By Frank Iannamico

A problem that often confronts many people when considering buying a machine gun is what to buy. Often (mistakenly), thinking it will be their one and only Class 3 purchase, they want to take their time to be sure they make the right choice. The scope of this article is to cover some of the more popular submachine guns available to a potential buyer in the United States. We’re not covering “Borderline” items like the M2 Carbine, or the Owen, Austen, MAT-49 and early German SMGs, because they are not that common, and this article is a presentation of what the most common SMGs are in the U.S., and this is to help those new to the NFA community as they try to determine what is available.

Factors to Consider

Ammunition

Ammo is one of the primary factors that should be considered for two reasons: cost and availability. Surplus ammunition is usually the most economical way to feed a machine gun though most, if not all, come from foreign sources. In recent years ammunition has increased dramatically in price. With many calibers, the surplus supply comes and goes; a recent example is Russian 7.62x25mm. The 7.62x25mm cartridge was, just a short while ago, cheap and plentiful. However this situation has dramatically changed, with the ammo now becoming hard to find, and increasing in price. Several factors have caused this sudden shortage; conversions kits for the 7.62x25mm were made for several popular firearms, like the AR-15, to take advantage of the cheap ammo; another reason has been the proliferation of semiautomatic “pistols” like those made from surplus 7.62x25mm PPS43 submachine gun kits. Combine that with the large quantities of Tokarev variant pistols that have been imported, and there is a shortage, leading to a price increase.

Availability: many calibers used in popular machine guns are now obsolete, and no longer used by any country’s military, and thus no longer manufactured (in any great quantity). Several surplus rifle calibers that are becoming difficult to locate in quantity are: U.S. .30-06, .303 British, and 8mm Mauser. When certain calibers of ammunition are no longer available, the only other viable option is reloading.

Economics is another consideration; for example how much will ammunition cost? A machine gun firing 7.62×51 (.308) ammo is going to be far more expensive to feed than a 9mm submachine gun.

Another feature desired by many in a machine gun is the ability to easily convert it to fire different caliber cartridges. With today’s escalating ammo prices, one of the most popular caliber conversions, are those for the economical .22 caliber rimfire rounds.

Choices other than economic can be based on personal or military experience with a particular weapon, or one a relative carried while in the military. Other influences can be one’s ethnic background or a weapon seen on television or the movies.

What will be covered in this article will be some of the more popular options, available accessories, parts, and other relevant subjects.

Spare Parts

Another concern is spare parts availability and price; every machine gunner has an inexplicable need to have a lot of spares. Like ammunition, surplus parts come and go, and as they become difficult to find prices increase. Spare parts for many of the rarer weapons, like the Marlin UD-M42 are virtually non-existent, this causes a reluctance to fire such arms, for fear of breaking components; although just about any part can be fabricated by a skilled gunsmith. Yet another concern, if applicable, is the cost of spare magazines, some are dirt cheap while others, like those used in the Ingram Model 6, quite expensive.

Notes on Builds and Conversions

“Tube Guns”

During the 1980s, many older submachine gun part sets were available, less their receivers. The original serial numbered receiver was considered a machine gun and could not be legally imported. Before 19 May 1986, it was legal for a Class II manufacturer, or an individual with an approved Form 1, to fabricate a receiver, and with a part set assemble a working machine gun (after ATF approval for the individual, Class II manufacturers simply send in a Form 2 notice after the fact). The most popular submachine guns were those with cylindrical receivers that could be easily replicated with readily available steel tubing; hence the nickname “tube guns.” Some of the most common models built were the British Sten and the German MP40. While Stens and MP40s with original receivers are considered Curio and Relics, those with a newly manufactured receiver, e.g. tube guns, are not.

Semiautomatic Conversions

Also during the 1980s, semiautomatic-only copies of machine guns became very popular. Some of the most desirable were the Uzi and MP5 carbines. Many of these carbines became popular for conversion to select-fire machine guns. However, back in the 1980s there were virtually no original Uzi or HK submachine gun parts, or part sets available to use in the aforementioned conversions. Original parts, when they could be found, were very expensive. This forced many manufacturers to alter the existing semiautomatic components to function as select-fire parts. This was also a matter of economics, back in the 1980s, a converted submachine were not expensive like today. A typical converted Uzi submachine gun sold for approximately $700. Manufacturers, to maximize profits, used as many of the semiautomatic parts as possible. During that period, buyers were happy just to have a select-fire submachine gun, and knew or cared little about having “correct” submachine gun barrels and other parts. Today, submachine guns are quite expensive, and the buyers better informed. Most want conversions that are as much like the original submachine guns as possible.

Dewat

A firearm that was deactivated by welding the barrel to the receiver and weld-filling the chamber, and performing certain other modifications depending on the model. This was legal to do back in the 1950-60 time period and in the Gun Control Act of 1968 these required registration as De-Activated machine guns. The original receivers remained intact. Dewat represents “De Activated War Trophy.” These transfer without a transfer tax, using a Form 5.

Rewat

A registered Rewat is a Dewat (above) that has been “reactivated” into a functioning firearm. Firearms that qualified as Curio and Relics retain that status. Rewat represents Re Activated War Trophy. An individual can Rewat a Dewat using a Form 1 and paying the $200 “Making” tax (There is no transfer tax on transferring registered Dewats, a Form 5 is used). After approval, he then performs the work to make it a live “Rewat.” The other alternative is to have a Class II manufacturer Rewat the firearm, he does not have to pay the tax, but when he transfers it back to the owner, a Form 4 is used with $200 tax paid.

Reweld

A “Reweld” refers to firearms that have had their original receivers cut into pieces, and welded back together to form a receiver. Often pieces from several different receivers were used. The term “reweld” is inaccurate, as the rebuilt receivers were actually only welded once from a legally destroyed firearms receiver. Machine guns with welded receivers do not qualify as Curio and Relics. Many of the submachine guns that are on this list had individuals who made them by welding cut receiver parts, or making tubes themselves.

United States

Some of most popular submachine guns available to the collector are those that were made or designed in the U.S.

The Thompson Submachine Gun

The Thompson, or “Tommy Gun” is one of the most desired and popular submachine guns made. They were made in a number of configurations and models, which can vary greatly in price. Original Thompsons are all considered as Curio & Relics.

Colt Thompsons

The original Thompson guns were manufactured during the 1920s by Colts Manufacturing Company under contract with the Auto-Ordnance Corporation. There were approximately 15,000 original Colt-made Thompsons produced, all were originally 1921 models. Initial sales were very slow, and many of the 1921 models were modified in an attempt to increase sales; resulting in the introduction of the 1928 Navy Model, with a reduced cyclic rate, and a small quantity of the semiautomatic-only 1927 model. Adding an optional muzzle compensator to a 1921 Model Thompson changed its designation to a 1921AC. The asking price of a Colt made Thompson depends on condition, and the presence of all original parts. The cyclic rate of the Thompson are approximately 800-900 rounds per minute for the 1921 model and 650-750 for the 1928 version.

Pros: The Colts are the “classic” gangster era Thompson, well made and finished. Cons: Guns, parts, and magazines are very expensive. Few original Colt spare parts were made; if any original parts or barrels were replaced with military components, they greatly reduce the gun’s value. And that value is always very high. Many owners won’t fire their Colt Thompsons for fear of something breaking. Not a good choice if you are looking for a submachine gun to shoot all the time.

World War II Thompsons

The U.S. 1928A1

Just prior to World War II the allies needed a submachine gun; the only proven design available was the 1928 Thompson. The Auto-Ordnance Company was resurrected (under new management) and contracted with the Savage Arms Company to manufacture the U.S. Model of 1928A1. Due to the increasing demand, Auto-Ordnance opened their own plant in Bridgeport, Connecticut and began producing additional M1928A1 weapons. The World War II era Thompsons are not as finely finished as the 1920s era Colt guns. The 1928A1 has a cyclic rate of 650-750 rounds per minute. Unloaded weight is 10.75 pounds.

The M1 and M1A1

After production was well underway, the engineers at Savage designed a new, simpler variation of the Thompson, that was easier to manufacture and less expensive. The weapon was adopted by the U.S. and designated as the M1 Thompson; the weapon was further simplified by making the firing pin an integral part of the bolt, and re-designated as the M1A1 Thompson. While the 1921 and 1928 models could use a 50- or 100-round drum magazine, the M1 and M1A1 models could only use the 20- or 30-round box magazines. The cocking handles on M1 and M1A1 Thompsons are located on the right side of the receiver. The M1-M1A Thompsons are only slightly lighter than the 1928 models with an unloaded weight of 10.45 pounds. Cyclic rate is approximately 650-700 rounds per minute.

Pros: Military Thompsons are less expensive than Colt-made examples. Spare parts and barrels are relatively easy to find. Military box magazines in 20- and 30-round capacities are very inexpensive and drums are moderately priced. Cons: While not as pricey as a Colt Thompson, military Thompsons can still cost as much as a new (mid size) automobile. The M1 and M1A1 versions cannot accept a drum-type magazine unless they are modified with special slots, which was done by a few manufacturers back when these were relatively inexpensive. At nearly 11-pounds Thompsons are on the heavy side.

Modern Thompsons

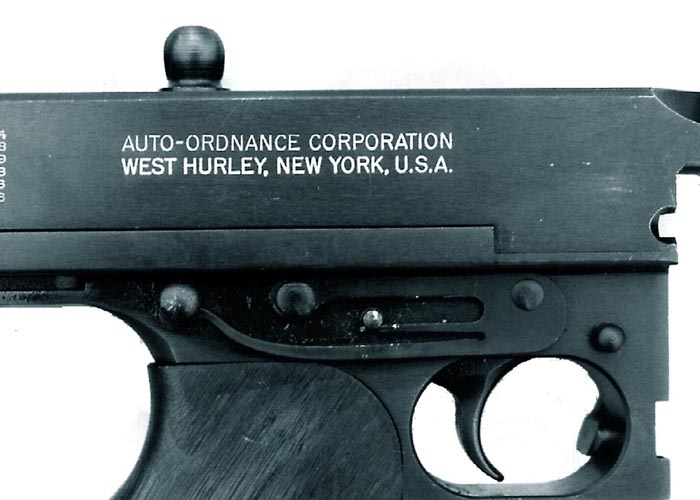

During the 1950s, the Numrich Arms Company of West Hurley, New York obtained the remains of the original Auto-Ordnance Corporation, which included a few 1928 receivers and a substantial number of parts. From these, they assembled some submachine guns and offered them for sale. These Thompsons can be identified by a NAC suffix added to their serial numbers. In 1975, when their supply of receivers was exhausted, the company decided to manufacture receivers, and use their supply of surplus parts to assemble more Thompsons and market them. These became known as “West Hurley” Thompsons, because of the West Hurley, New York address on their receivers. Eventually, the company ran out of surplus parts, and began to manufacture them in-house. The “Modern” Auto-Ordnance Company made approximately 3,306 1928 models and 609 M1 Thompsons.

Pros: Less expensive than Colt and Military Thompsons; they can occasionally be found in new-unfired condition. Both the M1 and 1928 models have been added to the Curio and Relics list. Most parts will interchange with original models. Cons: Many West Hurly made Thompsons have experienced reliably problems, often due to out-of-spec parts. However, most of the problems could be solved by replacing suspect parts with military surplus components. By this point in time, the problems with most WH guns have been solved by their owners, although this may not be the case with new-unfired guns.

The U.S. M3 and M3A1 “Grease Gun”

The .45 caliber U.S. M3 was designed during World War II to replace the more expensive Thompson, and take advantage of the new “stamped steel” manufacturing technology, inspired by the German MP40 and British Sten. The M3A1 model was conceived to address problems experienced with the M3. World War II production was by the Guide Lamp Division of General Motors. During the Korean War, the Ithaca Gun Company was given a contract to resume production of the M3A1 model and the contract was cancelled after the war ended. Despite having an original price of around $8, today transferable grease guns are quite expensive; this is primarily due to the small number available. The grease gun remained in U.S. service as a limited standard weapon until the late 1990s. Guide Lamp production from May1943 to July 1945 was 606,694 M3 models, and 82,281 M3A1s. The 1950 era Ithaca production totaled 33,227 M3A1 models. Unloaded weight is 8.15 pounds; the cyclic rate is 400 to 450 rounds per minute.

Pros: Desirable, historic U.S. submachine guns. Magazines are readily available and very inexpensive. Grease Guns are reliable because of their internal design, and accurate due to the slow rate of fire. Original military M3 and M3A1s are considered as Curio and Relics. Cons: Expensive, can cost as much as a military Thompson, slow cyclic rate of 400-450 rounds per minute (can be considered pro or con). Parts are getting somewhat difficult to locate, particularly barrels and extractors.

Medea Corporation M3 and M3A1 Submachine Guns

A few transferable M3 and M3A1 receivers were made by the Medea Corporation, of Ormond, Florida for the civilian market during 1983. The company did not offer completed guns. The receivers were sold to individuals and manufacturers; there were less than 100 registered and sold. There are usually no manufacturers’ markings on the magazine housing. The serial numbers were hand-stamped and will have a letter A, B or X prefix.

Pros: Less expensive than original grease guns, assembled with all original GI parts, except the receivers. Cons: Reliability may be a problem, as there were a number of different companies and individuals that assembled them. Not considered Curio and Relics.

Other notes on M3/M3A1 Grease Guns

Broadhead Armory registered a large quantity of receiver tubes for Grease Guns, which were disallowed by ATF. A small quantity were allowed, and they have a receiver tube instead of a welded clamshell.

The Reising Submachine Gun

For today’s collector/shooter the Model 50 Reising offers an affordable U.S. .45 caliber submachine gun. The problems encountered with the Reising in combat are generally not a concern in a civilian environment. Original Reising submachine guns also qualify as Curio and Relic firearms. Reisings can be easily found today; many have come from police departments, and have seen little use in that role. A Reising is an inexpensive alternative to a Thompson submachine gun. The Reising is a select-fire weapon that has a cyclic rate of approximately 650-700 rounds per minute. Original magazines were made in 12- and 20-round capacities. Though less common, there is also a folding stock version, the Model 55.

Pros: An original U.S. made submachine gun, which saw limited military use; qualifies as a Curio and Relic firearm. It fires from a closed-bolt and is very accurate in the semiautomatic mode. Moderately priced, and most are in very good condition for their age. Reliable 30-round aftermarket magazines are available, made by Ken Christie. Light weight for a World War II era submachine gun at 6.75 pounds unloaded. Cons: Has somewhat of a tainted reputation, but overstated. Original magazines are not overly common, and are moderately expensive; cartridge capacity is limited 12 or 20 rounds.

The MAC

The MAC-style submachine guns are some the most compact weapons ever produced; there were many manufacturers and variations. “MAC” submachine guns are generally known as “bullet hoses” for their fast cyclic rates. The rate of fire makes them fun to shoot, but not of much use for actually hitting anything that is further than 25 yards away. However, in recent years several companies have been offering upgrade kits to slow-down the cyclic rate and make the guns more ergonomic. The availability of such kits has substantially renewed interest in MAC-style subguns. The name MAC originally was an abbreviation for the Military Armament Corporation that went bankrupt in 1976. The term “MAC” has become a generic term, though often technically incorrect, when used to describe all submachine guns of its basic design. There is a language all its own for MAC owners. A “Powder Springs” MAC was made by Military Armament Corporation in Powder Springs, Georgia. A “Marietta MAC” was made when Military Armament Corporation was in Marietta, Georgia. An “Overstamp” MAC was an original Military Armament Corporation MAC receiver that was bought at the auction, and finished by RPB so it is marked MAC on one side, and RPB on the other. “Texas MACs” were made in Texas and afterwards, “Jersey MACs” were made by Hatton Industries in New Jersey. There are a lot more variants and slang model names.

The Model 10

The Model 10 or “MAC-10” was made by several manufacturers, in .45 ACP and 9mm Parabellum. The .45 caliber MACs use inexpensive M3 “grease gun” magazines, while most of the 9mm versions use the more expensive modified Walther MPL subgun magazines. The cyclic rate of these compact weapons is approximately 900 rounds per minute.

Pros: MAC submachine guns are easy to find, and are on the low end of the NFA price scale. The fast cyclic rate makes them fun to shoot. The .45 caliber magazines are inexpensive. Spare parts are easily located and usually inexpensive. The .45 caliber guns can be converted to 9mm. Cons: The original 9mm Walther magazines can be expensive. Some of the Texas-made MACs have a problem with their welds failing.

The Model 11

The MAC-11 is a smaller version of the MAC-10; it is chambered for the .380 ACP round. The original magazines are a double-stack, single-feed design made of steel. SWD later manufactured a .380 caliber M11 variant that was designed to use their Zytel magazines, called an M11A1. The M11’s cyclic rate is faster than the Model 10. The .380 caliber MAC-11 is often confused with the 9mm, SWD M11/Nine.

Pros: Very controllable on full auto, the quick cyclic rate makes magazine dumps a lot of fun. Not much bigger than a 1911 pistol. Cons: Original magazines are expensive; there are aftermarket mags that may or may not function in any particular gun. The Zytel magazines used in the SWD model are problematic. Quantities of .380 ammunition were difficult to find a few months ago, but that situation seems to be changing, however .380 cartridges are generally more expensive than 9mm.

The SWD M11/Nine

The most common of the MAC-type submachine gun series is the SWD M11/Nine introduced from 1983 until 1986. Many shooters like the small size of the M11/Nine, as well as its increased cyclic rate of fire over the M10 model. The SWD M11/Nine submachine gun is approximately 1.9 pounds lighter (unloaded) than the original 9mm and .45 ACP Model 10, but the overall length of the M11/Nine receiver is approximately .69-inches longer, to compensate for the smaller inside dimensions of the upper receiver and corresponding smaller-lighter bolt assembly. The extra receiver length is required to absorb the recoil energy generated by the 9mm cartridge. As manufactured, the little submachine gun has a quick 1,000 to 1,200 rounds per minute cyclic rate of fire. There have been numerous accessories and upgrade products made to enhance the performance of the M11/Nine, making them an extremely popular submachine gun. One disadvantage of the M11/Nine is the magazines. The original magazine designed for the M11/Nine was made of a “space age” plastic material called Zytel. This material proved to be less than ideal for a magazine and a poor replacement for simple stamped sheet-metal. Numerous problems were reported with the early Zytel magazines including splitting at the seams and their feed lips wearing out prematurely.

Pros: Inexpensive, used and even unfired examples can still be found. A number of high-quality after market accessories are available to enhance the weapon’s performance. Steel magazines to replace the Zytel originals magazines are available, as are steel feed lip kits to upgrade the Zytel magazines. Cons: The original Zytel magazines can be problematic

The Smith & Wesson Model 76

The only modern submachine gun manufactured by the famous Smith & Wesson Company; the 9mm Model 76, 9mm Submachine Gun went into series production in mid-1969. In addition to a Navy contract, the Smith and Wesson Company offered their new submachine gun to foreign and domestic law enforcement agencies. Approximately 6,000 were manufactured with production ending in July, 1974. Some early tool room models were sold, these have a letter T prefix on their serial numbers; production guns have a letter U prefix. The Model 76 submachine gun was a basic, but durable weapon primarily made from heavy sheet metal stampings. The receiver tube was produced from heavy .120 inch thick seamless steel tubing. The inside of the thick receiver tube was broached to help prevent stoppages from sand or any foreign debris that may collect inside the receiver. The appendages: the sights, magazine housing and sling loops were all heliarc-welded to the thick receiver tube. The unloaded weight is 7.25 pounds; cyclic rate is approximately 720 rounds per minute. The weapon is fed from a 36-round, wedge-shape dual stack, dual feed magazine.

Pros: Well made by a major U.S. manufacturer, select fire, easy to control, moderately priced, 9mm, qualifies as a Curio and Relic. Inexpensive Suomi 36-round magazines can be easily modified to function in an M76. Cons: Original magazines are expensive, original spare parts can be difficult to locate.

MK760

The MK 760 9mm submachine gun is a copy of the Smith &Wesson Model 76. The MK 760 was first introduced in 1983 under the company name MK Arms, Inc. The MK 760 was produced in limited numbers, primarily for the civilian machine gun market. The early models of the MK 760 submachine gun were produced in Fruithurst, Alabama, under the name Phoenix Arms, doing business as MK Arms. During 1984 the company was re-established as MK Arms in Irvine, California. Most of the component parts of the MK 760 are fully interchangeable with the original S& W M76. One of the few actual differences between the original Smith & Wesson 76 and the MK 760 is the material that the pistol grip was made from. The original Smith & Wesson grip was made of plastic while the MK 760 grip was made from aluminum and later a tough polymer plastic.

Pros: A less expensive alternative to an original Model 76, well made. Cons: Reliability problems have been reported.

Clones of the Smith & Wesson Model 76 were also made by Southern Tool and Die under the name Global arms (M76A1).

Other clones designated as the SW76 were made by Class II manufacturer Jim Burgess. One noteworthy improvement that was implemented into the design of the SW76 is the relocation of the cartridge extractor to a two-o’clock position on the bolt; this reportedly substantially reduces stress, and increases the life of the part. Many of these receivers were made to fit into other designs, using other magazines, in particular a Suomi variant.

American 180

The American 180 was one of the few successful submachine guns to be made in .22 caliber rimfire. The select-fire gun features a top-mounted drum style magazine that is available in capacities that hold up to 275 rounds of ammunition. Firing from an open bolt with a cyclic rate of fire of approximately 1,500 rounds per minute, the weapon could empty the drum in less than eleven seconds.

The American 180 submachine gun evolved from a prototype weapon known as the Model 290 designed by Richard Casull and Kerm Eskelson in the early 1960s. The “290” designation came from the unique drum magazine that held 290 rounds of .22 ammunition. Limited production of the full-automatic-only “Casull Model 290 Carbine” finally commenced in 1965 and were produced and marketed by Western States Arms of Utah. In 1969 the rights were sold to the American Mining and Development Company. Production of the unique .22 caliber submachine gun was contracted out to the Voere Company located in Austria. The Voere firm redesigned the gun for select-fire capability, and the drum capacity was reduced to 177 rounds. The American 180 was marketed in the U.S. by the American Arms International Corporation or AAI. Many of the parts to assemble the “American” 180 were imported from Austria and then assembled in Utah. Later, American Arms manufactured the American 180, this allowed the pre-1986 guns to be fully transferable. After American Arms International went out of business, production of the American 180 was resumed by the Illinois Arms Corporation or ILARCO, in hope of finding domestic and foreign customers. Since the machine gun ban of 1986 was in effect all of the American 180 models produced by Illinois Arms were post-1986 dealer samples intended only for law enforcement and military sales.

There was a brief independent production run of the AM180 submachine gun by S&S Arms of New Mexico; approximately twenty-four fully transferable guns were manufactured. These may be in odd color finishes.

The magazines for the AM180 are the drum type and consists of a drum and a spring motor. The drums come in either an original metal 177 round configuration or the later manufacture Lexan plastic in a 165 or 275 round capacity.

Pros: The AM180 submachine gun is great fun to shoot. The weapon is extremely accurate due to its lack of recoil, and can easily place shots even at 1,500 rounds per minute. Cons: The AM180 is expensive for a .22 caliber firearm, and finding spare parts can be a problem. The drum magazines are time consuming to load, and cannot be changed out very quickly.

Foreign Submachine Guns

The British Sten Mark II

Early in World War II, the British purchased a number of U.S. Thompson submachine guns from the Auto-Ordnance Company. As the war continued, the British government was running out of money, and could no longer afford the expensive Thompsons. They needed an inexpensive weapon that could be manufactured quickly. The weapon that was eventually conceived was the Sten. There were several versions of the Sten; the Mark I, II, III, IV and V. The Mark II was produced in the largest numbers. The Sten MK II has an unloaded weight of 6.65 pounds; cyclic rate is approximately 550-600 rounds per minute. Today the Sten Mark II submachine gun is common and relatively inexpensive. Like many of the other subguns addressed in this article, they are available in several configurations. The most common is the Mark II addressed here.

Original Sten Mark II

For the purist collector, there are original Sten guns available, most registered prior to 1968. In addition to the Mark II model, other versions (Marks) can occasionally be found.

Pros: Original Sten guns are considered Curio and Relics. Magazines and spare parts inexpensive and available. Cons: Can cost considerably more than a “tube gun” Sten. Magazines can cause feeding problems. A magazine loader is needed.

Sten Tube Guns

One of the most popular submachine guns assembled by Class 2 manufacturers during the late 1970s to 1986 was the Sten Mark II. There were large numbers of part sets (less receivers), and new receiver tubes were easy to manufacture. The Stens were also popular with buyers because of their low price, prior to 1986, a Sten “tube gun” could be purchased for around $200. There were a large number of Class 2 manufacturers turning out Sten guns, as well as a few individuals who, prior to 1986 after getting ATF approval, could manufacture a Sten in their garage with some tubing, a Dremel-type tool, and a welder. However, all Stens were not created equal, the quality of the builds were as diverse as the number of manufacturers and individuals who made them. The quality of any build can usually be determined by the welds, the even cutting of the cocking handle slot, as well as cutting of the: sear, trigger, and magazine well openings in the receiver tube. In some cases registered tubes were purchased from Class 2 manufacturers and assembled by individuals. Some of the more common Manufacturer names you might find would be DLO, Erb, Taylor, Pearl, Wilson, York Arms, Special Weapons, Xploraco, and LMO are a few.

Pros: Tube guns are less expensive than an original C&R example, and easily found. Magazines are plentiful and inexpensive. Sten Mark II receiver tubes can be used to build a Sten Mark V, Sterling, or a Lanchester submachine gun clone. Cons: The quality and function depends on the individual, or company that manufactured the tube and assembled the gun.

Mark V Sten Conversion

Mark II Sten receivers can be converted to the later production Mark V configuration.

Pros: Mark V Stens are more ergonomic, have better front sights, and are generally more accurate than a Mark II model. The MK V uses standard Sten magazines. Cons: Mark V part sets are less common; the conversion requires some shop skills; cutting, welding, and refinishing are required.

The Sten-ling

In recent years British Sterling part sets became available, the Sterling receivers are very similar to that of the Sten. A few Class 2 manufacturers (after receiving ATF approval) began to use registered Sten tubes to assemble Mark IV Sterling submachine guns, a submachine gun that is rarely encountered in the U.S. The marriage of a Sten receiver to a Sterling part set soon earned them the nickname “Stenling.” Most of the cocking handle slots on Sten tubes are slightly wider than that of Sterling, resulting in slightly altered cocking handles and modified disassembly procedures. A Stenling’s cocking handle and cocking handle block are modified by drilling a hole in each, so the plunger protrudes through them to retain the cocking handle. The cocking handle itself will have had metal added to it so it fits properly in the wider Sten’s cocking handle slot, and retain the bolt at the correct angle. There are a few Sten tubes that have the same cocking handle slot dimensions as an original Sterling, eliminating the modified cocking handle and disassembly procedure; such guns will usually command a slight premium over the others. A Sterling-Stenling is slightly lighter than a Sten at 6-pounds unloaded; the cyclic rate is the same at 550-600 rounds per minute.

Pros: A Sterling submachine gun is much more ergonomic than a Sten. Sterling magazines are moderately priced and more reliable than those of a Sten; however, most Sten magazines will fit and function in a Sterling. If you convert a working Sten to a Sterling, you can sell the remaining Sten parts to help cover the conversion cost. Cons: Requires a Sterling part set, and a skilled manufacturer to complete the work; a Sten to Sterling conversion can be a somewhat expensive process. Stenlings are sometimes offered for sale, but will cost considerably more than a Sten MKII.

The Lanchester Conversion

Another conversion that has received ATF approval is the Sten MKII to a 9mm Lanchester submachine gun. The Lanchester is a World War II British submachine gun, which was a copy of the German MP28 submachine gun. Cyclic rate is the same as the MK II Sten at 550-600 rounds per minute.

Pros: The Lanchester is a very accurate submachine gun, and uses standard Sten magazines. 50-round magazines were made for the Lanchester; they will also work in a Sten. Cons: Lanchesters are on the heavy side with an unloaded weight of 9.65 pounds; part kits and spare parts may be difficult to locate. The conversion is best left to a qualified Class 2 manufacturer.

German MP40 Submachine Gun

The 9mm MP40 of World War II fame is a very popular submachine gun. They come in two guises; original guns, those having original receivers, and those with “new” manufacture receivers commonly known as “tube guns.” The MP40 has an unloaded weight of 8.9 pounds; the cyclic rate is approximately 500-600 rounds per minute.

Original MP40 submachine guns were either brought back to the U.S. after World War II or imported and sold as “Dewats” during the 1950s. A Dewat is an acronym for Deactivated War Trophy. The most common way to deactivate a submachine gun was to weld the barrel to the receiver and fill the barrel.

Original MP40 submachine guns, with original receivers are the most desirable. Original receiver guns can often be identified by looking at the form that it’s registered on. The manufacturer’s block on the ATF form will list an original manufacturer’s name or will often state “unknown” or “German” for original receiver guns. Examining the inside of the receiver is another method of determining an original receiver. Original receivers will have “ribs” on the inside, the same as the outside surface, because they are made from sheet metal. Tube guns are made from a tube, and the outside is milled to contour, leaving the inside smooth.

Matching Numbers

Most of original parts in German MP40 submachine guns had numbers stamped on them, generally several of the last digits of the weapon’s serial number. An all-numbers matching MP40 is one in which all of the numbered parts match the number on the weapon’s receiver. All matching guns bring a premium over non-matching examples. The original dull blue finish is also important in determining the value of an MP40.

Pros: A World War II classic, original guns are Curio and Relics. Cons: Original receiver MP40s with non-matching parts are less valuable. Magazines prices are moderate to expensive, spare parts expensive. MP 40s are full automatic only. A magazine loader is recommended.

MP40 Tube Guns

The MP40 was a very popular firearm for Class 2 manufacturers to build using new “tube” receivers. All other parts used in assembly were usually original German parts. New manufacture receivers, made from tubing, will be smooth inside. Cosmetic “ribs” were machined onto the outside to replicate the look of an original receiver. Some manufacturers took extra care with their builds, like Charlie Erb, who marked some of the parts to match his receiver serial numbers; for an original look, he also stamped German Waffenampts (proof marks) on his receivers.

Pros: A lot like an original MP40, except for the receiver, difficult to distinguish from an original. Cons: Not considered Curio and Relics. Some manufacturers did better builds than others, a few didn’t bother to machine the cosmetic ribs on the receivers; some guns were Parkerized rather than blued.

Soviet PPSh 41

The Russian PPSh 41 (Pistolet-Pulemyot Shpagina 1941) was designed by Georgi Shpagin during World War II, and was primarily constructed of sheet metal with crude welds. Because of its fast cyclic rate of 900-1,100 rounds per minute, and 71 round drum magazine the, PPSh is an exhilarating, fun weapon to fire. The PPSh type weapons also use double-stack single-feed 35-round magazines; they are difficult to load without a loading tool. A PPSh 41 has an unloaded weight of approximately 8 pounds; a loaded 71 round drum weighs 4 pounds.

The weapon was manufactured by a number of Soviet influenced countries, all using different designations including: Poland, China, Hungary, North Korea and Iran. The PPSh 41 followed earlier Soviet designs that included the PPD 34/38 and PPD 40 that were heavier and more labor intensive to manufacture. The wood-stocked Soviet PPSh 41 was followed by the all-metal PPS43 submachine gun.

Most of the PPSh submachine guns available are original Curio and Relic weapons or “rewelds”, guns assembled from demilled original receiver pieces that Class 2 manufacturers welded back together to fabricate a functioning receiver. An original C&R example will generally cost much more than one with a welded receiver.

Pros: A lot of fun to shoot, easy to control, drums and magazines are very reasonably priced, spare parts are available; can be fairly easy to convert to fire 9mm Parabellum cartridges. Cons: The PPSh 41 can consume large quantities of ammunition very quickly; 7.62x25mm ammunition is getting difficult to find and increasing in price.

The Swedish-K

The Swedish submachine gun, commonly known as the Swedish-K, served as the model for the Smith & Wesson Model 76. The Swedish-K was used by U.S. Special Forces during the Vietnam War.

The Swedish submachine gun is known by a number of names including; the Swedish-Kulsprute M/45, the Carl Gustaf or the Swedish K. When discussion turns to the “best in class” submachine gun the Swedish “K” is usually at, or near the top of the list. The Swedish submachine gun was designed for full-automatic operation only, although single shots can be accomplished by careful trigger manipulation. The automatic cyclic rate of the weapon was designed to be from 500 to 600 rounds per minute, which is often considered ideal for optimum controllability in a submachine gun. The action of the Swedish-K is the open-bolt arrangement commonly used on submachine guns, employing the advanced primer ignition system. Unloaded weight is approximately 7.62 pounds.

The Egyptian government was quite impressed with the Swedish-K, adopting the 9mm weapon for its military forces. The Egyptian version of the Swedish-K is designated as the “Port Said” (pronounced; Sa-eed) model. Outwardly, the Swedish and the Egyptian weapons are identical and the parts are completely interchangeable. They can each be identified by their markings. The Swedish guns have the Crown and C denoting national production, some examples were clearly marked “Made in Sweden”, most of the Port Said parts were marked with Arabic characters.

The Swedish-K M/45 model was originally designed for the Suomi M31 50-round duplex “coffin” magazine. The Swedish-K was also able to utilize the forty and seventy-one round drums of the M31 submachine gun, and an excellent wedge-shaped double stack, double-feed design with a capacity of thirty-six-9mm cartridges. The reliable magazine contributed much to the success of the weapon. The magazine housing (on early models) was secured to the receiver by a steel U-shaped retaining pin, to give lateral support to the later production 36 round magazine, and could be easily removed to permit use of the Suomi 50 round duplex box magazine or either of the drum magazines.

The sights designed for the Swedish-K are considered by many to be complex for a submachine gun. The rear sight had three separate flip-up U-notch leaves calibrated for ranges of 100, 200 and 300 meters. The front sight was a protected post design that was adjustable for windage.

Although the Swedish-K submachine gun was in continuous production for nearly twenty-five years, transferable, original-receiver Swedish-K submachine guns are very uncommon in the United States. The majority of those transferable examples that do exist were assembled with “new” manufacture receiver tubes. Most of the known tubes were manufactured and registered by either Martin Pearl or the Wilson Arms Company. Many of the stripped Wilson receiver tubes were transferred to various Class 2 manufacturers who then assembled them into complete guns. Some M/45s were assembled using original Egyptian Port Said, Swedish M/45 parts, or a combination of the two.

Pros: Accurate, very controllable. Can use large capacity drums and magazines, many accessories are available including a very handy magazine loader and 36-round stripper clips, sub-caliber practice ammunition, and special training barrels. Magazines and drums are widely available and inexpensive. Cons: Original transferable examples are rare. “Tube” guns are not especially common, and are one of the most expensive “tube guns” on the market.

The Uzi

The Uzi submachine gun has become one of the most popular choices for a first-time buyer. Unfortunately this popularity has steadily been driving up the prices of transferable guns. The Uzi came in several models: full size, mini, and micro, but the full-size versions are the most common. The full-size UZI has an unloaded weight of 7.7 pounds; cyclic rate is approximately 600 rounds per minute.

Registered Receiver Uzis

Israeli Military Industries (IMI). Virtually all the transferable Israeli-made 9mm Uzi submachine guns available, with a very few exceptions, were originally semiautomatic carbines, which were converted into a submachine gun, by a number of Class 2 manufacturers prior to 1986. In order to be approved for importation, the semiautomatic carbines had to be designed so that submachine gun parts: short barrels, bolts, and trigger housings could not be easily installed in them.

During the 1980s when the conversions were performed, there were virtually no original submachine gun parts available. This necessitated the alteration, and use, of some of the original semiauto parts. As a result, many original submachine gun parts, such as barrels, bolts and sears will not readily fit in these conversions. Israeli Uzi semiautomatic carbines had a “blocking bar” welded to the inside wall of their receivers; the purpose of the bar was to prevent the installation of a submachine gun bolt. Some manufacturers left the blocking bar in place, and slotted the bolt to clear the bar. These type conversions are not very popular because the blocking bar cannot now be legally removed, and it is illegal to slot a machine gun bolt to clear the blocking bar. This makes repair or replacement of the bolt a problem.

Pros: Made in Israel, can be upgraded to most SMG specifications, parts are readily available and inexpensive. Magazines are currently very inexpensive. Recent manufacture .22 conversion kits are available. Cons: Many original submachine gun replacement parts will not fit without alterations to the receiver.

Group Industries Uzis

Group Industries was a company that manufactured a number of different machine gun receivers, primarily for the civilian market. The company also did a number of machine gun conversions, and gained fame doing a large number of full-auto conversions of the Israeli semiautomatic Uzi carbines. Group Industries also manufactured and sold a number of Uzi submachine gun parts for conversions. These were quite popular back in the days when original submachine gun part sets were not readily available.

During the 1980s, Group Industries made Uzi receivers produced on dies and fixtures they had obtained from the Belgium firm Fabrique Nationale (FN). The Group Industries Uzi was designed with many features of the original Israeli submachine gun, unlike many Israeli semiautomatic Uzi model B carbines that were the foundation for many of the converted guns. The Group grip frame was marked A- R- S, and featured the large “submachine gun” style sear and sights. The receiver was also made without the barrel restrictor ring and with a trunnion that would accept a standard submachine gun barrel. Approximately 4,050 receivers were registered prior to the 1986 ban. The Group guns were registered in 9mm/.45 ACP and .22 caliber. As a witticism, Group Industries designated their Uzi clones the Model HR 4332, this was the number of the House bill introduced by Representative Hughes (NJ) that effectively ended the legal manufacture of transferable machine guns in the United States.

After Group Industries was finally getting their Uzis on the market, a series of unfortunate circumstances caused Group Industries to file for bankruptcy. An auction was held in Kentucky on August 24, 1995 to liquidate the company’s assets. A total of 3,318 fully transferable Uzi receivers and 109 Post ‘86 Dealer Samples were auctioned off, as well as crates of parts.

Vector Uzis

The registered Group Industries Uzi receivers from the auction eventually resurfaced in the spring of 1999, assembled into complete working guns. The former Group Uzi receivers were assembled with a number of surplus South African Uzi parts made by Lyttleton Engineering. The “new” Uzis were assembled and marketed by Vector Arms of North Salt Lake, Utah. The company offered both the standard full-size and mini Uzi models. The Vector Arms Company sold the last of their new transferable Uzi submachine guns in 2003.

Pros: The Group Industry receivers and guns were made to the same specifications as original submachine guns and all parts easily interchangeable. Cons: American made receivers; some prefer the Israeli made receivers.

Registered Uzi Bolts

There were also transferable bolts registered as machine guns. Many of them were original machine gun bolts machined to clear the restrictor ring in IMI semiauto carbines and were slotted to clear the blocking bar. A registered bolt could be used to legally convert a semiautomatic Uzi to a submachine gun.

Pros: Can be moved into different receivers. Cons: Are nearly as expensive as a registered receiver Uzi. Not especially desirable. Broken or damaged bolts can be repaired, but cannot be replaced.

Registered Uzi Sears

Fleming Firearms registered some Uzi sears and these are permanently “married” to the gun that they were installed in, meaning that you cannot move the sear to a different receiver. Qualified made a small number of sears that were not married to specific receivers.

Pros: None. Cons: Broken or damaged registered sears can be repaired, but cannot be replaced.

German MP5 Submachine Guns

The 9mm H&K MP5 is one of the most desirable submachine guns available, and with good reason, they are very smooth and controllable in the full auto mode of operation. Virtually all transferable guns available were converted from semiautomatic HK 94 carbines. With their popularity comes a price, they are on the upper end of the price scale of submachine gun conversions. There were several “types” of conversions performed by a number of entities, like the Uzi conversions, there were few original HK machine gun parts available back when the conversions were legal to do. This often resulted in manufacturers altering semiautomatic parts. An original MP5 submachine gun has a cyclic rate of approximately 800 rounds per minute, unloaded weight is approximately 6 pounds, which varies slightly by specific model.

Registered Receivers

These are conversions where the receiver itself is the registered part. When the HK 94 semiautomatic carbines, on which the conversions were performed, were imported they were subject to guidelines to make the addition of submachine gun parts difficult. In the case of the HK carbines, they differed from their submachine gun counterparts, in the attachment of their trigger housings, and internal components. Submachine gun trigger housings are attached with two push-pins, the front being a swingdown pivot. On semiautomatic carbine receivers, the front pinhole area was replaced by a steel shelf welded to the receiver. The front of the trigger housing was made to slide or “clip” onto this shelf and be secured by the rear housing pin. This alteration also would not allow a submachine gun trigger pack to fit into the semiautomatic housings. As a result for select-fire conversions, the components in the semiautomatic trigger packs were altered to function as a machine gun. This configuration also eliminated the easy installation of the submachine gun paddle-type magazine release.

Pros: None. Cons: Cannot be converted to a submachine gun type, two-pin swing-down trigger housing; cannot use the trigger group in another HK firearm. Most parts in the trigger group will usually be modified semi-auto parts.

Dual Push Pin Registered Receivers

During the time that the HK conversions were being performed, there were few submachine gun parts available to use in the conversions, as a result many semiautomatic parts were modified to convert the firearm to function as a submachine gun. However, there were a few purist manufacturers around that would settle for nothing short of making their work as close to original as possible. They converted the semiautomatic receivers to accept original submachine gun “swing down” two-pin trigger housings by removing the lower attachment block for the semiautomatic type clip-on trigger housings, and altering the forward attachment point by installing a bushing to accept a front push-pin. The primary advantage to this arrangement is being able to attach a submachine gun trigger housing to the receiver; a secondary advantage is the ability to use standard submachine gun trigger group parts. HK 94 carbines that were originally converted to the dual push pin configuration are very desirable and demand a premium today. Although this was an ideal conversion method, it is now ILLEGAL to perform this alteration to any HK firearm.

Pros: The most desired conversion. Original submachine gun replacement parts can be used. Cons: Rare, the most desired and expensive type of conversion. It is no longer legal to convert existing clip-on receivers to the two-pin type.

Registered Trigger Packs

Instead of receivers, some manufacturers registered H&K trigger packs as machine guns. Some of these conversions will have a serial number engraved on the trigger housings. The disadvantage of registered trigger packs is that most of their housings are of the old pressed steel configuration. If the serial number is on the housing, they cannot be upgraded to the newer, and more desirable, plastic housings.

Registered Sears

Many manufacturers simply manufactured new sears, which could be fitted in to semiautomatic trigger packs, and registered them as machine guns. The sear itself will be engraved with a serial number. Common sears are Fleming, Qualified, S&H, and Ciener, but there are numerous others.

Pros: Registered trigger packs, and trigger packs with registered sears, can be moved into other HK firearms, including .223 and .308 models by changing the ejector. Cons: Moving the trigger pack out of an HK firearm with a barrel under 16-inches in length creates an illegal short barrel rifle. This requires that the owner register the short barreled rifle in order to continue switching the sear between firearms.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V16N2 (June 2012) |