By Gabriel Coutinho de Gusmão –

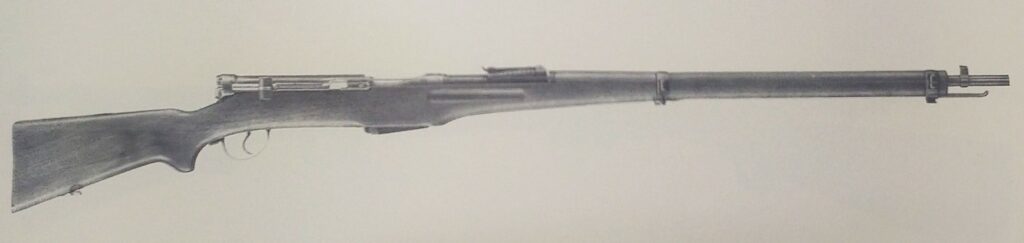

The first documented attempt at making a self-loading rifle comes from Austria-Hungary when Czech designer Karel Krnka attempted to convert one of his breech loading firearm designs into a self-cocking and ejecting firearm by the means of a primer-actuated system, in which the primer of the cartridge would return the firing pin back to its cocked position and then extract the spent cartridge. Later, in 1884 and 1885 respectively, both Maxim and Mannlicher made attempts at self-loading rifles of their own. Mannlicher made the first original design of what he called “Handmitrailleuse,” which is called a semi-automatic rifle today.

The last decade of the 19th century saw various inventors tinker with automatic repeating systems; Ferdinand von Mannlicher in Austria, Paul Mauser in Germany, Julius Rasmussen & Vilhelm Oluf Madsen in Denmark, Paul Darche and the Clair brothers in France.

Military theory of the time valued accuracy over any other attribute, therefore the trials of the Darche in France and the Griffiths & Woodgate in the UK were negative as they were not as accurate as the service rifles of the day, the Lebel and Lee-Metford respectively. Denmark tested the Madsen-Rasmussen self-loading rifle, finding similar problems as France and Britain had, as well as many problems with reliability and weight. Though they did see potential on the rifle as a supplement to their newly built coastal fortresses along the Copenhagen port, since they had cleaner environments and didn’t have to be carried on the march by troops. As such, 110 rifles of the 1896 pattern were bought by the navy and artillery departments, making the M1896 Rekylgevær the first self-loading rifle to be used in a military scenario.

Cost cutting is the way to adoption

While some inventors were busy with creating automatic mechanisms from the ground up, others took a different approach. If it was possible to convert the standard, already manufactured, bolt action magazine rifles of any country, it would be more attractive for adoption as new machinery and especially new rifles wouldn’t have to be manufactured.

However, modifying certain types of bolt actions was a complex, difficult task, and the resulting rifle was often not good enough by the military standards of the time. The biggest hurdle being the four-step movement of the bolt, with its vertical and linear movements. Systems had to either perform those four actions automatically, usually with a gas system plus a camming surface to guide the bolt, or they could be modified to run with only linear movement, akin to straight-pull rifles. These could be of any automatic system, including gas operated, recoil operated, primer-actuated and even chain-operated.

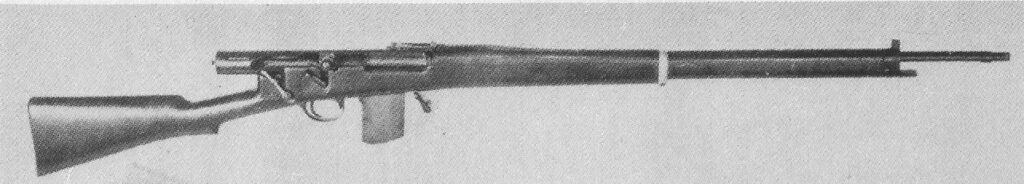

The first attempt, Italy

Amerigo Cei-Rigotti, at the time lieutenant of the Bersaglieri, presented his rifle on the 10th of October 1886 to the colonel of the general staff Gandolfi, head of the 19th Army Corps and to Deputee Palizzolo. It consisted of a modified Vetterli rifle, built to fire in semi-automatic using a gas-piston attached to the right side of the rifle. Cei-Rigotti also regarded that it was of such simple construction that it could be fitted to a Gras or even a Mauser rifle. The response of the attendees was very positive as they found it to be extremely cheap to modify said rifles, only costing one lira each, and it functioned very well in testing.

In 1895, he presented a more refined version of his rifle to the Prince of Naples in Florence and to the Minister of War in Parma. Both were very impressed and went ahead with ordering 2000 rifles for the Royal Italian Navy, to be used against enemy torpedo boats, just like the Danish Artillery Corps. Although, for reasons still to be uncovered, the adoption did not go through and the 2000 rifle order was never completed. Still, Cei-Rigotti persevered.

At the same time however, Count Gaspare Cesare Freddi also had been modifying the Vetterli rifle, except his system would only extract the spent casing automatically, the soldier would have to rechamber it manually. Freddi, nevertheless, persevered as he would provide another rifle for testing in 1900 which was properly self-loading, using a long recoil system. He presented it as being able to chamber any cartridge and being able to adapt it to fit in any magazine-fed rifle of the time.

Cei-Rigotti, now a captain, submitted a new rendition of his rifle again to the Italian officials on the 13th of June 1900, this time around they weren’t so impressed as the gun quickly overheated while being fired at around 900 rounds per minute. In the same year, Cei-Rigotti was in talks with the British small arms committee over having one of their service rifles, at the time the Magazine Lee-Enfield, sent to the Glisenti small arms company to convert it to the Cei-Rigotti system. It is unclear if this conversion was ever done. However, he proceeded to present one of his standard rifles to be tested anyhow. The British found it to be highly inaccurate while being fired in full automatic and they had problems with the reliability of the firearm, as they were provided with faulty ammunition.

Other countries, like Russia and Austria-Hungary, also tested his rifle. Recently an M95 Mannlicher converted with Cei-Rigotti’s system was uncovered in Russia, it is unknown how it got there but it clearly shows the interest of the Austro-Hungarians in this new system. There have been reports of a Mosin-Nagant modification as well, but no pictures have surfaced. It was even tested in the Americas, where there have been reports of the Cei-Rigotti in Argentina and Brazil.

As much attention as Cei-Rigotti got, he had a problem in his own home country. The Genovesi-Revelli rifle, a short-recoil conversion of the M91 Carcano, had recently been offered to the Italian government for a million lira. It was put to the test in the Terni state arsenal where it failed miserably. However, the Italian war minister did not reject the rifle outright. He instructed the Terni factory to fix the problems with the rifle, which they did after two years. The redesign was so different from the original Genovesi-Revelli system that the million lira price, paid for the original patent, was deemed worthless.

From Russia with Self-Loaders?

The Berdan was a breech-loading, 10mm rifle that Russia adopted in 1868. It proved to be remarkably advanced up until the advent of smokeless powder and automatic firearms were introduced in the 1880s. However, some entrepreneuring officers of the expansive empire took notice of the developments going on outside of their borders and worked on advancing this Russian rifle up to the modern age. One of these was a woodsman by the name of Rudnitsky, who presented a modified Berdan Rifle, now utilizing a short recoil system that had a tube magazine under the barrel. He began to work on this project in 1883. By 1887, he was ready to present it to the Russian artillery committee, although they were interested, the rifle did not perform well when tested.

After a couple of years and some other failed attempts at standalone self-loading rifles, a private and blacksmith by the name of Yakob Roschepei presented in 1905 a Mosin-Nagant modified to be delayed blowback. It worked well enough that he got employed at the Sestroryetsk Arms Plant where he continued to develop his concept until the Russian Civil War.

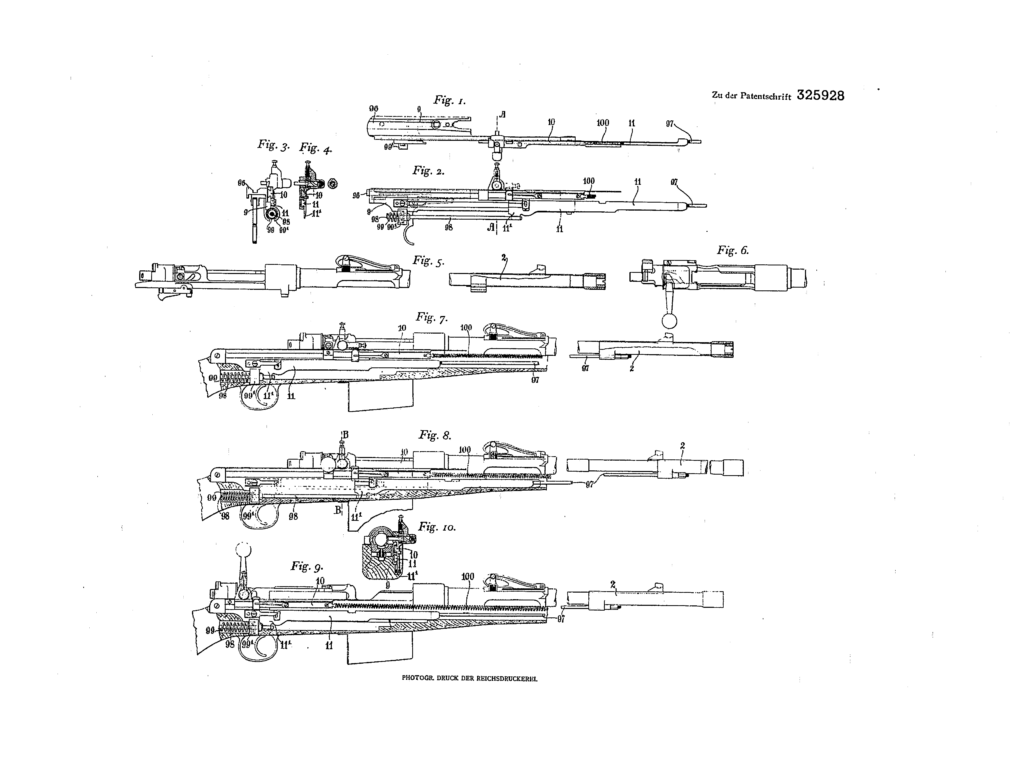

Vladimir Fedorov also presented one of his plans for converting the Mosin with an unknown operating mechanism in 1907, however, it did not function well. He would go on to improve his design and some of his rifles, now converted to fire from fully automatic, would serve in WWI and later, his model of 1919 would be used in the Winter War.

Another well-known Russian designer, Fedor Tokarev, would also start his lengthy firearm career by tinkering with the standard Russian service rifle. In 1909, he presented his first model for testing, which was outright rejected. His 1912 model fared better as 10 units were ordered for formal testing, though, they did not manage to get past the three sets of rigorous trials that the Russian commission had stipulated.

His final design in 1913 saw the best reception of them all, the commission indicated that his rifle deserved serious attention as it worked better than all other rifles submitted. However, in 1914, the war had been declared and further work would not be continued as Tokarev would be sent to the frontlines.

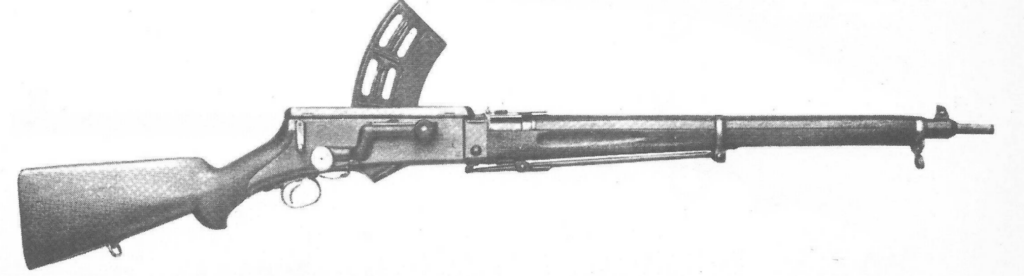

Also present in those same tests was Karl August Bräunings’ rifles, an engineer working for Fabrique Nationale in Belgium. They were both converted using the same action as his standalone automatic rifle from 1906, one of them having Braunings’ rotary magazine design and the other the standard of the Russian rifle.

The results were favorable enough that 10 rifles were ordered to be converted in 1913. Although with WWI beginning one year after, there was not enough time to properly test and adopt these rifles.

Another Inventor would be Pyotr Frolov, master of arms of the Tula State Factory, who in 1912 converted two Mosins to fire the Nagant M1895 cartridge in semi-automatic. Frolov also tried unsuccessfully to adapt his self-loading system to work with the Mosin-Nagant’s original cartridge. No reports have surfaced about any testing carried with this conversion system, so it is unknown why it wasn’t developed any further.

In 1916, having captured some Mannlicher rifles from Austria-Hungary, one Russian captain by the name of Yasnikov, added a gas-piston to one of those rifles and offered it for testing. The Russians found that with the added weight of the gas piston, the rifle became awkward and heavy and the rifle, now fully automatic, was seen as another negative.

The British Empire looks for a suitable self-loading rifle

The Small Arms Committee was formed in 1900 as a way for Britain to experiment and determine their own standing in the modern military world of the time. That included testing the growing numbers of semi-automatic systems developed across Europe. However, Britain had already tested a design dated to 1892 by Captain Herbert Woodgate and financed by William Griffiths. Tests of the Griffiths-Woodgate rifle would be favorable, though it was described as being too complex and too fragile in its current state. Griffiths’s financial support quickly dropped after realizing the rifle would go nowhere. Woodgate, the inventor, would later patent a conversion system for any magazine repeating rifle in 1895, however with no financial support, the project seems to have gone nowhere.

One of the other rifles tested by the SAC was the “De Faletans” rifles, named after its inventor’s title the Marquis de Faletans. The two rifles would be presented for testing in 1902, with the Marquis remarking that his proposed system of a semi-automatic system could be readily adapted onto the standard British service rifle, the MLE.

Franz Kretz and Edmund Tatarek, colleagues working for FÉG, both presented rifles for testing in March of 1914. Both rifles were gas operated conversions, utilizing a gas-trap system similar to the later General Liu rifle. Kretz’s submission utilized a complex chain mechanism to cycle the bolt, which when examined was found to be bulky, weak, excessively heavy, badly balanced, liable to break down, difficult to strip, and even more difficult to re-assemble. Tatarek’s rifle was of simpler construction, being compared to a combination of the Farquhar-Hill and Bang systems, however it was seen as never being able to be practical for field service.

During the Great War, Joseph Huot provided a machine gun that he built from a Ross Mk.III. It fared very well in tests and was sent abroad to the U.K. for trials against the Lewis gun, the Farquhar-Hill light machine gun, and the Hotchkiss Portative where it was formally rejected by the British Army.

Austria-Hungary stumbles into the scene

Austria’s standard service arm was the M1895 Mannlicher rifle, a straight pull bolt-action invented by Ferdinand von Mannlicher. As soon as 1900, patents would be taken out by one Franz Tobisch for a recoil-operated, gas delayed machine gun which utilized the bolt of the Mannlicher rifle as a savings cost method. It would also be applicable to Mauser-type bolt-actions. Although, until the later Franz Kretz conversion, as far as the author is aware, none of these conversions were ever produced for testing.

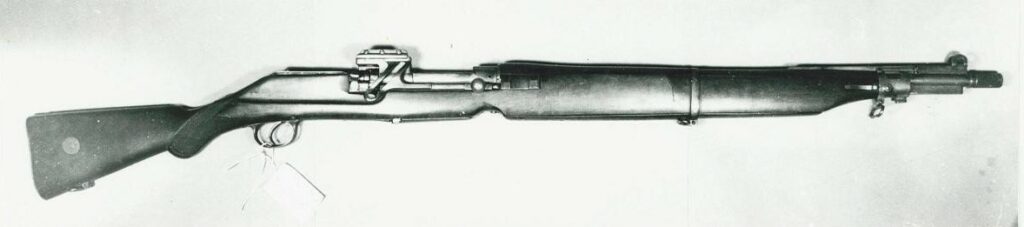

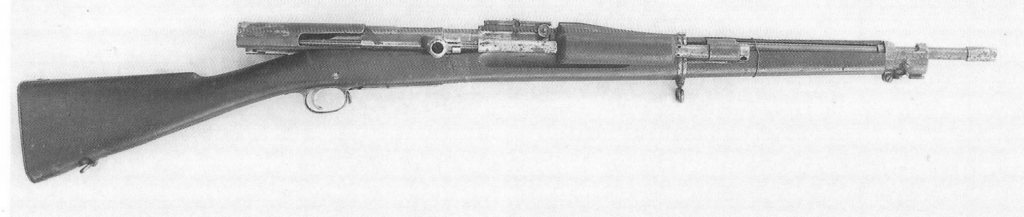

The next designs would only emerge in 1911, as Austria-Hungary would be having a competition for semi-automatic rifles. Siegmund Martineks conversion consisted of a gas-system attached to a Mannlicher M1895 fed by an offset magazine using Mannlicher’s clips. It was of relatively simple construction as the straight-pull bolt system of the Austrian rifle would lend itself well to semi-automatic actions. The other inventor, Michal Karl, had patented a semi-automatic rifle of his own design in 1910. In 1912, he built a hybrid gas-operated recoil system attached onto another service rifle which used gas pressure to lift a flap on top of the barrel to cycle the weapon. Franz Kretz, previously mentioned, would in 1913 also provide an M1895 converted to use the same type of system that he used on the Lee-Enfield rifle.

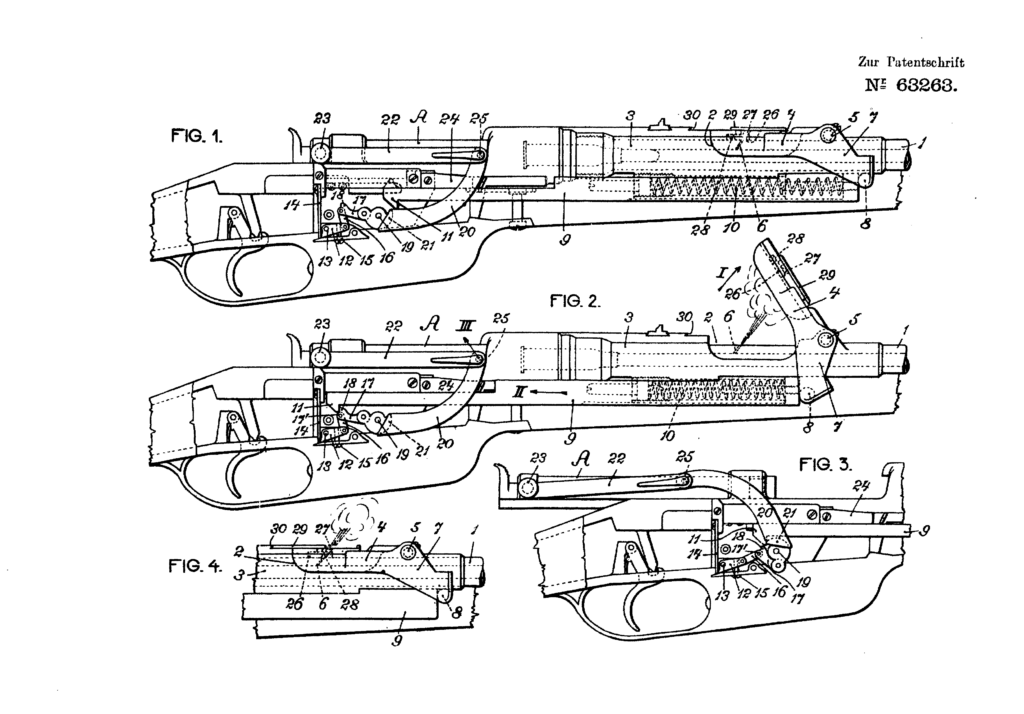

Finally, on the 28th of July 1914, Austria would declare war on Serbia which ignited WWI. With that came a realization that the stockpiles of machine guns weren’t enough to support such a modern conflict. Designers like Kretz and Ignaz Shrnitsitsa would provide the Austrian Army with machine guns based on older Mannlicher rifles which were outdated at that point, mainly the Mannlicher M1888.

The United States joins the semi-automatic craze

At the turn of the 20th century, the commanding officer of Springfield Armory contacted the Chief of Ordnance to suggest that the United States should buy and test examples of semi-automatic rifles being developed in Europe at the time. This attracted the attention of many civilian inventors who thought they could develop a capable semi-auto rifle for their country.

One of them was W.D. Condit who submitted a patent in 1905 for a Gas-Operated M1903 Springfield conversion. His rifle would be tested in the same year and feedback was promptly given, however for some reason Condit did not re-submit any modification of his system in the following years.

The American next attempt would be by Franklin K. Young who dabbled with a more unique form of semi-automatic mechanism. He would patent a Springfield 1903 conversion in 1902 that used a primer-actuated system to cycle the firearm, although, only in 1910 was the rifle actually tested by the Ordnance department. The rifle was subsequently modified to remove 23 parts of the original design and it was noted that his system used three fewer springs than the standard 1903 rifle. Young continued developing his rifle and in 1913 his final prototype was tested by Springfield Armory.

The third conversion would be the Hammond & Darlington, a gas operated, modified M1903 Springfield. The Ordnance Department tested their rifle in 1909 and found many negative points. To add to that, it was seen as too expensive of a conversion, costing about $35 per rifle.

Despite the previous failed attempts, the Rock Island Arsenal presented a rifle by a foreman named Woodbury which modified the standard M1903 with a gas piston attached to the side of it. The rifle was tested in 1913 and it failed after firing only two rounds. Then came the Murphy-Manning, built in Springfield as a competitor to the Woodbury rifle, tested in 1915 – although I have not been able to locate any information about its performance. Later in 1916, Rock Island would again attempt to convert the U.S. magazine rifle and now Springfield Arsenal would join in the trials. Both guns were gas operated and would be tested in Springfield. John Moses Browning remarked to Julian Hatcher after he was shown the two conversions that they reminded him of two mouse traps rather than semi-automatic rifles.

In 1917 and 1918, two more rifles would be made. Joseph C. White, working for the White-Greenman Arms Company, patented his means of converting the standard American service arm of WWI in 1917. Tested in the same year, the results were promising for his semi-automatic rifle. Pedersen’s device for the Mk.I Springfield rifle, the M1917 Enfield and even the Russian Mosin-Nagant is the most well-known conversion of the period, as it was planned on being used in the 1919 spring offensive that never came to be. The standard bolt mechanism of the Springfield M1903 would be replaced with a straight-blowback system, in .30 Pedersen, when the command to attack was given.

Honorable Mentions & Addendums

Other countries, while interested in developments of the conversion ideas, were more interested in adopting a newly developed semi-automatic rifle. France, for example, started their trials in 1894 and finished them in the 1910s with the limited adoption of the Meunier rifle. Not many were produced and when push came to shove in the Great War, Gladiator provided a partial conversion of the Lebel rifle with the RSC 1917 rifle and Delaunay-Belleville manufactured a Berthier conversion using a gas impingement system.

Germany, hoping that Paul Mauser would provide them with a suitable semi-automatic military rifle, did not incentivize other weapon factories to submit their own rifle systems. They were however, interested in testing developmental self-loading rifles of other European countries, those including Gewehr 98 conversions like the Swedish Sjögren around the 1910s and the Austrian Franz Kretz rifle in 1913.

Neutral countries like Sweden and Switzerland also developed their own self-loading rifles. The Friberg-Kjellman rifle and the Sjögren were top contenders in European automatic rifle development. Sjögren, in 1909, modified an M/1894 Swedish Mauser carbine to work with his inertial system. Switzerland had the Stamm-Saurer rifles, the Mondrágon being produced at SIG and the Rychiger rifle which was a short-recoil M1911 Schmidt-Rubin conversion. The Rychiger, even being tested abroad in the United States, being further modified by Major Elder.