By Frank Iannamico

During World War I the widespread use of machine guns was creating a stalemate in the largely trench war conflict thus becoming suicidal to attempt any infantry attack on the enemy’s position. Seeking a solution to the situation, the British came up with the idea of building a new type of vehicle that would be impervious to machine gun fire, and therefore able to attack and overrun the barbed wire and enemy trenches while taking only limited casualties. The vehicle would need armor to repel small arms fire and tracks to enable it to cross the muddy battlefields and trenches without getting stuck: it was named the Land-Ship.

The task of actually designing the machine was given to the British firm of William Foster & Company Ltd. The project was carried out with the utmost secrecy and the vehicle was given the code-name “tank” to conceal its true purpose from enemy spies. The first prototype land-ship was demonstrated to the Land-Ship Committee on 11 September 1915. As with most new designs, the land-ship took a few years to develop into an effective fighting machine. Once fielded during September 1916, the new British vehicles with their 12mm thick armor hulls were impervious to machine gun and small arms fire though the slow moving machines were vulnerable to artillery fire. One of the first documented successful fielding of the “tanks” was at the battle of Cambrai, France in November of 1917. The British plan was to use a combined arms force of air, infantry and tanks to assault the German lines. The Germans were able to stop some of the tanks by separating them from their supporting infantry and firing machine guns into the slits used by the crew to see out of the vehicle. Many other tanks broke down due to mechanical problems and were abandoned by their crews but the concept of the tank assault was considered a success.

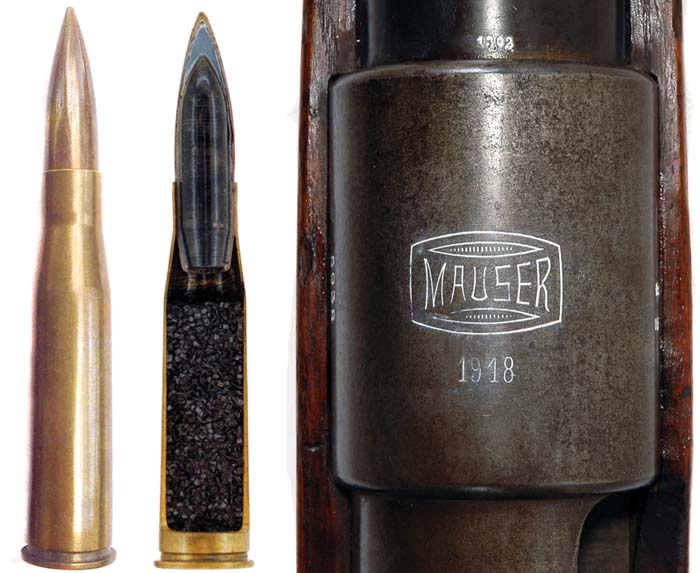

Following the British lead, the French introduced their new Renault FT 17 light tanks into the battle during 1917. The Germans quickly realized that they needed something to deal with the growing number of allied tanks and set out to provide their infantrymen with a portable anti-tank weapon. The concept of using a large caliber, high velocity machine gun, designated the TuF or Tank und Flieger, which translates to “tank and airplane”, as a means of defeating aircraft and armored vehicles was already under development in Germany. On October 25, 1917, the Infantry Department of the German Kriegsministerium (war ministry) had decided on a high velocity cartridge with a 13mm armor-piercing bullet. The resulting 13x92Rmm (rand or rimmed .525 caliber) T-Munitions armor-piercing round was developed by the German firm Polte-Magdeburg. The overall length of the round was 5.25-inches. The 802-grain (average weight) boattail bullet had a steel core, a GMCS jacket (Gilding Metal-Clad Steel) and a 200-grain powder charge resulting in a muzzle velocity of 785 meters per second (2,575 fps). The cartridge case was designed with a tapered case to ease extraction after firing. The cartridge was capable of penetrating armor up to 20mm thick at a range of 100 yards and 15mm thick armor at 300 yards, making it very effective against the rather thinly armored British tanks of the day. While the large-caliber Maxim type machine gun was undergoing development an expedient weapon was needed. The Mauser company proposed a large caliber bolt action rifle that would fire the new 13mm round. The weapon designed and built by Mauser was designated as the Tank Abwehr Gewehr or Tank Defense Rifle. Although effective, there were a quite a few disadvantages associated with the new weapon.

The first Tank Abwehr Gewehr weapon to be developed by Mauser had an 86cm (33.85 inches) long barrel that had a wall thickness of 8.5mm at the muzzle. The weapon weighed 17.96kg (39.6 pounds) with an overall length of 158cm (62.2 inches). Further testing and development revealed that the wall thickness of the barrel could be reduced and the barrel length increased for additional muzzle velocity. The early weapon was designated as the kurz (short) model. Production was limited consisting of approximately 300 units.

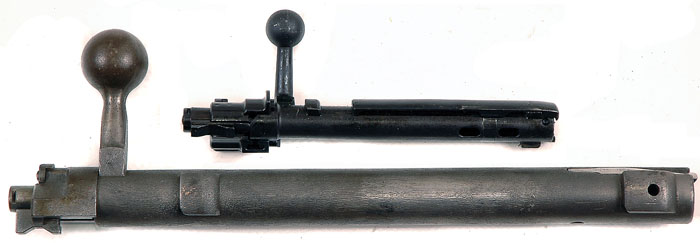

A later version of the Tank Abwehr Gewehr, now with the name shortened to the T-Gewehr, was fitted with a thinner (4.5mm wall thickness at the muzzle) and longer barrel than the earlier T-Gewehr kurz. The production T-Gewehr was a large, single-shot weapon that looked much like an oversized K98 German infantry rifle. The T-Gewehr had an overall length of 170cm (67 inches) and weighed 16.9kg (37.25 pounds); the barrel itself measured 98.43cm (38.75 inches) in length. The weapon had a removable 30.5cm (12 inches) high bipod that added another 1.81kg (4 pounds) to the overall gross weight. There was also a bracket located on the front barrel band to permit the weapon to be mounted on the T-Gewehr or MG 08/15 machine gun bipod. The receiver is approximately 13.5 inches long and 3-inches in diameter. The bolt is approximately 14 inches in length with a diameter of 1.25 inches and weighs 5 pounds. There was a version of the T-Gewehr produced that had a five-round box magazine, but production was very limited. After the war the allied intelligence reports stated that approximately 16,500 T-Gewehr rifles were produced.

The size and weight of the weapon made it difficult to carry. The stock was made of wood with a pistol grip to aid in controlling the weapon and there was no buttplate or recoil pad. The buttstock is made from two pieces of wood that are dovetailed and glued together. The receiver was marked with the Mauser banner and the year 1918. There are German proof marks located on the barrel and receiver, indicating that the weapon satisfactorily passed the hardness analysis, assembly testing and final fit. The proofs are a crown icon with a letter beneath it identifying the inspector who examined the weapon. The rear sight is a tangent leaf style calibrated from 100 to 500 meters.

The T-Gewehr is a large bolt-action rifle; the bolt head was designed with four large locking lugs that travel in slots machined into the inside walls of the receiver. When the bolt handle turned into the battery position the bolt is securely locked by the lugs to the receiver. The 35.56cm (14 inches) long bolt body has three 4.8mm gas vent holes on the right side and one 7mm vent hole on the left side. There is also one 6.4mm hole through each of the forward locking lugs. When the bolt is fully retracted it is held in the receiver by a catch located on the left side. A safety lever is located at the rear of the bolt and rotating the lever to the right side places the weapon on safe by moving the cocking piece off of the sear and blocking the firing pin.

After the weapon is fired the cartridge case is extracted as the bolt handle is rotated 90-degrees and pulled rearward. The extractor is spring steel and rests in a slot machined in the bolt. A long spring-loaded ejector lever pinned to the receiver initiates the ejection of the spent case. The lever rises upward after the bolt passes over it and ejects the spent cartridge out of the weapon. The trigger mechanism is an uncomplicated design and works in concert with the nose of a sear. The sear is held upward in an engaged position by a spring.

Generally, there were two to three anti-tank rifles issued per regiment. The T-Gewehr was fielded by a two-man crew: one man carried the weapon and several rounds of ammunition while the second man carried the bulk of the ammunition and bipod. For personal defense each crew member was issued a sidearm. The report and recoil of the German anti-tank rifle, having no type of recoil pad, buffer or muzzle brake like modern large caliber weapons of its type, proved to be physically demanding on its crew. After firing its first few rounds the T-Gewehr crew would immediately draw fire from the allied tanks and infantry. A number of T-Gewehr weapons were captured by the allies during the war but they were of little use because the Germans didn’t field any large numbers of armored vehicles. After World War I ended, the Treaty of Versailles banned the use of the T-Gewehr and similar large caliber weapons by the Germans. Many military historians believe that the Germans hid large numbers of T-Gewehr weapons, and continued to manufacture 13mm ammunition after the war ended. This theory is based on the large quantities of 13mm ammunition with a November 1918 headstamp, despite the fact that the war ended on 11 November 1918. It is believed that the Germans continued to stamp old dates on the cartridges to conceal production from the Allied Control Commission.

After the initial fielding of the T-Gewehr by the Germans, the general staff of the American Expeditionary Force expressed an urgent requirement to the U.S. War Department for the development of a high-power, large caliber weapon with armor-piercing capabilities. The proposed weapon was primarily to serve as an anti-tank as well as an anti-aircraft gun for ground forces. In the early spring of 1918, the British began development work on a large caliber cartridge based on the 13×92 millimeter German round. By April of 1918, U.S. General “Black Jack” Pershing, the commander of the American Expeditionary Force, cabled the War Department to report that British efforts on the project were progressing too slowly, and suggested that independent work be undertaken in the United States to develop a large caliber round. The American Expeditionary General Staff recommended the use of a projectile weighing approximately 670 grains with a minimum muzzle velocity of 2,700 feet per second. Eventually the British developed the .50 caliber Vickers round that had a projectile weight of 565 grains and a relatively low muzzle velocity of 2,520 feet per second. The United States Ordnance Department, along with the combined efforts of Winchester and John Browning, eventually conceived their own .50 caliber (12.7x99mm) cartridge and the famous M2 Caliber .50 Browning machine gun, which is still in U.S. service today and has had the longest continuous service life of any U.S. weapon. The .50 caliber Browning is in the military inventories of 86 countries today.

While the concept of the anti-tank rifle was short-lived primarily due to rapid advances in armor design, the German T-Gewehr provided inspiration for developing many similar large caliber weapons.

Disassembly of the T-Gewehr is accomplished by first insuring the weapon is not loaded. Rotate and slide the bolt handle rearward; then press the bolt catch on the left rear side of the receiver to release the bolt from the receiver. The stock is removed by first removing the wooden pistol grip, and then removing the three screws that secure the trigger guard. The front band is removed by driving out its steel retaining pin, and sliding the band forward.

(Special thanks to the following for their valued assistance: Michael Free for the use of his T-Gewehr for photographs and study; Michael Heidler, Germany and Bill Woodin, Woodin Laboratories.)

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V13N4 (January 2010) |