Shown against an original factory manual, the “Type E” Garand reflected Beretta’s innovative strategy to leverage the existing investment in M1 rifles. In Beretta’s thinking, this rifle offered a significant improvement in performance at a lesser cost than fielding a new battle rifle.

by Bill Ball

When poorer military rifles are made, you’ll find the Italians made them! So remarked a friend as he closed the bolt on a Carcano M1938 infantry rifle used by Mussolini’s infantry. This somewhat biased opinion would undergo significant revision when his hands wrapped around the Italian .30 M1 Garand rifles produced by Beretta or Breda, fully the equal of US .30 M1 rifles produced by Springfield Armory and Winchester. Had my skeptical friend taken the opportunity to hold and fire one of the rarest of the M1 variants, Beretta’s “Type E” Garand, frowns would turn to smiles.

By 1945, millions of Garands filled soldiers’ hands, rifle racks and armories across the world. Surviving World War II soldiers on both ends of the .30 M1 Garand documented some of the M1’s life-impacting lessons. Axis soldiers learned the tactical disadvantage of trying to outshoot a reliable 8-shot self-loading rifle with a 5-round bolt-action rifle of Mauser or Arisaka origin. Shouldering the 10-pound .30 M1 Garand in every theater of operation, allied soldiers learned it was quite heavy. In the South Pacific and facing mass Banzai charges, U.S. Marines quickly decided the ability to fire more than eight .30-06 rounds without reloading was a good lesson learned. While the rifle designed by John Garand fired eight rounds quickly and consecutively, recharging a partially expended clip proved nearly impossibly under battle conditions, and when finally expended, the eight round en-bloc clip ejected with a great deal of noise.

Following successful Allied landings in 1943, Italy left the German/Italian/Japanese Axis and joined the Allies as a co-belligerent. In a series of interesting political turns in the subsequent postwar years, Italy joined the NATO alliance, received large shipments of .30 M1 parts and machinery from the United States, and began to manufacture Garands at privately owned factories (Beretta) and state owned facilities (Breda). United States armories and technicians provided continuing technical assistance as the Italians gained expertise on .30 M1 rifle production and sales. Ultimately, thousands of Italian and Danish soldiers cleaned, shouldered and fired Beretta and Breda built .30-06 Garands.

The World War II lessons learned, and NATO’s adoption of the shorter 7.62x51mm cartridge, accelerated efforts to replace the .30 M1 with new battle rifle designs. The 1950s and 1960s saw the emergence of the FN FAL and Heckler & Koch G3, M14 (United States) and Beretta BM59 (Italy).

A new cartridge (and new rifles chambering it) changes a nation’s military capabilities. Advocates for change promise better reliability, performance and standardization – almost certainly leading to combat successes and reduced costs in the future years. The opposition reminds everyone change costs a lot of money, and the current inventory and infrastructure constitutes a significant investment. Every military establishment has staff officers whose primary job is to insistently raise questions about risk: “What happens if we go to war right in the middle of the transition?”

To field new ammunition calibers and rifles, the spare parts, technical documentation, repair and range facilities, individual proficiency, and tactical ability to effectively employ a rifle/cartridge combination most likely change as well. Modifying an existing weapons system could be a better decision than introducing a new one.

With millions of .30 M1 Garands as potential modification candidates, relative new M1 tooling and expertise available in Italy, a common new cartridge under adoption by NATO nations, and a recognized need for rifles to correct some of the lessons learned in World War II, the time seemed right to upgrade the Garand.

Against this backdrop, Beretta developed a proposal to modify the millions of existing M1s in different nations’ arsenals. Beretta’s strategy accommodated the adoption of the 7.62x51mm cartridge through simple and relatively inexpensive changes to existing M1 rifles.

Looking like a .30 M1 Garand with a big box magazine and new muzzle brake, the modified firearm was nomenclatured as the “Type E” or “E model” Garand in Beretta’s BM59 series of military rifles. BM59, by the way, stands for “Beretta Modification 1959,” a family of Beretta-produced rifles based on the .30 M1 Garand, with many similarities to the US M14 and M14E2 series of battle rifles.

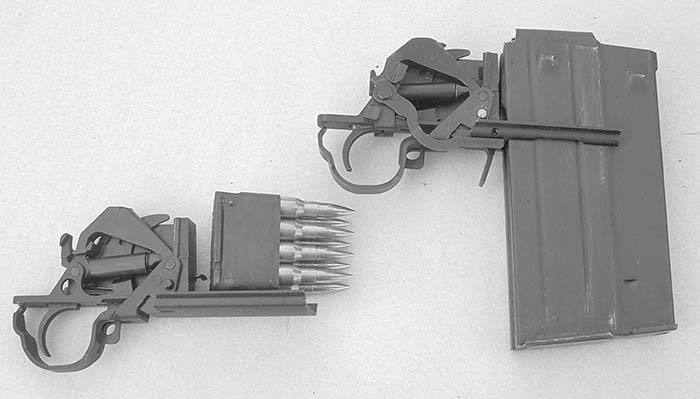

Beretta’s modifications did not reduce the M1’s combat loaded weight. A 20-round box magazine made the “Type E” Garand heavier, but greatly increased firepower without reloading. To fire 40 rounds from a loaded, unmodified M1 rifle, four reloading operations are needed. On the other hand, the “Type E” Garand user can fire 20 rounds without changing anything, and 40 rounds with just one magazine change. A new cartridge clip guide was fitted to the receiver so a partially expended 20-round steel magazine could be reloaded easily using stripper clips. While the typical “Type E” model was self-loading, the greater ammunition capacity proved useful as Beretta also offered the “Type E” Garand in a fully automatic version. The selector switch is discretely located on the left front of the receiver.

This capability, combined with recoil of the 7.62x51mm cartridge raised controllability questions. To address these concerns, Beretta workmen fitted new four-groove, right-hand rifled barrels chambered for the 7.62x51mm NATO cartridge, and added a unique muzzle brake, replacing the M1’s gas cylinder lock. Asymmetrical spacing and size of holes on the muzzle break brought the muzzle down and right, offsetting the normal muzzle rise in fully-auto fire. Compensating for a right-handed barrel twist, the muzzle brake directs gas flow with 24 ports on the right side; but only eight on the left side. From steel butt plate through the wooden front handguard to the muzzle, everything else on the “Type E” Garand retained the John C. Garand’s original design. The extra length of the muzzle brake increased the overall rifle length by over 1.5 inches to almost 45 inches.

Beretta did not produce a Garand magazine for .30-06 length cartridges – all of “Type E” Garands were chambered for the 7.62x51mm round. Incidentally, “Beretta “Type E” Garand and BM59 magazines are constructed from blued steel with an aluminum follower, and interchangeable between rifles. Magazines for US M14 rifles appear similar but will not interchange due to size and mounting differences.

Internet-based chat boards and .30 M1 Garand forums occasionally run messages from individuals seeking to wean the M1 away from the 8-round en bloc clip in favor of a large-capacity box magazine. Since the conversion to a box magazine involves machining the hardened M1 bolt and receiver, and subsequent re-heat treating, most qualified advisors do not recommend this conversion. However, when a major arms manufacturer like Beretta (with original production machinery, tons of spare parts, the Val Trompia production facilities, a heritage of nearly 500 years of gun making expertise, and the support of US armories and technicians) undertakes these modifications, then no questions about the quality, reliability and safety need be raised.

Questions raised by potential customers in various NATO and other nations turned instead to issues of cost, national pride, and desire for a different rifle than a modified M1. In Small Arms Today, author Edward Ezell reported that Argentina converted US-supplied M1s to use the 20-round box magazine. Argentina also purchased Beretta-produced BM59 rifles taking an identical magazine, so the possibility exists Beretta modified the Argentinean M1s into a “Type E” configuration. Additional research did not identify other national users of “Type E” Garands, suggesting Beretta’s “Type E” proposal, while technically sound, did not achieve wide scale acceptance. Ultimately, the FN FAL and the Heckler & Koch G3 rifles, along with the US M14 rifle, predominated among 7.62x51mm battle rifles, prior to the widespread acceptance of the 5.56x45mm cartridge in the late 1960s.

Overall, the “Type E” Garand conceived by Beretta retained many strengths of the underlying M1 design, but the modifications did not offer sufficient performance and cost advantages to edge out more modern, competitive offerings. Today, the only known source for “Type E” Garands is Reese Surplus in Geneseo, Illinois. Owner Bob Reese purchased the remaining “Type E” parts and much of the Beretta tooling in the 1980s. Today, Bob reports a few of the self-loading “Type E” rifles remain unsold.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V7N9 (June 2004) |