By Jim Dickson

After designing the M1941 semi-automatic rifle, Melvin Johnson set his sights on a light machine gun version of his design. While making it accept the already issued M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle magazines seemed a logical choice, that was not an option due to Johnson’s prior experience submitting his M1941 rifle to the Army. When the U.S. Army Ordnance Department first tested the Johnson rifle, it had a detachable box magazine. According to Bruce Canfield in his authoritative work on Johnson’s firearms, “Johnson Rifles and Machine Guns: The Story of Melvin Maynard Johnson, Jr. and His Guns”, soldiers testing the rifle loaded the cartridges in the detachable BAR magazine used in the M1941 backwards. This had the effect of bending the feed lips, rendering the magazine’s operation unreliable. Johnson saw this and demanded new magazines before the test started. Ordnance refused and, adding insult to injury, counted each of the resulting magazine-induced stoppages as “malfunctions”, tanking the gun’s performance in testing on paper. Years later, Johnson’s son, Edward Johnson, suggested to me in a conversation that this was a blatant attempt to influence the outcome of the test in favor of the competing incumbent M1 Garand rifle.

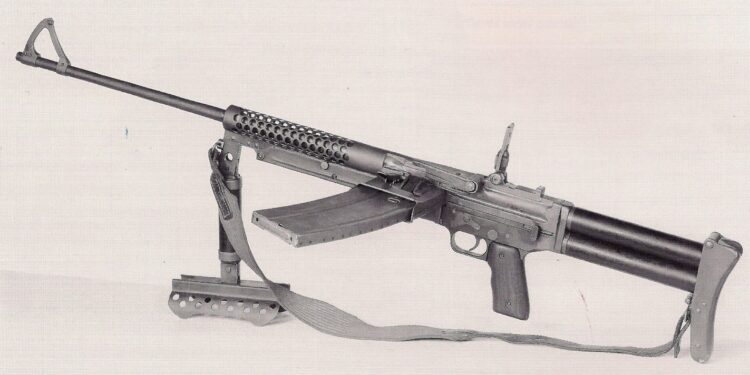

Faced with such brazen dishonesty, Johnson responded by developing a rotary magazine that could not be sabotaged in this way and that offered the benefit of being able to be topped off in use with stripper clips so that soldiers would never be caught changing magazines when an enemy suddenly appeared wanting to shoot you. For his light machine gun, Johnson added a detachable magazine to one side. He could not use a double column magazine for fear Ordnance would sabotage them and count the resulting failure of the magazines to work as the gun malfunctioning, so he developed a 20-round single-column feed magazine that was immune to such tampering. That, plus the five rounds held in the rotary magazine, gave the soldier 25 rounds at their disposal.

Johnson was well aware of the Browning Automatic Rifle’s faults. The M1918A2 was a heavy, 21 pounds and very clumsy to handle. It was gas operated with all the attendant powder fouling and jamming that goes with that kind of system. It lacked a quick-change barrel, so sustained full-auto fire was out of the question. The exposed barrel would burn you sooner or later, disassembly and reassembly was a nightmare, and most damning of all, the gun wore heavily under heavy usage, necessitating constant Ordnance rebuilds. These rebuilds, while straightforward, were often poorly done by Ordnance resulting in the troops getting weapons that did not work reliably.

Johnson set out to make a light machine gun that had none of these faults… and he succeeded. At 12.5 pounds, the weapon was still within the upper limits of what a rifle could weigh. It handled fast and sure with no hint of clumsiness. There was a ventilated barrel shroud and a quick-change barrel just like the Johnson M1941 rifle had. This was a light machine gun that could maintain sustained fire like any other air-cooled machine gun with a quick-change barrel The short recoil system of the Johnson rifle eliminated all the problems inherent in a gas-operated machine gun. It was extremely rugged and didn’t fall apart under heavy use like the BAR did. Like the Johnson rifle, it was totally reliable. Accuracy in full-auto was superior to the BAR, but unlike other weapons, the M1941 LMG fired open-bolt when in full-auto (benefitting from the 50% recoil reduction that offers) but it fired from a closed bolt when the selector was set on semi-auto for sniper rifle accuracy.

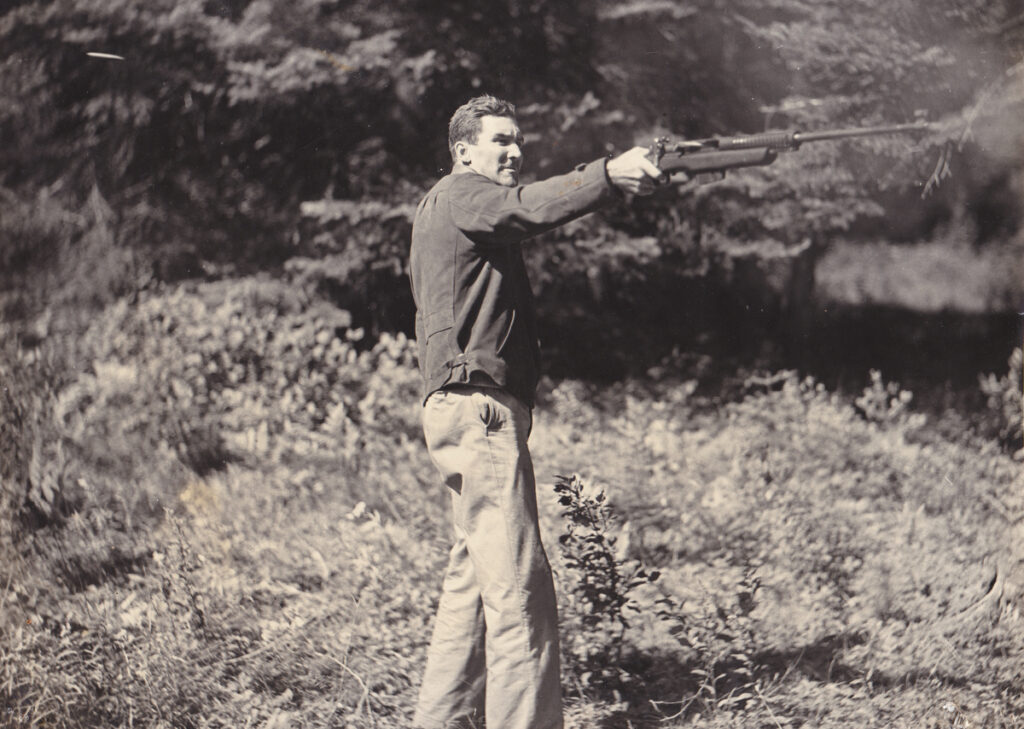

The M1941 LMG shared many components of the M1941 Johnson rifle and was actually a rifle designed to fill the LMG role. As such, it and its successor, the M1944 Johnson, remain the only rifles in history to succeed in this role. The increased speed of mobility that a lighter LMG delivers was amply demonstrated by one of Johnson’s favorite tricks, firing the M1941 LMG one-handed with his arm fully extended, as shown in the photograph. I’ve never seen or heard of anyone firing an M1918A2 BAR with one hand like that. The speed of deployment of a weapon in combat is the difference between hitting the enemy and being hit by the enemy. As a LMG is supposed to be part of a mobile squad, its mobility is a decisive factor in its effectiveness in many situations.

Since the M1941 didn’t come from Army Ordnance’s tight little clique, they immediately hated the Johnson guns — even going so far as to deny export licenses for the M1941 LMG to America’s WWII ally, Holland, in the early days of the war. However, the Marine paratroopers liked the way the quick-change barrel of the Johnson rifle and the Johnson LMG could be removed and stowed alongside the rest of the weapon making for a more compact package during parachute jumps, and they were able to get a quantity. Both the rifle and the LMG were already in production for a Dutch order. When Holland fell, these guns became available to both the Army and the Marines where they were widely loved by their users.

U.S. troops weren’t the only ones impressed with the Johnson. In Germany, Louis Stanga took it as his inspiration for the famous FG42 which was intended to replace the 98 Mauser when production permitted. Not having a hostile Ordnance Board to deal with Louis used a conventional 20-round, double column box magazine. The action was based on an improved version of the WWI Lewis Light Machine Gun and a muzzle brake was fitted. It lacked a quick-change barrel and for all its virtues, it was still inferior to the M1941 Johnson.

There were also six light carbine versions made as semi-auto rifles with a standard 10-shot rotary magazine and no bipod. Dubbed “Daisy Mae”, one of these was carried into WWII by U.S. Marine officer Harry Torgerson.

Always trying to improve his guns, Melvin Johnson determined to make the most controllable light machine gun of all time and he succeeded with his M1944 Johnson LMG. The weight went up to 14.7 pounds and the bipod and wood forend were replaced with a 1.7-pound folding monopod that served as either a vertical or a horizontal fore grip, depending on its position. This monopod proved much faster to engage and more effective than the traditional bipod. The wooden buttstock was replaced with two tubes. The top tube enabled the mainspring to have more room while the bottom tube could store a cleaning kit. There was a substantial metal buttplate that was hinged and could be flipped up to access the two tubes for maintenance. Depending on the ammunition type, the cyclic rate was anywhere from 450 -750 rounds per minute. This could also be adjusted by changing the recoil spring.

As previously stated, the M1944 Johnson LMG is totally controllable in full auto fire. By the time the 22-inch barrel has moved back a half-inch and the bolt has been cammed back 20 degrees to allow unlocking, the bullet is four or five feet from the muzzle. This also reduces the amount of powder and gas left in the barrel that typically fouls the action once the breech is unlocked. The bolt has a long throw and a long recoil spring to spread out and absorb the recoil, this is in addition to the weight of the gun doing its part to absorb recoil. The weight of the bolt and the barrel for the half-inch of unlocking travel also counts as bolt weight during that time. The result is a steady straight rearward push instead of the normal jack hammer effect of recoil in a full-auto gun that jerks the muzzle up with each shot. Fired from the prone in full-auto with the monopod deployed, the recoil from each shot is just 1.33 pounds. By way of comparison, the M16 has seven pounds of recoil per shot. Fired from the shoulder, the M1944 is still controllable. Plus, it achieves this controllability without the use of a muzzle brake that would likely cause permanent damage to the shooter’s hearing. Combining its controllable nature, its ability to fire semi-auto from a closed bolt for precise shots, and its unsurpassed reliability, Johnson may have produced the most effective one-person operated firearm of all time in his M1944 LMG.

With the selector set at semi-auto, the cycling of the action begins when the cartridge is fired. The bolt and barrel remain locked together as the barrel recoils a half-inch back into the receiver. During this travel time, the multi-lugged bolt is rotated 20 degrees to unlock by the camming arm of the bolt sliding against the camming face of the receiver. Once the bolt is unlocked, the rearward travel of the barrel is halted while the bolt continues to the rear, compressing the long recoil spring, cocking the hammer, extracting, and then ejecting the spent cartridge case. The recoil spring now drives the bolt forward, where it locks into the barrel, and the gun is ready to fire semi-auto again. This action is just like the M1941 rifle.

When the selector is set for full-auto, the cycle begins with the bolt catch holding the bolt in the open position until it’s released by pulling the trigger. It then chambers a cartridge, closes, and locks into the barrel. At this point the automatic sear is tripped, firing the round. The gun continues to fire full-auto until it is out of ammo or the trigger is released (catching the bolt in the open position.) When the last round is fired, the bolt remains closed in either the semi-auto or full-auto setting.

While the Marine Corps wanted to replace the BAR with the M1944 Johnson, this was not approved as the Marine Corps was considered a client of the Army in weapons procurement.

After the war, Johnson continued trying to get his guns adopted, even going so far as to add gas assisted operation to the guns to please Ordnance, even though this negated one of the principal advantages of his design. These efforts were unsuccessful, and it appears Ordnance was just stringing him along to offset the criticism of their scandalous behavior on this matter. The M1944 remains the high-water mark of the Johnson LMG. There has never been another non-crew-operated firearm approaching its effectiveness.