By Paul Evancoe

Triggers are one of the most misunderstood parts of a firearm and for good reason—the numerous terms associated with them: two-stage, single-stage, double trigger, double-set, double-action, single-action, pull-release trigger, safe-action trigger, trigger creep, length of pull, break weight, trigger slap, reset, custom geometry, sears, hammers, disconnectors, direct replacement, modular replacement, etc. What does it all mean? (Please note that triggers used on fully automatic weapons will not be addressed in this article.)

Many shooters classify the trigger(s) on their firearm(s) as either good or bad. We tend to categorize a hard-pulling trigger in the “bad” category, while easily pulled (light-pulling) triggers are seen as “good.” However, the delta between good and bad contains a variety of subtle attributes not generally understood. A lighter, easier to pull/manipulate trigger can make a huge difference for the competition shooter or tactical sniper, when a single shot determines the critical difference, but it may not be suitable or safe for sporting purposes.

Single-Stage vs. Two-Stage

Most of us have no idea if we’re pulling a single-stage or two-stage trigger. Since two sounds better than single, and we are conditioned to believe more is always better, we assume a two-stage trigger is best for our shooting purpose. That assumption is simply wrong. So, what’s the difference?

A two-stage trigger (also called a double-stage trigger) has two stages of operation (or steps) to its break (point of release). The break is the point of the trigger pull when the sear releases the hammer, or the striker, to fire a shot. In a two-stage trigger, the first stage provides a set amount of free trigger movement under spring tension, and that movement ends in a distinct stop. At the stop, continued finger pressure must be applied to the trigger to eventually release (break) the sear engagement and fire the shot. The trigger pull is a distinct two-stage process. Once the gun fires, the trigger return distance (or trigger “swing distance”) to reset is notably lengthy in most two-stage triggers.

Single-stage triggers are the oldest design of all triggers as well as the most widely used. A single-stage trigger doesn’t have the initial spring-tensioned movement to a predictable stop. Its pull essentially starts at the second stage of trigger pull (at the stop), and that’s how it differs from a two-stage trigger. We’ll discuss trigger break weight in moment.

Which is better—a single-stage or two-stage trigger? Safety is the primary reason many military rifles use two-stage triggers. The AR-10 and AR-15 are the exception because they both use a hard-pulling, 6-to 10-pound (factory-set), single-stage trigger. It’s designed to be hard pulling out-of-the-box for safety purposes (low manufacturing cost is another driving factor for the AR-style, single-stage trigger). Most sporting rifles and shotguns have factory-set single-stage triggers. Many target and competition rifles have double-stage (two-stage) triggers. A double-stage trigger is thought to be safer because the trigger has a separate, distinct and predictable movement (travel) before it comes to a stop; it then requires additional trigger pressure for the final break/release. Thus, a shooter can come in and out of a shot with a higher degree of safety.

Double-Set vs. Double-Stage Triggers

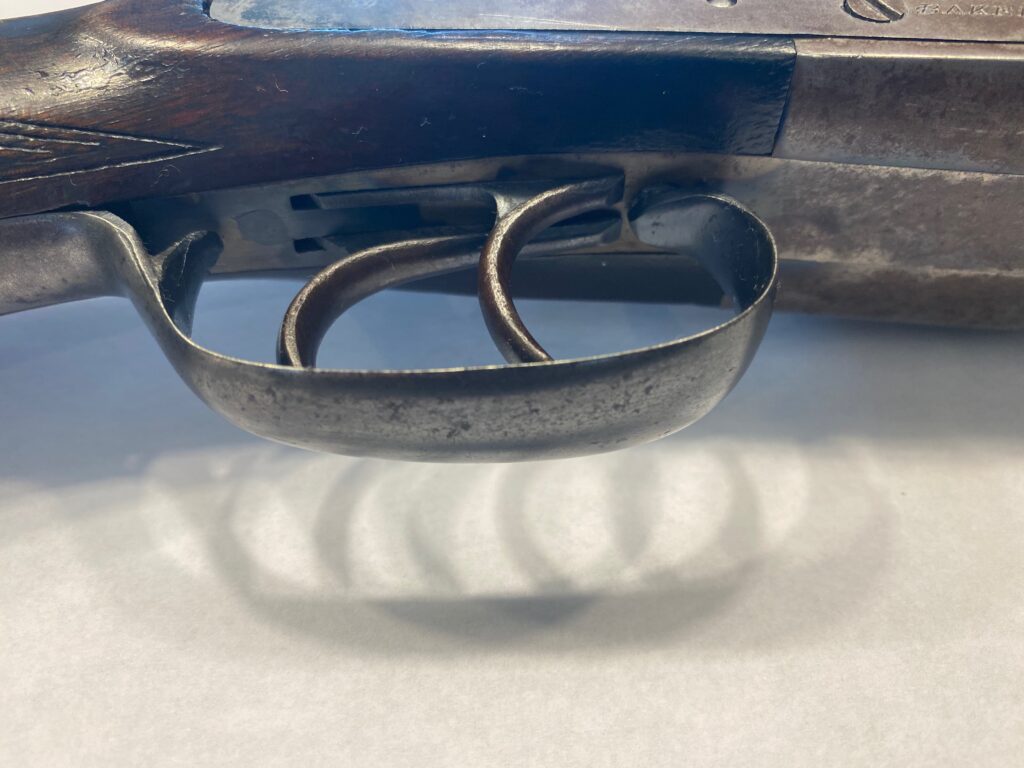

What’s the difference between double-set and double-stage triggers? To be sure, double-set triggers are not the same as double-stage triggers. Double-set triggers were primarily used in the 1800s on early black powder rifles and muzzle loading pistols, both flintlock and cap-lock, to improve long-range accuracy and safety. A double-set trigger is easily identified on these early firearms because the gun has two in-line triggers (not two side-by-side triggers—also called double triggers).

After the gun’s external hammer is manually cocked rearward into the full cock firing position and the target aim is acquired, the forward set trigger is pulled. This trigger sets the rear trigger, which is a single-stage, low break-weight (“hair”) trigger. The forward set trigger is a hard pulling trigger usually requiring around 8 to 10 pounds of pull. The trigger set can easily be felt as the pull stops and an audible click sounds. The trigger finger is then moved from the forward set trigger to the rear trigger to fire the gun. Now set, the rear trigger is a single-stage hair trigger requiring very little release pressure (low break weight) to release the hammer that subsequently fires the gun.

The set trigger was intended to be a hard-pulling trigger because these early guns did not have safeties. Therefore, carrying them with the hammer in the fully cocked, ready-fire position was highly unsafe. The double-set trigger both increased the margin of safety and increased accuracy.

There’s another confusing trigger to understand: the dual trigger. A dual-trigger configuration is most commonly found on older double-barrel (side-by-side barrel configuration) shotguns. They’re easily identified because each barrel has its own dedicated trigger, and the two triggers are configured in-line much like the double-set triggers previously discussed. Dual triggers are themselves each single-stage triggers independent of one another. The gun is fired by pulling the first trigger (it’s the shooter’s preference which trigger to pull first) and moving the finger from the first trigger to the second trigger. Most double-barrel shotguns employ different size chokes in their two barrels. Most shooters will fire the barrel choked to the widest shot pattern first at a close-moving target and then fire the more tightly choked barrel second at the longer distanced target. The double trigger provides the shooter an instant barrel (choke and shot shell load) selection depending on the range of the target.

Double triggers have been almost completely phased out with the advent of the single-selective trigger now used on modern side-by-side, double-barrel and over/under barrel shotguns. This single-stage trigger has a selector switch usually located atop the tang behind the top lever. The selector switch allows the shooter to quickly select which barrel he wants to fire first. Many single-selective triggers use either an inertial cocking mechanism to cock the second striker as a safety feature, or a spring-operated selector that automatically switches the trigger over to fire the second barrel upon firing the first barrel. Single-selective triggers have been refined in a wide variety of break weights and configurations for competition and sporting purposes.

Single-action and double-action triggers also provide a level of confusion. The term single-action was never used until the mid-19th century when firearms with “double-action” triggers were invented. Before that, all triggers were single-action, e.g., matchlocks, flintlocks, muskets, cap and ball pistols, etc.

A single-action trigger is the most mechanically uncomplicated and simple operating of all trigger designs. It is nothing more than a simple single-stage trigger that requires the hammer of the gun be manually cocked for each shot before the gun can be fired. A prime example of this type of trigger can be found on the Old West’s Colt Peacemaker-style revolvers and the cap and ball black powder revolvers that preceded it. The revolver’s hammer must be manually cocked back, resetting the trigger, before each shot. Pulling the trigger with the hammer down cannot fire the gun.

Double-action triggers were most often used in revolvers, but today there are a number of semiautomatic (self-loading) handguns that employ them as well. The easiest way to understand a double-action trigger is by using the example of a child’s toy cowboy cap pistol. When the trigger is pulled, the trigger pull cocks the revolver’s hammer back (it works the same way in a self-loading pistol). When the trigger reaches its furthest rearward position during pull, the hammer releases, and the gun fires. Each trigger pull (in a double-action revolver) results in firing.

In the self-loading semiautomatic, a double-action trigger works similar to the revolver. The trigger is pulled through the first shot (same as a revolver), but once the first shot is fired, the slide’s backstroke ejects the spent cartridge, resets the trigger and cocks the hammer (or striker) in preparation for the next shot. The slide’s forward stroke loads (chambers) a fresh round, and the gun goes into battery. The next shot is ready. In this case, the trigger essentially becomes a double-stage trigger for every shot following the first shot.

This is where “trigger travel” comes into play. Once a double-action trigger fires the first shot on a semiautomatic gun, the trigger has a degree of travel (free movement) to its stop point (for each succeeding shot) where pulling it further, releases the trigger sear and the gun fires. Some shooters refer to this free movement as “trigger slop” because the pull feels sloppy, but it’s really a matter of training and individual shooter preference.

GLOCK

GLOCK’s popular SAFE ACTION® System trigger is found on all GLOCK pistols (since 1983) and is now in use on numerous other modern handguns and some rifles. Walther’s “quick-action” trigger and some other pistol manufacturers offer very similar triggers. GLOCK uniquely revolutionized the trigger with this safe, simple and fast two-stage trigger system that allows the operator to fully concentrate on shooting without having any additional safeties to disengage and reengage. GLOCK’s unique trigger is a fully automatic safety system consisting of three passive, independently operating, mechanical safeties. All three safeties disengage sequentially as the trigger is pulled and automatically re-engage when the trigger is released. These three automatic, independently operating, mechanical safeties are built into the trigger’s fire control system of the pistol. Additionally, this style trigger provides a consistent pull from the first through the last round.

Pull-Release Triggers

Next we have the hybrid pull-release trigger. This trigger is a very specialized hybrid trigger used exclusively for competition trap (or other clay bird) shooting. Some shooters develop bad habits like flinching or raising their heads off the gun as they pull the trigger in subconscious anticipation of the recoil. Breaking bad shooting habits is exceedingly difficult, time consuming and expensive. Some shooters use the pull-release trigger as a means to counter their flinching habit.

The pull-release trigger works like this: The competitor loads, closes and shoulders his gun. Prior to yelling “pull,” the shooter pulls the trigger and holds it in the full back position with his trigger finger. He then yells “pull,” and the clay bird is released. To fire the gun, he releases his finger from the trigger instead of pulling the trigger. This is obviously a very unsafe trigger for most everyone, save a very select few, and can only be used on a competition trap field. Should the shooter decide not to fire the gun once the trigger is in the full pulled-back position, he can only de-cock the trigger by opening the gun using his opposite hand. These highly specialized (and expensive) competition shotgun triggers don’t have safeties built into them. These guns are only loaded and cocked just prior to calling for the clay bird, and they’re never carried loaded or used for any other purpose than for competition.

How Pull Is Measured

At this point, a quick discussion of how the trigger pull is measured in pounds of pull is in order. The handheld scale used to measure pounds of trigger pull looks much like the portable scale used by fishermen to weigh their fish. The major difference is its precision. The trigger break weight scale is hooked onto a cocked trigger (of an unloaded gun), and the trigger is pulled using the scale until the trigger releases. The pound value measured by the scale at the trigger release is the trigger break weight required to fire the gun—it’s that simple. For example, a gun with a 3-pound trigger break weight has a much easier (lighter) trigger pull compared to a gun with a 6-pound trigger break weight; and so it goes that a 3-pound pull would likely be very suitable for competition or sniper use, compared to a harder 6-pound pull being more suitable and safer for hunting purposes or for military rifles intended for rough use.

Other Terms

Another term commonly misunderstood is trigger reset. Trigger reset refers to the full cycle mechanical operation time (swing) a particular trigger design requires from pull to reset for the next shot. In simple terms—it means the total time duration from the trigger pull to sear release until the trigger is reset and ready to fire the next shot. Therefore, the speed in which a trigger resets is dependent upon the trigger type and how fast the gun mechanism, as a whole, operates.

Rarely are a shooter’s reflexes faster than the trigger reset. Obviously, two-stage triggers have greater return distance (travel) than single-stage triggers, so the trigger swing time is greater which increases trigger reset time. Trigger manufacturers that advertise high-end, fast resetting replacement triggers are outright misleading shooters into paying for something that can’t be physically realized by 99% of shooters. Save your money.

The term trigger slap is somewhat misleading, but here’s a layman’s explanation. Trigger slap is not the result of a faulty trigger. If the trigger “slaps” your finger when the gun fires it’s because you lost trigger contact, and your finger is in the wrong place. Trigger slap can cause minor stinging pain but not any permanent injury to the trigger finger. Inexperienced shooters often experience trigger slap because their grip is inconsistent or loosely held. The remedy is easy. Grip and operate your firearm’s trigger properly, and trigger slap will not occur.

More experienced shooters tend to keep their finger on the trigger throughout the gun’s firing cycle. Upon firing, they move their finger slightly forward until the trigger resets, and they then begin the rearward pull. This process is very subtle and is executed seamlessly as the gun recoils. As the shooter “rides” his gun’s recoil back to its original on-target position, the shooter is ready to take the next shot without having to take the slack out of the trigger again. This is a normal trigger manipulation technique when (“double tapping”) firing two (or more) shots in very rapid succession at the same target.

Length of pull is also a term that seems to always confuse gun owners. Length of pull is the distance, measured in inches, from the trigger shoe/bar (point where your finger touches the trigger to pull it) rearward, to the stock buttplate/recoil pad (the rearward part of the gunstock you place against your shoulder). Most out-of-the-box long guns without adjustable stocks have a 13- to 14¾-inch length of pull.

Why is length of pull important? It’s really all about the shooter’s proper eye alignment with the gun sights and shooting comfort. A short length of pull will usually inhibit proper sight alignment as will an excessively long length of pull. If a particular firearm is used under different environmental conditions where the shooter may range between wearing a heavy winter hunting coat to a summer T-shirt, an adjustable stock should be considered. This allows the actual length of the gunstock (length of pull) to be adjusted to the shooter’s dress, providing consistent length of pull for eye relief and sight alignment.

This is where it gets confusing. A number of manufacturers tout adjustable triggers on their factory firearms, as do some of the replacement trigger manufacturers. In most of these cases the adjustment they are marketing involves the ability to adjust the first-stage pull pressure on a two-stage trigger. This is accomplished by tweaking a small screw that tensions the trigger spring. It doesn’t contribute to trigger system reliability because it adds one more moving part that can fail.

Some trigger manufacturers offer an adjustable trigger shoe that rides on a dovetail slot (or a similar sliding track) that is fixed by a small Allen screw. This allows the shooter to move the trigger slightly forward or rearward along a track to best fit individual hand geometry. This is not an adjustable trigger. It is an adjustable length of pull trigger. These can be found on many competition long guns (with pistol-grip-style stocks) and on competition handguns. It serves to adjust the trigger reach to better fit individual hand geometry. That said, adjusting the length of pull involves adjusting the length of the gunstock.

Trigger Geometry

Trigger shape presents an additional conundrum for many shooters. There are two trigger shapes: the curved (crescent) traditional shape and the flat (straight-blade) trigger. The flat blade trigger is often marketed as a newly invented accuracy upgrade for both pistols and long guns. That couldn’t be further from the truth. Flat blade triggers can be traced back to the earliest firearms used centuries ago.

The reason some shooters favor a flat trigger is because the trigger finger makes more uniform contact with a flat vertical trigger blade than a traditional curved (or crescent blade) trigger. This matters most for handguns when drawing from the holster. If it seems your trigger finger never lands on the exact same spot on the trigger, that’s because it likely doesn’t, especially if you tend to carry using different style holsters, e.g., ITW, scabbed, canted, shoulder, etc. Different style holsters present the pistol differently when drawing. This results in an inconsistent grip, and grip translates to trigger pull that can range from ideal to disparate. Notwithstanding, there are other variables that impact the trigger finger’s position as well.

One’s hand geometry (hand shape and size) is a huge factor when choosing a trigger replacement or new gun trigger shape. It always seems to be the proverbial “small gun verses large hands,” or the reverse, that exacerbates the grip by pushing the hand lower or higher on the grip. This variable results in either an extended trigger finger reach or a trigger finger tailback. Rarely does an out-of-the-box gun’s geometry ideally fit the shooter’s hand or length of pull dimensions. Therefore, a flat trigger helps ensure the trigger pull length is more uniform no matter where the trigger finger makes contact on the blade.

Correspondingly, the advantage to a curved trigger is that the trigger reach (defined as the distance from the back of the grip to the trigger face) is shorter in the middle of the trigger blade than at the top or the bottom. So your finger naturally finds the center of the trigger blade, and you don’t have to reach as far. A curved trigger is also a must if you’re shooting with a gloved hand; that’s why military and other tactical weapons all use curved triggers. The second reason is that a curved trigger readily accommodates a more diverse range of hand sizes/geometries with optimum pull comfort.

It all comes down to this. The above pros and cons, while true in a practical sense, don’t mean a thing in a gunfight. If you’re shooting holes in paper targets, the arguments for and against a particular trigger shape might matter but not in the real world. In the real world, it all comes down to personal preference and what works best for you. So before spending a lot of money to replace your trigger for a particular sexy shape, give it some real-world consideration and save the money for upgrades that really don’t make any notable difference.

Things to Remember

In closing, there are several points you should remember when it comes to triggers. First, keep it simple. The more adjustments that are incorporated into a trigger system, the more points of failure are added. Precision and its inherent level of complexity are fine when the firearm is dedicated to target shooting, but complexity is a reliability detractor in every other use scenario, especially defense.

Second, never attempt to “tune” a factory trigger yourself unless you are skilled at doing such things. Honing the sear to smooth the trigger break as a home gunsmith enthusiast can compromise a gun’s operating safety. Obviously, you want the gun to fire when you pull the trigger, not any other random time you happen to set it down hard or bump it against something.

Third, replacing your trigger is always an expensive decision no matter what type of replacement you choose to use. Ensure you know why you’re replacing the trigger. For example, replacing a 6-pound, single-stage trigger on an AR frame with a modular 3½-pound, two-stage target trigger may compromise your safety along with those around you, especially if you’re using your AR for something other than target shooting. Last, just because a replacement trigger costs a lot of money doesn’t necessarily make it a better trigger than one that costs half as much, or the one you’re currently using. Do your research and analysis before replacing your trigger. Your local gun shop salesmen are usually not an authoritative source of trigger information; neither are the blogs. Reading product user testimonies is always nice but understand most people have limited experience and little technical knowledge about what they’re blogging about. Remember, the average user’s feedback information is overwhelmingly subjective. Where does one go for accurate information? Shooting competitors’ and armorers’ forums usually provide a good source of information.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V24N10 (December 2020) |