By Jason Wong

The Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence, located in the Shau Kei Wan district of Hong Kong, depicts more than 600 years of Hong Kong military history. Originally designed as the Lei Yue Mun Fort, the museum depicts the history of the Opium Wars, the life of British conscripts, World War II, and the hand-over of Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China within the 34,200 square meter fort.

With its strategic harbor, the tactical value of Hong Kong was recognized by the Chinese emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties. In 1394, two battalions were established in Hong Kong to protect the burgeoning local trade. As a major port of trade, Chinese warships based from Hong Kong island patrolled the South China Sea to protect trade and commerce from pirates, foreign invasion, and Western influence. Examples of Chinese warships used during the period were on display at the museum, complete with salvaged examples of Chinese manufactured cannons. With a bore of 8.3 centimeters, (3.27 inches) the cannons were capable of firing a projectile weighing 1.4 kilograms (approximately 3 pounds). Later cannons were purchased from Portugal and Holland through European missionaries in the area. By the late Ming Dynasty, the coast surrounding Hong Kong was well defended. Hong Kong played a major role in the Opium Wars (1839 – 1842) between the British East India Company and the Qing Dynasty. Although opium was outlawed in Britain, opium was manufactured under British monopoly in India. The British East India Company forcibly sold opium to the Chinese populace, leading to the Opium Wars of 1839 and 1842, when Qing dynasty emperors outlawed and confiscated opium being sold illegally. On display within the museum are captured strong boxes used to transport opium, Qing Dynasty cotton and bronze based armor, and paraphenilia used to smoke opium.

The resultant defeat of the Qing Dynasty in the Opium Wars lead to the cessession of Hong Kong from China to Britain in August, 1842 via the Treaty of Nanjing. Faced with possible attacks from France and Russia, the British decided to construct a number of batteries south of the main channel leading to Hong Kong. Designed by the Royal Engineers in 1880 to defend Victoria Harbor, the Lei Mun Fort was deemed the most sophisticated coastal fort of its time.

Originally comprised of 7,000 square meters, the fort consisted of eighteen armored casemates, constructed to function as barrack rooms, magazines, and storerooms. Once constructed, the structure was covered and concealed with dirt within the coast of the island. Construction was largely completed by 1887, allowing the fort to occupy a strategic position guarding the eastern approach to Victoria Harbor.

The fort was initially armed with two 6-inch Mk.IV breech loading cannons mounted on disappearing carriages. With a range of 8,200 meters (26,900 feet, or more than 5 miles), the guns at Lei Mun could defend the entire seaward approach to Hong Kong and Victoria Harbor.

Concealed in an earthen emplacement, the Mk. IV guns were hidden until ready to be fired. The guns were then raised into position and fired, with the force of the recoil driving the guns back below the earthen emplacement and out of visual line of sight. In this manner, it was very difficult for a warship to place accurate and aimed fire upon the battery.

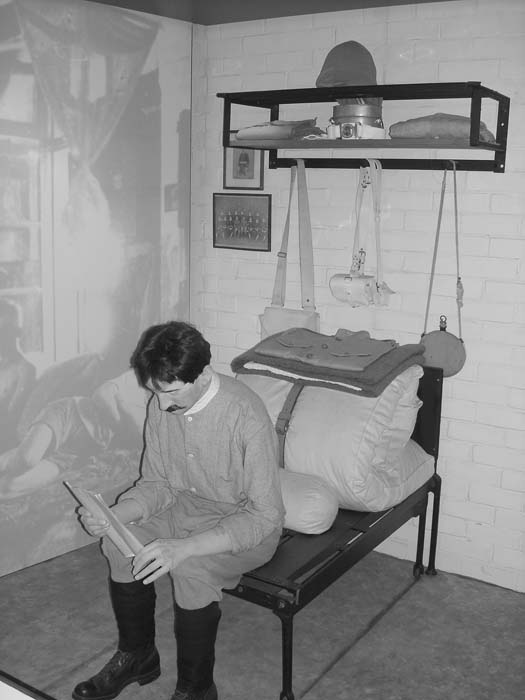

Faced with a period of relative peace, the British soldiers assigned to Hong Kong endured a long and monotnous duty assignment. Flogging for minor misdemeanors had been abolished in the late 1800’s. Medical facilities, food, and accomidatons were improving, but were far from luxurious. Technological advances were leading to more sophisticated weaponry. Nevertheless, tropical diseases were rampant, and foreign service meant a prolonged period of absence from home. Being so far from home with boredom and an endless routine, led many soldiers to drink as a means of escape.

Barracks were simple, and remarkably similar to other British outposts around the world. Sharing a room with 30 other soldiers, the typical British soldier had a bed and a shelf to store his personal belongings. During the day, the bed would separate into two parts allowing one half to be stowed underneath allowing more space within the barracks during off-duty hours. Inspections of uniforms and equipment were conducted daily for cleanliness, completeness, and precise arrangement resulting in an orderly, if not austere, living conditions.

The fort continued in active service to the British monarchy until World War II. On 8 December 1941, the Japanese launched their attacks on Hong Kong. Following the capture of Kowloon and the surrounding area, the British Forces immediately strengthened the defenses at Lei Yue Mun to repel and prevent the Japanese from attacking Hong Kong. Although the British defense forces managed to repulse several raids by the Japanese, the British were overwhelmed on December 19, 1941, and the fort fell into the hands of the Japanese military. Following World War II, the fort bore no military significance in the post-war period, and was utilized as a training site for the British Forces until 1987 when it was finally vacated.

In view of its historical significance to Hong Kong history, the fort was developed into a museum, and opened to the public on July 25, 2000. Located at 175 Tung Hei Road, in the Shau Kei Wan district of Hong Kong, the museum is easily accessible by public transportation. The museum is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. every day except Thursday. Admission is HK$10 for adults and HK$5 for students, handicapped and senior citizens. Admission is free on Wednesdays.

To get to the museum via public transportation, take the Red subway line to the Shau Kei Wan Station. Exit the station via the B2 exit, and follow signs for the museum. The museum is an easy 10-15 minute walk from the subway station.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V12N3 (December 2008) |