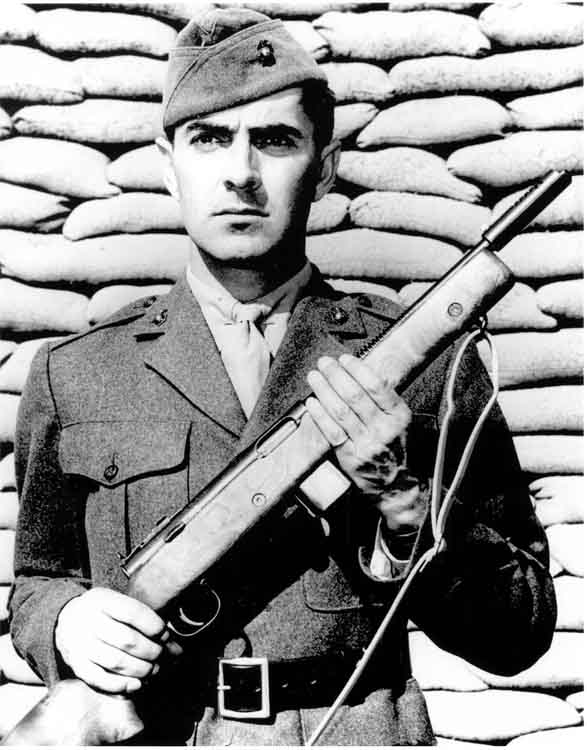

Mr. Eugene Reising 1884-1967

Eugene G. Reising was born on 26 November 1884, in Port Jervis, New York. He attended Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. During his career, Reising worked for several firearm manufacturing firms as a designer and while working under John Browning, made significant contributions to the design of the 1911 pistol. A designer of some note, Mr. Reising had more than 60 firearm related patents.

During 1938, the world watched as situations in Europe and the Far East deteriorated and it soon became apparent that war was on the horizon. Eugene Reising, anticipating a demand for military weapons, began designing his submachine gun in 1938. Reising’s approach to a submachine gun design was somewhat different than the standard open bolt configuration, common on submachine guns of the day. The open bolt design made the submachine gun a simple and easy to manufacture weapon. However, the flaw of the design was excessive weight, especially when considering their relatively low-power pistol cartridges. Eugene Reising’s idea was to use a delayed locking system like that used in semiautomatic pistol designs and would allow his submachine gun to be accurate in semiautomatic fire and weigh less than any existing submachine guns.

Reising negotiated a deal with Harrington and Richardson in 1939, where H&R would manufacture his submachine gun at their Worcester, Massachusetts facility and he was to receive a $2 royalty for each Reising gun sold. A patent for the Reising submachine gun design was filed June 28, 1940. A second patent for an improved design was filed February 7, 1941. Patent numbers 2,356,726 and 2,356,727 were granted on August 22, 1944.

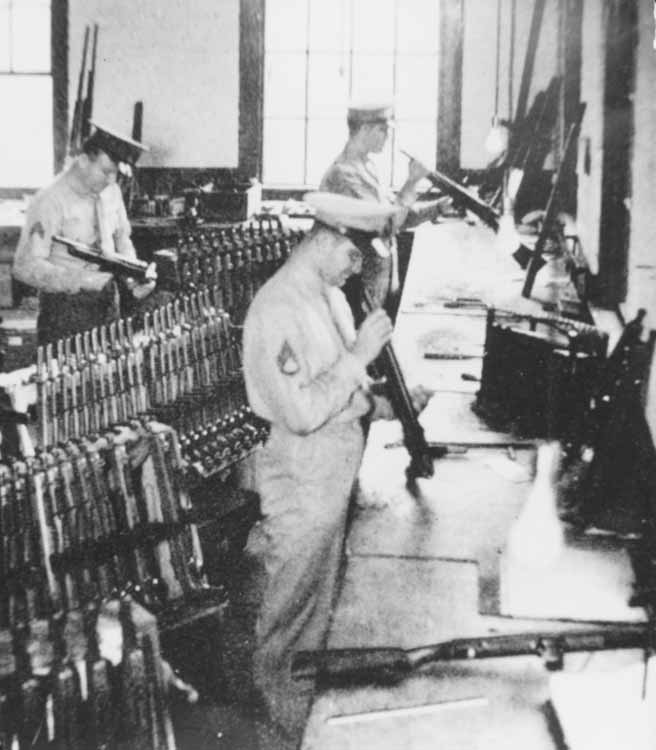

Harrington and Richardson

The Reising Submachine gun was manufactured by the Harrington and Richardson Arms Company from 1941 to 1943. The first order of 4,000 Reisings, received in March of 1941, was destined for Indochina. Other Lend-Lease orders included 6,000 Model 50s for the Soviet Union and 2,000 for England. During World War II, 114,216 Reisings were produced. By 1943, the Marine Corps had procured 66,500 Model 50 and Model 55 submachine guns in four separate contracts, over half of the total production. The remaining Reisings were purchased by police departments, domestic and foreign governments. Production of the Model 50 resumed at H&R in 1950, primarily for the domestic law enforcement market. Production ended in 1957.

Problems Arise

What made the Reising submachine gun unique was its weight of only 6.75 pounds for the Model 50. This was accomplished through the weapon’s closed bolt design. However, the Reising’s closed bolt feature was also one of the principle reasons for its failure to be consistently reliable in combat. To operate, the bolt tilted up into a recess in the receiver and momentarily locked until the cartridge was fired. Problems arose when dirt or any type of foreign debris got into the receiver recess preventing the bolt from locking up completely and the weapon would not fire. The required lubricants compounded the problem by attracting dirt. The Reising also had several other problems contributing to its poor reputation. The twenty-round magazine was the unreliable double stack, single feed design. Compounding the problem were the magazine’s thin, easily distorted feed lips. After numerous complaints of magazine failures a new magazine was designed and introduced. The new magazine was the more reliable single stack, single feed design, but this reduced the magazine capacity to only twelve rounds. The Reising also had a problem with interchangeable parts. When minor repairs were attempted in the field, it was often discovered that the replacements parts would not fit; it was just another fatal flaw the Reising possessed. The biggest mistake was adopting the weapon without sufficient testing; the rush to get weapons into the field was a contributing factor.

The U.S. Marines first fielded the Reising in combat operations against the Japanese during the battle for Guadalcanal. The abundance of sandy terrain on the tropical island jammed many of the Reisings rendering them useless. As long as the Reisings were kept clean they worked, but keeping them clean in a combat environment was nearly impossible. Another common problem reported by the Marines was that the commercial blued finish on their Reisings began to rust after only a few days exposure to the humidity on the island. After numerous reports of the Reising’s failure in combat, the weapons were pulled from front line service and relegated to rear echelon troops.

During a post war interview, Eugene Reising was questioned about the poor showing of his submachine gun. He stated that there was never a formal complaint received from the Navy Department on the performance of the Reising submachine gun in combat. He explained that Harrington and Richardson Arms, Inc. had in fact not received complaints, but five production excellence awards from the Navy Department. Mr. Reising seemed to be of the impression that much of the Reising gun’s negative image was generated from a single incident on Guadalcanal when Marine Colonel Merritt Edson ordered the guns to be thrown into the sea. He did acknowledge there was a problem with interchangeable parts on the Reising guns, and that this had caused problems in the field. He said that there was such an emphasis on production, there was no time to engineer the weapon to have completely interchangeable parts. He concluded by pointing out that Reising submachine guns were evaluated several times by the military before being approved for procurement.

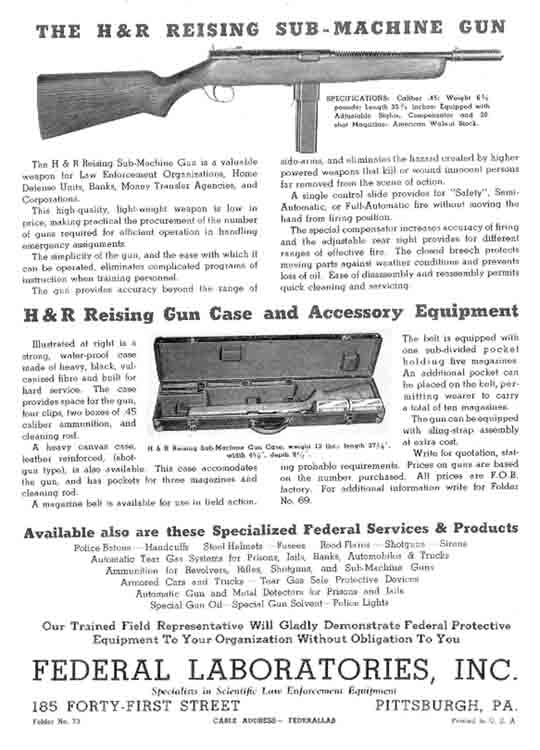

The Reising in Law Enforcement

Quite a few law enforcement agencies purchased the Reising and many prisons used them to arm their guards. The Reising was less expensive than the Thompson and considered to be more accurate when fired in the semiautomatic mode. When properly maintained, the Reising proved to be satisfactory for its law enforcement role. The primary distributor for the Reising both during and after World War II was Federal Laboratories of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The law enforcement demand for the Reising was such, that H&R resumed production of the weapon in 1950.

The “Commercial” and “Military” Reising Myth

The early manufactured Reising submachine guns are usually classified by collectors as the “police” or “commercial” model – these being the earlier blued guns with the 28-fin barrels. The second reference to the Reisings is the “military” version, the later production Parkerized 14-fin barrel guns. Although collectors and enthusiasts commonly use these references, both of the nomenclatures are incorrect. The H&R factory did not ever acknowledge in any documents separate commercial or military models. The only reference H&R used for the .45 caliber Reising guns was the Model 50, 55 and 60. The Marines procured both the early blued guns as well as the later manufactured Parkerized ones. The police purchased both variations as well.

Transitional Guns

During the manufacture of firearms, there are usually improvements and design changes introduced during the production run. This occurred during Reising production and many submachine guns were assembled with a mix of the new and old design parts. These guns are generally referred to by collectors as transitional guns.

Reising Dates of Production

1941 Serial Numbers: 101-8500

1942 Serial Numbers: 8501-73600

1943 Serial Numbers: 73601-114317

1950 Serial Numbers: K101 to K973

1951 Serial Numbers: L101 to L3589

1952: No production

1953 Serial Numbers: N111 to N327

1954-1956: No production

1957 Serial Numbers: S4700 to S5607

Marine Contracts:

NOm 33387 – 2 February 1942: 2,000 each Model 55 Reising submachine guns.

NOm 33660 – 26 February 1942: 11,500 Model 55, and 11,500 Model 50 Reising submachine guns.

NOm 36828 – 13 July 1942: 20,000 Model 55, and 5,000 Model 50 Reising submachine guns.

NOm 37893 – 13 October 1942: 30,000 Model 50 Reising submachine guns (plus a 3,000 overrun).

Receivers

The receivers on all of the .45 caliber Reising models were machined from 1.25 inch round steel stock. The early 1st design/late 2nd design receivers are easily identified by the direction of the logo stamped on the top portion of the receiver. The receivers on the earlier guns have the logo marked on the top so that it is read from the right side of the weapon. The receivers used on the later manufacture guns are marked to be read from the left side. In virtually all cases, except for transitional guns, the early receivers read from the right side will have the 28-fin barrels and other early features. Receiver’s read from the left side will have the 14-fin barrels and late features. The early receivers will have one spring-loaded end cap locking ball to secure the bumper plug and later receivers will have two locking balls. A slight discoloration of the finish may be evident near the center of Reising receivers. This was a result heat treating to harden the bolt locking lug. This is particularly noticeable on Parkerized guns. The early 1st design receivers were heat treated manually while the process on 2nd design receivers was automated.

Barrels

All .45 caliber models of the Reising were fitted with barrels made from nickel steel. The breech end had 7/8-18 threads to screw into the receiver. The cooling fins were turned on the barrel with a form cutter. The barrels were rifled by the broaching method with a 1 turn in 16 inches, right hand twist. During the third Marine contract, the number of radial barrel cooling fins was reduced from 28 to 14 in order to increase the structural strength, and to reduce labor hours.

Disassembly Screw

There is a single screw assembly is used to secure the barreled receiver to the stock. It consists of a threaded fastener with a curved washer attached. The washer is attached to the stock by two nails and the washer is secured to the shank of the screw to retain it when loosened. The configuration of this assembly on the early models is different than on later versions. On the early guns the screw is small, requiring a tool to turn it. When tightened, the screw head fits flush with the stock. On the later production, the screw is larger in diameter and thicker. The edge of the screw head is knurled and extends slightly below the stock. This type can be tightened or loosened easily by hand, or with the rim of a cartridge.

Bumper Plug (Receiver End Cap)

The Reising had four different designs of bumper plugs. “Bumper plug” was the nomenclature the H&R Company used for the threaded end cap that screws into the rear of the receiver. In the early designs, the recoil spring guide rod was manufactured as an integral part of the end cap and was a hollow steel pin. This style cap was used in many of the early model Reisings. There were a few problems encountered with this design as the steel guide pin would often break off the cap and bind the recoil spring causing the weapon to jam. The second design of end cap was similar to the first except that a solid steel pin replaced the hollow guide pin used in the earlier design. The pin was still an integral part of the cap. This style proved to be no more reliable than the original design.

The third design of end cap also had a solid integral spring guide pin, but the end of the pin was slightly tapered. This was done to try and eliminate the pin breakage problem of the earlier designs. This style cap was used in most of the early production Reisings fitted with the 28-fin barrel and some of the early production of the 14-fin barrel guns. Unfortunately, the problem of the guide pin breaking still existed. The breakage problem was eventually traced to the receiver threads for the bumper plug not being machined concentric to the receiver.

The fourth design cap was designed to alleviate all the problems of the original one-piece caps. The new cap was designed as two pieces, making the guide rod separate from the end cap. This solved the problem of the bending or breaking of the recoil spring guide rod. The new design spring guide rod was hollow rather than solid. This new design guide rod was used on all but the earliest second design Reising production. The end caps are completely interchangeable between models.

Magazine Housings

The magazine housing on a Reising serves two purposes. One is to hold the magazine in position, the other is to support and guide the action bar. Several different style magazine housings were used on the Reising during their production run. The magazine housing retaining pins also differed slightly between the early and later models.

Stepped Housing (First Design)

The first production Reisings were fitted with a magazine housing that was narrower in width at the rear. This was necessary to house the magazine release and at the same time keep the opening small enough to have a secure fit around the magazine. This housing was made from two separate pieces, the top plate and the housing body. The top plate was attached to the housing by welding.

Magazine Housing (Second Design)

This housing was stamped from a single piece of sheet metal, rectangular in shape, and there was no rear step on this design. A pin was inserted in the rear part of the housing acting as a spacer to keep the magazine in alignment. This eliminated the need for the “step” used in the earlier housing design. This is the most common type of housing and was used in both early and late production Reisings.

Magazine Housing (Third Design)

This magazine housing was also pressed from a single piece of sheet metal and it was designed to only permit the insertion of the twelve-round magazine. The housing was designed with an indented rib at the center that limited the inside dimension of the housing, preventing the use of twenty-round magazines. These housings were used in the late production Reisings.

Magazine Release Lever

One of the components that were changed several times during production was the magazine release lever. The first design was a simple spring steel lever with a hardened steel pin spot-welded to it. The lever was attached to the magazine well housing with a small screw. The rounded end of the lever had small lines depressed into it to make it more slip resistant. These style levers were used on the early blued guns. On later Reisings, this lever was slightly redesigned to have a smaller pin for holding the magazine in place and the lever itself was widened.

The magazine lever evolved into the next design that primarily appeared on transitional mid-production Reisings. These were often fitted along with the milled three-screw trigger guard. This type lever was manufactured in two pieces and was designed to release the magazine by pushing on the lever rather than pulling it. The release tab at the end of the lever was U shaped for added strength. On late production Reisings, the magazine release lever was redesigned to be more durable and easier to operate. These levers were also made in two pieces; the lever and the end piece. The end piece was made so it would pivot and use leverage to release the magazine.

Sights

The rear sight was fitted into a dovetail slot milled into the receiver. The sight on the Reising submachine guns was an aperture style and adjustable from 50 to 300 yards. This could be accomplished by lifting up the sight and sliding a notched elevator forward or rearward. The later manufacture Reisings had a screw installed to secure the sight onto the receiver.

The front sights were an unprotected blade design. On early guns, the front sight was fixed, staked into place and non-adjustable. The very last production 28-fin barrels had front sights that were adjustable for windage by loosening a small setscrew, and drifting the sight right or left. The 14-fin barrels had the same feature.

Part II will cover Reising Accessories.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V14N7 (April 2011) |