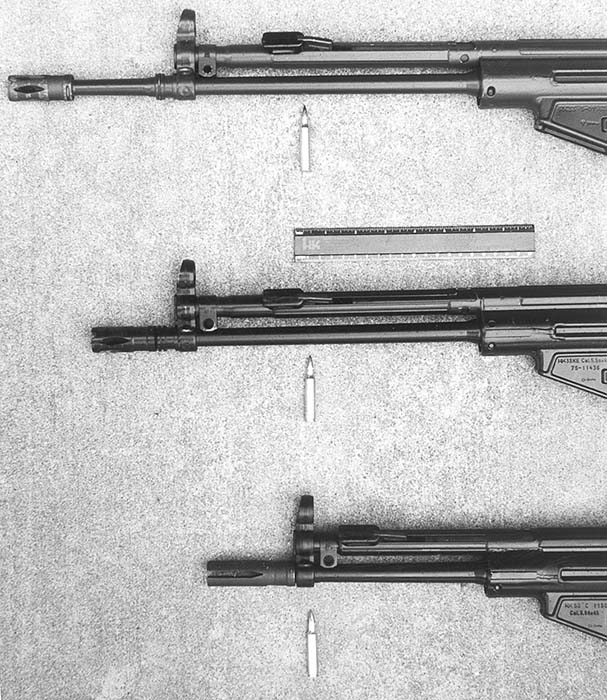

In recent times beginning in the mid-1980’s, the more elite U.S. special operations teams began to search for solutions to the deficiencies of their current small arms for assault and CQB use. Teams evaluated smaller, more compact long guns in rifle calibers 5.56mm and 7.62mm as potential replacement of 9mm submachine guns. In the end the 5.56mm select-fire carbine, like the Colt CAR-15 and M16 Commando and the HK33K and HK53, was found to be the nearly ideal compromise between being small and handy and yet powerful enough to give the user a fighting chance against aggressors armed with assault rifles themselves.

Rangers Lead the Way

As has been so often the case in the last half of the 20th century, where military special operations go with new small arms developments, the law enforcement community is soon to follow. As military special ops and federal law enforcement tactical teams often operate and train together, both with their foreign and domestic counterparts, the federal agencies are often a few years behind the military special units in adopting the newly emerging military equipment trends. As the feds begin using new weapons, state and local agencies are exposed to them and they also soon find a home in the local law enforcement tactical team. This has been the classic case with the HK MP5 submachine gun. First used successfully in Europe by military and paramilitary special units, the weapon spread across “the pond” to special U.S. military units and then down through federal and ultimately into local law enforcement organizations. After more than 30 years in the U.S., the MP5 still sells very well to local law enforcement tactical teams for Close Quarter’s Battle. However, in the world of the U.S. military special operations, and to a lesser degree, in federal law enforcement, the submachine gun for all but special missions (VIP protection, special assaults on board ships, personal protection or sound suppressed use) has been replaced or is being replaced by a host of 5.56mm Carbines and even more compact 5.56mm weapons.

You can’t fool Sir Isaac Newton

The laws of physics apply, even to special operations units. In the 1980’s 5.56mm carbines were about as small as that caliber and category of shortened rifle would allow. While there were a few obscure short-barreled 5.56mm weapons even smaller than CAR15’s and HK33K’s, such as the HK53, Ruger ACC556, and LaFrance M16-K, few were well known and even fewer had a proven reputation for reliability. In the past if you wanted more performance from your CQB weapon by going to a rifle cartridge you got a larger, often heavier less user-friendly weapon. It was a trade off — performance for portability.

Very recently this trend has changed with the development of an entirely new and separate category of small arms that this writer will describe herein as a Mini Assault Rifle. To define such a beast one must first consider the definition of an assault rifle. By its classic definition, the modern assault rifle today has all of the characteristics of the world’s first true assault rifles developed by the Germans during the final years of WWII. The Mkb42(H), the MP44 and STG45B where “Sturmgewehrs” in the classic sense. Firing an intermediate cartridge smaller than the full power service rifle cartridge but vastly more capable than any pistol round, the assault rifle fired in both semi and full auto modes. Assault rifles are generally always shoulder fired and feed from box magazines or drums (normally detachable) and are smaller and lighter in weight when compared to full size service rifles.

The service rifles of the U.S. Armed Forces today, the M16A1 and M16A2, are full size assault rifles. The U.S. M4 and special operations peculiar M4A1Carbine, by definition, is a shorter, lighter version of the full size assault rifle with a shorter collapsing buttstock and more importantly a shorter 14.5 inch barrel versus the 20 inch barrel of the M16A1 and A2 versions. For the purpose of this discussion, the Mini Assault Rifle would have all of these features as listed above. It would operate like the full size assault rifle and carbine yet would fit more in the class of a submachine gun by way of barrel length (10 to 12 inches or less), overall length (under 30 inches) and weight (under 7 pounds).

Jane Says there is such a beast, and lots of them

Mini Assault Rifles are not really new, it’s just their popularity is a recent thing. A quick look through the rifle section of Jane’s Infantry Weapons will revel more than 20 such animals, one or more variants available from most parts of the globe. In fact, this writer was able to identify 27 rifle-caliber weapons that would meet the definition of a Mini Assault Rifle. The combined listing is in the 1998-99 edition of Jane’s Infantry Weapons and Charlie Cutshaw’s authoritative work on Soviet Small Arms entitled The New World of Russian Small Arms and Ammunition (1998 Paladin Press). This number compares to only two such entries in the same Jane’s reference work from1988-89. Many of the earliest and more advanced Minis are those originally created for the Soviet Special Forces, MVD and SPETsNaz units, during the 1980’s and 1990’s. Perhaps this is another reason that the Miniature Assault Rifle has been so strongly embraced in Western special units in the past 15 years.

It is clear in some cases that even the manufacturers of these micro-sized assault rifles did not know where to categorize them and what to call them. HK Germany has called the HK53 with it’s 8.3 inch barrel a “submachine gun” for many years because of its diminutive size even though the classic definition of a submachine gun cannot include weapons chambered for rifle-caliber cartridges. The Russian 5.45mm AKS-74U, arguably the most widely available Mini, is a sexy little assault rifle often seen in the hands of special military and police units, especially those providing personal protection for high profile dignitaries and VIP’s. The Krinkov as it is often mistakenly called (not used by the Russians to describe the weapon) has often times been labeled as a “submachine gun version of the AKS-74 rifle “ by the world’s small arms experts.

The sharp increase in the worldwide availability of the Mini Assault Rifle certainly speaks to the demand that has developed around the globe for a small weapon with maximum performance. Today one can find such small wonders in calibers 5.45X39mm Russian, 5.56X45mm NATO, 7.62X39mm Russian and even 7.62X51mm NATO as well as the relatively new high performance 9X39mm cartridge developed by the former Soviet Union for such compact guns.

What vacant role does the Mini Assault Rifle Fill?

The answer to this question is actually fairly simple and straightforward. For those users that want most (80%) of the exterior and terminal ballistics of a 5.56mm carbine or full size assault rifle in a small, easily portable and maybe concealable package, the Mini Assault Rifle is the answer. No existing pistol-caliber submachine gun can provide the ballistic performance of the rifle-caliber Mini Assault Rifle. This includes muzzle velocity and energy, maximum effective range, ability to defeat soft and some hard body armor types with conventional ammunition and a host of other rifle caliber specific attributes. Many of the modern Mini Assault Rifles on the market today are as small or smaller than the pistol caliber submachine guns like the HK MP5A3, and a whole lot more lethal, and at greater ranges. It is almost a perfect combination. Or is it?

Advantages and Disadvantages

There are many advantages to using rifle-caliber entry weapons. But like my favorite law of physics, for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. With advantages come disadvantages. Again, there is another trade off to consider. While the terminal performance and range superiority of a rifle-caliber CQB weapon exceeds that of all pistol-caliber weapons, it does not come without a price. Rifle-caliber weapons generally exhibit increased felt recoil and thus can be harder to control, especially when using fully automatic fire. With the high velocity cartridge comes excessive and an often brutal muzzle flash and blast, especially in confined spaces. The essential communication between team members becomes almost impossible. Adding sound suppressors to the weapons will address this problem. However, very often these muzzle devices cost as much or more than the host weapons and have a limited service life before needing replacement. They also add to the overall length and weight of the complete system reducing the all-important quick handling attributes of this tactical tool. Sound suppressors also foul the interior working parts of the weapon much faster. They can adversely effect the reliable operation due to increased backpressure within the weapon system and most often accelerate the wear and tear and parts breakage compared to running the gun unsuppressed. It is also more difficult to fully suppress rifle-caliber weapons, especially for select-fire operation, as reliable subsonic ammunition is just now beginning to be perfected for CQB use and presently, in most cases, is very expensive.

General barrel life on rifle-caliber weapons ranges from 10,000 to 20,000 rounds compared to that of over 250,000 to 500,000 documented rounds for the pistol caliber submachine guns like the MP5. Thus, generally, the overall initial system purchase price and lifetime maintenance cost of the rifle-caliber CQB weapon will be higher than the comparable pistol-caliber weapons. Rifle-caliber weapons also tend to destroy training apparatus and shooting houses far faster than pistol-caliber weapons, thus there will be additional costs to building and maintaining these facilities. Though catching up with the submachine gun, rifle-caliber weapons are just now being offered with the desired features of a CQB weapon as well as the critically important accessories such as tactical lights, rail mounting systems, modern reflex sights and durable sound suppressors. Special purpose ammunition for the-rifle caliber CQB gun is now available in many specialized flavors beyond the 55 and 62-grain military rounds used for the past two decades. This includes frangible, subsonic, specialized CQB and match grade ammunition.

The muzzle velocity versus penetration argument

Overpenetration is seldom a concern of the military special operations teams as long as the lethality of the round is not compromised. This is not the case with law enforcement personnel who most often must account and answer for every single round fired. In recent years numerous experts within the field of small arms ammunition and forensic science, to include many law enforcement agencies across the U.S., have pooled their resources to conduct studies to determine the wounding and lethal efficiencies of rifle versus pistol-caliber ammunition for CQB applications.

Few would question the statement that in almost all cases and for many reasons, the projectiles launched from rifle cartridges are generally more lethal than those from pistol cartridges. While it takes more than the muzzle velocity and energy of a projectile to wound and kill through the disruption and utter destruction of tissue, few, if any, pistol rounds even come close to matching the specs of rifle cartridges, especially at extended ranges (> 75 meters). However, one of the more surprising findings coming from these studies reveals that in many cases projectiles fired from pistol-caliber weapons actually penetrate further through soft tissue and building materials than do high velocity rifle projectiles, in particular 5.56X45mm NATO. The reason can simply be explained that high velocity rifle projectiles are inherently unstable at normal short-range CQB distances (< 50 meters). They tend to yaw, or tumble, rather than drive straight through close targets and building materials as one would think. Experts have thus recommended a minimum of 2,800 feet per second muzzle velocity for 5.56mm CQB weapons, performance normally acquired from barrels in the 14 to 16 inch length. Pistol cartridges, especially full metal jacketed ball projectiles and even hollow-points bullets plugged with bits of clothing, have a propensity to overpenetrate tissue and building materials. Because of their comparably slow velocity, pistol bullets often do not fragment and cause multiple wound channels, as is often the case with certain rifle bullets.

The ever-increasing worldwide popularity of the Mini Assault Rifle with barrel lengths of less than 10-12 inches indicates that not every user group agrees that a minimum of 2,800 feet per second muzzle velocity is required for CQB use. The development of new projectiles and cartridges that provide higher velocities from shorter barrels are developments with the Mini Assault Rifle in mind. However, a smaller more portable rifle-caliber CQB weapon is often preferred and many teams believe the threat of overpenetration by some parties has been exaggerated. Not all testing provides the same results. In fact, a great deal of effort and money has been expended to develop a subsonic 5.56X45mm round for effective use with sound suppressed assault rifles. With a muzzle velocity of less than 1,080 feet per second this round is lethal and yet considered perfectly “safe” in respect to overpenetration. In general terms, less muzzle velocity with the same projectile weight also means less felt recoil to the shooter and thus better control. Better control can mean fewer misses, and misses are certainly as great a consideration as overpenetration in the close confines of the CQB environment where friendlies are near the intended target.

Conclusion

Thus, in the end, rifle-caliber CQB weapons can actually be more lethal and yet pose less risk for those agencies concerned with overpenetration and the endangerment of innocent bystanders. If the other disadvantages of the rifle-caliber CQB weapon, such as higher sustainment costs and increased muzzle blast and flash, are acceptable to the tactical commander, then any one of the modern, proven Mini Assault Rifles available today might prove to be the perfect CQB weapon for the 21st century.

About the Author:

Jim Schatz has been a full time employee of Heckler & Koch since 1986. He is a contributing writer for this magazine who, as part of his profession, helps to develop and provide advanced small arms to many of the most elite military and federal law enforcement organizations in the United States.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V4N6 (March 2001) |