by Jim Frigiola

During World War II there was no special ammunition issued for use by snipers. Since the US issue sniper rifles of the period were nothing more than a service rifle fitted with a telescope, the sniper in the field was left to his own resourcefulness to select ammunition. In his book Shots Fired in Anger, LtCol John George recounts taking his personal Pre-War Winchester Model 70 into combat with the Japanese in the islands of the Pacific. LtCol George states that he selected a good shooting lot of .30 caliber M2 Ball ammunition made at the Denver Ordnance Plant. It is not likely that this ammunition was capable of producing groups as small as 2 minutes of angle (MOA) in his rifle.

Snipers by necessity pay particularly close attention to the quality and care of their rifle equipment and ammunition. For the most part only the most accurate match-grade ammunition is selected and fired through the sniper’s weapon. The most accurate standard issue ammo is, of course, match ammunition intended for competitive marksmanship use. The demands of wartime logistics, however, are characterized by large volumes of ordinary service-grade product, where abundance takes priority over quality. While very good Caliber .30 M1 National Match Ball ammunition was made during the 1930s, the US Military made no match-grade ammo during the 1940s. Standard issue match ammo did not appear again until the late 1950s when the Caliber .30 M72 Match round was standardized about the same time that 7.62x51mm NATO rifles were adopted.

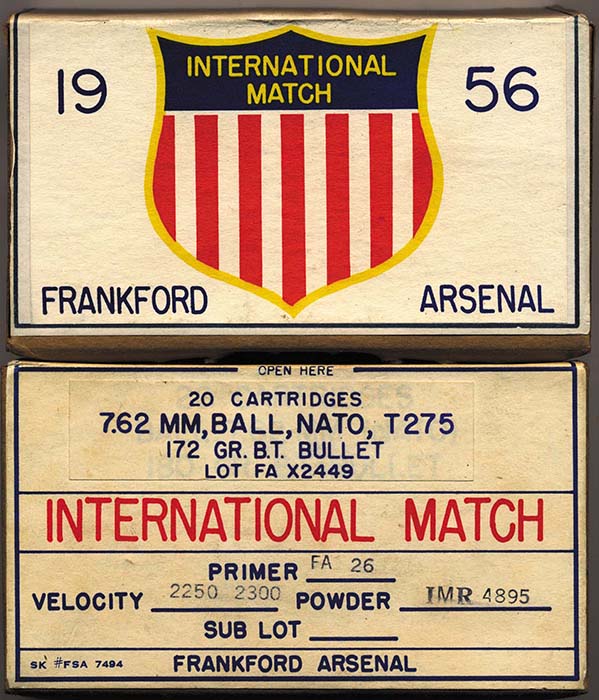

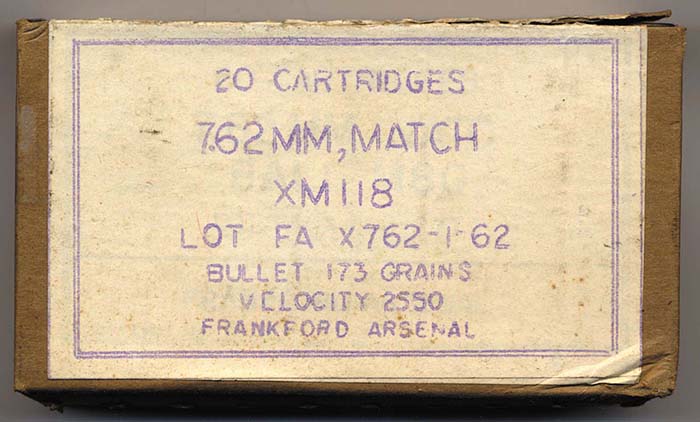

The earliest work to develop a 7.62x51mm NATO match round started in the mid 1950s at Frankford Arsenal. The first version was designated T275 and was an International Match load. No special bullet tailored to the 12-inch twist rate of 7.62mm barrels was used in the T275 cartridge. Instead it was loaded with the same 173-grain bullet as the Cal .30 M72 Match round. This bullet was essentially the 1926-vintage caliber .30 M1 Ball bullet without the knurled cannelure. Accuracy performance specifications for the T275 called for a maximum mean radius of 3.5 inches at 600 yards when fired from a Mann barrel in a machine rest.

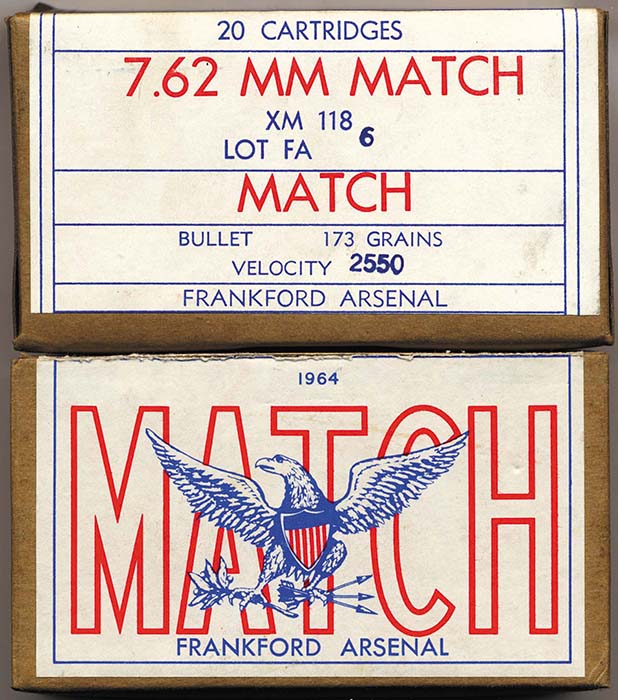

The T275 cartridge went through several design and load development iterations based on feedback from competitive rifle marksmen from AMU, Ft Benning, Georgia. The final version, the T275E4, was re-designated XM118 as work continued at Frankford Arsenal. Standardization of this round as the M118 Match cartridge occurred in the early 1960s and production was transferred to the Lake City Army Ammunition Plant in Independence, MO. During the 1960s and 1970s, the round became more accurate as Lake City was able to refine the manufacturing process and product performance. The accuracy specifications did not change over time but average lots of M118 Match showed 600-yard accuracy with mean radii around 2.4 inches. A few very exceptional lots were below 2.0 inches.

In the mid 1960s LtCol David Parsons was commanding officer at Lake City Army Ammunition Plant. Parsons was himself a distinguished rifleman and handloader. Under his leadership and with his personal attention, some of the most accurate M72 and M118 Match ammunition was produced. The cartridges were packed in clean white boxes bearing the colorful Match Eagle on the backside. When a rifleman broke open one of these distinctive white boxes he knew he had the best quality cartridges made in America. During this period Lake City made up special chrome-plated .30 caliber and 7.62x51mm dummy match cartridges, which were issued as souvenirs – one to each shooter competing in the National Matches at Camp Perry. These handsome chrome dummies are now prized as collector’s items.

The need for precision high-accuracy ammunition was recognized in the commercial sector as well. Federal Cartridge Company, working closely with Marines at Quantico, developed their famous “308M” load using superbly accurate Sierra 168-grain International Match bullets. These loads became popular with law enforcement SWAT Teams as well as service rifle shooters.

Interservice and National Match rifle competition being what it was at the time drove Army and Marine Corps shooters to seek even more accurate loads. By 1980 it was known that the Sierra 168-grain International Match bullet was significantly more accurate in M14 Match rifles and gave top shooters a real competitive edge when firing the National Match Course at 200, 300 and 600 yards. Commercially loaded Federal Cartridge Co ammunition was highly prized but often not available to military riflemen. Field users developed the practice of removing the 173-grain bullet from Lake City M118 ammo and replacing it with the 168-grain Sierra. Such ammunition, while not official issue, was authorized for competition at Camp Perry and was known as “Mexican Match” ammo.

Army ammunition product managers eventually heard the wake up call. In 1981 Lake City began loading a new 7.62x51mm Match cartridge using the 168-grain Sierra bullet. This round was first designated XM852 and was soon standardized as the M852. It quickly replaced the M118 as the preferred match round for competitive marksmanship use. Since the Sierra 168-grain projectile was labeled as a hollow point boattail (HPBT) bullet it was prohibited for service use by snipers against personnel. Throughout its production history cartons containing M852 ammunition were conspicuously marked “Not For Combat Use”. So cautious about this sensitive legal issue were the Army product managers that they also required that cases used for M852 rounds be further identified by a knurled cannelure near the extractor groove. This feature allowed fired cases to be identified as having launched an HPBT bullet. As could be expected, the case body knurl on M852 brass was very unpopular with handloaders because of a real or perceived reduction of case life when subjected to repeated cycles of resizing, reloading and firing.

Match Box Graphics -The distinctive graphics used for Match ammunition boxes was seen to degrade over the years, as did the accuracy performance. One would guess that these changes were due to a desire to seek cost savings in manufacturing operations. Shown here is a Frankford Arsenal label at the top. The Lake City box in the center shows a little less ornate eagle. Eventually, as seen on the bottom box, the eagle disappeared all together from boxes of M852 ammunition.

M852 Match ammunition did replace M118 Match ammunition in the field as the standard round for marksmanship competition. However, military snipers, being required to use only FMJ ammunition were left with only the less accurate M118 for training and combat. Production of M118 at Lake City did continue for snipers but the cartridge was downgraded by a name change from M118 MATCH to M118 Special Ball. No longer packed in clean white Match cartons bearing the distinctive Match Eagle the Special Ball loads were issued in plain brown paper boxes. At the same time the prestigious MATCH notation was deleted from the headstamp of M118 Special Ball ammunition. The new cases looked the same as M80 Ball cases and even had crimped in primers. Further, to the chagrin of accuracy conscious riflemen, performance of M118 Special ball ammo deteriorated noticeably. Cartridge accuracy specifications remained unchanged from the original 3.5-inch mean radius at 600 yards, but newly loaded rounds were issued which barely met this loose requirement. Gone were the days when “white box” M118 Match ammo was made with pride and every lot far exceeded the accuracy requirement by a significant margin.

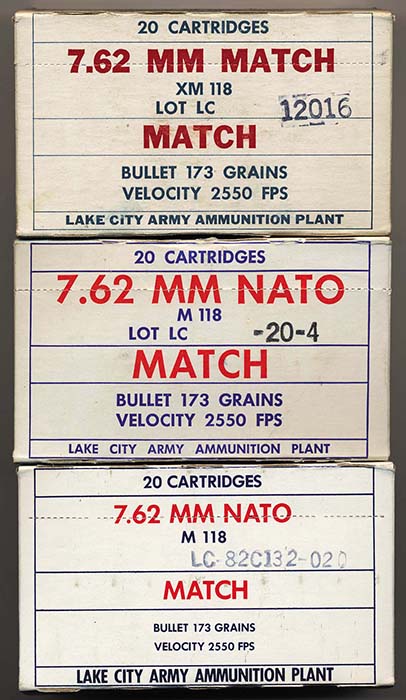

White Box M118 Match Ammunition – Some of the most accurate 7.62 Match ammunition came in these distinctive white boxes. Shown here are examples of Lake City production lots from the 1960’s, 1970’s and early 1980’s. These white boxes became highly coveted by accuracy conscious riflemen after they were superseded by brown box M118 Special Ball ammo.

An interesting thing happened in 1990 when US Army lawyer Hays Parks, a technically astute former Marine, conducted a legal review on behalf of the Judge Advocate General of the Army. Parks looked at the issue of whether combat use of Sierra HPBT match bullets violated any international agreements pertaining to weapons of war. Given the fact that the most accurate bullets do have an open tip, it was determined that these bullets were not true hollow points, per se, and that they were not designed to mushroom upon impact or cause undue suffering. Indeed, testing showed that Sierra match bullets do not behave at all like hollow point expanding bullets when fired into ballistic gelatin. From a technical standpoint it was clear that the open tip of such bullets was a design feature selected for aerodynamic reasons and served the purpose of accuracy improvement rather than having any excessive wounding effect. The Army JAG issued a lengthy legal memorandum, which states that the military use of open tip bullets does not violate any treaty obligations of the United States. The Parks memorandum was endorsed by the military services and legally authorized such ammunition as the M852 Match cartridge for combat use. Nevertheless, the ammunition usage policy changes allowed by this important document were never fully realized nor enacted in general practice. Cartons in which M852 cartridges were packed continued to bear the “Not For Combat Use” warning.

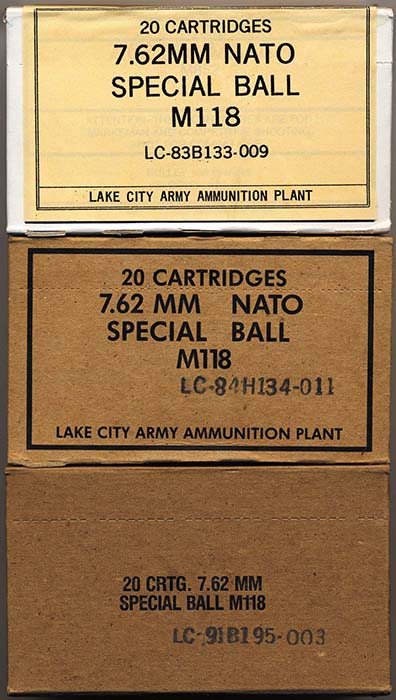

173 gr Special Ball Ammo – The M118 Match round was downgraded and redesignated as Special Ball in 1983 after the adoption of M852 Match ammunition as the preferred round for marksmanship competion. M118 Special Ball was packed in brown boxes when it first appeared. But even these brown boxes seem to have suffered cost cutting measures. Examples from the final production lots don’t even have a border around the label. Nor do they indicate the source of manufacture.

The Army and Marine Corps took different paths in the development of sniper rifles. From the 1960s the standard Army issue sniper rifle was the M21. This was essentially a match-grade M14 rifle with a suitable scope mounted. It gave respectable accuracy when newly assembled but was difficult to maintain. The M21 was eventually replaced by the more dependable M24 rifle. M24s were of commercial design using a Remington Model 700 long action.

The Marine Corps however, always preferred bolt-action rifles. In the 1960s in Vietnam Marine snipers used Winchester Model 70 rifles. These were eventually replaced by the more refined Marine Corps unique M40 sniper rifle built by Remington as a special order short action Model 700 rifle. It was fitted with a Redfield 3X9 variable-power scope. Currently fielded M40A1 rifles are very rugged, highly accurate and are equipped with an excellent 10X Unertl scope. The M40A1’s are soon to be replaced by the M40A3, a new generation rifle having more bells and whistles.

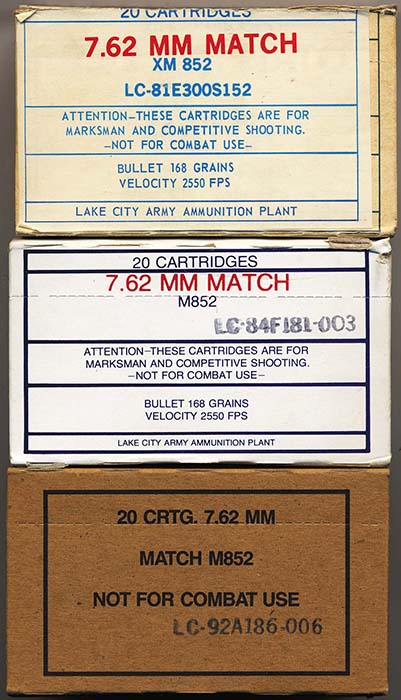

The Excellent M852 Match Ammunition – The XM852 Match round using the highly accurate 168 gr Sierra Matchking bullet first appeared in 1981. These excellent rounds were the preferred choice of expert and master class riflemen for a decade or more. As can be seen from these sequential box labels M852 ammo always came with a restrictive warning that these were “Not For Combat Use”. Military snipers were left with only M118 Special Ball for business use.

The special reticule of the Marine Corps Unertl scope allowed snipers to achieve hits at ranges out to 800 and 1000 yards. However, these optical aids were developed based on the known ballistic trajectory of old M118 “white box” Match ammunition. The new M118 Special Ball ammo in brown boxes was found to be seriously deficient in shot placement using the Unertl reticule. In addition to being less accurate at short ranges the Special Ball ammo showed an unacceptable mismatch in trajectory at very long range.

The 168-grain Sierra Matchking bullet was originally designed for 300-meter International competition. Indeed, when first introduced this bullet was labeled “International” but is now simply known as a Matchking. M852 ammunition using this bullet does, however, give excellent accuracy out to 600 yards. But at ranges beyond 600 yards the 168-grain bullet begins to falter. At 1,000 yards the remaining velocity drops below subsonic levels and stability becomes poor. The older 173-grain bullet of the M118, although not as accurate, did maintain its flight stability very well beyond 600 yards.

While the Army product managers were quite satisfied that the M118 Special Ball was performing within official specifications, the Marine Corps, having made a considerable investment in the Unertl scope, wanted an improved cartridge that would meet their training and operational needs at very long ranges. They decided to seek a solution on their own without support from other services.

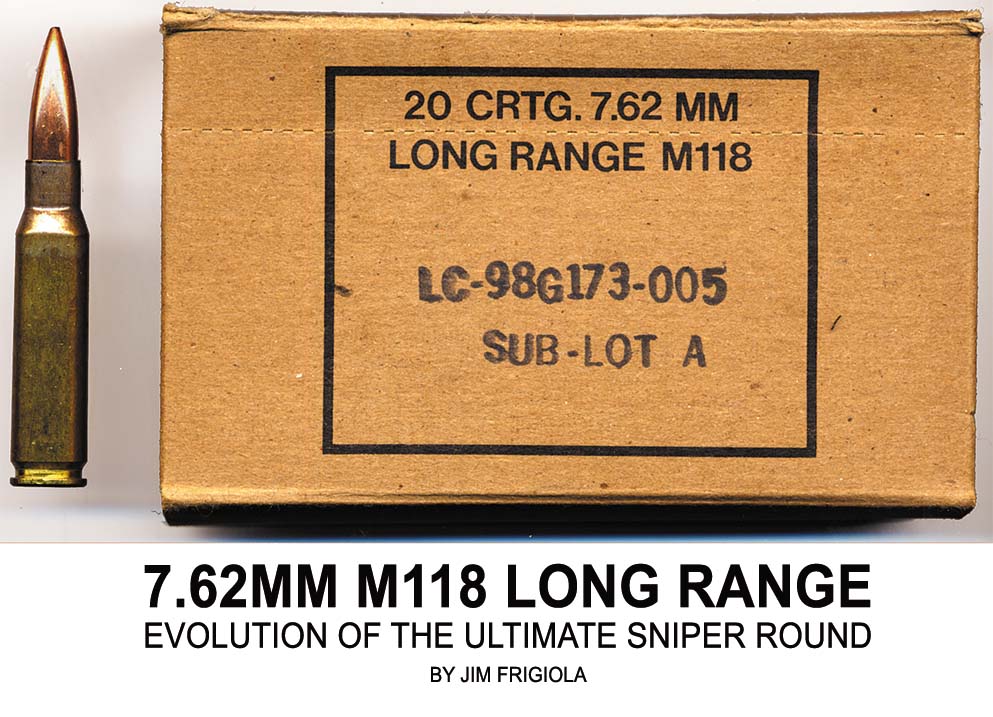

A project was started in the mid 1990’s to identify a new bullet suitable for long-range use in 7.62x51mm sniper rifles. Engineers at Lake City and Sierra took a look at the USMC unique requirements and evaluated a number of candidate bullets and other cartridge improvements. An accuracy requirement calling for MOA dispersion measured at 1,000 yards was established. After extensive testing a new 175-grain HPBT bullet having a 9-degree boattail emerged from Sierra. This new Mathking bullet remains supersonic at 1,000 yards and has proved capable of meeting the extraordinary long-range accuracy requirement. This load came to be the M118 Long Range cartridge. The letters LR appear on the headstamp to serve as visual identification. A new logistic code of AA11 was assigned to identify this round as different from earlier M118 ammunition.

Thus, the M118 cartridge has entered a third phase of its production history, having been originally designated MATCH, then Special Ball, and now Long Range. No other small arms cartridge has ever been redesigned and reengineered so often over so many decades. Production of M852 Match ammunition has been discontinued since the new M118 Long Range round is now the preferred ammunition for 7.62x51mm rifle competition. In addition, as further tribute to the success of this USMC initiative, we note that Navy and Army snipers have also adopted it for operational and combat use.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V7N2 (November 2003) |