The Colt SCAMP. Copyright © by Colt’s Manufacturing Co., LLC. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

by J David Truby

As the Beretta 92 replaced the venerable old Colt M1911A1 as the US military’s sidearm in 1985, few remember that it had been less than 15 years earlier that Colt built its better mouse trap, the handgun that almost succeeded its aging ancestor: the little-known Colt SCAMP, almost 40 years old now and barely known except to small arms cognoscenti.

Faced with the hoary age of the 1911A1 and its inevitable retirement by the military, Colt designers came up with a new concept in 1969. They decided not to merely replace the veteran pistol; they chose to improve the capability of an already good basic design. Colt design engineer Henry A. Into called his 1971 prototype the “SCAMP,” for Small Caliber Machine Pistol.

“We looked at all the mini-submachine guns already out there, e.g., Skorpion, Mini Uzi, plus the small Walther and Beretta designs, and, in addition our engineers tinkered with various pistols they converted to full-auto with large capacity magazines, like the Browning Hi Power. Then, we did several in-house designs, finally settling on the SCAMP as the one that met all the required criteria of lightweight, compact, easily hand-acquired, accurate and capable of putting out a high rate of effective suppressive fire,” said Ronald Stilwell, former president of Colt.

According to Henry. A. Into, former manager of handgun engineering for Colt, who actually designed it, the SCAMP was “more than just a handgun for individual military personnel. It was a solid, lightweight and accurate machine pistol…truly a versatile and useful offensive handgun, just a bit bigger than our 1911A1.

“Although we developed the SCAMP officially as a proprietary handgun for the military’s personal defense weapons program, what we turned out was a lot more. We gave the individual operator a whole lot of handheld firepower.”

Only slightly larger and heavier than the .45ACP 1911A1 pistol it was to replace, the SCAMP was built around a Colt-developed, high-velocity, centerfire .22 round. It was also far better balanced than the old Colt, according to Into.

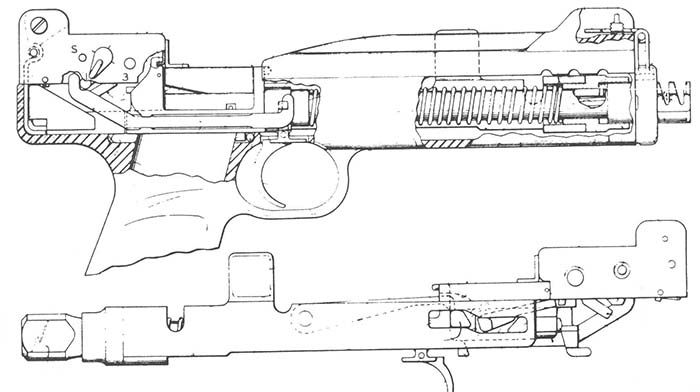

“The SCAMP was a gas-operated, locked-breech weapon with select-fire capability, including three-shot burst,” he added.

One of the major problems faced by any automatic weapon is the climb factor which draws the weapon off target. Light, miniature full autos like the SCAMP magnify this tendency. Eliminating that problem was a major accomplishment of the Colt engineering team, that sought minimal group dispersion in burst mode, according to Into, who also wrote Colt’s official proposal for the weapon to the military in 1971.

“Rather than build-in additional bulk and weight to control climb and recoil, we decided to create a compact compensator and a burst control mode, both of which would add to the inherent accuracy of the weapon by defeating the inaccuracies usually found in the smaller automatic weapons. The concept worked well,” he added.

Into added, “We used the burst control method because it is far easier for operators to keep their weapon under control that way, which also increases the potential for better aimed shots and a higher hit-per-shot ratio. This is especially true under stress situations, which is when this weapon would be used.”

The Colt prototype was 11.6 inches long, 1.4 inches wide and 6.8 inches in height. It weighed 3.25 pounds with a magazine capacity of 27 rounds. In a futuristic design, ahead of the times, the receiver housing was glass-reinforced, high impact plastic and contained the moving parts, all of which were made of stainless steel. The cylic-firing rate varied between 1,200 and 1,500 rpm

Another factor in the control and accuracy problem was that the cartridge originally suggested for the SCAMP was the .223 round, far too hot for an ordinary handgun, much less a machine pistol.

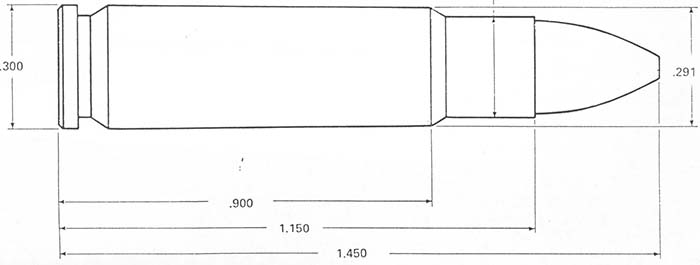

The SCAMP’s .22-centerfire cartridge fired a 40-grain bullet at a muzzle velocity of 2,100 fps. Colt officials developed the round specifically for the new weapon. The world standard and popular 9mm round was rejected because of its relatively heavy recoil signature. The designers also rejected the rimfire .22 long rifle because of its inadequate ballistics.

Into’s later research rejected the .22 Winchester Magnum and the 5mm Remington cartridges. The .22 Hornet cartridge was studied for modification, as well. However, the Remington .221 Fireball cartridge was used as the starting point for the new Colt cartridge. In their benchmark book on submachine guns , Nelson and Musgrave explain the design capability of the new Colt cartridge, writing, “Should a substantially different type of ammunition than ball be desired, the general design is capable of further modification…a multiple flechette round, for example.”

Testing showed that the new round shot flat and accurate out to about 125 meters, far superior to most military pistols, plus it had the full-auto and burst control capability of the SCAMP pushing it. By the way, this .22-centerfire Colt round developed for the SCAMP was later redesigned as a rimmed cartridge for revolvers, to be used primarily by security forces. This effort met with about the same level of contractual success as the original SCAMP design.

The SCAMP’s grip design was fashioned after the thumb-rest grips of target pistols and the bore was located low to the firer’s hand with the firing mechanism above the bore to lower the center of gravity and improve balance.

The sights were open partridge, adjustable for windage on the front, plus rear sights with ear protectors and windage adjustment. According to Into, “We also designed a quick-point aiming rib into the housing design for combat shooting, plus the weapon was balanced for natural pointing characteristic along the shooter’s forearm.”

Fieldstripping was simple and required no tools. A major part of Into’s design requirement was “for simple maintenance and a high degree of insensitivity to environmental harshness,” he explained.

The SCAMP was designed for performance under poor environmental conditions and with ease in maintenance. Into noted, “Face it, we do not fight wars in hospitable locales and you want a survival weapon that’s going to work each time and every time, no matter the field conditions.”

Thus, all metal parts were built of stainless steel, while the housing was fabricated from fiberglass-reinforced plastic. The front sight was anodized aluminum. Field stripping was designed to be easy and is component based so as not to lose small parts in the field. Colt also proposed several ways of storing and carrying the weapon; including two new holster designs and a Velcro-based hook and loop fastener for wear on the uniform. This design was offered for aircrew use.

Although only one prototype SCAMP was built, it was tested both by Colt and military officials. According to Into, “We were highly pleased with the operation and performance of the weapon…it was all we had hoped it would be.”

The Army said it had evaluated the weapon only on an unofficial basis and one ordnance NCO with whom I spoke said he shot it at the factory. Retired M/Sgt Fred White had been at the Army’s Rock Island Arsenal facility after two tours in Vietnam and was at Colt to do some work on what eventually became the M16A2.

“They asked me to try this experimental pistol back in 1974, said it was one of a kind,” M/Sgt White explained. “I recognized it was bigger than the old Colt auto, but the old one didn’t have three-round burst or the flat accuracy this gun had. I liked it a lot. Show me any other solid, working machine pistol that was smaller than 12 inches and weighed 3 pounds. That one was it, too bad it didn’t cut the grade.”

Of course, part of the original design thought for the SCAMP was as a survival gun for the Air Force.

According to Robert Ormann, who was with the USAF developmental command at the time, one of the Air Commando people had seen the SCAMP at the Colt plant and tried to interest his service in a modified version of it. Ormann says, “We were looking for a personal defense weapon that was fast, accurate and small enough to stow in the tight confines of our aircraft. We looked at the Colt design, but, only unofficially; there were no trials or other tests that I know of.

“As I recall, it looked somewhat like that later Steyr TMP with that grip magazine and the low-mount compensated barrel. The one we had had an 18-round magazine and fired a bottlenecked .22-centerfire cartridge. It was a fairly high velocity round, compared to the .38, 9mm and .45 pistols our people had in those days.”

He says the SCAMP shown to the air force personnel was in competition with the design known as the Davis Gun, after Dale M. Davis of the USAF Armament Laboratory at Eglin AFB. The Davis Gun, which rested along the firer’s arm, rather than a traditional stock, later evolved into the Bushmaster design, which was subsequently developed into a series of military and civilian firearms. Ironically, too, Colt’s designers developed their own version of an arm gun known as the Lightweight Rifle/Submachine Gun, known as the IMP because it used the .221 IMP cartridge.

Unhappily, though, for Colt, M/Sgt White, and the USAF, the official military line was that the SCAMP was not the answer to that better “man trap” handgun they had been trying to build since 1911. Thus, the SCAMP project did not evolve beyond the original prototype, so that no cost estimates were even generated.

Happily for ordnance historians, though, veteran Colt engineer, Ed Zalewa kept track of that SCAMP prototype, insuring its safekeeping in the company’s archive vault. He told me, “the firearms industry is not real good about retaining historical records and valuable prototypes. We are in our department, and that is why you can see this one-of-its-kind SCAMP today.”

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V7N8 (May 2004) |