By Sam Pikula

Of all the countries in Europe, my favorite without hesitation has to be Switzerland. The scenery is breathtaking, the people are friendly, you can drink the tap water without worry, and the gun shops are great. You can walk into a Swiss gun shop and find all of the really neat guns which can’t be imported into the United States: Vektor L-4’s, MAS 5.56’s, AK-101’s, Saiga combat shotguns with folding stocks, etc. The Helvetian Confederation, more commonly known as Switzerland, has some very liberal gun laws (liberal in the classic sense of the word that is). As most people know Switzerland hasn’t been involved in a war for hundreds of years and follows strict neutrality. There are two notable reasons the Swiss have been able to maintain this neutrality: guns and geography.

Switzerland’s picturesque scenery is mostly due to the rugged beauty of the Swiss Alps. This imposing terrain when even minimally fortified presents a formidable obstacle to an invader. In fact the terrain is so rugged the Swiss Army is one of the few modern military organizations in the world that still uses horses and mules as nothing better has been found for mountain transport. The second reason the Swiss have been left alone by the great powers over the march of time is their well-armed citizenry.

For centuries every able bodied Swiss male had to undergo military training and was required to keep his weapon at home. For instance one of my Swiss friends has the 1911 Model Schmidt-Rubin rifle his grandfather was issued, the 1931 Model Schmidt-Rubin that his father was issued in 1940, and now has his issue full auto Sturmgewehr. When their military term of obligation has expired (30 years), Swiss citizens have the opportunity to buy their issue weapon for a nominal fee. It has been this way for generations. Unlike the rest of Europe, which had masses of downtrodden peasants and various levels of privileged nobility, Switzerland has always been composed of free citizens. Where most European countries distrusted and feared an armed populace, the Swiss embraced it. Switzerland has remained free because its citizens have been ready, willing, and able to use their personal weapons, be they crossbows, pikes, muskets, or rifles to defend their borders.

In order to arm their people the Swiss Confederation in its early history (the 1500’s) decided to maintain a series of arsenals across the country. Switzerland is composed of 23 Cantons. A Canton is roughly equal to one of our states however unlike our “federation” the Cantons are not as subordinate to the central government. The goal was that each Canton would have its own arsenal. This was done to varying degrees but over time the centers of Swiss arms production gravitated to three main arsenals found at Neuhausen (S.I.G.), Bern, and Solothurn. Several months ago a Swiss friend of mine offered to be my guide and show me the Arsenal Museum at Solothurn which I gladly accepted.

The city and Canton of Solothurn (pronounced “Soloturn”) is located in northwest Switzerland. In 1463 the arsenal was first mentioned in Swiss records as an “armour hut and spear house”. In the next century a gunsmith foundry and powder mill was added and the area around the arsenal grew into a walled fortress with large towers as protective strong points. Over the centuries the walls were gradually torn down to make way for other buildings and the city of Solothurn that grew up around the Arsenal. As warfare changed the Arsenal began to concentrate on artillery and munitions production. Small arms production and development occurred primarily at the arsenals in Neuhausen and Bern. Weapons and munitions production in Solothurn ended in the early 1940’s never to resume.

The building where the museum is located is known as the “Old Arsenal Building” and was built between 1609 and 1614. Considering that Churches were usually the largest buildings during this period the Old Arsenal was quite large consisting of four main floors accessed by a wide stone spiral staircase. There is no basement or substructure so extremely heavy objects or equipment can be placed on the ground floor. This is where the museum has positioned it’s displays of artillery that were produced in Solothurn.

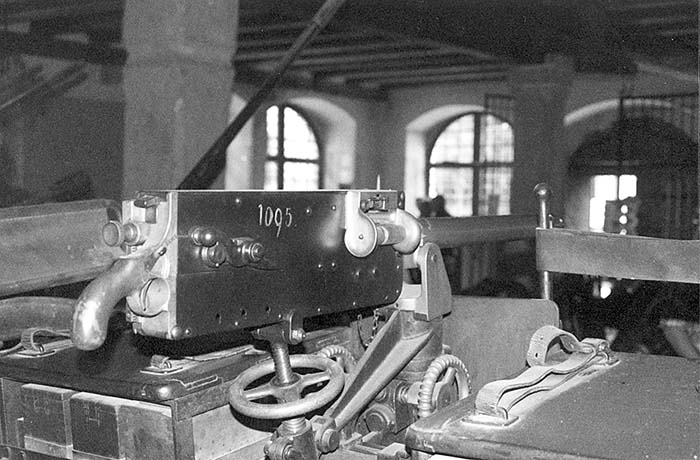

As soon as we entered through the front door of the museum I could feel a broad grin creep across my face as this was indeed an arsenal and the long trip had been worth every kilometer. In front of us was an incredible display of artillery tubes produced at Solothurn, which spanned many generations of military technology. I was surrounded by muzzle loading field pieces and mortars as well as guns produced in the 1870’s and 80’s which showed the transition to breech loading rifled cannons. Then there were the heavy guns with tracked steel wheels made in the event that WWI spilled over into Switzerland. Of special interest to me was finding a rare brass Maxim-Nordenfeldt MG 1894 machine gun mixed incongruously with field pieces and anti-aircraft guns. It was obviously placed there because it was mounted on a huge two wheeled artillery style carriage.

I’m no expert on Maxim-Nordenfeldts but a feature on it intrigued me. On the right side of the pistol grip just above the trigger was a selector lever and the word “schnell” which means “fast” in German written at the top. As I recall very early Maxim’s had the capability to increase or decrease the rate of fire at the discretion of the gunner. Unfortunately the lighting in parts of the Museum was dim at times and I couldn’t see the gun well enough to get a detailed inspection. Nevertheless this was an intriguing piece of ordnance and extremely rare.

On a raised dais across the room were four models of 20 MM “Panzerbuchse” semi-automatic anti-tank guns manufactured at Solothurn. Many of these 20 MM guns were sold to Germany prior to WWII and were in turn captured by the Allies. These are slick guns and are the man portable artillery equivalent of a Rolex watch. The Swiss were so meticulous in producing these weapons that even the small shovel issued with the gun was serial numbered to it. The four Panzerbuchsen in the exhibit were mounted by a variety of methods-bipod, tripod, and one even had small wheels and a bullet shield which made it look like a Lilliputian field piece.

One of the showpieces the Museum is very proud of is their “Organ Gun” that was made in Solothurn circa 1620. 39 muzzle-loading musket barrels were fixed in a large triangular wooden block that was held in a wheeled carriage. The barrels would be rotated to line up and fire one at a time through a single barrel, basically like a huge mutated revolver. Very interesting but I think just bundling 39 separate barrels together would have been simpler and less expensive.

Moving up the spiral staircase we entered the second floor which was filled with row after row of military rifles in plexi-glass protected racks and showcase displays on three walls. Many of the rifles in the racks were various models of Swiss Vetterli’s and Schmidt-Rubin rifles. I guess I’m like most Americans-quite frankly I’m pretty ignorant when it comes to both weapons. Let’s face it, there just aren’t many in circulation and the ammo is fairly expensive when you find it. These displays gave me a crash course in the history of both weapons. Like I didn’t know the Vetterli was made in a carbine or there were over eight models of the Schmidt-Rubin. All told, there were probably 150 Vetterli and Schmidt-Rubin rifles in pristine unfired condition.

The rest of the rifles were a potpourri of designs that spanned many nations and much time. There were racks of wheel locks, flintlocks, and percussion muskets and rifles. At one end of the room were late medieval guns made in Solothurn in the 1500’s and fired with a lit fuse. Somehow the Museum acquired six experimental semi-auto Mauser rifles three of which were serial numbered “2”, “4”, and “5”. They were very reminiscent of the early attempts Springfield Armory made to convert M1903 rifles into self loaders. All in all, one could find everything from Spencer carbines to a Johnson Automatic. A dizzying array of shoulder fired weaponry to be sure.

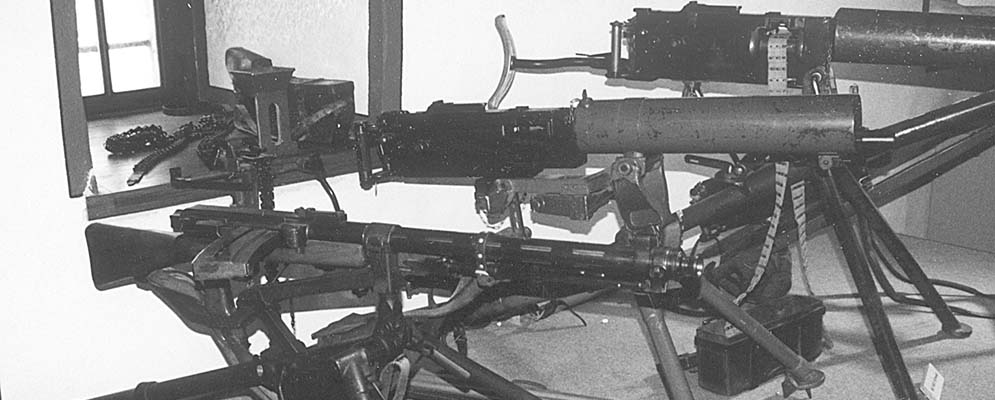

Looking beyond the rifles, I was called by the chatter of the belt fed and was lured closer by some very unusual looking automatic weapons. What caught my eye at first glance reminded me of a Dashka but it turned out to be a tripod mounted French St. Etienne M1907 heavy machine gun. Slung under the end of the barrel was an extremely unusual muzzle attachment that looked a little like a plow. Maybe it was some sort of device to help prevent dust being raised when shooting, but its true purpose was a mystery to me. The whole weapon appeared to come off the set of “Starship Troopers”.

Following the M1907 were various models of Swiss machine guns with a few French and German automatics such as an MG-42, Chauchat, Hotchkiss, and a Darne sprinkled in for good measure. The Swiss Model 1925 Light Machine Gun according to my guide was an early attempt at designing a universal automatic weapon. While it appeared to be extremely well made (like all Swiss weapons) I think it’s lack of a belt feed doomed it from it from being anything more than an automatic rifle. Actually the tripod it sat on I’d wager was heavier than the gun. The Swiss did produce genuine belt feds though and there were three different Swiss made Maxims present: 1894, 1900, and 1911 models. The most interesting of the three was the M1894. It was designed to be a man portable machine gun that had a metal pack frame attached to the muzzle end of the barrel jacket. When the gunner wished to engage a target he could unfold the frame and convert it into a firing platform.

On wall near the machine guns was a cased display that told an abbreviated history of Swiss assault rifle development. At the bottom of the case was the abysmal French M1917 St. Etienne semi-auto rifle. Chambered in 8MM Lebel, the rifle held ten shots and it was hoped the boost in firepower would help break the stalemate on the Western Front during WWI. Instead it was such a failure that all were withdrawn from front-line duty, converted to manual operation, and shipped off to Africa for native colonial troops. Fortunately the next rifle in the display was the excellent StG 44 which greatly influenced Swiss and other European weapons designers. The next rifles in the showcase though were all home grown Swiss creations.

Shown above the St. Etienne and StG 44 was the AM-55 a forerunner of the StG-57 and chambered in 7.5 X 55 MM Swiss. Directly atop the AM 55 was the StG-57 which was the mainstay of the Swiss army for years until replaced by the SIG 550. Having handled a few StG-57’s in the past this is one rifle I really wouldn’t have wanted to pack through the Swiss Alps. Loaded, it weighs in at twelve pounds and the balance is atrocious. My Swiss friends with tongue in cheek call it their “light machine gun”. Of course being a Swiss firearm it is supremely accurate and very well made.

Beginning in the last half of the 1960’s the Swiss started to experiment with infantry rifles that were chambered in smaller calibers and were more portable than the StG-57. Displayed was a SIG 530-1 produced in 1967, and two models of the StG 541 made in the early 80’s. All three were in 5.56 MM and unlike the StG-57 none used the delayed roller lock system but rather a conventional gas driven operating rod and rotating bolt. For all lovers of the SIG AMT there was a SIG 510-6 with green plastic furniture chambered in 7.5 Swiss.

The final rifle in the exhibit was an experimental StG-22 rifle in 6.45 X 55 MM made at the arsenal in Bern. My Swiss guide actually owns one of these rifles and allowed me to field strip it in his home. The 6.45 X 55 cartridge was created by necking down the standard 7.5 Swiss case to 6.45 MM. It uses an operating rod connected to a bolt carrier which holds a rather smallish dual lugged rotating bolt. My Swiss friend thinks it’s a terrible design and I defer to his expertise when it comes to Swiss military rifles. Ammunition is very scarce and an ersatz solution is found by reloading the spent cases utilizing 6.5 MM bullets. My friend acquired this rifle directly from the Swiss Arsenal at Bern. From time to time the Arsenal releases prototypes and experimental rifles which they feel are no longer needed. Since my friend is a collector he bought one as a piece of Swiss history. This intrigued me. Could you imagine the collector stampede if the Springfield Armory National Historical Site decided to sell some of their T20E2’s or if Anniston Arsenal put Stoner 63’s up for sale?

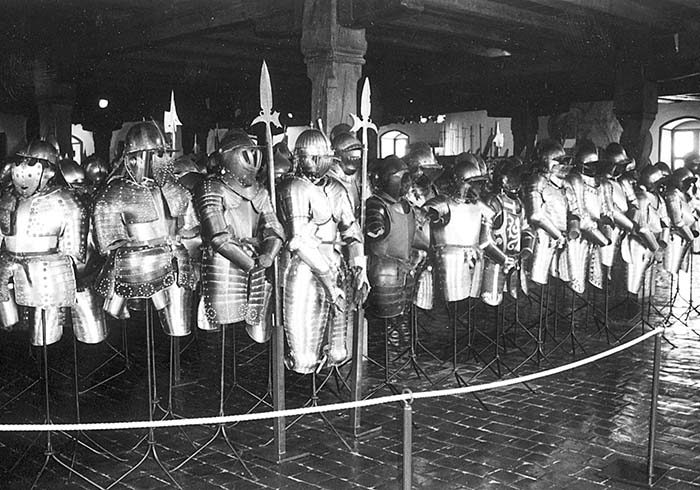

Moving to the third floor (second floor to Europeans) I exited the staircase and was stopped in my tracks by what seemed an endless collection of Medieval armour which filled most of the floor space. Standing before me were over 400 sets of armour. Like most of the contents of the Museum they were in outstanding condition-no rust, dents, or scratches. At one time the Arsenal contained 1500 sets but 900 were sold in 1833 to buy new artillery pieces. To complement the armour suits was a fine selection of halberds, billhooks, and the weapon which literally drove fear into and through the hearts of European armies-the dreaded Swiss pike. The condition of these weapons matched that of the armour.

The top floor was filled with exhibits populated by mannequins wearing the various uniforms of the Swiss military from the beginning of the Swiss Confederation to present day. Unfortunately half the floor was closed for remodeling.

If you are in Europe the Old Arsenal Museum is well worth the trip. I have never been in a museum that had weapons in better condition. Most of this I believe is due to the fact that Switzerland, unlike its neighbors, hasn’t had to fight a war in hundreds of years so their weapons haven’t become used, abused, lost, or looted. The only curious thing about the Old Arsenal Museum was that it contained no submachine guns. I didn’t notice this at the time as I was so overwhelmed by everything else though. From May-October the Museum is open from 10 AM-1200 noon, and 2 PM-5 PM Tuesday through Sunday. From November-April it is open Tuesday-Friday 2 PM-5 PM, and Saturday/Sunday 10 AM-1200 noon, and 2 PM-5 PM. Admission is 5 Swiss Francs and there is a donation box. The Museum is located at Zeughausplatz 1, 4500 Solothurn, Switzerland, phone (41) 32 623 35 28

I would like to give special thanks to Herr Thomas Kuhne who guided me through the Old Arsenal Museum and assisted me in the preparation of this article.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V3N4 (January 2000) |