By Michael Heidler

The numerical and alphabetical manufacturer’s codes on German ordnance items have always been a topic of interest to collectors. But what was the reason for the secretiveness that lasted till 1945?

The well-known letter codes of World War II are the result of various marking and encoding attempts that started during the times of covert rearmament. The cause was the acceptance of the Versailles Treaty (28th June 1919) by the Weimar Government. Article 168 states: “The manufacture of arms, ammunition and war equipment of all types may only take place in workshops and factories, of which the location has been made known to and approved by the Governments of the Allied and Associated Powers. These Governments reserve the right to limit the number of workshops and factories. Within three months after effect of the current treaty all establishments for manufacture, preparation and storage of arms or the production of relevant designs shall be closed. The same applies to all arsenals except the ones for storage of the permitted stocks of ammunition. Within the stipulated period the personnel of aforementioned arsenals shall be made redundant.”

By acceptance of the ultimatum of the Allied Governments of 5 May 1921, the set list of future suppliers of arms, ammunition and war equipment on the part of the German Government, according to Article 168 of the Peace Treaty, was established. It contained 13 companies for Army material and 28 companies for Navy material.

The permitted armament for the Reichswehr was precisely defined in Article 180 of the Peace Treaty as, for instance among small arms, 84,000 rifles (Mauser 98 system), 18,000 carbines (Mauser 98 system) and 1,863 machine guns. Surplus weapons had to be handed over to the Allies (although they often disappeared) and new developments were forbidden.

Eminent German armament companies like Mauser had to convert their production to consumer articles, whilst the Allies approved the relatively inexperienced Simson company of Suhl as the sole producer of pistols, rifles and machine guns – probably with the deliberate intent to weaken Germany militarily.

In the following years German industry was under constant scrutiny by the Allied Control Commissions. Some companies managed to emigrate to or establish branches in neutral countries. For example Rheinmetall-Borsig AG covertly took over the Schweizerische Waffenfabrik Solothurn AG and, from 1929, developed there fully automatic weapons again. Other companies like Henschel, Krupp, Junkers and BMW opened offices in Russian factories as part of the German-Russian cooperation.

Besides the already mentioned activity abroad, (former) defence contractors were not idle within their own country. This was made easier by a steady diminution of the allied control activity and an increasing interest by the German military. A precise time for the start of the secret rearmament cannot be given exactly, but it would seem that by 1925 capacity was reached that necessitated the introduction of covert production marks.

Confirmation is given by a decree of the Army Weapons Office of 12 December 1925 that begins with the words: “By the above referenced Decree company markings for non-permitted arms companies were introduced.” Presumably at that time every officially permitted company was allocated a code marking. Four of which today are known to have been used as a basis for the covert rearmament programme are:

| P Rdf Rhs S | for Ammunition, all types for Powder & Explosives for Fuses & Fuse bodies for Carbine parts | (Polte, Magdeburg) (WASAG, Werk Reinsdorf) (Rheinische Metallwarenfabrik, Werk Sömmerda) (Simson & Co., Suhl) |

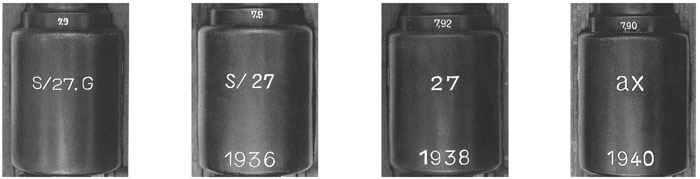

This basic code letter was supplemented by a code number that stood for the actual – but in fact illegal – manufacturer. Thus, the headstamp code “P131” on a 9mm cartridge case identifies the manufacturer as DWM in Berlin-Borsigwalde and not, as it was intended to overtly indicate, Polte in Magdeburg. The same goes, for instance, for K98k rifles with the codes “S/27.G” and “S/27” that were actually manufactured by ERMA in Erfurt, not by Simson & Co. in Suhl.

The same 1936 letter from the Army Weapons Office, goes on to indicate that disguise for powder manufacturers no longer seemed necessary. The code numbers were to be substituted by an abbreviation (usually of the manufacturer’s location): “The requirement for covert marking of deliveries of the powder and explosives factories with the Rdf. covert designation, after removal of disguise, is no longer required, therefore the introduction of official company abbreviations takes effect immediately.” With that the requests of the Weapons Office Departments for Evaluation and Acceptance for cancellation of the code marks were granted.

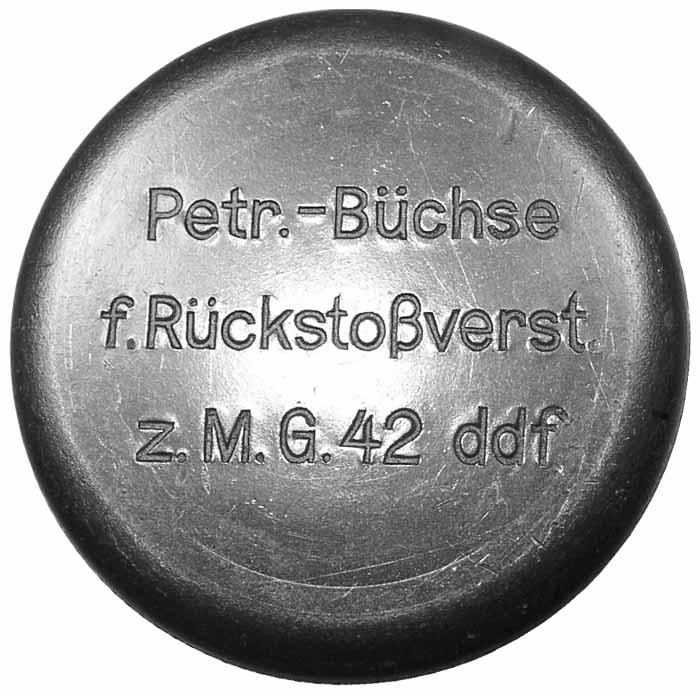

After the allocation of code numbers had reached 999, in April of 1940 a completely new code system was introduced consisting of up to three lower-case letters. This system presumably arose through the allocation of letters to the suppliers of K98k parts, the so-called Saxony Group, on the 28th of October 1938. Due to the relatively small size of numerous parts, marking with three letter codes was not possible. In these cases the companies concerned were assigned single letters to be stamped 1.6mm-2.5mm high on metallic and 6mm high on wooden parts.

The one letter system appears to have started a whole new encoding system based on code letters. With that the final form of all code systems was determined. A letter from the Army High Command from the 1st of July 1940 gives information about the new production marks for powder and explosives manufacturers: “The manufacturing marks for powder and explosives factories are made up like the other production marks of a three letter group of small letters so that these marks do not stick out by appearance amongst the bulk of other coded manufacturing marks. To ease memorizing of these production marks by the qualified personnel they will not be sought out at random as is done for reasons of secrecy for the other production facilities, but will be made up in conjunction with the official denomination of the manufacturing facility.”

Due to secrecy the lists of code assignments were copied in very limited numbers and unfortunately only 15 original volumes remain. The letter combinations “paa” – “zzz” are untraceable and it is doubtful if all combinations were ever used.

The remaining volumes were issued as follows:

| Letter Block | Date of Issue | |

| aaa – azz baa – bzz caa – czz daa – dzz eaa – ezz faa – fzz gaa – gzz haa – hzz jaa – jzz a – zz October 1941 kaa – kzz laa – lzz maa – mzz naa – nzz oaa – ozz | November 1940 February 1941 March 1941 April 1941 May 1941 June 1941 July 1941 August 1941 September 1941 October 1941 June 1942 September 1943 December 1943 August 1944 October 1944 |

Subsequent to the first issues, additions, alterations and deletions were made from time to time, but were not all passed on. In some cases the final production or assembly plants began to investigate who their suppliers were, since the code identities were kept secret even from them. In 1944, the Mauser company tried to find out the identity of its suppliers with the help of a survey, but not all companies answered the questionnaire and so the resulting list showed large gaps. In contrast to the three letter groups the one and two letter codes leave some questions which have yet to be answered. Although the “aaa”-“azz” groups were already issued in November of 1940, the volume containing “a”-“zz” appeared in October of 1941, although the single letter codes of the Saxony Group had been in use since 1938.

Other Code Systems

Beside the aforementioned code systems there were other less common systems, which were not always meant just to deceive.

The Reichsbetriebsnummer

A further type of labelling was the Reichsbetriebsnummer (State Manufacturing (Plant) Number), like the RBNr. 0/0020/0053 for the company Oster & Co. in Königsberg or 9/0750/5184 for the Franck’sche Verlagshandlung W. Keller & Co. in Stuttgart. The origin of these numbers in the late stage of the war is controversial, especially since the term sounds more civilian than military. One reads of different sponsors (from the Air Force to paramilitary formations) but this is only speculation, so long as documentary proof is missing. In addition, hardly any of the numbers have been identified. The lowest known numbers were given to companies in Eastern and Western Prussia, followed by Upper and Lower Silesia, Brandenburg, Saxony, Pomerania and the area of Berlin. The further distribution took place without any recognisable order.

The System of the Reichszeugmeisterei of the NSDAP

In contrast to the half-hearted attempts of the Air Force and Navy, that led to no result, the Reichszeugmeisterei (State Master of Ordnance) of the NSDAP (Tegernseer Landstr. 210, Munich), which had been founded in 1929, developed its own coding system. After 16 March 1935, a branch identity letter, a product group number, a company number and sometimes the production year were labelled on items. The branch identity numbers stand for

| “A” “B” “D” “G” “H” “K” “L” “M” “V” “W” | for equipment manufacturers for cotton fabricators for service-clothing manufacturers for wholesaler for trade representatives for clothes retailers for leather fabricators for metal processors for sales outlets for wool fabricators |

The metal manufacturers for example were subdivided into 12 groups:

| M 1: M 2: M 3: M 4: M 5: M 6: M 7: M 8: M 9: M 10: M 11: M 12: | insignias, medals dependent subsidiaries of bigger manufacturers emblems, badges, symbols belt-buckles accessories for uniforms (stamped eagles, buttons, etc.) aluminium products knives, daggers metal products convention badges musical instruments NSDAP-awards NSDAP-miniature-awards |

Thus, the code “M7/40/38” on an NSKK enlisted man’s dagger, for example, means that the end manufacturer “40” was the forge of Carl August Hartkopf in Solingen, the item itself was from the category “M7” – knives and daggers, and was produced in 1938. Besides this marking, the RZM-logo was also applied. From March 1945 all suppliers to political organisations of the NSDAP were allotted a RZM number that they had to mark on all items delivered instead of their company logos.

Because only fragments of this system remain today, only a few codes can be assigned without doubt, also due to the numerous variations: the most current list is given above. In some cases the codes were supplemented with SS, though then the first segment is missing (as, e.g. 36/40 SS). It is assumed that these items were ordered directly by the SS from the respective manufacturer.

It is interesting to note that companies concerned now had to cope with dual codes in production, depending on the recipient organisation: HJ proficiency badges of the G. Brehmer company in Markneukirchen are stamped “M1/101” whilst other items for the Army from this manufacturer dating from the same period have a “eyb” marking.

Reaction of the Allies

The German code system did not stay undetected by the opposing intelligence offices. Therefore one can constantly read that supposed specially trained teams were attempting to decode the codes. Apart from that the codes could not be decoded mathematically due to their random assignment, no proof of these decoding attempts exists.

Undoubtedly, the Allies were intent to know the various locations of the German arms industry – the centers (ball bearings, oil, heavy industry, etc.) of which were already long known, which could be seen by the numerous bombing raids. To what extent the German code system in conjunction with the relocation of production was successful and whether it influenced allied actions cannot be judged here, since too many events and information still lie in the dark.

New Book About The Secret Armament Codes

Although this topic has been dealt with before, the extent and utility of previous treatments has not been complete in the existing literature. The new book Deutsche Fertigungskennzeichen bis 1945 from the German author Michael Heidler, resulting from long term research, will serve all collectors and military historians as a primary reference.

For the first time it is now possible to determine not only a manufacturer’s name from amongst the 9,300 codes listed, but also the codes of specific manufacturers from their name. Companies that underwent a name change during the course of the war are listed under both their original and their new names. A failing, even in the original, contemporary reference lists and consequently in subsequent literature is the use of incorrect locations. Due to the primary attention paid to the manufacturer name, mistaken locations have been passed on from author to author since WWII. For this reason each location has been checked and verified using maps contemporary with the original war-time code allocations and the respective modern federal or national abbreviations and other useful notes have also been added. Additionally, for many of the non-German locations the current modern name is also given, since the original (often German) names cannot be found on modern maps. If known, the old address is also listed. Following survey of numerous equipment items, weapons and ammunition and after evaluating documents from primary sources such as regional and national museums and archives, the items produced and marked by many manufacturers have also been identified.

Every attempt has been made to refer back to original contemporary documents in this book in order to correct the multitude of translation, transcription and misinformation errors which exist in the lists of codes which currently circulate among collectors.

The book has more than 500 pages and contains pictures of rare documents never seen before. Very helpful for foreign readers is the bilingual written part about the development and use of the different code-systems in German and English language.

Price incl. postage in Europe: 37,- EUR

Price incl. postage worldwide: 60 USD (by airmail)

Payment is accepted by bank-transfer, Paypal or in cash

For book orders please contact the author:

Michael Heidler

Eschenweg 45

89555 Steinheim

Germany

eMail: GGBuch@web.de

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V16N2 (June 2012) |