By Frank Iannamico

During World War II, the United States became allied with the Chinese Nationalists and provided massive military aid through the United States’ Lend Lease Program, enacted in March 1941, to assist them in fighting the Japanese army, which had invaded China in 1937. The Chinese were provided with military aid that included large amounts of U.S. weapons. Some of the U.S. submachine guns supplied were the UD-42, 1921, 1928 and M1-M1A1 Thompsons and M3-M3A1 “grease guns”. The wartime plan of the U.S. was to assist China in becoming a strong ally and a stabilizing force in Asia after the war.

The Chinese Nationalists and Chinese Communists had been fighting intermittently since 1927. The war represented an ideological split between the Western-supported Nationalist Party and the Soviet-supported Communist Party of China: the war was temporarily interrupted by the Japanese invasion. The Japanese, aware of the ongoing turmoil in China with the civil war, and territorial disputes between warlords, saw an ideal opportunity to dominate the country and secure its vast raw material reserves and other economic resources. When World War II ended with the Japanese surrender to the Allies in 1945, the Chinese civil war between the Communist and Nationalists intensified. Needing weapons to fight their Communist adversaries, many of the U.S. weapons supplied through Lend Lease were copied and manufactured locally in Nationalist Chinese workshops and factories; the quality of weapons varied from excellent to poor. The long, ongoing civil war eventually resulted in a Communist victory in 1949; the Nationalist government was forced from the mainland and settled on the island of Formosa (Taiwan) located off of the southeast coast of the mainland. Communist leader Mao Tse-tung renamed mainland China the Peoples Republic of China.

A Brief History of U.S. Submachine Guns

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, its military forces had few submachine guns in their inventories. Many decision makers in the armed forces of the day saw no real need for a submachine gun, there was no requirement for such a weapon that many felt only wasted ammunition. The collective results of the testing of the Thompson submachine gun by the Infantry Board, Cavalry Board and the Air Service during the 1920s were reported to the Sub-Committee on Automatic Weapons by Army Major O’Leary. The report summarized that: “From the foregoing recommendations and test reports, it is concluded that while the Thompson is a mechanically practical weapon, it offers no tactical advantage over weapons now available and should receive no further consideration or testing, the submachine gun being judged to have no military value at this time.” The Sub-Committee approved the recommendation. The early military testing and reports of the Thompson accurately reflects the mindset and tactics of the U.S. military in the post World War I era.

In 1931, the Infantry Board again evaluated the Thompson submachine gun. The Board concluded that the Thompson was only suitable for certain situations such as small wars against savages, jungle fighting, beach defense or riot duty. The Board went on to state that the weapon, “Has no place as a standard article of the Infantry.” The Infantry Board recommended that the Thompson not be adopted as standard, but limited issues of the weapon be authorized for special operations and riot duty. The United States Army eventually procured a small number of Thompson submachine guns for further evaluation and guard use. However, in 1932, the United States Army adopted the Thompson submachine gun as a “Nonessential Limited Procurement Item.” By 1938, the Model 1928 Thompson was upgraded to “Standard Procurement” for cavalry use in military vehicles. Although the U.S. Army was finally purchasing the Thompson they still viewed the weapon purely in a defensive role and not as an infantry weapon.

It was not until the U.S. became deeply involved in World War II would the value of the submachine as an effective military weapon be realized. The Thompson was designed over twenty-five years earlier during 1919-1920; it was heavy and expensive, costing as much as a .50 caliber machine gun. After it became apparent that the pistol caliber submachine gun had a role to play, the U.S. Ordnance Department began to look for a modern alternative to the labor-intensive Thompson.

During the Second World War, Germany fielded a number of new weapons produced from simple sheet metal stampings. The MP40 submachine gun started a world revolution in small arms design. The methods and materials used allowed weapons to be manufactured cheaply and very quickly in large numbers – very advantageous during a large scale war. Weapons manufactured by these methods proved as durable as their labor-intensive counterparts made primarily of milled steel. Some of the first designs fielded by the Allies were the 9mm British Sten and the Soviet PPSh41 and the PPS43.

Seeing the benefits of such a design, the United States Ordnance Department began to develop a similar submachine gun that was to be fabricated from inexpensive sheet metal. After an in-depth study by the Ordnance Department engineers, the requirements for a similar U.S. weapon were established. Development began by the Small Arms Development Branch of the Ordnance Department with assistance from the Inland Division of the General Motors Corporation. One of the first new submachine gun models to be designed was the T15 submachine gun. The T15 was a .45 caliber weapon that featured a straight open-bolt blow back operation commonly used in most submachine gun designs. The T15 quickly evolved into the simplified T20 model after several requirements were revised. One of the design changes was the elimination of semiautomatic function, and a requirement for the weapon to be easily converted to fire 9mm Parabellum ammunition. Because of the slow cyclic rate of the weapon it was decided that there was no need for a semiautomatic feature thus allowing the design to be further simplified.

The T20 had one very unique design feature that separated it from all other submachine guns of the day. On virtually all previous submachine gun designs, the bearing surfaces of the bolt would move forward and rearward supported by the inside surfaces of the receiver. On the T20 weapon, the bolt was designed with two horizontal holes that ran through the entire length of the bolt. The bolt then rode on two steel rods that were inserted into the holes, and were held in place by a steel plate oriented by two holes located in the rear of the receiver. Each guide rod had its own separate recoil spring. The steel guide rods were supported at the front by a steel guide plate that was indexed in the receiver by two integral tabs on the plate. A spring steel circular clip kept the bolt, guide rods and recoil spring assembly together until the barrel could be screwed onto the receiver. The front guide plate was secured to the receiver by the tightening of the barrel nut assembly. The primary advantage to the design was that the bolt never contacted the inside surfaces of the receiver. The unique arrangement made the T20 submachine gun nearly impervious to stoppages from dust, mud water or even sand. The T20 was one of the few weapons that were able to successfully pass the Ordnance Department’s rigorous mud and dust tests. In the design of the T20 the receiver was constructed by joining two separate stamped sheet metal pieces by welding. The receiver, the housing for the trigger and sear assembly, and pistol grip were all an integral part of a single assembly. The only other separate parts required were a dust cover/ejector housing for the trigger mechanism and a simple spring steel trigger guard that also held the cover in place. Other parts like the barrel bushing, sights, and ejection port cover were attached to the receiver assembly by rivets or welding – no threaded fasteners were used. The receiver of the M3 submachine gun was fabricated from sheets of .060-inch steel. Although several steps were involved, a new M3 could be made in 1.4 minutes!

The T20 was recommended for adoption as the Caliber .45 Submachine Gun, M3 on December 24, 1942. The contract for manufacture of the M3 was awarded to the Guide Lamp Division of General Motors. The Guide Lamp initial contract price for the manufacture of the U.S. M3 was $18.36 per unit. The only major part that was subcontracted out was the bolt assembly, which was manufactured by the Buffalo Arms Company of New York. The manufacture of the M3 submachine gun was further simplified with the introduction of the M3A1 model in 1945. One of the primary changes was the elimination of the troublesome cocking handle, replaced by simple depression in the bolt allowing the weapon to be cocked with the soldier’s finger. Other upgrades were introduced to simplify the disassembly of the weapon.

The Chinese Type-36 Submachine Gun

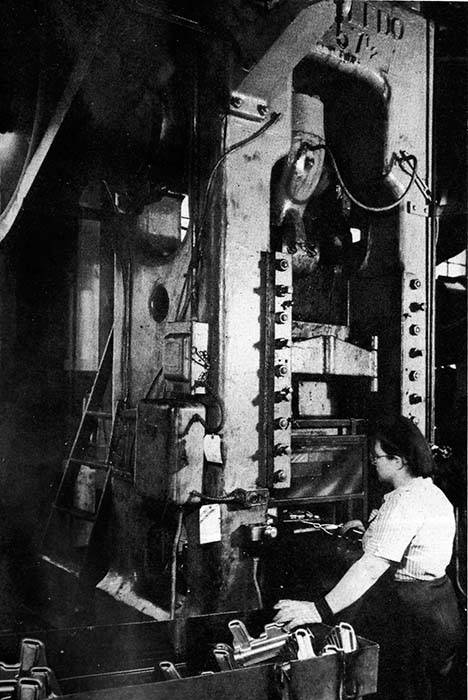

After the end of World War II and the U.S. Lend Lease Programs, the Chinese Nationalists and Communist Chinese began to copy and manufacture weapons of both U.S. and Russian designs. The U.S. submachine guns the Nationalists copied were the Thompson and the U.S. M3A1. Both of the U.S. weapons the Chinese chose to manufacture were relatively difficult designs to produce; the Thompson requiring a number of machine tools and skilled labor to manufacture. The M3A1, although a seemingly simple weapon, fabrication of the M3A1 receiver and parts would require special dies and large complex stamping machines. After stamping the M3A1 receiver halves, they needed to be accurately welded together without warping. Both U.S. weapons were difficult to manufacture with limited resources, especially when compared to the Soviet designs, the PPSh-41 and the PPS-43 submachine guns, whose receivers were simple U-shaped pieces of sheet metal which could be formed over a mandrel.

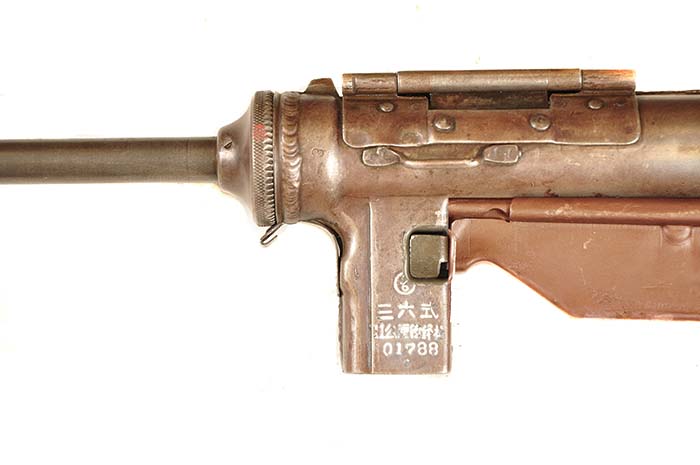

The first Chinese M3A1 clone produced on mainland China was adopted in 1947, and thus designated as the .45 caliber, Type-36. The designation came from the Chinese Republic calendar year that started in 1911 when the Republic of China was established by Sun Yat Sen. The Chinese .45 caliber Type-36, manufactured at the Shenyang 90th Arsenal, near Mukden, China was a near exact copy of the U.S. made M3A1, except the Type 36 used an M3 style barrel nut that had no flat areas for easy removal with a wrench, there was no oil container inside the pistol grip and the Chinese characters marked on the magazine housing. Reportedly fewer than 10,000 Type-36 submachine guns were produced before Communist forces overran the factory.

The Chinese manufactured Type-36 is more crudely constructed than its U.S. made counterpart. An attempt was made to swap parts between a U.S. made Guide Lamp M3A1 and a Chinese Type-36 and few of the parts were found to be readily interchangeable. The same problem was experienced with common parts from the Type-37.

The Chinese Type-37 Submachine Gun

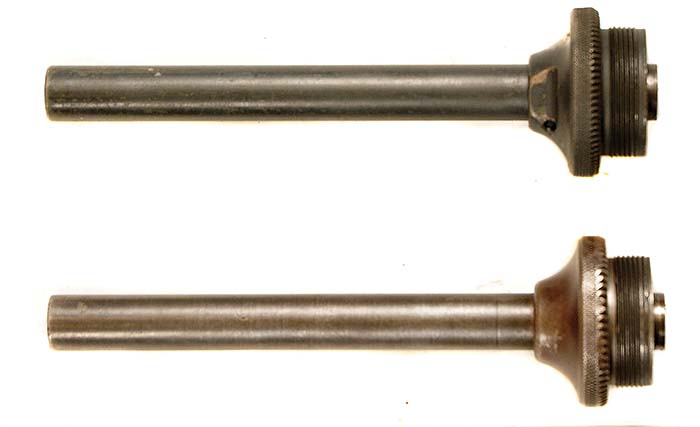

Like the Chinese Type-36, the Type-37 was also very close copy of the U.S. M3A1 submachine gun, except the Type-37 was chambered for the 9mm Parabellum cartridge. The 9mm Type-37 submachine gun differed only slightly from the Type-36, and was basically a conversion of the .45 caliber Type-36. The conversion parts are nearly identical to the U.S. made 9mm conversion kit for the M3 and M3A1. The Type-37 was manufactured at Mainland China’s 60th Jin Ling Arsenal located in the city of Nanking, China, then the capital city of the Nationalist Chinese. The Type-37 designation of the weapon indicates that it was adopted and manufactured during 1948. Prior to the Communist takeover of the Arsenal, the Nationalist Chinese fled to Formosa taking most of the manufacturing equipment with them. Once settled on Formosa, production of the 9mm Type-37 resumed and re-designated as the Type-39. The submachine guns manufactured on Formosa are marked with the logo of the new ordnance department established there, the Combined Service Forces. The M3A1 design was copied and manufactured in Argentina as the P.A.M. 1.

(Special thanks to: The United States Marine Corps National Museum, Triangle, Virginia, Mr. Al Houde and Bruce Allen, United States Marine Corps National Museum, Quantico, VA, Dolf Goldsmith, Nevada and National Archives II, College Park, MD)

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V16N4 (December 2012) |