New Caledonia, South Pacific, 24 September 1945. An Army bazooka team demonstrates loading the improved M6A1 rocket in the M1A1 launcher, easily identified by the absence of a SAFE/FIRE box on the top. Following safety guidelines in field and technical manuals, the “rocketeers” are wearing gas masks for eye protection, steel helmets, and gloves on the gunner. Credit: U.S. National Archives

By Robert Bruce

“Battlefield reports dictated a number of design changes, starting with deflectors to protect the gunner against backblast of slow-burning rockets in cold weather. This was followed by wrapping the rear section of the barrel with piano wire to reinforce it against detonation of rocket motors within the launcher, substituting a generator for batteries in the firing mechanism, eliminating the forward hand grip, and, in the fall of 1943, the most radical change of all, the take-apart launcher M9. Each design change posed its own problems, but, as the bazooka enjoyed such a high priority, nothing was allowed to stand in its way for very long. In fact, production schedules were met more consistently on the bazooka than on any other item of small arms manufacture.” [Procurement and Supply, see Ref. 2]

In the first installment of this two-parter, we closely examined the genesis of the “Bazooka,” a revolutionary addition to the infantryman’s arsenal. Now, let’s move ahead with a look at how combat experience exposed some flaws in the first production model launchers and rockets, forcing both life-saving and death-dealing modifications at a breakneck pace.

New and Improved

A brief note of characteristics and improvements to the M1 launchers and M6 rockets:

M1 (fires M6 Rockets), fielded in June 1942: Closely resembling the T1 prototype, this first production model is a 54 inch long thin steel tube characterized by two handgrips and a rectangular SAFE/FIRE “control box” on top. To accommodate right- or left-handed gunners, it has ladder type front sights on both sides of the barrel and a notched bar rear sight on an arm that swings to either side. Electrical ignition of the rocket motor is accomplished by a firing circuit powered by a dry battery housed in a wooden stock. Electrical contacts on the M6 rocket are an unpainted conducting band around the warhead and a taped down wire running along its length to the fins.

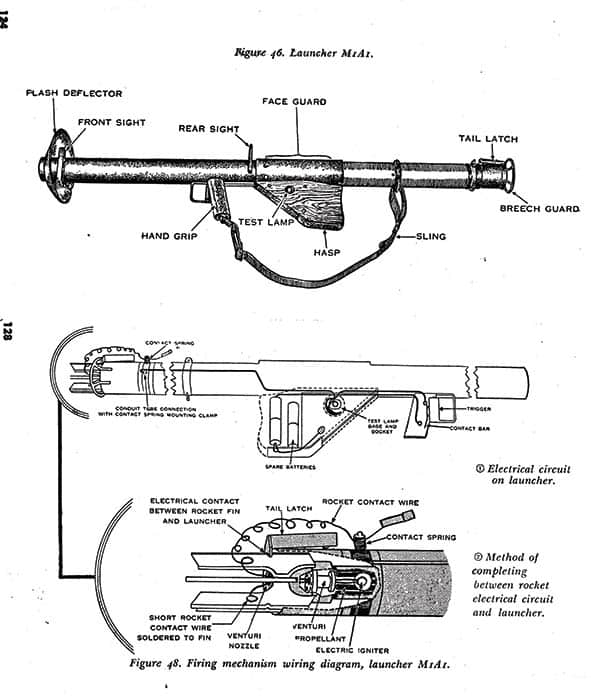

M1A1 (fires M6A1 and A3 Rockets), fielded in July 1943: Simplified version of the M1, modified to launch the new M6A1 rocket with improved propellant, strengthened motor tubing and internal electrical wires that are less prone to damage and resultant malfunction. Retains battery ignition but eliminates control box in favor of twin wire contacts at the rear. Single handgrip/trigger as well as fixed front and rear sights for right-handed gunners only. Adds flash deflector screen on the muzzle and steel wire wrapping to reinforce the rear of the launch tube against rocket motor detonation. Mount points for a carrying sling.

M9 and M9A1 (fires M6A1 and A3 Rockets), fielded October 1943: Much-improved version, readily identified by its two-piece launch tube with quick coupling collar. Integral muzzle flash deflector and a single handgrip housing a squeeze-operated magneto electrical generator. Significantly better accuracy due to the T90 optical reflex sight. Wood stock replaced with a sheet metal ribbon type with two shoulder rest positions that allow more comfortable firing in all positions.

M6A3 Rocket: Essentially the same internally as the M6A1, the new A3 features a rounded nose to improve warhead detonation when striking targets at more extreme angles and drum-style fins for greater accuracy in flight. Interestingly, the “new and improved” nose shape and fin configuration were taken from combat-proven M9 rifle grenades that had long been used side by side with bazookas. Armor penetration increased some 30% (from 3 to 4 inches) by changing the steel cone in the shaped charge to copper.

Bazookas on Beachhead and Battlefront

These improvements were driven by battlefield experience, received with utmost seriousness and implemented with astonishing speed.

First combat use of the bazooka came in the North African campaign that began in November 1942. GIs, who first saw the new contraptions while en route aboard troop ships, were severely handicapped by the absence of instruction materials and no opportunity for live fire training prior to the actual assault landings.

Three months later (presuming that this interval allowed the training deficit to be overcome) it was unfortunate, but not inexplicable, that bazookas weren’t notable in stopping German Field Marshall Erwin Rommel’s armored forces in the disastrous rout of US II Corps at Kasserine Pass.

Likely contributing to this was poor reliability from an unfortunate combination of inherent flaws with hastily manufactured launchers and rockets coupled with mishandling by the rookie “rocketeer” teams. And when the rockets did launch and hit, the frontal and side armor on Rommel’s tough Tiger and Mark IV tanks was too thick to be penetrated.

It’s understandable that the radical new weapon’s performance as an effective anti-armor weapon was a disappointment to its Ordnance proponents, not to mention the unlucky GIs faced with latest-generation German tanks. This set in motion a determined and widespread effort to fix the chain of problems from factory to fighter that paid off in the next big Allied push.

“The work of the bazooka in the landings [Gila, Sicily, July 1943] and throughout the campaign was watched with great interest. One Ordnance observer claimed that bazookas accounted for Pzkw IV tanks on four occasions; another claimed a Pzkw VI Tiger, though admittedly the Tiger was knocked out by a lucky hit through the driver’s vision slot. On the other hand, many officers preferred the rifle grenade to the bazooka as a close-range antitank weapon. An interesting discovery made in Sicily was that the bazooka was effective as a morale weapon against enemy soldiers in strongpoints and machine gun nests.“ [On Beachhead and Battlefront, see Ref. 2]

While the bazooka got better and better as GIs pushed German and Italian enemy forces back into Europe, it was also showing both potential and problems in the Pacific Theater.

For Army and Marine infantrymen facing off relatively few and lightly armored Japanese tanks, the bazooka proved a particularly deadly weapon against far more numerous enemy bunkers and caves…when it worked. But failures to fire, as noted in North Africa, were even more common in the torrential tropical rains and steaming jungles of island-hopping warfare.

Corroded electrical contacts, battery problems and moisture-damaged rocket propellant were most often cited in battlefield reports, rapidly leading to improvements to the M1A1 and then the completely redesigned M9, best of the series. Most notable for replacing batteries with magneto ignition and separating the tube into two parts with a quick coupler, the M9 and M9A1 launchers with M6A3 rockets were highly effective in crippling the heavier model tanks and blasting bunkers and caves.

Damn good, but not nearly good enough.

The Bazooka’s German Babies

“On the performance of the bazooka, opinions varied. The general feeling was that it was good but ought to be better. One assistant division commander complained that ‘we’re still using the same model we started with’ while the Germans have ‘taken our bazooka idea and improved upon it.’ The Germans had produced more deadly antitank weapons of this type in the Panzerschreck and Panzerfaust, both of which, however, were extremely dangerous to the user. The Panzerfaust, a recoilless weapon firing a hollow-charge grenade, would pierce seven or eight inches of armor plate. Some U.S. combat officers collected all they could get their hands on for their troops; one tank officer considered the Panzerfaust ‘the most concentrated mass of destruction in the war.‘” [On Beachhead and Battlefront, see Ref. 2]

As previously noted in Part 1, our British and Russian allies had urgently requested bazookas and both got some from the earliest production run in 1942. The Brits thought about it and then inexplicably clung to the woefully inferior PIAT.

The Soviets, while favoring marginally effective anti-tank rifles of native design, apparently tried bazookas in battle and therein lies another fascinating tale, necessarily abbreviated here.

American M1 launchers and M6 rockets in use by the Red Army were soon captured by the Germans, quickly evaluated and greatly improved, resulting in the Raketenpanzerbusche 54, better known as the Panzerschreck, which is literally translated as “tank terror.”

This was a bigger and better bazooka; a shoulder-fired launcher for a much larger and more powerful 88mm (3.5 inch) diameter rocket. Capable of defeating 100mm/4 inches of armor, it was first encountered by U.S. forces in 1943.

The ingenious Panzerfaust (tank fist) followed, changing the bazooka concept of a rocket, to a cheaply manufactured single shot recoilless rifle, firing a series of increasingly powerful shaped charge warhead tipped grenades from a skinny, throwaway launch tube. (See back issues of SAR online to understand the difference between rockets and recoilless launchers).

Bazooka Epilogue

While the American GI’s spunky little 2.36-inch bazooka was effective in many situations, its armor penetration was inadequate from the beginning and only marginally improved during WWII. The fact that examination of the much more powerful German 3.5-inch Panzerschreck didn’t result in a crash program that was successful in fielding beefed-up bazookas any time in the next two years of the war borders on criminal negligence.

Not to say that Ordnance didn’t try.

Bringing necessarily pragmatic “capture and copy” full circle, the enemy’s Panzerschreck birthed the U.S. 3.5-inch M20 “Super Bazooka,” beginning development in October 1944 but not completed before war’s end with the surrender of Japan eleven months later.

Worse, few M20s were available to luckless GIs in South Korea in June 1950, who were facing heavily armored Russian T34 tanks supplied to

the invaders.

Although the Panzerfaust didn’t seem to inspire U.S. ordnance personnel to pursue development, it certainly found favor with the Soviets, who refined and fielded it as the RPG-2 recoilless launcher, first encountered by American troops in Vietnam, and going on in various forms as the RPG-7 recoilless rifle using a rocket assisted grenade. The famous “RPG” has become almost as famous and recognizable worldwide as the AK-47 family.

Anti-Tank Rocket Launchers M1A1 and M9

Characteristics: “The 2.36-inch AT Rocket Launcher M1A1 is an electrically operated weapon of the open tube type. It is fired from the shoulder in the standing, kneeling, sitting, or prone positions. It is used to launch high-explosive rockets against tanks, armored vehicles, pill boxes, and emplacements. The rockets weigh approximately 3 ½ pounds and are capable of penetrating heavy armor at angles of impact up to 30 degrees. The weapon can be aimed up to distances of 300 yards. Greater ranges may be obtained by estimating the angle of elevation. The maximum range is 700 yards.” [FM23-30 and TM 9-294, see Ref. 3 and 4]

Length: M1A1.…54.5 inches; M9.…61 inches, disassembled 31.5 inches

Weight: M1A1.…13.26 pounds; M9.…15 pounds

Internal diameter: 2.36 inches (2.37 in. actual)

Ignition: M1A1.…Electric power supplied by dry cell batteries; M9.…Electric power supplied by trigger actuated magneto

Range: Point targets 50 to 300 yards; Area targets 300 to 650 yards

Elevation for maximum range: 40 degrees

Rate of fire: Approximately 10 rounds per minute

Sights: M1A1.…fixed aperture rear and ladder front (100, 200, 300 yards); M9. …Optical reflex sight T90

Ammunition: High Explosive Anti Tank Rockets M6A1 and A3, Practice Rockets M7A1 and A3, Smoke Rocket M10.

Accessories: Rocket carrying Bag M6, sling

Notes: M1 model fielded 1942, M1A1 fielded 1943, M9 fielded 1943. Approximately 490,000 of all models were manufactured by end of WWII. Primary contractor General Electric Corp for M1 and M1A1, with Cheney Bigelow Wire Works making the M9s.

Anti-Tank Rocket M6A1

Length: 21.6 inches

Weight: 3.4 pounds

Muzzle velocity: 265 feet per second

Penetration: 3 inches of homogenous steel armor to 30 degrees off perpendicular. 1 inch entry hole.

Primary References:

1. The author acknowledges with great appreciation the cooperation and assistance given by the director and staff of the US Army Ordnance Museum, recently relocated to Fort Lee, Virginia. Most notably some of the rare photos accompanying this feature as well as the September-October 1944 issue of ARMY ORDNANCE magazine with by-then Colonel L.A. Skinner’s article “Birth of the Bazooka: The Genesis of a Powerful Portable Antitank Weapon.“

2. Three volumes from the United States Army in World War II series, The Technical Services, Office of the Chief of Military History, US Government

Printing Office:

Ordnance Department: Planning munitions for War

Ordnance Department: Procurement and Supply

Ordnance Department: On Beachhead and Battlefront

(Many large municipal and university libraries in the U.S. are likely to have these and others in the United States Army in World War II series in their Reference sections. It is well worth the time and effort to find and examine them.)

3. War Department Basic Field Manual FM 23-30, HAND AND RIFLE GRENADES, ROCKET, AT, HE, 2.36-INCH, 1944

4. Ordnance Department Technical Manual TM 9-294, 2.36-inch AT ROCKET LAUNCHER M1A1, 1944

5. War Department Training Film T.F. 18 1166 “The Antitank Rocket M6”

(see YouTube video http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IRPsxgOozqk or search “Bazooka Rocket Launcher”)

6. U.S. Infantry Weapons of World War II, by Bruce N. Canfield, Mowbray Pub. 1994-96

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V19N10 (December 2015) |