By Dan Shea

A village near Bangkok, Thailand, 11 November, 2007: SAR caught up with the intriguing and somewhat elusive Dr. Dater as he was making a pilgrimage to the site of the original Bridge over the River Kwai in Thailand (Doc Dater is a rail enthusiast as well as a military historian.) We joined him in an unsuccessful search for a mutual old friend, Don Walsh of 1970-80s clandestine weapons manufacturing fame. Don had left the US and joined the Thai Ex-Pat community in the 1980s, and Dr. Dater and I had discussed a reunion of sorts since we were both in SEA on defense related projects. Neither of us had contact with Don in a long time, and unfortunately, we did not find Don and that will have to wait for another day. We did manage to sit Dr. Dater down for a cheap glass of local white wine and the most in-depth interview ever done with a man who is considered by many to be one of the most innovative and perhaps the most copied suppressor designers of the last half century. – Dan

Dr. Philip H. Dater was born in the latter part of April, 1937 on Manhattan Island in New York City. He has two brothers, Tom and Sheldon, and a sister Emilie. Dr. Dater has two daughters from his first marriage, Diana and Valerie, and one daughter Julie with his wife, Jane, whom he has been happily married to for over thirty years. He is one of the brains behind Gemtech, and his private consulting practice with Antares Technologies has done a lot behind the scenes for the modern small arms community.

SAR: Phil, you were born right in the middle of the Great Depression, and started school just before World War Two.

Dater: That’s correct. I went to grade school in New York City, and when I was 13, we “escaped.” My mom moved to Kentucky, and I went to a military school for a year. The family moved to Wichita, Kansas, where my mom remarried, and I went to Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire for a couple years. I graduated from Wichita High School East. I went to the University of Kansas for two years, followed by the University of Wichita for two more. My major for three years was mechanical engineering. Then I switched to pre-med and went to McNeese State College in Lake Charles, Louisiana, for three years, graduated from there, and then went to Tulane University School of Medicine for my M.D. degree.

SAR: Those are two recurring themes in your life, mechanical engineering and medicine. What about firearms?

Dater: Clearly the mechanical interest drove me into firearms, like it leads some to cars or other machines. My first handgun was a German Luger; I paid $15 for it from a store in Exeter, New Hampshire. I was 14 years old.

SAR: You were able to walk into a gun store in 1951, at 14 years old, and buy a handgun?

Dater: Of course. That was perfectly normal. There were no restrictions on it. No problems in society from it either.

SAR: When did your interest in automatic weapons come in?

Dater: I got my first exposure to real full auto when I was about 15. One of my classmates at Exeter lived in upstate New Hampshire, and he had a Russian PPSh-41. We’d occasionally go up to his place for the weekend and shoot that, and his 45-70 lever action. That was 1952. No one knew there was an issue about registration, so I don’t know if it was registered or not.

SAR: When did you get your first automatic weapon?

Dater: I purchased an M1 Thompson in 1955, when I was a student at the University of Kansas. Over the next couple years, until probably mid-1957, I ended up purchasing approximately 14 automatic weapons. I had a 1918A2 BAR, an M2 carbine and a Sten MK II. I also had an FG42 that I bought from a police officer. I don’t remember if it was a first or second model. None of it was in the Registry, we really didn’t know about the registration being needed. You could buy them fairly easily at gun shows. I bought my Thompson from a private individual in Kansas. We had been chatting, and I had expressed an interest in machine guns, and one of my friends there said, “Oh, my uncle has a Thompson, and he’s not interested in keeping it.” And I said, “Well, I’d sure like to buy the thing.” I paid $75 for it.

SAR: You didn’t even know what the National Firearms Act was?

Dater: No, I did not know what it was at the time. It was easy to find machine guns. Most salespeople at gun stores would provide contact information, and you could find them at almost any gun show – there weren’t many shows then, either. A lot of veterans had brought guns home and they were considered alright by everyone I met. There was no big deal about it; nobody was really concerned about it. Nobody cared. In fact, when I first moved to Louisiana, I lived for the first year in a little town called Oberlin, which is about 50 miles north of Lake Charles. The sheriff of the Parish and I would go out together, and we’d shoot turtles with machine guns. He’d take his department’s Reising M50 out and I’d take my Thompson or my Reising. We could buy surplus GI 45 ACP ammo for about a penny a round. It was cheaper than .22 long rifle, and we’d go out and shoot turtles. He never mentioned any machine gun registration. The captain of that district of the state police had his own 1928 Thompson, and he’d come out shooting with us. In fact, I would clean his Thompson. At one point, his gun wasn’t working, and I just swapped firing pins out of my M1 Thompson with it. They all had personal machine guns, no one ever mentioned anything about a “Registry” so we just bought and sold them like regular firearms. Eventually, these were taken from me. A friend of mine I’d done some trading with heard about this need to register machine guns, so he wanted to register everything, and he went to a local police department in another town in southern Louisiana to find out about it. The police department called the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax Unit from the IRS to find out how to go ahead and register this guy’s collection, because they didn’t know either. This guy had Maxims and everything else. The agent from the ATTU came out and confiscated his entire collection. One of the things they asked is, “Well, where did you get this, and where did you get that?” They were interested primarily in whoever had stolen some originally from the US government or if someone originally imported it illegally. A number of machine guns that we had were converted from what were then called “Dewats” (Deactivated War Trophies), which in those days were pretty easy to buy and sell, and to reactivate. Dewats didn’t require registration in those days. The Reising that I had was originally a Model 60, and I had built the complete conversion on it to a Model 50 Reising. The agent came and knocked on my door, I was 20 years old at the time. (Of course, in those days, the age of majority was 21). He just came in and said, “I’m here about some machine guns, we just picked up your friend, and he had done some trading with you. I need to see what you have and where it came from.” Then, they took my machine guns away.

SAR: Let me recap that. It was over 50 years ago, and nobody really was paying attention to any requirement for registration, none of the police departments knew anything, many actually had their own unregistered weapons personally, and they went out shooting with non-LE. As soon as your friend found out about it and went in to register, the government came out and confiscated his firearms collection then hunted down everyone he knew?

Dater: Exactly. I didn’t really know that they were illegal for private ownership, or that there was such a thing as a Registry or National Firearms Act until the agent paid me a visit from ATTU in 1957. It was in 1968 that Congress recognized that so many guns were not registered in the NFRTR that with the new laws they had to have an Amnesty and publicize the registration requirement. At that point in1957 though, I realized that there was a serious issue about machine guns. I learned more about it, and in the early Sixties when I wanted a Sten, I wanted a Dewat because there was no big deal on it, no registration needed. I bought one from a guy up in Wisconsin, mail order, he had advertised in Shotgun News. It came with some registration papers. I called him and said, “What is this?” He said, “Oh, registration is voluntary on Dewats.” Of course, that turned out to be a valuable asset when 1968 came and went. The first registered working machine gun that I bought was in 1976, and it was the little Military Armament Corporation Ingram M11 in .380. I’d just seen the movie, “McQ,” and I went into a local sporting goods store and said, “Boy, I just saw a neat movie with a neat little machine gun. Are there any dealers in town?” The guy in the sporting goods store, sort of almost like back in the ’50s, he says, “Yeah, go see Sid McQueen at S&S Arms,” and gave me the address. I went over to Sid’s, and he had about a half dozen of these and a bunch of other things hanging on the wall. And I thought, “Gee, that is cute,” because it was so tiny. I bought it, and I bought the silencer to go with it. The Form 4 took a whole three weeks to go through. Anything that went over three weeks, everyone started to get really antsy about. The funny thing was at that point in time, when the paperwork was in on that, I got a call from ATF. This is, again, in ’76. They said, “Are you the same Philip Dater who used to live in New Orleans and had a registered Dewat Sten? Did you know that you were supposed to notify us when you moved?” And I said, “No, I didn’t know that.” They said, “Well, we’ll take care of it, we’ll amend the Registry to show that.” I said, “You know, I don’t even remember where the paperwork is on that Sten,” and they said, “Well, we’ll send you a copy of it,” and they did. They were very helpful in those days.

SAR: You mentioned that you bought a suppressor in 1976 from Sid McQueen, but that was certainly not your first experience with firearm suppressors.

Dater: I had fired an original Maxim .22 suppressor on a rifle in .22WRF caliber, and had been involved with Amateur Radio since 1950. Hiram Percy Maxim, Sr. was the Father of Amateur Radio you know, as well as inventor of the Maxim Silencer, so I was familiar with his work. It was 1958 for my first crude design though. While I knew there was registration of machine guns, nothing had been said about silencers. I had a problem with some neighborhood critters when I was living in Lake Charles, Louisiana. The first suppressor I made went on a .22 Mossberg rifle that I had. I was looking for some way to couple the suppressor to the gun. I thought of the Rayovac flashlight that had a nice big head, and Thermos made a nice big cork that was about the right size to replace the lens and the bulb. I used an old Rayovac flashlight, and for packing material on it, I used corrugated cardboard. I carefully punched out with a paper punch some quarter inch holes, and then with scissors, I cut around an outline that would just fit into the flashlight body. I made that suppressor out of an old flashlight and a whole bunch of corrugated cardboard disks. Some were smaller than others, so this might be considered “wiped”. I certainly didn’t invent “wipe” suppressors, the Welrod and some others were before then.

SAR: So your first suppressor design was over fifty years ago? What was your second design?

Dater: The second design was actually a little more sophisticated. It was made out of some brass tubing for a drain pipe for a sink, and soldered in a mount with some threads on it. Actually, the first one didn’t have usable threads, it just had a hole and a couple of set screws to hold it in. I made a little cage that supported some fiberglass insulation. It was sort of along the lines of a glass pack muffler. That was probably about ’62. I was in medical school at the time, and there was a streetlight outside of our apartment that was a real irritant, shined in at night.

SAR: So you had to attend to that streetlight.

Dater: That’s exactly what I did. That was also the first time (1962) I wrote an article in regard to suppressors. My friends there said, “Gee, that’s neat. We’d like to get some.” I said, “I don’t want to build them, I don’t have time to do it,” but I sat down and wrote an article with some relatively crude mechanical drawings as to how to build one, and it was the glass pack muffler design, and actually gave a description of how it worked, and how the old Maxim worked, and why I thought the glass pack design was probably better than the baffled maxim. I got the idea for the glass pack from mufflers.

SAR: From car mufflers? I don’t remember ever seeing a suppressor with a glass pack in it in that time period.

Dater: I don’t recall seeing any others either but it became common in the Seventies designs. I used to do an awful lot of work on my old ’55 Triumph TR2, and it had a straight-through muffler in it that was basically a glass pack.

SAR: So you took automotive muffler technology and applied it to your sound suppressor to get rid of the streetlight that was keeping you from studying or sleeping at night, during medical school.

Dater: That’s correct. [laughter] The streetlamp itself was a big glass globe with a bulb inside. I don’t know what kind of glass it was, it was probably pretty good, but it made a little hole going in, and a fairly large hole going out, and the bulb itself was in the path of the bullet. I shot it out and the next day, I went downstairs, outside, to go to my car, and I looked at that and sort of laughed. Then I visually lined up the two holes from the globe, and there’s only one window that it could’ve possibly come from, and that was my window. They did replace the bulb, and I took that out a couple days later, but I used a water gun the next time. It’s amazing what a little bit of water on a hot light bulb will do: they shatter.

SAR: What about military service?

Dater: I went into the Air Force in September of ’65 as a general medical officer. I was in the Air Force for two years and spent the entire two years stationed in Roswell, New Mexico, at Walker Air Force Base, part of the 812th medical group. The commanding officer said, “We need a pediatrician. How would you like to do that?” And I replied, “That’s actually what I’d like to go into,” so I became a pediatrician at that point, and I had a board-certified pediatrician who was my supervisor. I had a wonderful two years there defending our country against the communist menace there in Roswell to the best of my ability. I don’t think there were any communists in Roswell; it was a very Republican county in New Mexico. I took care of the children of many of the military personnel who were serving in South East Asia.

SAR: Roswell is the place that they purportedly had the alien bodies. You were in the medical groups there at Roswell. Any comment on that?

Dater: No. We don’t talk about that.

SAR: (Uncomfortable silence) Uh, OK…. After your service, you were in the medical field, and you stayed in New Mexico?

Dater: I stayed in New Mexico. I started a residency in pediatrics at the University of New Mexico, which at that time, the hospital itself was Bernalillo County Indian Hospital. It subsequently became the University of New Mexico Hospital. I completed one year of pediatric residency, and then switched to radiology. My radiology residency was done in a private institution, Lovelace Bataan Medical Center.

SAR: Going back to the firearms and suppressors, in 1976 you were still in New Mexico, and you met with Sid McQueen.

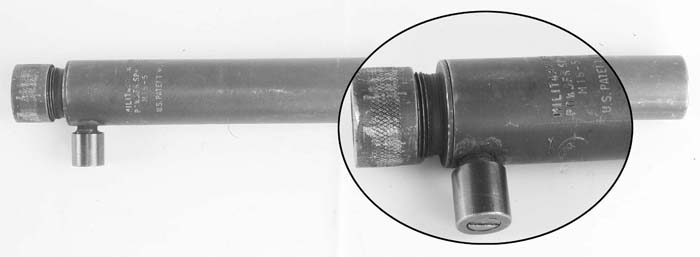

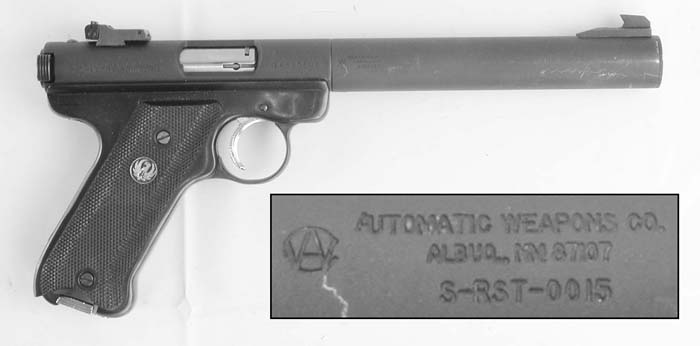

Dater: Yes, and I ended up buying two other silencers from him. One was an integrally silenced Ruger MKI pistol by Military Armament Corporation. I forget the model number on it, but I remember the silencer tube was approximately six inches long; it was a relatively compact unit. The other was an MA-1 for the M16 rifle. It had the teakettle whistle type thing on the side for pressure relief. Interestingly, Military Armament Corporation had forgotten to put the muzzle threads in this and some others of this model suppressor. This suppressor comes back over the barrel, and was supposed to screw into the barrel threads in the center support, and then there was a split collet at the back that tightened to the barrel and kept it from unscrewing. The people at S&S Arms thought that you just put the suppressor on the barrel and pulled it as far forward as you could against that internal support, and then tighten it down with a pair of vice grips. Amazingly, we didn’t have too many baffle strikes doing that. I figured out what was supposed to happen, how it was supposed to mount, thanks to J. David Truby’s Silencers, Snipers and Assassins and the diagrams in it.

SAR: You and David Truby have been friends for many years.

Dater: That correspondence started a couple years later. Sid McQueen is the guy who invented the Sidewinder submachine gun. Sid’s store was robbed once and he shot both armed robbers, killing one and permanently disabling the other. He used a registered M2 Carbine, firing 15 rounds and he said the reason he only fired 15 was the gun jammed. His family lived in the back and there was no way he was letting them be threatened.

SAR: What was your first suppressor design in that period?

Dater: I had that MAC made Ruger and after about 500 rounds, it started to get awfully loud. I called Military Armament Corporation, and asked, “How can I rejuvenate this?” The gentleman I talked to there said, “Well, there’s not much that can be done. The weapon was designed for a lifespan of 150, maybe 200 rounds. 40 or 50 rounds for qualification, then it would be taken out on a mission and deep six’d at the end.” It was not designed to come apart; it was not designed to be rejuvenated. The basic design on it was a barrel that was Swiss cheesed with holes, surrounded by stacked screen discs, sort of like the High Standard, HD Military. Then it had a wipe in the front, because MAC liked wipes. I asked if I could send it back, they said, “No, there’s no way to do that, because there’d be a tax coming back, and a tax going back to you.” They were absolutely wrong on that, but nobody knew the difference at that time. So I thought, well, they put it together, it has to be able to come apart, and that turned out to be a very difficult process. But I did disassemble it, and I found a way to repack it. The repacking was done using a copper mesh material, the Chore Boy, (at that time it was Chore Girl), pure copper scouring pads, and I figured how to modify those to have approximately the same density as the original screen washers that were in the unit. I repacked that a couple of times; it brought the unit back to normal performance. I decided I could improve the design, so, I called Sid McQueen and asked if I could build under his Class 2 license; I only had a Class 3 dealer’s SOT with a friend. I built my first prototype in a machine shop in the basement of the x-ray department of Lovelace Clinic. They had a full machine shop down there that wasn’t being used for anything else. I figured I might as well build instruments of death and destruction in the hospital. This prototype became, eventually, the model RST suppressor that I marketed under the name of Automatic Weapons Company, and the MKII Ruger that was later built under the name of AWC Systems Technology. This design used the 4-3/4 inch barreled Ruger. Basically, the back part of the barrel was Swiss cheesed, and had the Chore Boy copper scouring pads packed in there. Then there was a little separator, and then there was just a tube with a bunch of perforated holes in it, and a little bit of fiberglass wrapped around it. It was very quiet. The disadvantage was every 4-500 rounds, you had to disassemble it and repack it, but the instructions told exactly how to do it, how to prepare the material for packing. To see if the instructions could be followed by almost anyone, I handed a dirty gun to my sister with a set of instructions, said, “Here, repack this.” She found a few places where we had to modify the instructions a little bit for clarity, but she was able to do it. I figured if she could do it, anyone could.

SAR: You started Automatic Weapons Company in 1976?

Dater: Yes, but it wasn’t my Class 3 dealer’s license. Initially, it was a Type 6 Manufacturer of Ammunition. I got a little Star reloader, and I was going out machine-gunning with some of my friends on Sunday mornings, a group in Albuquerque led by a psychiatrist who billed himself as New Mexico’s oldest and largest machine gun dealer. He was older than the rest of us and he was more corpulent as well. And, he was a lot of fun. I started loading ammunition for other people there and figured I needed a license to do it. In ’78, my partner in our Class III dealership, which was called Historical Armaments, ended up in some legal difficulties, and ATF “suggested” that I divorce myself from him. At that point, I changed the Automatic Weapons Company license to an 07 manufacturer, and paid the Class 2 SOT. I also was making integrally suppressed Ruger 10/22 rifles. That was also around when you and I started talking about suppressors.

SAR: There was one major suppressor manufacturer at that time that had a production quality line and my company was a distributor for him. Other than Military Armament Corporation, there was Jonathan Arthur Ciener.

Dater: That’s absolutely correct. Jonathan, as I recall, actually started around 1975, somewhere in that area. In my opinion he is, more than anyone else, responsible for the civilian interest in ownership of firearm silencers. He advertised everywhere. I know I saw his ads in American Rifleman. They were in a lot of the gun magazines. I think they were even in Popular Mechanics or Popular Science. Little, one-inch ads about silencers, and his products were cutting edge technology for the era. Many of his designs were using baffles, not packing material. Some of them were a little larger than what I was doing, but they worked extremely well. If it hadn’t been for Jonathan, I don’t think that the civilian suppressor market would be where it is today. He was a pioneer. Jonathan was “it” on the civilian market, the leader. For the military, Reed Knight and Mickey Finn were both early on, Don Walsh also. I didn’t meet Reed until the early ’80s, and I know he had been in the business for quite a while prior to that.

SAR: One of your most popular designs was the SG-9.

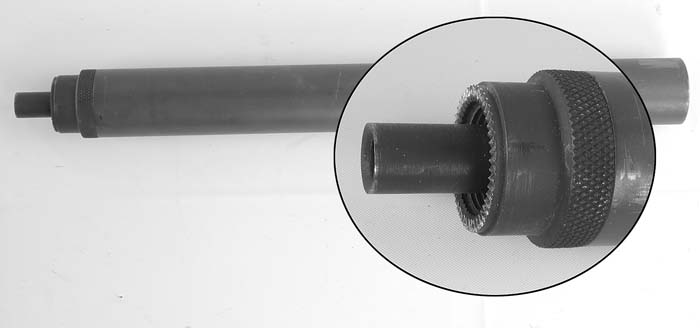

Dater: The SG-9 design itself came in, I believe it was ’78, possibly as late as ’79, and it was actually originally called the M-76, because it was for the Smith & Wesson 76. That was the first one. And the second one was called I guess SM2 for the Sten, and then subsequently it became the SG-9. The SG-9, which is made today the same way it was made in the late ’70s, used stamped baffles. The difference between the Sten version and the Smith version was the barrel and barrel mounting nut that was interchangeable in there. The interchangeability carried on to a little bit later in the early ’80s, either late ’83 or early ’84, when I designed what became the Mark 9 suppressor, that not only did I build under my Automatic Weapons Company license, but AWC Systems Technology ended up building also. That was a coaxial design, and the basic baffle stack, the basic configuration was my design on it. I had different barrel and mounts available for the Smith 76 and for the Mark II. Tim Bixler was working as the machinist for AWC Systems Technology. He took the design and made it into a very universal suppressor where all you changed was one little aluminum part at the back of the suppressor, and you could mount it on almost anything imaginable, including the HK weapons, the MP-5, which was coming up at that point in time, mount it on the Ingrams. The MK9 became a true workhorse. People still refer to it sort of as the standard of comparison for performance on 9mm sub-gun suppressors. Yes, it’s a little large. The original one was two inches in diameter and 12 inches long. About ’91, I redesigned it a little bit, came up with the MK 9K, which is still classed as a workhorse, and it too is pretty much a standard of comparison. We shortened the “K” up to where the overall length of the suppressor was seven and a half inches instead of 12, with more efficient diversion of the gases into the coaxial entrance chamber. The actual entrance chamber was surrounding the baffle stack.

SAR: The Bixler mount system, AWC Systems Technology had many different mounts for the MK9 series, for Beretta 12, MACs, I think there were about nine different mounts that you could get for it.

Dater: Well, it wasn’t an issue until ’86 that the ATF started having questions about suppressor parts, and the MK9 started late ’83, early ’84. Bixler, a very innovative machinist, came up with the interchangeable mounting system. It was a slight redesign in the entrance chamber, and also came up with the first practical 3-lug coupler and patented it successfully. It did not use any springs. In fact, he sold the patent to what has now become STW, and they’re producing that mount themselves. At Gemtech we’ve gone with Greg Latka’s mount, which is a push and twist and lock system.

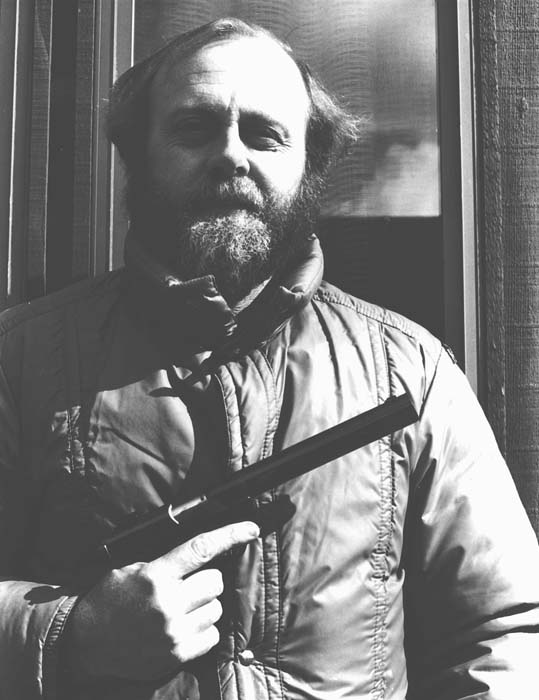

For most of these early designs, I was living in Albuquerque, New Mexico, working out of my garage, had a lathe, had a drill press, no milling machine. What little welding I did was done with oxyacetylene, and it tended to be more silver soldering. My products were basically hand-built, one at a time. There were limits as to what I could do but it was a great stay-at-home hobby for a doctor. When you’re on call, you stay at home and build silencers. [laughs] Sometimes, when I’d be on call at the hospital and had to stay there, I’d just go down to the basement and I’d work in their machine shop, which I had a key to. Automatic Weapons Company went fairly slowly for a number of years. Around ’79 or so, Chuck Taylor wrote a little short piece on my work. The first major piece that was written on my suppressors was done by Peter Kokalis. He came out and wrote it in August of ’81. Peter at the time was a freelance writer, had a few items published in Soldier of Fortune, and he’d asked Bob Brown for an assignment to write about. “Oh, there’s a suppressor manufacturer in New Mexico, why don’t you call him?” Peter came out and spent a couple days with me, stayed at my house. We went through a lot of the designs. Bob Brown came down for the photo shoot and the product demonstration. Peter wrote a fabulous article on my products. It was not really what you’d call a puff piece, because he was very honest in his evaluations. One of the things I did respect very much about Peter was that he did not try to take any product, which of course worked very well for me, because, being as small as I was, I couldn’t afford to give away much. He did buy some products, but he paid full dealer price for it.

SAR: That’s entirely appropriate, respectable, and it has been my policy all along as a writer, and it is SAR’s policy. Robert K. Brown is an operator with real world suppressor experience going back to the Sixties. What was Bob’s reaction to your suppressors?

Dater: My recollection is that he was very pleased with what he saw, but it was Peter’s article so he just enjoyed shooting. We had the silenced Ruger pistol; we had a Ruger 10/22 rifle. We had a couple for the M16 and one for the Sten and the Smith 76. There were several for center fire pistols. Bob certainly enjoyed going out on the mesa and shooting. In Albuquerque, we used to be able to just go out on the edge of town and shoot all kinds of stuff. It was not nearly as developed as it is now. I did go to a civilian gathering; Peter Kokalis invited me to come to one of Dillon’s earlier shoots at S-P (ShitPot) Crater in ’81. That was the first time I actually met Mike Dillon. I met a number of the people in the Class 3 community. We camped out there at the crater and did the night shoot, and just had a lot of fun.

SAR: What was the end result of the Soldier of Fortune article?

Dater: I got real busy. [laughs] Soldier of Fortune magazine was really on the way up. It was a relatively new magazine at that point. It started in ’75 as a quarterly and it had just gone monthly. It’s called “Doc Dater’s Deadly Devices.” It was in November of ’81. Somewhere along in that period, I wrote an article on suppressor design for SWAT Magazine, and it was in the Volume One, Number Two issue, Chuck Taylor had asked me to write it. It was a 5,000-word article, and what I didn’t realize, of course, was they only paid for about the first 3,000 words, and the rest of it was just sort of freebies.

SAR: Writing has never paid that well. Your suppressor line in 1981 was fully developed, for Automatic Weapons Company. I had a number of pieces from AWC, and I’ll be honest, Jonathan Ciener was where I was buying most of mine. Your product was also highly respected by people. At that time, in the civilian market, there was the new SWD product line, the old MAC stuff, the old RPB items, but they pretty much stayed to the MAC suppressors, some .22 cans, and M16 cans. There were a number of shops in the early Eighties that turned out clone cans of the MAC styles.

Dater: That is about right; there wasn’t a lot of production work in this business. I stayed by myself until probably about ’83. At that point, one of my customers in Friendswood, Texas, was Lynn McWilliams. He had bought a number of items, and he wanted to buy more than I could produce. Lynn said, “Why don’t you let me take over the actual production and manufacturing? You just do design work and I’ll pay you a royalty on the products that you design, that I build.” That sounded like a pretty good idea. I think my sales, before I joined up with Lynn, had been right around $25,000 a year. Of course, those are in 1981 or ’82 dollars which is about $250,000 a year today. [laughter] He started doing the production, and Tim Bixler was his machinist. Tim worked out of his garage, but he was an outstanding machinist, and he was more oriented towards production. I still manufactured some of the parts, and I had the engraving equipment, so I did all the marking on the suppressors. They came out for a couple years under the name of Automatic Weapons Company in Houston, Texas. In about ’85 or ’86, Lynn changed the name of his company to AWC Systems Technology. We continued to work together, until probably about ’89, when he hired Doug Olson who had been with Mickey Finn’s organization, Qual-A-Tec, and started to produce some of Doug’s newer designs. We sort of went our separate ways around then. It was very amicable. I still think very highly of Lynn McWilliams, and I consider him a friend.

SAR: Up until the late 1980s, where you had split off from AWC Systems Technology, what were the development levels of your sound suppressors?

Dater: We still were producing the integral Ruger pistols and rifles using some of the late ’70s technology, which was the shredded copper packing material, and the fiberglass. These were systems that worked; all of the projectiles were kept sub-sonic. Because of porting, the weapons cycled well: the accuracy was phenomenal on some of those weapons. It had to do with velocity control and making the bullet run at a speed where it gave its greatest accuracy for the twist rate of the barrels. On the center fire suppressors, of course, this sort of technology didn’t work. Others were machined baffles, usually out of aluminum. Fairly shallow M-shaped baffles, and one of the first M-baffles or K-baffles. This letter description is the letter that the baffle most closely resembles when it’s cut cross-sectionally. An M-baffle is basically a cone with a spacer that is built integral to it. It’s a conical baffle and spacer that’s been integrated. That was difficult for me to machine with the equipment I had, there was no automation. What I had were strictly manual lathes. What was easiest for me was to just make spacers out of tubing, and then stamping the baffles. Originally I ended up getting fender washers bought at the hardware store, and then I bought a hydraulic press and I made some dies and formed the baffles into shallow cones. Then I only had to trim the baffles, because they wouldn’t necessarily fit in the tube correctly. Eventually, I started having the washer blanks custom punched with a specific inside diameter hole, and a specific outside diameter, so that when they were formed, the hole on the inside would expand out to the size that I wanted, and the outside would constrict in, just enough to where it would fit inside the tube, and I could maintain good alignment throughout the entire suppressor. One of the things we found at that point was that the sound levels varied with the diameter of the hole in the baffle or the aperture. The tighter the aperture, the more gas was trapped in the baffle itself, and the exit of the gas was delayed more. The problem is that there’s always a little bullet instability. When the bullet leaves the rifling, it starts to spin in free air, which in this case is inside the suppressor. If you have the aperture too tight, which some people do even today, then you’re more apt to clip baffles. There’s a definite compromise in there. We did some experiments at AWC Systems Technology on a .223 thread-on suppressor where we tried various apertures. We started with a quarter-inch, .250 aperture throughout the suppressor, did sound measurements, then increased it 15 thousandths, did some more measurements, increased it again 15 thousandths, did some more. We found there’s probably about a three-decibel loss in performance with each increasing of the bore aperture.

Throughout the ’70s and most of the ’80s, we all used relatively simplistic baffle designs, that tended to have a lot of symmetry. This helped with the accuracy of the system. Around 1980 I started thinking, “I need to know exactly what we are doing. I need to get some reliable method of trying to do sound measurements.” I’d read the Frankfurt Arsenal Report, the World War Two study, where they had done sound measurements out on the field with a big microphone. The tests I remember were on the Sten, with and without the Mark Two suppressor. Non-suppressed, they were measuring 124 decibels or something like that. On the suppressed, it was down in the 90-decibel range, give or take a moderate amount. They were using a microphone that was fairly large. They were recording it on high-quality recorders, then taking it back into the lab, and playing the recorders into oscilloscopes to try and get the actual sound pressure levels. They were setting the microphone; I believe it was something like five meters from the muzzle. Well, I knew that the sound measurements they were doing did not ring true. I knew that the sound levels were higher than that. My first attempt at doing sound measurements was like many people at that time, with a little Radio Shack $39 meter. It gave wonderful results. I mean, non-suppressed .22s were in the 120-decibel range, if you could estimate how high the needle was kicking, because it didn’t have a peak hold or anything like that. I realized that didn’t work very well. I was talking with Don Walsh or Reed Knight, I forget which one it was, and they said they were using the B&K 2209 with the 4136 microphone. The non-suppressed and the suppressed results I was getting were nowhere near believable. I couldn’t afford the B&K meter at that time. I was doing acceptably well practicing medicine, but there’s only so much of that revenue that one can divert into the hobby, and my feeling has always been that any hobby that’s being run as a business has to be self-supporting, and not depend on capital infusions from elsewhere. The next sound meter I got was a Heathkit. This was their new digital spectrum analyzer. It was an interesting device. I think it actually went up to something like a maximum input of 130 decibels, somewhere along in there. I figured I’d just space the microphone out. I would get the energy level at each half-octave. But I didn’t really understand the concept of rise time at that point. The rise time on that meter was not very good. So the results were not totally believable there either. If I integrated all of the spectrum, I could come up with an [absolute] sound pressure level, which I didn’t quite believe. It was still measuring too low. If I took just one specific frequency, it was 4,000 hertz, it was closer to what I would’ve anticipated. On some of my early measurements, I looked at that one frequency as being what the actual sound level was. I was talking with Reed Knight sometime in the late ’80s, maybe it was ’87 or ’88, and he said, “You know, this company, Larson-Davis, has a meter that may do the job,” it was the model 700. So I called Larson-Davis, and I bought one of the meters.

SAR: Model 700?

Dater: Yes, Model 700. It had some problems. It had kind of a slow rise time, maximum input was 140 dB. After playing with that for a couple months, I realized it wasn’t going to do the job. So I called Larson-Davis and said, “Here’s what I need,” and I went through the specs that I needed, which included the 20-microsecond or better rise time, that was in the military standard. They said, “What you need is our 800B, and you need this microphone.” Then they made a wonderful offer. They said, “Since you bought the original model 700 for this one purpose, and it’s not suitable, we’ll allow you, as a trade-in, what you paid for the model 700,” and that was really a dealmaker. I got the 800B. Of course, from that point, all of the readings were completely believable and completely consistent with what the B&K did. I really credit Reed an awful lot with guiding me on doing sound measurements. It was the late ’80s when I got the Larson-Davis. Some of the catalogs that Lynn McWilliams and I did as AWC Systems Technology, we put in sound measurements that we got with some of the earlier equipment that really wasn’t doing the job quite right. But we were proud of the sound measurements we were getting. We should’ve been proud of them. The numbers were pretty good. Reed called at one point and said, “Phil, I don’t believe you’re getting the results you think you are.” He was absolutely right.

SAR: In the early ’80s, you started having concern about scientific testing of sound. As a physician, at what point did you begin to get concerned about hearing loss and hearing damage from firing weapons?

Dater: It was around the same time. I hadn’t really gotten into knowing what was safe and what wasn’t safe. I hadn’t really studied that very much. But it was around that time that I began to realize that I was having hearing problems. I shot many tens of thousands of rounds through machine guns, through sub-guns, hunting turtles with the sheriff of Allen Parish, Louisiana, and with some of my friends, this sort of thing. “Real men don’t wear hearing protection” was what we thought. While getting ready for quail season or pheasant season, we’d go skeet shooting with my stepfather. You’re on a 12-gauge for 25 shots per round and usually run about four rounds. What was even more irritating was the ringing in my ears continuously, which has not gotten better, but fortunately hasn’t gotten a whole lot worse since I started using sound suppressors. Then I read that the VA spends on average approximately $4,000 per year per veteran in hearing damage claims. I know the kind of sound levels that some of those troops have been subjected to. It became a real issue and sound suppressors on firearms can definitely help.

SAR: You’ve written about sound testing, due to your concern about the misinformation that the whole industry had about sound suppressors.

Dater: I currently still publish a pamphlet on this. I wrote an article for Small Arms Review on Firearm Sound Testing (August, 2000). I had read the Mil Standard – 1474c – what it was saying about the equipment requirements. I also knew what levels were believable and what weren’t, and I would hear people say, “We did measurements and we’re getting 48 decibels reduction,” or some bizarre number, and I’d ask what the suppressed and non-suppressed was, and the suppressed levels were running a way lower than they should, or the non-suppressed were running a little lower than they should have. I could look at that data and explain, “Your microphone or your system does not have the rise time to actually catch the peaks.” In the mid ’80s, a friend of mine who worked at Sandia Labs said that even in 20 microseconds, you’re probably missing a good deal of the sound level peaks, because they’re of shorter duration than that. “We know, we blow up things, and we measure sound pressure levels. We have transducers that pick up sound impulses that have rise times of less than 20 or 30 nanoseconds, much less microseconds.” I said, “Gee, what do those transducers cost?” He said, “Well, they run about $1,000 each.” I said, “That sounds great.” He says, “Yeah, but they’re only good for one shot, and then they’re toast.” That, of course, was not practical.

There were, and are, a lot of people who try to promote their product, testing with equipment that just flat out wouldn’t do the job. The famed Radio Shack meter, or the meter by Quest that had, I think a 100-microsecond rise time, missed most of the suppressed pulse. During that period, Al Paulson was starting to do silencer reviews. Al and I talked a lot. Some of his very early reviews of some of our product actually used some of the data from my spectrum analyzer. Then he decided that, and rightly so, that he needed to get his own meter, and he got a B&K 2209. We worked together, comparing a lot of the test results that we got. Al got very good results. His results were believable and accurate, and Al’s a true scientist. I’d written something previously that Al ended up quoting in his book, Silencer History and Performance: Volume One.

SAR: A number of other people who were in the industry shared information.

Dater: In those days, you would be hard pressed to think of a suppressor designer who wasn’t willing to share non-proprietary information, to discuss the science with others. There really was a Renaissance of suppressor design from the 1980s-90s. It was an exciting time in this business. That was around the time I was getting ready to leave New Mexico. I still built a few things under the old Automatic Weapons Company name, which is a name I still maintain. I had incorporated in the meantime. The corporate name is Antares Technologies Incorporated, doing business as the Automatic Weapons Company. Originally, it was to be just the corporate structure for the building of suppressors, but it ended up becoming more of a consulting firm to the small arms community.

SAR: You’ve worked with a number of clients over the last 20-odd years, on firearm and suppressor design.

Dater: True, but my prime focus as a business is my partnership in Gemini Technologies; Gemtech. After I moved to Boise, Idaho, in ’91, I started to build again under the Automatic Weapons Company name, and sold a few items. I actually even ran a small ad in the old Machine Gun News, including an ad to do sound measurements for other manufacturers, because I knew that I was doing them correctly and could be of service. That’s why I was happy to get involved with the Suppressor Trials you ran for Machine Gun News in 1997, as well as the 1999 Suppressor Trials for Small Arms Review.

SAR: You were one of the volunteer testers – brought your own meter. Al Paulson did, Dr. Chris Luchini and Dr. Reagan Cole from the University of Arkansas were there as well, all running parallel meters during the 1999 trials. It really was like a Renaissance, with all the great information being shared.

Dater: The first one at Knob Creek in 1997 was right before Machine Gun News went under. Al Paulson and I were there, and we both ran our meters. Mine ran a little easier, because the Larson-Davis has the real beauty of being able to be driven and read by a laptop computer. I could assimilate and do the analysis on the data faster than Al could on his B&K, where he had to handwrite everything down and then do all the math. The results that we got were, between the two meters, basically identical, maybe a half-dB difference on the averages. We learned an awful lot in that trial. One of the things that we were doing was, and you were there, Dan, we had the ammunition out in the sun, and we started off early in the morning, running all of one manufacturer’s suppressors. It was about 50 degrees out and it was just miserably cold. By mid-afternoon, when it was up well into the 90 degrees, we were getting into some of the other manufacturers, which included some of our product, and the ammunition had been sitting out in the sun all day, the ammunition was physically hot, and the pressures were a little high, and the sound levels were certainly off on all of it. We learned that you don’t do testing of a given manufacturer, and complete all of his stuff, but as we did two years later at the 1999 SAR Suppressor Trials, you do categories of suppressors together. That way, you have less variation from the climatic changes that occur during the day, and of course all tests include the environmental data. One of the things I’ve learned over the years is that measurements made on a cold day are not necessarily going to be the same as those on a very hot day. There’s an awful lot of variation in actual sound measurements. When we did the test under the auspices of SAR in ’99, we were, I believe, a lot more accurate in that we were doing. With Drs. Luchini and Cole there doing spectrum analysis parallel to the B&K and Larson Davis meters we were seeing the time curves and spectrum curves. Unfortunately, Al had a bad microphone element. Regardless, because I was involved in the testing, allegations were made by a number of people that I cooked the results. John Tibbetts was standing there, looking over my shoulder at every single shot that was fired, no matter whose it was. John said, “There’s no way you could’ve cooked the results, I was watching your results too.” And a few of our things didn’t perform as well as we thought they would.

SAR: I’ve got to take some heat on this, because we never published the full set of results on the 1999 suppressor trials, and there were allegations that that was done to protect some manufacturers. Total baloney, it was my call. The fact is that the guys who were supposed to write this into a book didn’t turn in the coordinated end results for over a year. It was incomplete and had formula that didn’t work, and there was no way we could do anything with the information we had because it was incomplete and too easy for people to misread or misquote. Rather than take all those results and put them out as a skewed group with everybody picking at it, I chose not to publish it. The information was given to every manufacturer tested. They all had their own information, but we never published the entire thing, because of the timeliness of it. It was bordering on irrelevant as a body of work.

Dater: By the time all the data was available; a lot of people had progressed on to different designs in their production models. What was great about those two suppressor trials, the first one in particular, was almost everybody in the industry was there, with maybe one exception. Everybody who was making suppressors was there, and had their stuff out. Tim LaFrance was talking about all his experiences with people, and the newer suppressor manufacturers were getting hints from the older guys, and there was a real sharing of scientific information at that first one. The second one, there was a little bit more involvement, but there were some people coming in and trying to “trick” the tests, taking what was supposed to be a dry can and putting a little bit of oil in it, and you could see smoke coming out of their cans. There were people trying to skew the tests. That defeated the purpose of the whole event. There are a number of issues with some of the published testing results. We at Gemtech, and Lynn McWilliams at AWC have always been very honest in our test results even as we refined our testing methodology. There was a time, certainly in the ’80s, and maybe into the early ’90s, when we all published the dB ratings, but we stopped doing it for a number of reasons. One of them was that as we got more experience, we found there was a lot of individual day-to-day variation that went on; there was variation with the ammunition used, with the temperature of the suppressor and the weapon. We found that on an extremely hot day, like a nice summer day with ambient temperature of 110 degrees in the bright sun, nobody’s suppressor measures extremely well. Humidity makes a difference as does barometric pressure and altitude. There are just too many variables. The other thing is that when we would measure things, we would do a string of ten rounds, and we would take an average of the ten, we didn’t just pick one or two rounds, we didn’t throw out one or two, we averaged all ten. The results we would get today would vary one or two dB from what we get tomorrow, or what we got the day before. So, on a given day, at a given time, under given circumstances, the sound results are absolutely correct. The problem is that not everyone measures the same way we do. I’ve heard manufacturers say, “My suppressor is doing 38 decibels,” and I would say, “Did you actually measure it?” “Well, no, but I compared it to one that I measured previously, that I measured at 34 decibels, and it sounded like it was at least four decibels quieter, so this one is doing 38.” I don’t think anyone’s ear is that good – especially a shooter who has hearing loss like most of us do. The other thing is we had heard that there were groups or manufacturers who would run a string of 20 shots, and pick the one best shot, and say, “My suppressor does X dB reduction.” Al Paulson has always measured the string of ten rounds, and has published the average. Usually, he also has the extreme spread in there, and he does a good job. When you’re going to measure a suppressor, you really need to buy one off the shelf from an independent dealer. If you want a brand X suppressor, go to a dealer and buy the brand X from him. Don’t order it directly from the company, or don’t accept it directly from the company, because you don’t know that you’re getting a production item. You may be getting a tricked item. We have measured suppressors that have had some fairly wild claims as to performance, and we’ve never been able to reproduce those results. Other people that we know who know how to measure firearm sound have measured the same suppressor and not been able to reproduce the claimed results. So, the question always comes up: Was the unit that was set up “tricked?” Did it have an extremely tight aperture for some reason?

SAR: In the real end user world, that wouldn’t function properly.

Dater: No, or wouldn’t function with a moderate amount of full auto fire. At the ’99 trials, there were one or two manufacturers who claimed they were doing dry pistol suppressors, and you could see a stream of steam come out, and we actually started shooting the first shot through a piece of white typing paper to catch water or grease or whatever, to determine if the unit was “wet.” Almost any pistol suppressor is going to be 10 decibels quieter if it’s wet. It was depressing to me to realize that, from that first time that we tried it, where there really was this incredible exchange of scientific knowledge and mentoring, and just a great experience, by the second trials, there were people who were coming in, trying to trick the testers, trying to get better numbers instead of trying to find out what they were really doing with their suppressors.

SAR: That’s the reason I haven’t done another trials. I’ve been a bit frustrated because there are things that I call fan sites that are put up on the Internet, and they pretend to be objective, and they use bad science and they use inaccurate but flattering testing. We won’t give any validity in Small Arms Review to the sites that are shills for manufacturers. That’s just something that our readers and especially our government readers need to be acutely aware of, is that just because it’s on the Internet does not mean it’s true, and that there are some people who are skewing numbers, and putting up unscientific data, and pretending to be objective, and they’re not. We’ll have nothing to do with that, because procurement people and general customers are making decisions based on what amounts to baloney. Who suffers in the end is the guy on the ground with the gun. That’s unacceptable.

Dater: That’s correct. It was exhilarating to be part of those two Suppressor Trials, and I wish you could get a government or academic group to sponsor and provide oversight for another Trials, to take the baloney out of it. One later outcropping of the open testing environment we were having was that in late ’92 or early ’93, Jim Ryan of JR Customs responded to my ad in Machine Gun News about doing some testing. He and his partner, Mark Weiss, came over to Boise, and we did some sound measurement testing. He said, “What can we do to improve the product a little bit?” I said, “You might try a little bit of this, little bit of that,” based on my experience and what I was doing to a certain extent at the time. As 1993 progressed, Jim made the suggestion, “Why don’t we just join forces and make a new company?” Out of that, Gemini Technologies Incorporated was born, and it uses the trade name Gemtech, which has become almost a household word in suppressors these days. For the first couple years, Jim worked in Washington and I worked in Boise. Then about ’96, he moved to Boise, and we started working together on a day-by-day basis. We started to produce more and more product. I think the first year we turned about $15,000 in sales in the new company. In early ’94, Greg Latka joined Gemtech, from his company, GSL Technology. He had been corresponding with Al Paulson. Al said, “You ought to talk to these people at Gemtech, they have some good ideas, and you have some good manufacturing capability, and that sounds like a good match.” It certainly was. Greg is still with the company. We’re both actually classed as consultants, but we’re heavily involved in the day-to-day operation of the company.

I think the 1990s were the Golden Age of suppressor design. Just look at the groups that were out there – Knight’s, AWC Systems Technology, OPS Inc, John’s Guns, I don’t want to leave anyone out but the list goes on and on, and if you compare the before and after out of that decade, it’s amazing. When Jim Ryan and I started, we were using ’80s technology, using some fairly simplistic machined baffles. Greg opened our eyes as to the capabilities of CNC Machinery. He is a very innovative machinist, and is also a very good designer. It’s hard for me to say exactly who was responsible for which innovation that we made. Certainly, as a company, we made a lot of innovation. The so-called K baffle is not a new concept. It dates back to a patent in the late ’20s or early ’30s, which never went anywhere. Then some fine tuning that Doug Olson did when he was working with Qual-A-Tech, where he was using flat baffles with some strange geometry in it, and conical spacers instead of straight spacers, which had been the prevailing wisdom. Those two together, if you made them as one piece, was sort of a K baffle. We started using the K baffle in production, and we were the first of the suppressor companies to use it actually as a production item. We made our changes to the way gases were diverted in both the Olson design and some of the earlier designs, in that we were using scoops instead of slanted sidewalls in the baffle, which was a more effective method of production. The K baffle, of course, was not a patentable item, at the time that we were making improvements in it, and it has been very widely copied, has become kind of the standard of the industry. It’s probably the most efficient baffle for its size. It is a little pressure-sensitive, and there are some pressures that it really doesn’t work very well with, including the .50 BMG caliber. We had an interesting experience with that. We made a .50 suppressor, and we fired the first shot on the Barrett rifle, pulling the string, and it worked real well. Jim Ryan fired the second shot, and he thought he broke his shoulder, because everything sort of came apart at that point, as the suppressor itself launched downrange. The K baffle has one disadvantage. It has a certain inherent weakness, due to the direction of vector forces in the structure. What had happened on the first shot was some of them had collapsed a little bit. And the leading, instead of being about .55 caliber hole throughout the lead, was about .70 caliber, but the exit port was about .40, and of course that’s just a little bit too tight for the .50 caliber bullet, and the unit went downrange. Newtonian physics being what it is, the recoil was fairly intense.

SAR: Three pounds going downrange, with an equal and opposite reaction onto Jim’s shoulder. [laughter] I remember that phone call from Jim.

Dater: We all laughed about it later, but there was an initial concern that he might’ve broken something. But that’s part of the R&D process. You learn things. Take Ops, Inc. – Phil Seeberger. He’s a fascinating character. He started in the mid-’80s, and he had some theories about a mechanical phase cancellation, which may or may not have worked the way he says. But he certainly built some product that worked quite well. It was fairly lightweight. But again, there was a lot of innovation, a lot of thought process that was going into it. Military Armament Corporation really popularized the “wipe,” a WWII concept seen in the Welrod and other suppressors of that era. The wipe is a piece of rubber or urethane or similar material, with a little hole in it that is seriously less than the diameter of the bullet. The whole idea is that as the bullet passes through the suppressor, it hits the wipe, it exits out, and then the wipe material snaps back and sort of locks the gas in the suppressor and lets it come out fairly slowly, cooling and interrupting the gas flow. The problem is that anything that touches the bullet in free flight once it has left the rifling, causes horrible accuracy problems. If you’re using a hollow point or a soft point, high velocity projectile, you’ll just have the projectile disintegrate right at that point. It will go ahead and expand. Wipes were seldom used in anything other than pistol calibers, the potential accuracy issues were terrible. The Knight’s Armament early pistol suppressors, the Hushpuppy, used a number of wipes in it, to give a very compact unit. Reed told me once, “It’s very quiet, but it’s not being shot at 50 yards, it’s being shot at one to two yards, and at that range, the accuracy is not an issue, it’s not going to be deflected that much.” There certainly were uses for the wipes. The problem, of course, was that they had to be replaced on a fairly frequent basis. Military Armament Corporation used them. We, at Gemtech, got away from wipes completely. As Automatic Weapons Company, I never used wipes.

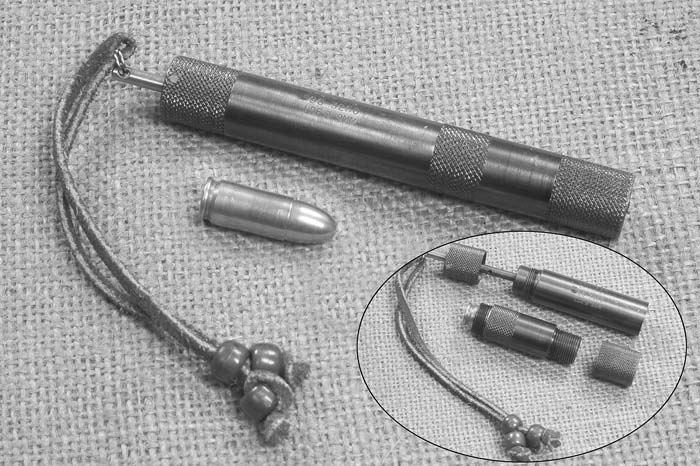

SAR: But at Gemtech, you did have one wiped can…

Dater: We had one wiped can, it was the Aurora, and it was a nine-millimeter pistol suppressor that was 3-1/4 inches long, and 1-1/8 inches in diameter, and it had wipes in it, and some grease for artificial environment technology. It did an honest 25 decibels reduction on the first shot, and deteriorated from there. It was designed, really, as a 10-to-12-shot suppressor. That’s strictly last ditch effort. It was designed to be in the pilot’s bailout bag on say, a Glock 26, which is a very compact 9mm pistol. The idea was a downed pilot, if he is discovered, can use it at basically a one-to-two-yard range, to take out a sentry, take out the person who has just discovered him, or to take out an enemy combatant, so he can steal his uniform, overcoat and his rifle. Strictly for evasion. It was not intended for backyard shooting or target shooting or anything like that. We also had a 9mm pen gun that looked like a mini-kubaton. It had no projections sticking out the side. It was four inches long, 9/16 inch in diameter, and the first run of 20 used 9x19mm. The subsequent ones use the .380 cartridge, which was probably a little better suited. It was kind of miserable to shoot. You could put it on a keychain, nobody ever spotted what it was. In fact, one of our customers, before 9/11, was going through airport security, and he threw his keys in the tray, and when he threw the keys there, he spotted his LDE-9 pen gun on the key ring. He said he had a real adrenaline issue until he got through the other side, and they handed him the tray and said, “Here’s your pocket contents, sir.” [laughter] Not a product we offer anymore. We probably built about 30 or 40 of the .380s. Our core product has been silencers. That’s what we wanted to concentrate on. When you start producing firearms themselves, then you have the excise tax issues to deal with. The way we legally avoided the 11% excise tax on those pen guns was we just sold them all out on a Form 4 with the $5 transfer tax.

SAR: Under section 4181, that if the Form 4 transfer tax is paid on the first transfer out of a manufacturer or importer, there’s no Federal Excise Tax owed, because the transfer tax is an excise tax and the first payment counts.

Dater: That’s correct. As an “Any Other Weapon,” it qualified for the $5 transfer tax. Of course, we had dealers who were really unhappy about that, because even though they didn’t have to do the fingerprint or sheriff’s signature, they didn’t get transfer approval as quickly.

SAR: Using the Form 4 front only method of transfer directly from the manufacturer can certainly save some FET money. Phil, In today’s market, there are basically four companies that come to mind as working the major contracts, the military contracts. Knights Armament clearly is the leader in government contracts on suppressors. Gemtech is certainly in there, with Surefire, and Ops Inc. as well. These four suppressor brands are the ones mostly seen overseas in our military’s hands, although there are other shops selling to government agencies.

Dater: I think these are probably the major ones. Surefire’s a relative newcomer to the suppressor field, but they have phenomenal manufacturing and marketing capability and contacts, because of their flashlights. They have a decent product. Don’t forget, however, that there are other manufacturers who have made sales to the government. It’s extremely difficult to get to that Holy Grail of a real “contract.” The true government contract is frequently the death knell for a small company, because of the strings the government puts on everything, to make sure they’re getting their money’s worth. We get primarily large “sales orders” at Gemtech as opposed to “Contracts,” and that suits us just fine. There are contracts, and there are sales orders or purchase orders, and they’re different things, and there are a lot of small companies that have received a purchase order for a production run, a small run. But a genuine military contract, well, the companies that have actually achieved that, or can afford it and handle it when it happens are few and far between. The main one that comes to mind is Knight’s Armament. They’ve been having actual honest to goodness contracts for years. The truth is that if somebody really is working in that field, the government doesn’t really appreciate them talking about it.

SAR: That brings us around to advertising suppressors. The internet has given rise to a new level of suppressor advertising and claims being made, as well as guerilla marketing being done by companies. Are you seeing innovation from some of these companies?

Dater: Not many. Look, guerilla marketing is fine as far as that goes, people need to try to build business. However, the vast majority are basically taking a product that another company has developed, and has been marketing successfully, making a few extremely minor changes to it, perhaps changes in the method of assembly or actual manufacturing, without changing the product itself very much, and putting it out under their own label. I believe that certainly in the civilian marketplace, that the ’90s was where the majority of the innovation had occurred. Innovation in anything goes in jumps. There’ll be some innovation, and then there’s a plateau that goes for a number of years, and then all of a sudden there’s an increase in innovation, and then another plateau. Now, some companies will take the innovation that others have done, and just copy it absolutely identically. Some will find very minor changes, and some will use, actually, older concepts and older designs, and make some truly major changes to it. That ramps up the next slope of innovation. Unfortunately, there are a number of companies that don’t make true innovation. Changing a thread pitch is certainly not innovation. Rather, they just copy other’s products. They may change manufacturing technique. If you find a specific design that works, and that you like, that is machined parts, and you change it to casting, that is a manufacturing innovation, but it is not a technological innovation. The same thing with taking discrete parts and merging them into a module. That, again, is a manufacturing issue. It’s not technological innovation. At best it’s flattering to be mimicked, at worst, it’s frustrating to see the level of intellectual theft a few of the newer shops are stooping to.

SAR: Phil, you have had over 30 years of time that you’ve worked intensely on designing suppressors, and to stopping hearing loss, and have led the charge in Gemtech, one of the groups that’s been at the forefront of the suppressor industry for many, many years. I’d like to explore a little bit aside from that. I know with Antares Technology that you do suppressor seminars.

Dater: I do. As Antares Technology, I’ve traveled fairly extensively in Europe, and now in Asia, examining historical suppressors, suppressors manufactured by contemporaries abroad, and I’ve done sound measurements for a number of European manufacturers under contract. I do not divulge the results that I get. If they wish to divulge them, they’re certainly free to do whatever they wish. But I have studied a lot of the historical suppressors, things not common to the community, such as Welrods, DeLisles, Chinese Type 67s and the suppressed Makarovs. (Read Doc Dater’s take on historical suppressors in the next issue of SAR.) The training seminars I have done are in sound suppression issues and hearing damage issues. I just completed teaching a two-day course at LMO in Nevada on sound suppressor design, function, hearing loss, and sound measurements; mostly government clients. My prime interest has been in sound measurements and hearing damage, but it’s awfully hard to get up and talk without going into a lot of what makes the things work. They’re not just sound catchers you buy at the auto muffler supply store. There is some real science to suppressors. I’m interested in the designs, I’m interested in teaching. I’ve accumulated 30 solid years of knowledge in suppressor design, and I enjoy sharing it.

SAR: You’ve also worked on consulting projects with a number of companies in the small arms.

Dater: We really cannot discuss it, there are confidentiality issues. I am available for consultation on firearms design and sound suppression issues. Some of my European competitors have hired me to do sound measurements so that they have measurements utilizing the US system and the US technique, and what has become a very standard procedure, so that they can compare their product with products built in the States.

SAR: Jim Ryan left Gemtech in 1998, and Mark Weiss left at the same time.

Dater: Yes. Kel Whelan came into Gemtech, I believe it was March 2000. He came over from Weapon Safety, a retail store in Bellevue, Washington. He was in charge of their Title II sales department. He saw an opportunity with our small blue sky company, and he came in to be in charge of our sales and marketing, and has done an excellent job. He’s been a wonderful addition to the company.

SAR: The trend in suppressors through the ’90s was to try and make them smaller, quieter, narrower, trying to compress them down to a certain point, and there were some issues that came out of that.

Dater: There were definitely some issues. The first thing is, the suppressor marketing people analyze the market and say, “Well, here’s what the customer wants: a silencer that works just as well as it did in the Antonio Banderas movie, ‘Assassin,’ and it is one inch in diameter, three inches long, will work on anything from .22 long rifle up through .50 Browning, and does 40 decibels reduction. That’s what the customer wants.” The customer, unfortunately, does not understand the basic laws of physics. At the moment the bullet leaves the bore, you have a certain volume of gas at a certain pressure and temperature that you have to deal with, and you have to drop your pressure one way or another. When you start making things too small, you are not dropping your pressure enough, and one of the things that happens is that the pressure stays higher in the bore for a longer period of time and cycling becomes more violent. As the cycling becomes more violent, and the cyclic rate goes up because of the violent cycling, you start beating the crap out of your gun, and you shorten the life of the weapon. Yeah, it may be smaller and lighter weight, but the reliability of the entire system is diminished. People don’t realize that suppressed weapons are a system; they’re not just an accessory you hang on like a flashlight. The other thing is that you’ve got to have some volume in the entrance chamber. There are people who have made really short cans, and they’ve taken the blast baffle and just shoved it up almost right against the muzzle. And in .223, at least, and especially in the shorter barrels, you’ve got a lot of unburned powder particles that are coming out like a plasma jet of superheated sand. Not only does it seriously sandblast the blast baffle, but it also sandblasts the muzzle. There have been some designs, the Smidget was one, that Al Paulson said at about 75 rounds, absolutely ruined the accuracy of his rifle because it eroded the muzzle. These are concerns. When you’re dealing with the pressures that you’re dealing with, you have to put in a margin of safety for your wall thickness of your tubing, so that you don’t end up rupturing the side of the suppressor and blowing stuff out the side, or breaking welds, because the entrance chambers are not designed properly. There’s a lot more to designing a suppressor than letting a monkey stick washers in a piece of pipe.

SAR: With suppressors there’s always been kind of a “spy thing.” There’s a mystique to suppressors and using these items, and I think what you’re pointing out here is that beyond all of that, there has to be sound understanding of the laws of physics, the mechanical things that are involved, the construction of all of it, and how a heat engine actually works.

Dater: You’ve got to understand thermodynamics, you’ve got to understand strength of materials, you’ve got to understand flow dynamics; all these things enter in there. This gas is a fluid that is flowing, and you’re creating turbulence and you’re trapping it here and there, and it’s going to dump heat wherever it happens to be, because it is significantly hotter than the ambient temperature of the suppressor. A lot of folks just do not understand that.

SAR: To be simplistic, exactly what does a suppressor do?

Dater: A suppressor reduces the sound of the muzzle blast, and that’s all it does. It does not eliminate the sound, but it reduces it down to where it is not perceivable from as great a distance and it helps confuse the target because the target does not hear the muzzle blast and can’t localize where it came from. Basically, the suppressor is taking the high energy that is being suddenly released at the moment the bullet uncorks from the end of the barrel, and it is releasing that slowly into the atmosphere and cooling it. The best example is one I use in my classes: You take two party balloons and blow them up. One of them you put a pin into and you let the pressure out almost instantaneously, and it makes a big pop. The other one, you undo the valve on, let the pressure out over about a two-second period, and there’s very little noise associated with it. You still dealt with the same amount of energy. It’s just you’ve done it over a different timeframe. Suppressors functionally work by reducing temperature through conduction, convection, radiation. That reduces pressure. Reduced pressure by increasing the volume, and then spread out the time curve, the time exit curve.

SAR: There’s a design goal to have a suppressor that can go in a belt-fed weapon and work for 1,000 rounds full auto, belt-fed through the gun.

Dater: The other issue you run into immediately is heat buildup. Most of the steels that are used in suppressors, whether it’s chrome-moly or whether it’s 300 series stainless, which everybody likes because it is more rust-resistant than chrome-moly, the core temperature of your suppressor goes up to about seven and a half degrees per round, up to around 1,000 degrees, and then rate of increase diminishes. But at 1,000 degrees, that steel has approximately 6% of the tensile strength that it had at room temperature. You’ve got to have a margin of safety in there when you start getting these things real hot. The other thing is on .223, and it does not happen on other calibers, but on .223, the projectile has a real large surface area and a real small mass of lead. The friction of shoving this projectile through a piece of pipe that is smaller in diameter will generate an awful lot of heat. The heating of the barrel is more from the friction than it is from the actual flame temperature. When the bore temperature gets up over about 650 or 700 degrees, and a suppressor will actually increase the rate at which the bore temperature goes up, then with the large surface area of a very highly heat-conducting metal, that is copper, and the small mass, that mass of lead in the center starts to melt, or certainly it starts to soften. Lead itself melts at around 650 degrees F depending on how it’s alloyed. When that happens, the bullet destabilizes. As soon as it leaves the muzzle, it starts to yaw more than normal. If you have a reasonable aperture through your suppressor, you’re going to start clipping baffles. Now, if you want to have a suppressor that’s going to do 500-round dumps on an M249, you’re going to need to open up the aperture throughout the entire suppressor to probably .38 caliber or better. Most people have taken it up to about three-eighths of an inch. Then it doesn’t matter if your bullet yaws pretty badly, because you still have plenty of clearance and you’re not going to clip baffles. Otherwise, I can just almost guarantee you’re going to clip the front end cap and clip some of the baffles, somewhere between 150 and 200 rounds.

SAR: Now we’re back to “You can’t repeal the laws of physics” that are involved in all of this design.

Dater: Precisely. Many of today’s designers, and that term I’m using awfully loosely, because I don’t think there are a lot of true designers out there, are just putting together things. They see a sketch from here, they see a photo from there, they say, “Any fool can do this,” and they build it. But most of them do not understand what’s going on in there. There are not a whole hell of a lot of mechanical engineers who are designing suppressors. Doug Olson is one, so is Joe Gaddini. I am being a bit severe here as there are certainly others who do understand the interior ballistics, and are in this industry.

SAR: The other guys look really cool in black ninja outfits with a suppressor when they put their pictures on YouTube.

Dater: [laughs] I won’t say anything there.

SAR: That’s OK, I will. YouTubing is hurting our war efforts and creating misconceptions on a massive level. I think the next big set of firearms restrictions is going to be blueprinted by the YouTube ninjas as the anti-firearms proponents gather intel on what is “scary” next. Phil, any message in particular you want to pass on to our readers?

Dater: Yes. Let me start by saying a little something about Sid McQueen, who was a truly innovative firearms designer. He was not exactly a suppressor designer. Most of the suppressors that he built, I designed, because I worked with him fairly closely on a number of issues. He designed the Sidewinder submachine gun, which was a truly unique weapon, and generated about a half dozen patents for him. He was always designing, always innovating. When the ’86 law passed, this was really a true disaster. Sid had a new assault rifle on the drawing board. The way Sid would design some of the stuff is he would make a drawing, then he’d cut out cardboard parts, and he’d stick pushpins in them, and see how various surfaces interacted. I’d never seen this done before. I suspect it’s probably not uncommon, but certainly that’s the way Sid did it. When the ’86 ban passed, he rolled up his designs, put them in a filing cabinet, and has not looked at them again to this day.