By Mark White

In order to cope with the increasing violence in today’s world the law enforcement community continues in its search for more effective weapons and tactics. A recent study on the subject in the U.S. revealed an 87% miss rate with an officer’s duty sidearm in the heat of contact. Put another way, when an officer was forced to use his duty pistol in defense of life, 87% of the rounds expended under stress failed to strike the attacker.

Sequentially, the high miss rate causes two problems: 1. The unharmed perp remains free to continue his assault. 2. The rounds that missed may impact innocent bystanders, with severe painful, moral, emotional and legal ramifications.

For those who have been there, the emotional stress of being in combat causes peripheral awareness and fine motor control to vanish. For most, there is a significant difference between shooting at paper and shooting at a human being who represents a threat.

Before we get into the Ruger carbine, it might prove useful to look at a bit of history and precedent. Since the days of the U. S. Civil War (called the War Between the States in the south) it has been recognized that a firearm which is held and sighted like a rifle is inherently more accurate than a pistol. For those who desire specifics, a rifle is on the order of 16 times more accurate than a pistol. This is very apparent in the rough and tumble atmosphere of CQB. A rifle’s greater accuracy is due primarily to the way it is held and sighted, since barrel length (within reason) means little in terms of accuracy. A five or ten inch barrel is capable of delivering accuracy greater than or equal to barrels approaching 30 inches in length. With regard to power, a pistol cartridge is capable of developing most of its energy inside a five-inch barrel, and doubling barrel length will typically add a mere 10% to the velocity. Increasing its length to 18-inches, the legal minimum in Canada, will usually reduce velocity over that achieved with a five-inch barrel.

Some in the Civil War carried short carbines with barrels between 12 and 14 inches in length. In 1934 American legislators levied an (at the time) excessive $200 tax on carbines with barrels shorter than 16 inches. The result of this single action effectively stifled the development of truly compact carbines in the U.S.

Here we are, almost 70 years later, and our nation’s squad cars are primarily outfitted with pump action, 12 gauge shotguns. While I happen to like shotguns, they are often too much or too little. When used with slugs they may go through both sides of an automobile. They will penetrate quite a number of walls in an ordinary house, and are capable of easily killing innocents within. It is for this reason that shotgun slugs are rarely issued for urban duty.

When used with buckshot against an exposed, unarmored opponent under 30 yards a shotgun may be effective. At greater ranges, against body armor, against heavy or heavily clothed opponents, against a drugged individual, or behind tempered glass, buckshot is often ineffective.

In a recent attempt to stop a dangerous felon in a moving car trapped within a closed parking lot in Georgia, police officers discharged 17 rounds of 12 gauge buckshot from their duty shotguns at the suspect as he attempted to back over them repeatedly with a small car. The shots were primarily fired from the rear, and none of the 153 projectiles managed to penetrate the lightly built Japanese vehicle. Most of the pellets skipped over the rear windshield to impact the walls and windows of nearby apartments. Again, none of the projectiles penetrated the vehicle effectively. In fact, when the vehicle was finally restrained the suspect was totally unharmed (by gunfire).

In another recent shooting in a wealthy southeastern community, an intrusion alarm was activated when three thieves entered a large metal building. This happened during a shift change, so double the contingency of officers responded, with sirens blaring. Two perpetrators were apprehended quickly. The third, a large, heavy man, ran to a nearby wooded area. As the perimeter tightened the man charged a large group of the responding officers, yelling obscenities and firing a pistol at them as he ran. Big mistake. The officers returned fire with their duty shotguns, charged with buckshot. Those who visited the scene later mentioned that an outline of the suspect could be seen against one wall of the metal building, caused by those pellets that struck the sheet metal around the suspect.

While the buckshot ultimately stopped the suspect, it was only the large quantity of lead that brought him down. At a nearby hospital some 160 pellets were removed from the suspect, while 55 were allowed to remain. Surprisingly, the wounds were not fatal, and the perp later stood at trial for burglary and assault with a deadly weapon.

Both Glock and Ruger have maintained a police carbine in a major pistol caliber in the design and prototype stages for many years. It took events like the FBI/ Miami Shootout and the ’88 Palm Bay (Florida) shootings to get the enforcement community to realize that pistols and shotguns are often not effective against opponents armed with accurate carbines. It only takes a single round to end most armed confrontations, but that single round must be properly directed. Unlike the carbine, a single shot fired from a duty shotgun will direct either 9 or 11 pellets down range, and a sworn officer may be held legally accountable for each and every projectile in a court of law.

I credit Col. Jeff Cooper with reintroducing the concept of snap shooting with a carbine. With practice, the snap shot from a rifle or a carbine can be very fast. Experience tells us that a rifle shot will be considerably more accurate than a shot from a pistol.

For many years Marlin has produced their Camp Carbine in 9mm and .45 ACP. While the Marlin Camp Carbine is short and handy, Marlin neither officially recommends nor endorses it for enforcement use. It is a bit fragile, and those used by departments have not held up well to heavy use. Then too, there is the occasional problem of the hammer on a Marlin Camp Carbine riding back over the center of effort of its spring, sticking there, and rendering the weapon inoperable until it is field stripped. This is a major liability in a weapon intended for combat.

Ruger has been smarting for years over the “Barbarian” from Austria who (biblically speaking) stormed into the midst of the U.S. with an accurate, lightweight, reliable pistol, and captured the extensive law enforcement market in this country. Glock had the opportunity to introduce their carbine as a companion piece to their pistols, using magazines that were interchangeable. For some reason Glock decided not to do this. Ruger does have a modest share of the enforcement pistol market, and eventually took the plunge, using interchangeable magazines as a major selling point. The concept is a sound one, but the battle among 9mm, .40 S&W and .45 ACP clouds the waters.

While at the SHOT Show in Vegas a couple years ago I visited Ruger’s booth and again spoke with their law enforcement representative, as well as two of the people responsible for developing and testing the police carbine. Eventually a Ruger carbine was sent to me for testing and evaluation. I wanted it chambered in .40 S&W, but received the loaner carbine in 9mm instead. Oh well…

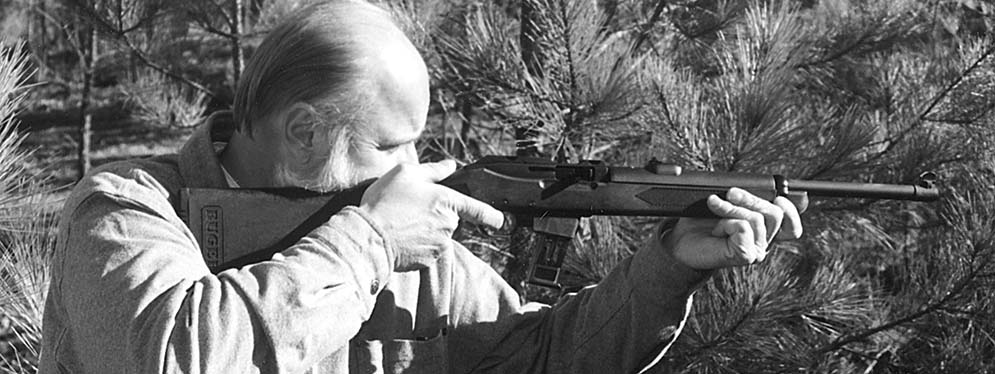

Getting the stats out of the way, Ruger’s Police Carbine is short, rugged and handy, measuring a scant 34.5-inches in overall length. It has a 16-inch barrel, which is a surprise to me, as most of Ruger’s other carbine barrels measure 18.5-inches, so they can be sold in Canada. The stock is molded in reinforced Zytel plastic, and has a soft, grippy molded rubber buttplate on the rear. The trigger is heavy and positive, breaking at roughly 9 pounds. This is a combat weapon, and we don’t want an officer accidentally putting a round through a wall under the heat of stress. I actually like the trigger as stiff as it is. One’s finger softens the break-jump when part of the trigger disappears into the cast-in-place trigger guard. The safety is of the sliding, cross-bolt type, positioned directly behind the trigger. It is accessible and positive.

The actual length of pull is slightly more than 13.7-inches. Jeff Cooper’s preferred length of pull is 12.5-inches for a rifle. A pull of close to 14-inches is a bit long, since most officers will be using the weapon while they are wearing body armor, and that will increase the pull even more. I would like to see the stock shortened another inch, or even a bit more, to accommodate a vest and to allow faster handling. I am six-feet tall, and carry a lightweight, five-pound, .308 carbine with a 12.5-inch pull when I am in Alaska. Anything longer snags on clothing—slowing rapid mounting of the stock to the shoulder.

Ruger’s carbine carries sights which are adequate for the purpose, but which have deficiencies. The normal rear sight is a straight notch in a blade, moderately protected by slight bulge in the plastic barrel cover. A rear peep or ghost ring sight was carefully researched and worked out during WW II. Such a sight is carried on the M1, M1 Carbine, M14 and M16. It is rugged, fast and accurate. It is my feeling that the ghost ring style of iron sight cannot be improved upon, and Ruger does currently offer the ghost ring sight as an option. Ruger’s front carbine sight is a straight blade, integrally cast between two small ears to protect it. It is my feeling that the ears should curl more to each side, to prevent someone from accidentally using one of the ears as a sight instead of the central blade, which could cause a miss in the heat of battle. While this may sound like an unbelievably dumb thing to do, I wouldn’t be mentioning it if it hadn’t already happened on more than one occasion. The front sight is fixed, and it is pinned into position on a step on the front of the barrel. All of the sight correction has to be handled by the adjustable rear sight, which appears to have been taken directly off Ruger’s MK II, .22 LR target pistol. The rear sight is a bit fragile, and could stand some beefing up.

A Zytel barrel cover is held at the front by Ruger’s traditional cast aluminum barrel band. The flimsy cover is held at the rear by a spring clip that fits over two heavy cuts in the barrel’s breech, considerably reducing the barrel’s thickness at this point. Curiously, the muzzle end of the barrel is quite thick, while the rear is weakened and made quite thin. The main heat and pressure are generated at the rear, where the barrel should be thick. The muzzle end could actually be reduced in diameter. Overall, the rear of the barrel should be thicker than what it presently is, while the muzzle end could be turned to a thinner diameter. This is precisely the reverse of the way it currently is. Once again, cosmetics won out over strength and utility. This is not good on a weapon that is purported to be a police carbine and intended to be used in a rugged combat environment.

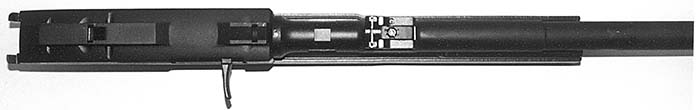

The cast steel receiver is an upper unit that houses an upper bolt. The upper bolt is connected by two heavy steel straps to a lower bolt that rides on a rod and a recoil spring in the forearm, bearing some similarity to the M1 Carbine and the Mini 14. Since this weapon is blowback operated, a considerable amount of weight reciprocates back and forth, divided more or less equally among the upper bolt, the connecting steel straps, and a lower bolt that rides on the rod beneath the barrel. It is a moderately efficient use of space, but not of weight. The sturdy stock weighs a little over two pounds, while the barrel and action weigh close to 4.5-pounds. When the weapon is loaded with a full magazine it weighs close to 8-pounds. Much of the considerable weight resides in the reciprocating mass of the bolt assembly.

The receiver hooks into a metal insert in the stock at the rear, and is held with a small screw through the bottom of the stock at the front. Slots in the top of the receiver will take the patented Ruger scope rings. I have known people who mounted a scope (and a suppressor in .40 S&W) on the police carbine, but a scope makes the weapon more fragile, and detracts from its use as a pistol-caliber carbine.

The weapon is fairly handy as it is, and is fairly accurate in rough-and-ready, offhand use. It will be considerably more accurate under combat conditions than a handgun. When put to use in a cruiser the carbine will either rest in a rack near the driving patrolman, or lie unused for months and rattle around in the trunk. The carbine has to be tough and reliable, and by-and-large, it is.

What would I change? First, the carbine is still too long for its intended use. I would cut at least an inch off the buttstock to reduce the pull, making it quicker and handier to shoulder. Then, I would shorten the fore end of the stock one-inch, and take six inches off the muzzle end of the barrel, finishing it at roughly ten-inches. That would then make the carbine an NFA weapon with an overall length of roughly 27-inches. By comparison, H&K’s excellent 9mm PDW (personal defense weapon) carries a six inch barrel, weighs about five pounds, and measures about 23-inches in length when its folding stock is deployed. While the PDW is an accurate weapon, I believe a modified Ruger Police Carbine would be even more accurate, as its stock is more rigid and more ergonomic.

I would thicken the Ruger stock in the wrist and action area. A plastic stock can be thick where necessary without paying a penalty in either material or weight, although the steel molding dies will have to be thickened to accommodate such a change. There are no sling swivels. While this weapon doesn’t need an ordinary sling, it does need some sort of carry or retention strap on its butt or grip, so an officer can hang or attach his weapon to his body while handcuffing suspects. Most departments have specific rules that mandate than an officer will never lay his weapon down while handling suspects. Those rules exist for a reason, and Ruger would do well to invest in a minimal strap retention system that works without being in the way.

If possible, I would reduce the reciprocating weight of the bolt to make the weapon a little lighter. I would then refine the front sight a bit, as mentioned earlier, and add a more rugged aperture sight to the receiver. And, of course, I would eliminate the nasty slices taken out of the barrel’s breech, thicken the rear portion of the barrel a bit, and taper the front slightly.

With intelligent refinement about two pounds could be taken from the barreled action, yielding a carbine that would be as accurate, yet lighter, shorter and handier. It would take a BATF Form 5 to transfer to a police department, yet these forms are free of charge and go through fairly quickly, supposedly within 20 days.

Both the barrel and the stock can be structurally considered as beams, and shortening will allow them to become automatically lighter, while retaining similar levels of strength. While a shorter 10-inch barrel will produce an energy level similar to a 16-inch barrel in a pistol cartridge, the strain on the bolt and buffer system will be lessened because the pressure curve will drop sooner. This may sound unreasonable, but we see it often when shortening barrels on blowback pistols and subguns. A cartridge doesn’t really release its hold on chamber walls until the pressure drops substantially. The heavier bullets found in .40 S&W and .45 ACP cartridges will increase the blowback effect over the relatively lighter 9mm bullets. A rubber buffer will be much lighter in weight, allowing at least a pound to be removed from the bolt.

In summary, in spite of its current shortcomings, I really do like Ruger’s police carbine. It is a sound concept that has been a long time in coming. It is still in an early stage of development and needs refinement. If the Mini-14 can weigh about the same, yet deliver over three times the energy, there is no reason why the police carbine can’t be refined to weigh considerably less than it currently does. Law enforcement has been slow to adopt the carbine. It hasn’t sold as well as it should have, and the weapon is now being released to the civilian market. Ruger has traditionally mandated that none of its NFA weapons will be released to Class III dealers. One result of this is that its compact 9mm subgun has sold poorly to police departments. Without dealers to aggressively hawk its wares few manufacturers will ever be able to sell niche products in a specialized industry. While Ruger continues to be the largest firearm manufacturer in the U.S., some of its products have been released without being fully refined and developed, and as a result have sold poorly. I hope that our comments are taken seriously, and that Ruger does refine its police carbine into a light, short, handy tactical weapon.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V3N10 (July 2000) |