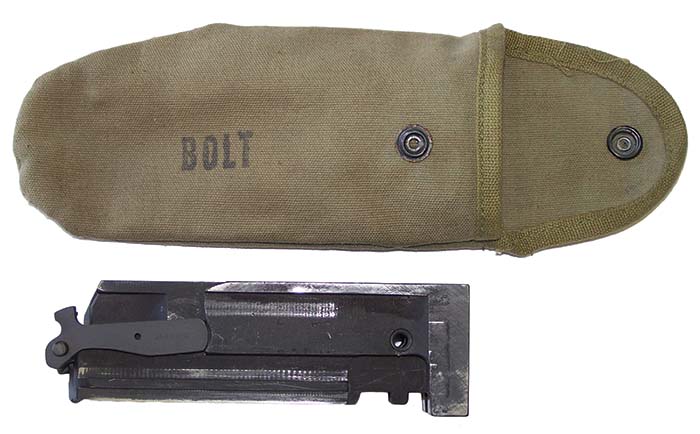

M9 spare barrel cover and barrel assembled to barrel extension. The cover was designed to hold the entire assembly so that the barrel and barrel extension could be changed as a unit. (Charles Brown)

By Charles Brown

Canvas or fabric items created by or for various branches of the Army Services are an interesting study in themselves. While some of the accessories for the M1919A4 had other applications, the spare barrel cover and bolt case were weapon specific.

The variety is staggering as was the quantity in which they were produced during WWII. Both the spare barrel cover first produced in 1936 and bolt case in 1934 are quite common even today.

The M9 spare barrel cover is one of the items mentioned repeatedly in the 1941 Standard Nomenclature List for the M1919s. It was authorized as an accessory under the Equipment section for the M2 and M2A1, M3 tanks, M1, M2 and M3 scout cars, pack transport and ground and

train defense units.

Way back in February 1923, the Ordnance Committee took up Item 2684 concerning covers for machine guns and spare barrels. The Committee recommended that the Chief of Cavalry’s request for the expenditure of $198 for the fabrication of “34 machine gun covers and 24 spare barrel covers (experimental) under the supervision of Lt. Col. Albert E. Phillips, Cavalry, at Jeffersonville, Indiana” be approved. These covers were to be used in the testing of the Phillips standard pack saddles being developed at the Jeffersonville Quartermaster Depot. The Phillips pack saddle was adopted in 1924 after testing by Cavalry, Infantry and Mountain Artillery units.

So far the author has not been able to locate the drawings used to produce “spare barrel covers” mentioned in the Ordnance Committee Minutes.

It strains belief that the Chief of Cavalry, usually a Major General, had to get the blessing of the Ordnance Committee to spend $198 but then again, it was the interwar period with the Congress and the public longing for a return to pre-war isolationism, their near pathological fear of militarism and the desire for a defense establishment run on the cheap.

Col. Phillips was part of the Calvary Branch that built upon one of the lessons of WWI; namely that saber charges against a machine gun armed enemy weren’t going to cut it, no pun intended, but there were not quite ready to abandon the horse due to tradition and the perceived unreliability of motorized transport.

With horse mounted charges out of the picture this left the cavalry with the jobs of screening, scouting and becoming mounted infantry equipped with pack transported automatic weapons. The M3 Machine Gun Hanger for the M1919 series of weapons and the M8 Machine Gun Ammunition Hanger were also developed as attachments for the Phillips standard pack saddle.

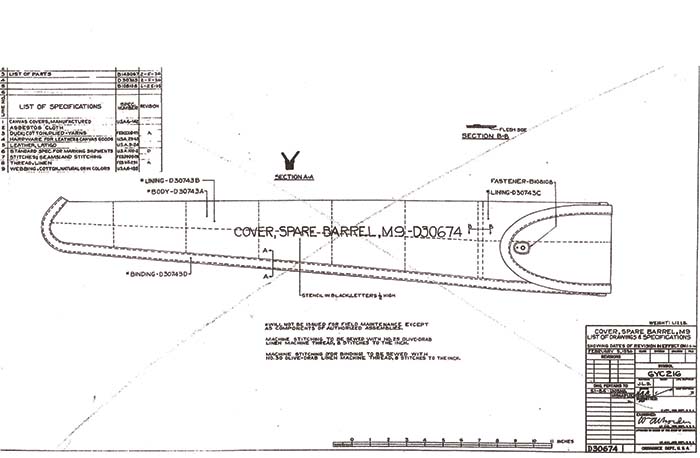

The original design drawing of the M9 barrel cover dates from February 1936, which is near the time line of two events: the transfer of engineering and manufacturing responsibilities for the .30 caliber Browning ground guns from Springfield Armory to the Rock Island Arsenal caused by Springfield’s preoccupation with getting the M1 rifle into production and the growing feeling in the Army, especially the Cavalry, that a standard air cooled machine gun and light weight tripod, something missing from their TO&E, would change combat power for the better.

The M9 was designed to carry the barrel and the barrel extension assembled as a unit. This method of carry would speed up barrel changing and the required head spacing whenever barrel, barrel extension, bolt or lock frame was changed.

The M9’s original design reminds the author of the off told story of the military’s purchase of a $2,000 toilet seat. The lower end of the cover was lined with asbestos cloth and the upper part including the closure flap with latigo leather. Apparently the theory was that the hot barrel would not char the asbestos cloth and the leather prevented wear from the edges of the barrel extension. The linings added material expense, manufacturing cost and needless complexity to what was essentially a simple canvas bag with a fastener. The 1941 cost of a lined M9 spare barrel cover was $2.90 with the leather and asbestos linings accounting for $1.10.

After the U.S. entered WWII great emphasis was placed on material conservation and the simplification of manufacturing, which increased production and lowered cost while minimally affecting the utility of the item.

One pre-war change to the barrel cover was lightening the weight of the binding material; this may have been done because the lighter weight binding was a commercially available standard.

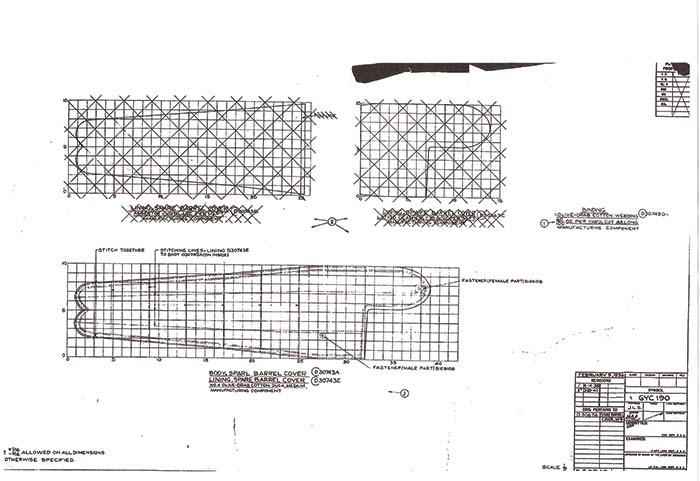

In March of 1942 the asbestos and leather linings were dropped in favor of a double thickness of No. 4 Olive Drab Cotton Duck, which was the original specification. In 1942, asbestos was not considered to be a significant health hazard and it was used in everything from brake linings to pipe lagging.

Regardless of the fact that these design changes occurred over 70 years ago, the lined barrel covers are surprisingly common. As with many WWII canvas products the dye shade of the material varies along with the binding.

No attempt was made match the binding color to the body resulting in some variation in appearance. The color of the body can vary considerably as the Army changed colors at least twice, but apparently used whatever material color at hand. The closure flap is secured with a “lift the dot” fastener.

The double thickness of cotton duck was stitched together in several places to prevent separation of the plies and add a little rigidity.

Typically, covers are stenciled or stamped “COVER, SPARE BARREL, M9-D30674” in ½ inch letters and various fonts were used. Most of those observed by the author are neither maker nor MRT (mildew resistant treatment) marked or have any sort of inspection markings.

The CASE, Spare Bolt, M2 dates from June 1, 1934, and the original drawing makes no mention of any previous versions that may have been left over from the WWI era Class and Division drawings for the Model of 1917 Browning or other weapons although the bolt assembly is common to the Model of 1917/M1917A1 and the various M1919 models. The case was fabricated from OD cotton duck with bound exposed edges and stitched together with No. 25 linen thread, 8 stitches to the inch. The closure flap was secured with a simple snap fastener. The face of the cover body was stamped or stenciled with ½ inch letters “BOLT”. The 1941 price of the M2 case was $.80.

The original drawing for the M2 has a “List of Contents” block that lists “Bolt, Feed, Assembly” with no drawing number or piece mark as the contents. Apparently there may be a nomenclature difference between the bolt assembly, which is the bolt and recoil plate, and bolt feed assembly, which the author presumes to be a bolt assembly with all the operational parts, cocking lever and pin, sear and sear spring, firing pin and spring, driving spring and rod and extractor assembly installed.

The M2 case was a convenient way to carry this field replacement component in useable condition in the field especially because the extractor assembly is readily dislodged and could easily be lost in a combat situation. Later versions of the drawing show just “Bolt Assembly” and list the drawing number B147299, which is just the bolt with the recoil plate installed. In the author’s view, attempting to assemble a complete bolt to return a malfunctioning weapon to service in combat conditions seems a little farfetched.

The M2 case appears in various dye-shade combinations like most other WWII era canvas goods and as with other fabric field items received MRT preservation after about mid 1944. Those cases with MRT mildew-proofing often have the treatment contractor’s name.

Although with a little care the case and bolt could be carried in the top of the M9 spare barrel cover by the machine gun section gunner along with the M2 tripod mount, the author does not know with much if any certainly if that was the prescribed method of transport.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V19N4 (May 2015) |