By Rob Krott

I’ve been to South Africa twice – both times to make parachute jumps with the South African National Defense Force. On my last trip I visited the National Museum of Military History. Located in the Herman Ecksteen Park, Johannesburg, 22 Erlswold Way, in the northern Johannesburg suburb of Saxonwold, the Museum is adjacent to the Johannesburg Zoo and close to the Zoo Lake recreational area. It is easily accessible by road from the Pretoria-Witwatersrand-Vaal Triangle and a number of bus routes pass close by. Whadda deal: you can check out a great military museum and take the kids to the zoo.

Cannons, Tanks, and Airplanes, Oh My!

South Africa’s National Museum of Military History hosts a vast display of military weapons and uniforms. The museum’s extensive collection of flags, medals, decorations, insignia, war photos, paintings, steel helmets, rifles, hand grenades, edged weapons, and uniforms cover the full military history of South Africa including the First War of Independence, the Anglo-Boer War, the First World War, the Second World War, the Korean War and the South West African (Namibia) and Angolan conflicts. There is even a private collection of Jan Smuts’ medals and uniform items on display [Smuts was a talented Boer guerrilla leader, held a succession of cabinet posts, including defense minister, under President Louis Botha, and led South Africa’s successful WWI campaign in German East-Africa before becoming South Africa’s prime minister after the war.]

In addition to all of this is an extensive collection of artillery and armor, several aircraft, and even a German one-man submarine. The submarine, called the Molch (Salamander), is an 11-ton one-man boat. All electric and designed for coastal operations with a small range of 40 miles at 5 knots they look like a large torpedo. These boats were designed to travel submerged only and carried two torpedoes slung underneath. The first of 393 such boats was delivered on June 12, 1944, all the boats were built by A G Weser in Bremen. The Molch on display is #391. The Molch were used in the Mediterranean in a desperate action against the Allied invasion of the French Riviera coast. Twelve Molch were part of the K-Verband 411 flotilla and on the night of 25/26 September 1944 they attacked, sinking or damaging nothing for the loss of 10 out of the 12.

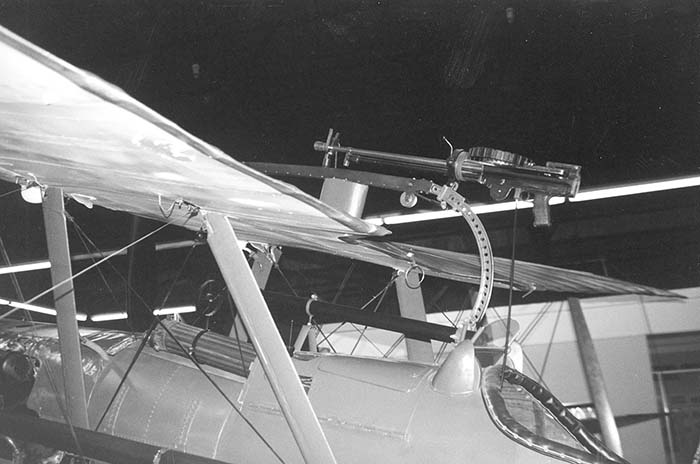

Bernie Mueller, a German pilot and close friend, was very pleased to see a ME-262 — the German Luftwaffe’s first operational jet fighter of World War II. It was fitted with radar as a night fighter. Also on display was an ME-BF 109 F-2/Tropical of the III Gruppe Jagdeschwader 72, captured at Marble Arch in the Libyan Desert by No. 7 Squadron SAAF in 1942. The aircraft displays also include another Messerschmit 109, a Focke Wolf 190, a Hawker Hurricane, a De Haviland Mosquito, a Supermarine Spitfire, a Dasault Mirage III, a De Haviland Buccanneer, a Tiger Moth, and planes from World War I — all in pristine condition. And ready to shoot them down is a 2cm Flugzeugabwehr Rahone (Flak) 30 gun.

The armor displays included a wide variety of tanks and armored vehicles. Particularly interesting was the Carro Leggero 3/35 Italian Light Tank. This two-man tank was developed from the British Carden-Lloyd series of ‘tankettes.’ It was bolted together with no rivets. Armament was twin 8mm machineguns — adequate for use against infantry in the WWI or against spear-carrying Abyssinian tribesmen, but useless for combat in World War II. The planes and tanks were all “cool,” but what I was here for was the small arms collection. And in that regard, the museum’s collection was definitely worth my ticket price. The development of South African small arms is traced from the early 1840’s using approximately 100 weapons on display including the first models of both the R1 and R4 assault rifles used by the South Africa armed forces.

Antique Arms

There were some great historical pieces here including several matchlocks, percussion lock muskets dating from the 1825 -1860 era, 1865-1875 era breechloaders, a Westley-Richards falling block carbine, a Swinburn’s Patent 1875 rifle, a modified Peabody-Martini caliber .450 rifle made by V & R Blakemore of London, a Colt Revolving Rifle from the 1850s, and something you’ll probably never see anywhere else: a Naval Model, seven-barrel volley gun, 2nd type circa 1787 handcrafted by Henry Nick. Only 655 of these “deck-clearers” were made for the British Admiralty.

The Boer War

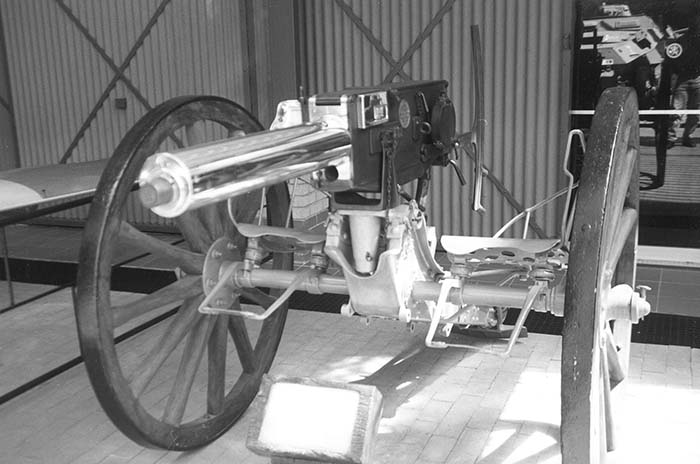

Prominent in the museum’s firearms collection were two weapons used extensively in the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902. In 1899, the British Army adopted the Maxim Automatic Machine Gun (later, variations were known as the Vickers). It was a water-cooled .303 caliber weapon with a rate of fire of 450 rounds per minute. When filled with water and loaded, it weighed about 70 pounds. A converted Maxim machine gun, firing a one-pound percussion-fused shell, was adopted for service by the Boers. Known as the “Pom Pom” (from the sound the gun made when firing) it was the first use of automatic light artillery in land warfare. The Pom-Pom was simply a large caliber, belt-fed machine gun firing explosive rounds. Relatively light caliber it “did little damage” but the sound of the gun and the shell burst tested the nerve of soldiers (it indicated more rounds still incoming). It was hard to locate on the battlefield as the smokeless ammunition (some of the first of its kind) produced little or no firing signature. Canvas belts held 25 brass-cased rounds carrying explosive charges with their percussion fuses. The first line of ammunition of 12 belts was transported in containers on a limber. First-hand accounts describe the Pom-Pom as being very effective; standard artillery, mostly, could still be avoided by quickly taking cover in the interval between the flash indicating the firing of the shell and its arrival. The Pom-Pom, on the other hand, could keep up a continuous stream of fire, to devastating effect. On display in front of the museum entrance is a German “Pom-Pom” surrendered to General L. Botha at Khorab, South West Africa, 19 July 1915. Markings (3.7cm Masch. K Nr. 543) identified it as a “Maxim” made by the “Deutsche Waffen und Munitions Fabriken, Berlin 1909.

The Boer War was definitely “the war of the rifle” as two very well known bolt-action, magazine fed military rifles made their combat debut during the conflict. The British Army, which had seen plenty of action against native tribesmen in Africa and the Near East, hadn’t faced a professional standing army since the Crimean War. But in the last days of the 19th century they squared off against a determined foe accustomed to the rigors of the bushveldt, fighting on their home ground, and armed with probably the finest rifle of its age… the Mauser M1896 7 x 57mm Carbine. The Mauser M1896 carbine used stripper clips making it much faster to load than the British Lee Metford rifles. It’s a lightweight and dependable weapon. The front sights are the standard pyramidal without guards and the rear is a V-shaped open sight. The rear sights could be adjusted from 400 to 1,000 meters (this was the age of long range massed rifle fires). I’ve been told that with the rifle set on 400 meters the round will strike about two feet high at 100 meters. The Boer Mauser was definitely not designed for snapshooting at close range. I think it would take some practice to hold low at near targets, especially if they were charging you and/or shooting at you. I would guess that the sights were modified or adjusted for use in the bushveldt. Several of these rifles are on display at the museum including a 7mm Mauser (1895) supplied to the Orange Free State and Transvaal made by Deutsche Waffen Munitionsfabriken, Berlin and Ludwig and Loewe & Co. The Ludwig & Loewe rifles are referred to as the Mauser Model 1896 but according to experts are actually 1895 Mausers. These weapons are in a display titled “Mausers and Mannlichers” and had this Boer quote on a placard: “United in the Fight for Freedom and Justice — God and the Mauser. Greetings from South Africa’s Battlefields”

While not equipped with the Mauser, the British had an excellent battle rifle as well. In 1887, the British Army issued the .303 Lee-Metford Mark I Rifle as a replacement for the .45 Martini Henry Mark III issued in 1871 and the .402 Enfield Martini Rifle issued in 1886. [The British Army had been slow to adopt the breach-loading designs being developed in Europe and America, though eventually by the time of the Zulu War of 1879 the standard issue rifle was the famed, breach-loaded, single- shot Martini Henry. The main problems with the Martini Henry were its weight, its length, and its single-shot action.] The Lee Metford was shorter, had a smaller bore, a bolt action, and a magazine holding eight rounds loaded separately. The Lee-Metford rifles used the turn-bolt action developed by James Paris Lee, a Scots-born American inventor, and the barrel and rifling designed by William Metford. Firing a relatively smaller cartridge than the .45 or .402 Martinis the Lee-Metford was a drastic change for the British Army at that time.

The Lee-Metford’s accompanying bayonet had a 12-inch blade and weighed 15 ounces and the rifle’s magazine held eight rounds; the .303 round then in use having a brass cartridge and being filled with 70 grains of fine black powder. In 1892, the Lee-Metford Mark I was issued and in 1898, the year prior to the Boer War, the Lee-Metford Mark II Rifle was issued to the British Army. The latter two rifles had cordite filled rounds. In 1900, the Lee-Enfield Magazine Rifle Mark I was produced. It had a detachable 10-round magazine box. It was made available for colonial troops fairly readily but as the British Army had been re-equipped with the Lee-Metford Mark II, the latter was the individual weapon for the British infantry soldier in South Africa. In 1897, the British cavalry were issued with the .303-inch Lee-Enfield Carbine Mark I. The carbine weighed 7 pounds 7 ounces against the 9 1/4 pounds of the Lee-Enfield Rifle; the rear sight was scaled to 2,000 yards against the 2,800 yards maximum range of the rifle. The .577/.450 inch Martini-Henry Mark I Rifle was also still in service and a nice example of this rifle is on display.

Meanwhile, in 1889 in Germany, the Mauser Rifle superseded the converted Mauser in use at that time. Weighing 9 pounds, 8 ounces, it was fitted with a 5-round magazine filled by pressing the rounds from a clip. On display was a good example of a Boer leather waistcoat with clip pockets — the “web gear” of the Boer War. With one of these functional garments on they could carry a good basic load of ammunition with ease. We’ve now come almost full circle with the usage of “combat assault vests.” Experience in the Boer War led Britain to adopt the European system for loading in bundles of five rounds. The Lee-Metford Mark II Rifle was converted to this system in 1902 and in the same year the Lee-Enfield Rifle using the same technique was issued.

The commando laws of the Boer Republics required all able-bodied males between 16 and 60 years of age to possess a rifle and the necessary ammunition. In 1888 General Piet Joubert, a Boer leader, decided Boer citizens were still inadequately armed, and the government began importing large numbers of Martini-Henry rifles that could be bought for four pounds sterling. In the three years prior to the outbreak of the war the Boer’s South African Republic (ZAR) known as the Transvaal, bought a total of more than 33,000 Martinis from the Birmingham firm of Westley-Richards. Throughout this period Boer burgher were still able to buy firearms privately, and this was why the Boers were armed with such a wide variety of weapons when the Boer War broke out. The 8mm Austrian Guedes rifle, similar in design to the Martini-Henry, was one of the last single shot rifles developed for a European power and were obsolete before they were delivered to Portugal as ordered. Portugal had already placed orders for the new M1886 Kropatschek repeating rifles before the Guedes were shipped. Seeing an opportunity, the Steyr factory sold the unwanted Guedes rifles to South Africa’s Boers. In total, 13,000 Guedes rifles were ordered in the two years prior to 1890. In 1893 General Joubert took a liking to the Guedes rifle, and an additional 5,305 of Guedes rifles were bought before the end of 1895. With the growing inevitability of war with Britain, the first few weeks of 1896 saw a frenzied search ensue throughout southern Africa for all available Guedes and Martini rifles. Eventually a further 2,200 Guedes rifles were acquired. The Norwegian Krag-Jorgensen rifle was brought to General Joubert’s attention around this time, receiving a favorable reception. But owing to supply difficulties only 300 of these were bought, along with 20 carbines. Also in 1896 the general’s attention was drawn to the model 1893 Spanish Mauser. This also found favor with the Transvaal forces and an order was placed for 20,000 Mauser rifles and 5,000 Mauser carbines. In the following year an additional 10,000 rifles and 2,000 carbines were ordered by the Boers. A total of 500 Mauser sporting rifles also were acquired in 1899, but a final order for 4,000 Mauser rifles could not be delivered owing to the British blockade of Laurenco Marques. One of the reasons for the size of these orders was the ability of the Berlin-based manufacturer to deliver.

Obviously, Boer small arms varied considerably. In addition to the aforementioned Mausers, Martini-Henrys, Guedes, and Krag-Jorgenson rifles a variety of personal hunting rifles and other weapons were employed as well. Boer forces also used shotguns; this is entirely likely, given that recruiters advised Boers to bring their own “…Rifle, ammunition, Horse, saddle and bridle, [and] food for eight days” to their mustering point. Throughout the war, of course, and especially during the guerilla phases where re-supply was no longer a possibility, many Boers took to using captured British weapons. Ammunition for these weapons could be stolen or captured, and although the weapons themselves were less than ideal, they were better than none at all. Weapons in the museum collection that were a long way from home included a Winchester ’76 .45-60, a Winchester 1895 box magazine rifle in .405, and a 30-40 Krag 1898 (Springfield Armory version). These weapons may have been used by the Boers or any of the American adventurers fighting alongside the British (the most famous of these was Major Frederick Russell Burnham, who was awarded the DSO while serving as chief of scouts for Baden-Powell.)

Other bolt-action rifles on display in the Johannesburg Museum include the relatively rare 6.5 mm Mauser-Vergueiro. Because southern Africa’s Union Defence Forces badly needed weapons during World War I the British bought 20,000 Model 1904 6.5 mm Mauser-Vergueiro rifles plus 12 million 6.5mm cartridges from Portugal. Portugal, while not of a mind to get itself involved in World War I, was certainly prepared to profit from it by selling these lackluster rifles to Great Britain. The British issued these Mausers to the First, Second, Third, and Fifth Mounted Brigades. They saw extensive service in the German South West Africa campaign. Hence both combatants were issued Mausers. The 6.5 mm Mauser-Vergueiro rifle, unlike the Lee Enfield, required considerable care in the field. It was not “soldier proof” and was withdrawn in 1909.

Boer War Machine Guns

The Boer War saw the widespread use of not only bolt-action magazine fed rifles but also belt-fed machine guns. Multi-barreled machine guns of the type invented by John Gatling in 1862 had become common in the years leading up to the Boer War, but by 1899 these cumbersome weapons had been replaced by single-barrel, belt-fed machine guns such as the Vickers-Maxim and the Colt-Browning Model 1895. As early as 1869 it was known that machine guns could duplicate or even exceed the effects of aimed volley rifle fire. At one test, held in Germany in 1869, a cumbersome Gatling gun showed better results over a minute of continuous firing at paper targets over 800 yards than a company of 100 riflemen firing aimed shots. Machine-guns, therefore, had become highly effective tools of war, and by 1899 their use had become common by most major world powers. Machine guns also multiplied the amount of firepower that a small force could bring to bear and excelled at sweeping open ground and laying down suppressive or harassing fire over trench lines. Their use in the Anglo-Boer War was to be both offensive and defensive.

Widely fielded by the Boers, the 8mm Schwarzlose MG M07/12 was invented by Andreas Wilhelm Schwarzlose of Charlottenberg Germany in 1902 and first produced by Steyr in Austria three years later. The Austro-Hungarian Empire used these guns in several models. In addition to being used in Austria it was used in 6.5 mm caliber in Sweden as the Model 14, in the Netherlands as the Models 08, 08/13, 08/15. Czechoslovakia used it in 7.92 mm and the Italians would later make great use of it, having large stocks they confiscated from the defeated Austrians after World War I. Another crew served weapon on display is a 37mm Maxim-Nordenfeldt MG (1885).

The museum has a very nice Maxim MK I (brass) used by the British Army, a Model 1895 Maxim [British] in .303, and a tripod mount MK IV designed for the Maxim. The Maxim was first used in Matabeleland (present day Zimbabwe) in 1893.

There is also a .303 Vickers/Maxim 1901 that was the forerunner of the famous Vickers machine gun of World Wars I and II. It weighs about sixty pounds (without water) compared to the thirty-four pound Vickers. Later modifications were minor, mostly to reduce the great weight. The bronze water jacket was replaced with a pressed steel jacket . This gun played a prominent part in the ‘civilizing’ of the British colonial empire. A famous bit of doggerel was “What ever happens/we have got/The Maxim gun/and they have not!” The Maxim was used on India’s northwest frontier during the Chitral Expedition of 1895, during the Sudan Campaign (1896), against the Matabele (1897), and again during the Boer War (1889 – 1902). It didn’t perform as well against the Boers (who used cover and concealment and employed open formations).

World War I

Visitors to the National Museum of Military History can learn about the causes, the various threats and campaigns and the results and consequences of World War I. An imaginative, life size reconstruction of a section of a typical trench and a description of life in the trenches is also included. On display here is a Lewis gun. The Lewis gun was the first successful light machine gun to be adopted and used in significant numbers. It was the standard South African light machine gun until 1940 when it was superseded by the Bren. The Lewis used either 47 round or 96 round detachable drum magazines and fired 550 rounds a minute. It was also used extensively in the aircraft role and at least one of the WWI aircraft in the museum mounts a Lewis gun. A Lewis gun aka “the Belgian Rattlesnake” was the LMG that, according to some accounts, Australian machinegunner Cedric Popkin used to shoot down the Red Baron. Gas-operated and air-cooled the Lewis gun is fed by a rotating drum containing either 47 or 97 rounds. The Lewis gun was initially designed by Samuel MacLean and was then developed and perfected by Isaac Newton Lewis of the US army. Unable to interest the US army in the weapon, Lewis took the gun to Belgium and set up a manufacturing company there in 1913. In 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, most of the staff fled to England where they were able to continue manufacturing the gun in the Birmingham Small Arms Company factory. The gun was subsequently used by the British, Belgian and Italian armies in great numbers, both as a ground weapon and as an aircraft gun. Though generally replaced by more modern weapons in the 1930’s, the Lewis gun was still in action during World War II. I have long been an admirer of the Lewis gun, but not until recently did I learn that the cooling jacket which makes it so readily recognizable is absolutely worthless, does nothing to cool the weapon, and merely adds 4 pounds of weight to this infantry weapon. Lewis, to prove his own “genius,” added the cooling jacket to the design he stole from MacLean.

World War II

Beginning in the late 19th century and ending 65 years later there are displays of seven Lee-Metford and ‘SMLE’ rifles that make for a nice comparison of the different variations and innovations, a good display of seven Mausers and Mannlichers (1886-1943) with bayonets, and another of seven Mausers (1871-1896). All these weapons figured greatly in South African history. There are four different anti-tank rifles covering the 1914-1945 period in the same display. This is the first I’ve seen the Mauser 13mm, the Maroszek 35 7.92mm, the PZB 38/39 7.92mm, and the Boys MK I .55 inch all together. A really fine comparision. There’s a pristine example second version of the FG-42 7.92mm — a weapon I’m always fond of examining.

For machineguns there are of course a Vickers .303 and for the Germans an MG42 and an MG 34, a tripod mounted “Lafette 34” with pads on front leg to reduce pressure on the carrier’s back. You can compare them to the horribly designed Italian 8mm Fiat- Revelli (mitragliatrice sistema revelli) that was prone to frequent stoppages (especially in north Africa) as the cartridges were oiled via a fluted chamber. The 8mm Breda Model 37 heavy machinegun however, also used oiled cartridges lubricated by an oil pump and its spent cartridges were re-inserted into a 20-round strip to allow recovery of empty cases. Unlike other Italian machine guns the Breda 37 was very reliable — large numbers were captured and used by the Allies and the German Army in Western Desert and Italian campaigns.

There is a comparative display of submachine guns and assault rifles (1940s-1950s) with magazines and cartridges that includes an MP-40, a STEN, an AUSTEN, an Owen, an M-3 “Grease Gun,” an MP-44, an AK-47, and an FN-FAL. The STEN, AUSTEN, and Owen, hang over top of each other in descending order so the 9mm sub guns with a common design heritage can be compared.

Other weapons from the era include US .30 M-1 Carbine, M-1Garand, M91/30 Russian (made in US), Russian Tokarev 40 7.62 mm rifle, and basically any WW2-European theatre military weapon I haven’t mentioned.

The Modern Era and “Integration”

Three South African small arms representing the adoption of foreign weapon designs over the last forty years include the R-1 7.62mm rifle, which is the South African version of the FN-FAL that entered South African service in the early 1960s; the.M-79 40mm grenade launcher (known in South Africa as a snotneus) which was adopted by the SADF in the early 1980s, and the UZI 9mm submachine gun (the Israelis weren’t squeamish about violating the arms embargo against South Africa.) Of course the most well known is the R-4 rifle, the South African produced copy of the Israeli Galil assault rifle. The standard general purpose machine gun in use by the SADF was the FN-MAG (mitrailleur a’ Gaz). The FN MAG combines the gas piston bolt mechanism of the BAR with the feed mechanism of the MG-42. There is a mannequin dressed as a member of the elite 32 Battalion – the SADF special operations unit formed from Angolans and other Africans. Clad in foreign camouflage he carries a captured AK-47.

One exhibit is marked “Umkhonto we-Sizwe (MK)” and a comment in the museum literature notes “Find out how and why the armed wing of the African National Congress came into being.” The ANC/MK were the indigenous insurgents during a long war of terrorism and guerrilla warfare against the SADF. We won’t get into details or personal opinions in this article, but for those interested in the history of the MK until its integration into the South African National Defence Force in 1994, there are some key exhibits: various weapons, landmines and hand grenades, insignia and medals, and the uniform worn by Joe Modise, the former Commander-in-Chief of Umkhonto We Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”) aka MK who became South Africa’s Minister of Defence in 1994.

Museum hours are 9:00am – 4:30pm every day except Christmas Day and Boxing Day. Admission fees are R5 per adult, R3 per pensioner, R2 per scholar. Meetings of the Military History Society are held at the Museum. The Military History Journal is produced in collaboration with the S.A. National Museum of Military History. The Museum complex also houses an Information Center. The Information Center holds the reference library archives (books, diaries, maps, periodicals, and oral histories, etc.) and the photo archives (stereographs, photos, films, and videos). The Information Center is open to the public and visiting scholars from 9am to 1pm and from 1:30pm to 4:30pm, Mondays to Fridays, except on public holidays.

SANMMH Contact Information:

Information Center,

The South African National Museum of Military History,

P.O. Box 52090,

Saxonwold 2132,

Johannesburg, Republic of South Africa

TEL: +27 (011) 646 5513 EXTS. 206,207,208,221

FAX: +27 (011) 646 5256

EMAIL: milmus@icon.co.za

Anyone interested in making a parachute jump with SANDF paratroopers (or other foreign militaries) should contact Rob via Military Parachuting Tours, Int. POB 1573, Olean, NY 14760; email: para6@hotmail.com

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V5N4 (January 2002) |