By Steve Hyde

Back in the 1950’s, when people were still amazed at things like supersonic flight and ballistic missiles, newer and faster aircraft seemed to be introduced almost weekly. The new 1,500 mph Lockheed F-104A Starfighter didn’t disappoint anyone as the U.S. Air Force put the world’s fastest jet through its paces at its first public flight on March 5, 1956. Gathered to watch the spectacle were over 200 reporters, government officials and other curious onlookers assembled at the Air Force’s production test facility at Edwards Air Force Base near Palmdale, California. When the show was finally over and the crowd inspected the plane on the ground, many noticed a rather curious bulge in the front left side of the fuselage. Several speculated openly that it covered the Air Force’s mysterious new “supergun”, a marvelous new machine gun that had been rumored about for the past two years but remained shrouded in secrecy. The Air Force, of course, would say nothing.

But there had been some hints dropped. A few months before the F-104’s flight, Lt. General Donald L. Putt made a speech during a meeting of the Aero Club of Washington. Gen. Putt, at that time head of Air Force armaments development, stated that the standard .50 caliber Browning aircraft machine gun with its 850 rpm cyclic rate had become outclassed in the new jet age. Replacing it was the M39 20 mm automatic cannon, a new weapon with a cyclic rate of about 1,700 rpm. And the M39, he continued, would soon be replaced by a still newer gun, a 20 mm gun that could achieve almost 7,000 rpm!

This and other vague references to the new “supergun” kept the rumors going strong until the Starfighter was first shown to the public. Then the desire for information became so strong that, shortly after the fighter’s flight, the Pentagon finally acknowledged that a new 20 mm machine gun was in the final stages of development, with regular production expected to begin later in the year. The gun was a joint venture involving the U.S. Army Ordnance Dept., the Air Force and the General Electric Co. of Schenectady, New York. The Pentagon had even given the project its own code name—”Project Vulcan”!

The story of “Project Vulcan” goes back to 1945 and a research effort being conducted between the then Army Air Force and the U.S. Army Ordnance Department’s Research and Development Service, Small Arms Branch. In command of this branch was Colonel Rene R. Studler and under his command were two officers, Cleves “Doc” Howell and Melvin M. Johnson, Jr. (of Johnson rifle and LMG fame). While traveling to Waterbury, Connecticut to consult with yet another machine gun contractor having belt-link problems, Howell suggested to Johnson the idea that the old Gatling guns should be tested with an external motor attached for possible aircraft applications. Johnson replied that he was not particularly pleased with the prospect of dealing with the belt-link problems of a high-speed Gatling. But Howell eventually persuaded Johnson of the validity of the concept and both agreed that a proposal should be brought before Col. Studler.

The colonel listened to the young officers’ proposal intently, and then granted them permission to do a “feasibility study” of the idea. Backed by Studler, Army Ordnance granted Johnson Automatics, Inc. (Melvin Johnson’s own company) a small contract to do research with antique Gatling guns that were in the collection of the Ordnance Museum at Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland. The tests were conducted in late 1945 at Johnson Automatics’ private test range in Cumberland, Rhode Island. Johnson himself wanted to test one of the later versions of the Gatling, a caliber .30-06 or .30-40 Krag model from the period 1896 to 1910. Unfortunately none could be found at the time and Johnson had to settle for a .45-70 model 1886 Gatling with 10 barrels and a 103-round Accles feed drum. Dr. Richard Jordan Gatling, inventor of the original gun, had conducted a few tests himself with a powered gun in 1896, but by then the Gatling was being overshadowed by the self-powered designs of Browning, Maxim and others. Nothing came of those early experiments, and Dr. Gatling died in 1903.

Two tests were conducted, one at approximately 4,000 rpm and another at 5,500 rpm, each with the Accles drum loaded with only fifty rounds so that the gun mechanism could build up speed before firing. In spite of the clouds of smoke created by the use of original black-powder ammunition, Johnson’s tests were a great success. A few more bursts were fired and the old Gatling performed amazingly until an extractor failure brought the tests to an end. Johnson immediately submitted his findings to the Ordnance Dept. along with some recommendations for making a plausible belt-fed weapon. Ordnance was impressed enough with the findings that on January 18, 1946, only a couple of months after Johnson’s tests, the Dept. awarded the General Electric Company a contract to further study the idea. By June G.E. had a contract to develop a practical powered, belt-fed Gatling. Johnson’s original test gun was bought by Winchester in 1949 and eventually ended up in the museum of the Olin Mathieson Chemical Corporation.

The Air Force, which was providing most of the funding for the project, laid down the initial specifications for the gun. It wanted 5,000 rpm, a caliber of about .60, a 60-inch barrel length with the entire gun being no longer than 80 inches, and five barrels. It also wanted the gun to be easy and quick to maintain and reliable at high speeds, altitudes and extremes in temperature. G.E. engineers went to work and by April 1949 they had a prototype that could achieve 2,500 rpm reliably. By June 1950 an improved prototype had reached 5,000 rpm, and by September it reached 6,000. Further testing was conducted at Aberdeen Proving Ground and at the Springfield Armory in Massachusetts. Four different versions were tested, and in May 1952 seven prototypes shot 75,000 rounds without a jam.

Things looked promising for the motorized Gatling, but it was not without competition. In 1945, as Hitler’s Third Reich crumbled, the Allies overran the Mauser facilities at Oberndorf and found that the Germans had produced a prototype gas-operated, high-speed cannon using a revolving drum to feed a single barrel. After the war ended, a joint project between Army Ordnance, the Air Force and the Ford Motor Company produced the M39 automatic cannon, a weapon very similar to the original Mauser. Development proceeded quickly and this weapon officially replaced the Air Force’s M3 Browning in time to see action at the very end of the Korean War, in MIG Alley in 1953. Eight F-86F Sabrejet fighters were equipped with the new guns and in only a few days destroyed 9 MIGs and damaged 12 more. The gun became standard equipment in all Air Force fighters until the introduction of the Starfighter in 1956, and was primarily produced by the Pontiac Motor Division of General Motors. But even though the MIG Alley encounters demonstrated the validity of the high-rpm aircraft gun, the capability of the M39 was limited by its single barrel and even it couldn’t keep up for long.

Fortunately, progress on the new Gatling was made at a rapid pace. By mid-1952 three different versions were still being considered. There was the .60-cal. T-45 (also called Model “A”), the 27 mm T-150 (Model “B”), and the 20 mm T-171 (Model “C”). After additional trials at Springfield Armory the T-45 and T-150 were dropped from consideration and the T-171, now being referred to as the “Vulcan” gun after the project code-name, was stepped up to the pre-production phase. In August 1952 G.E. produced 27 T-171 six-barreled guns for extended Air Force trials at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, and after successfully completing these trials General Electric was awarded a contract to begin pilot production of the gun at their Schenectady, New York plant in 1954.

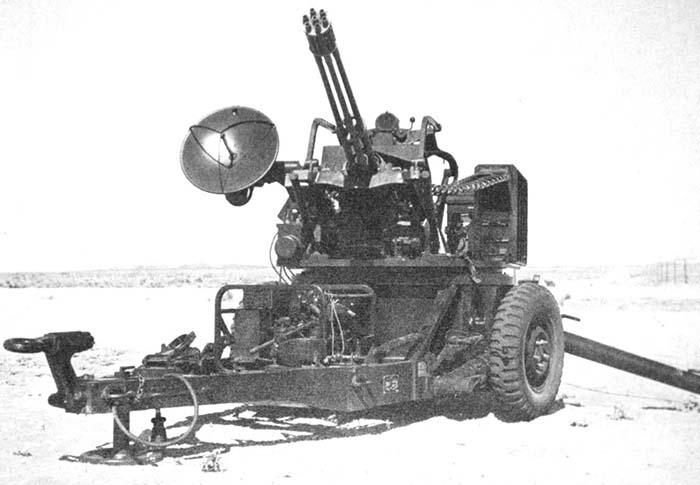

The “Vulcan” was finally shown to the public at Aberdeen Proving Ground on August 28, 1956 after having been adopted officially by the Air Force earlier in the year as the M61. General Electric was awarded a 7-million dollar contract to begin full production late that year at Schenectady, and later production was moved to the company’s Aircraft Equipment Division plant in Burlington, Vermont. Two versions, one with electric motors and one with hydraulic motors, were produced to satisfy the requirements of the Air Force’s two largest aircraft contractors, Lockheed and Republic. A year after the T-171 was adopted, a larger 30 mm version dubbed the T-212 was introduced. The T-212 was originally designed to fire high-explosive shells and was to be used on heavily armored targets against which the 20 mm standard armor-piercing rounds were ineffective. But it was not until 1973 that the Pentagon would find a use for the big 30 mm, when on June 21 of that year General Electric was awarded a contract to produce the GAU-8A “Avenger”, an updated T-212, for use in the new Fairchild-Republic A-10 “Thunderbolt” (aka “Warthog”) close-air support aircraft.

It was never entirely smooth sailing for the Vulcan when it came time to decide the Defense Department’s budget. Major emphasis at that time was placed on guided missile development, and Air Force small arms development took a back seat. Several times “Project Vulcan” and other projects such as the M39 came close to being cut out altogether, and in fact all Air Force small arms programs were cut entirely in 1957 and did not resume again until early in the Vietnam War. But Vietnam was to be the coming of age for the Vulcan concept both in the air and on the ground, and would see the extensive use of both the Vulcan and its diminutive but famous offspring, the “Machine Gun, Aircraft, GAU-2/A”, more commonly known as the “Minigun”.

Many people believe that the Minigun was conceived and developed expressly for use in the Vietnam War, but that is not entirely true. A rifle-caliber gun for use in direct tactical support of ground troops was part of the overall concept from the start, and the “mini-Vulcan” gun was actually conceived as part of the original 1946 contract that spawned the T-171 and T-212. Development of the 7.62 mm version was begun in 1957 immediately after the U.S. Army adopted the T-44 (M-14) rifle and its 7.62mm x 51mm NATO cartridge in May of that year, and G.E. had prototype guns and universally mountable “gun pod” systems ready by mid-1958. The gun itself, designated by G.E. as the model GAU-2/A, was originally designed to be housed in its own self-contained “pod”, or enclosure, designated SUU-11A/A. This pod held the gun, its feed mechanism, fire controls and ammunition, and was intended to be a simple add-on assembly that could be mounted on the exterior of any subsonic aircraft. Later, in 1963, G.E. would also offer the Vulcan in its own self-contained bolt-on unit, nicknamed “VULPOD”, for use on close-air support variants of the F-100, the F-104 and F-4C fighters. But, like the T-212, the Pentagon simply didn’t have a use for the Minigun at that time. It would not be until mid-1963 and the Air Force’s search for a weapon system for their fledgling gunship program, that G.E.’s old 1958 prototypes would be dusted off and further developed in the Weapons Laboratory of Detachment 4, Aeronautical Systems Division of the Air Force Systems Command at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. The rest, as they say, is history.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V3N1 (October 1999) |