By Mark White Photos By Dan Shea

In the design process for several years, and released just a few short months ago, Ruger’s new, rear-locking bolt gun is a carbine that the class II world has been waiting fifty years for. Very closely proportioned to Ruger’s popular 77/22, the rifle weigh only 6 pounds and is a compact 38 inches long. It has been said that the action is very similar to its little brother, chambered in .22 rimfire.

Background

Before we talk about the 77/44’s potential Class II role, it would be good to discuss the general characteristics of this finely proportioned carbine. In his middle years, Bill Ruger was a sportsman with fond and pleasant memories of time spent afield. As a designer he has an appreciation of small, trim, accurate carbines with enough pep to easily handle medium-sized game. His collective experience of hunting in Africa and America with the semi-auto, 44 Magnum carbine of the 1960s taught him that a 240 grain, .43 caliber slug moving along at a brisk 1,700 fps has penty of penetration and sectional density. It is a round with more lethality than its paper ballistics would seem to indicate.

As we shift forward in time to the 1970s, Ruger’s semi-auto .44 carbine became too costly to produce. It was dropped from production years ago. Shifting forward a little more, a number of atrocities (instigated by gun control zealots and perpetrated by weak-minded individuals who, curiously, seem to have had the same psychologist) have caused a number of countries to either restrict or totally ban semi-automatic (self-loading) firearms. Like it or not (and we really don’t) the day of the manually operated rifle is upon us. Seeing that trend, Sturm, Ruger & Co. is expanding its line of lever and bolt-action rifles with small magazine capacity.

Receiver

The 77/44RS is a traditional rifle with a number of innovative features. The receiver is an investment casting. It is cleverly shaped, machined, surface ground and heat-treated. The versatility of the casting process allows a number of components which have formerly been typically attachments (like the trigger group and scope mounting rail) to be integrally found. While some castings are often bulky, porous and brittle, Ruger’s investment castings tend to be carefully heat treated, strong and ductile. They sometimes allow for a modest amount of weight reduction.

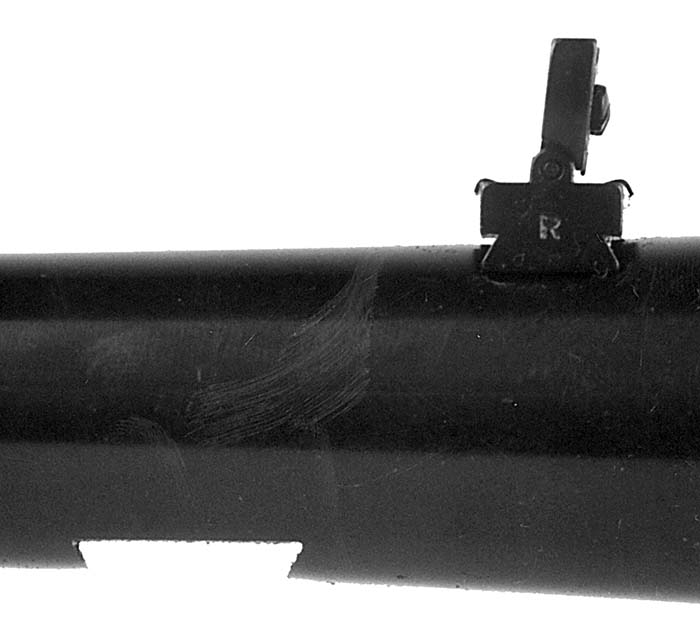

Barrel

The 18-1/2 inch barrel is hammer forged, and it is later turned to finish profile and dimension on a lathe. On the specimens we have examined there is a moderate dovetail slice taken out for the rear sight, a traditional but less than ideal way to mount the sight. In addition to that (and to our great surprise) another rather large dovetail slice has been taken out of the barrel where it is hidden inside the stock. Why this breach of integrity exists remains a mystery to us. If anything is sacred in this world, it is a barrel without dovetail slices and screw penetrations, as these tend to mess up harmonics and spoil inherent accuracy. While on the subject, Ruger has traditionally favored an 18 -1/2 inch carbine barrel for many of their rifles. In this case we feel that a rifled tube, a touch over 16 inches would deliver plenty of velocity, yet will reduce the carbine’s overall length by 2-1/2 inches a worthy goal. The factory barrel has rifling with a full right-hand turn in 20 inches, which is adequate for most .44 Magnum bullets driven to factory velocity. For longer, heavier bullets driven to subsonic velocities, a twist as fast as a turn in 10 inches would provide more stability.

Magazine, Trigger & Safety

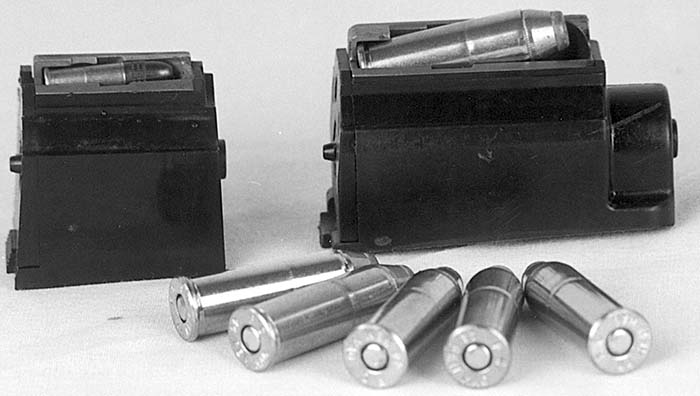

The standard 77/44 factory magazine is rotary, removable and holds 4 rounds. It is a very good magazine, feeds well, and I would expect that no trouble will come from it. The trigger is a bit stiff, but that is common and to be expected in this age of litigation. The trigger can be improved by careful stoning and buffing from a competent gunsmith. The lock time is fairly quick, at 3 milliseconds or less. Ruger’s standard bolt safety is proven, convenient and effective. Still, a rule that we lived by in Alaska is to never chamber a round until we were about to shoot. To this day, I will not hunt with a man who carries a round in his rifle’s chamber, and I don’t trust any safety.

Sights & Mounting System

The rifle comes equipped with iron sights which are adequate for young (but not old) eyes. It also comes with a set of low scope rings, which mount in two of three integral depressions molded into the top of the receiver. The factory rings are available for the standard 1-inch tube, and are so low that they only accommodate scopes of fairly low power with small objective lenses. Scopes with a 30mm barrel and/or larger objective lenses will require that another set of rings be ordered at increased cost from the factory. A tough, compact scope of about 4 power would be the appropriate choice for this weapon.

Stock

The standard stock is plain, checkered American black walnut, fitted with a rubber butt pad of medium density. The stock is traditional in appearance, well-formed, properly fitted and quite nice in proportion. It is neither too large nor too small for this trim, handy carbine. As an old stockmaker, I can find no area where material could either be added or removed.

Accuracy

The complete rifle functions quite well for its intended purpose. Most of the specimens we have examined will bench a 3-shot group of 2 to 2-1/2 inches at 100 yards. It must be remembered that this is a carbine, not a sniper rifle. Undoubtedly some rifles will shoot better than this, and some will shoot worse. This is a light rifle intended for carry in a canoe or in the woods.

The .44 Magnum is an adequate 100-yard cartridge. For the handloader, a cast lead, 300-grain, Keith-style bullet has a ballistic coefficient of .213. Starting at a comfortable 1,500 fps, it holds the record for penetration in ballistic gelatin. This bullet will retain a velocity of 1,240 fps at 100 yards, 1,100 fps at 200, 960 fps at 300, 890 fps at 400, and 826 fps at 500 yards. Once reaching subsonic velocity, the flat-nosed bullet loses very little additional velocity. Clearly, the .44 remains lethal at extreme range, but a rainbow-like trajectory makes a first round hit difficult much beyond 100 yards. The bullet will penetrate deeply and effectively at any reasonable range.

Suppressed Use

The first effective suppressed subsonic rifles produced in quantity were the famed British De Lisle carbines of World War II. These were made from reject Enfield rifles, reject .45 ACP submachine gun barrels, and 2-1/4” steel or aluminum tubing. Of varying quality, these rifles quietly drove 230 grain, .45 caliber bullets along at roughly 950 fps. Some were very accurate. Some were not. The most famous use of the De Lisle involved a small contingent of British commandos shooting into a convoy of Japanese soldiers. Shooting from a concealed position on a hillside, the commandos took turns, each shooting a single silenced round at a single soldier in the back of each truck as it drove by. This went on for hours, to the continued amazement of the Brits. For the period, the De Lisles were very effective suppressed carbines. They have been issued and used in many covert and overt engagements since World Ware II, and as recently as the war in the Falklands.

While silencer technology has improved greatly since World War II, the concept of driving a heavy, large caliber slug from a rifle at subsonic speed continues to intrigue. The most recent suitable host rifle has been the Remington 788. Occasionally chambered in .44 Magnum, these rifles were briefly available during the late 1960s, and were then dropped from production. While other repeating rifles have been available, most have tubular magazines that preclude the use of a suppressor. A bolt gun with a magazine beneath the action is the easiest to deal with. Conversions to .44 Magnum, .45 ACP and .45 Colt (the most desirable) have been made from time to time, but these tend to be costly and time consuming to build. They are also plagued with function problems, as they are typically cobbled from something else. Failures to feed, fire and extract are the rule, not the exception. Over the past 60 years a great variety of rifles has been tinkered with and suppressed, with very little success. Until now.

Ruger’s 77/44 finally brings a suppressable bolt-action rifle in a reasonable caliber to the table, where it can be used by police departments, animal control officers, drug interdiction groups, special operations people, and by qualified private citizens.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V2N2 (November 1998) |