By George E. Konits P.E.

The instant his front and rear sights were aligned with the bull’s-eye, he squeezed off a round. Clearing the fired case, he raced to examine the target. This time he was trying a new sabot, designed to come apart immediately upon exiting the barrel, allowing the fléchette to fly on its own. His face fell when he saw the target. The elongated hole was proof positive the fléchette was tumbling end over end. Maybe it was because there were no fins. Surely a phonograph needle was not the ideal fléchette. If only he could watch the projectile in slow motion! He was sure he could easily have figured out a solution.

In spite of this failure, he was certain this would be the direction for ammunition of the future. The year was 1934, and the shooter was a fourteen year-old named Irwin Barr. Win, as he preferred to be called, was no stranger to experimentation with firearms and explosives. Only recently had he finished working off his punishment for detonating a homemade explosive charge in the basement. The force from the blast blew pieces of the linoleum away from the floor of the kitchen, located just above. Win was surprised at the magnitude of the explosion, considering he had gleaned the blasting powder formula from a well-known bomb maker’s manual, The Encyclopedia Britannica.

For much of his youth, Win’s heroes were inventors, with gun designer John M. Browning and engineer Nikola Tesla heading the list. He added Thomas Edison after visiting his laboratory, not far from Win’s home in Linden, New Jersey. Win had a creative mind, artistic talent, and a keen imagination. He spent most of his spare time drawing and building models of bombs, tanks, guns, and aircraft and his boyhood dreams included designing all of the small arms for the U.S. military. Deciding on a technical career after high school, he entered the two-year program at the Casey Jones School of Aeronautics in Newark, NJ. His choice of schools stemmed from two factors: His father, a family doctor, had died when Win was 16, leaving insufficient money for Win’s college tuition. Casey guaranteed an engineering job to anyone who completed its rigorous program. Win accepted the challenge and became one of the few attendees to succeed in that challenge.

Excelling in all of his engineering and drafting courses, Win completed the Casey program and found employment at the Glen L. Martin Company (today after multiple mergers known as Lockheed Martin). Win worked in Martin’s “bull pen” among other designers and engineers in an ocean of drafting boards. His assignments involved creating extensive layouts on huge sheets of drafting paper. Using a pencil and a drafting machine in designing aircraft gun turrets and aircraft was slow and tedious, as was using tables, charts, and slide rules in making structural and aerodynamic calculations.

In many respects Win was a traditional engineer, using tolerance analysis and engineering computations rather than “cut and try” to improve the chances of a first-time success. It was a different culture in those days. It was engineering based, innovative excellence that was the real driver for everything. Where Win differed was in his approach; it was always innovating, always pushing the technology envelope as far as it would go. Often, he didn’t solve a problem, he defined it.

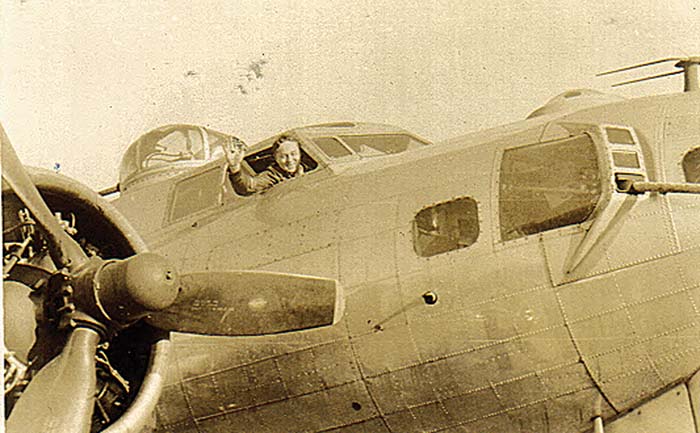

In 1944, Win left Martin to serve in the Army Air Corps. Because of his experience, Private Barr was assigned to the Dover Air Force Base in Delaware to work on rockets and rocket launchers. His successful rocket launcher design was slated to be demonstrated for U.S. and British military personnel. The design had been demonstrated previously but at the last minute Win decided he could shorten the time between launches. His untested new design exploded during the demo and Win learned an important lesson that lasted a lifetime – never demo anything that hasn’t been thoroughly tested. In spite of this setback, the rocket launcher, in its original configuration, was standardized and Sgt. Barr was recognized with a commendation medal. While still in the Army, he continued his fléchette experimentation at home, using the flame from his gas range to heat the heads of sewing needles before hammering them to form one pair of the fins while fashioning the opposing pair from a piece of razor blade.

When the war ended, the Glen L. Martin Company welcomed Win back, promoted him to armament engineer, and gave him a new challenge: to work as Group Engineer on America’s first liquid fuel rocket, the Viking. Others working on this project included a German expatriate named Werner Von Braun and Robert Goddard, the inventor of inertial guidance. Von Braun must have been surprised by Win’s rejection of the rocket steering technology, which the Germans had used successfully for their V2. Instead, Win and two of his co-workers favored a gimbaled rocket engine and jet controls for roll, pitch and yaw. The three were awarded a patent for their successful design innovation, whose method is still used today as the preferred means of steering rockets.

Working for Glen L. Martin was interesting particularly after the success of the Viking rocket system, but Win and some of his fellow engineers had other ideas. They wanted to work on guns and gun-related projects, not on aircraft alone. As these interests were not on the Martin agenda, the splinter group left to form Aircraft Armaments Incorporated. This new company would focus on research and development to encourage the most advanced thinking in the defense industry.

Win and his partners invested in an 80-acre tomato farm in Cockeysville, just north of Baltimore, MD. It was an ideal location, close enough to customers in the Washington, D.C., area, yet far enough away to have firing ranges and expansive R & D facilities. Their venture almost ended in disaster when the military unexpectedly shifted its interest to arming aircraft with missiles and no longer wanted guns in turrets. Fortunately, the fledgling company secured some contracts developing tank turrets and was able to sustain the business.

At 30 years old, Win had a mind that couldn’t stop inventing, self-confidence bolstered by his success in rocketry, and the Army-adopted rocket launcher. Due in a large part to Win’s hard work and influence, Aircraft Armaments Incorporated enjoyed success after success. Win not only came up with many unique armored vehicle innovations, during this time inventing the long rod penetrator and puller sabots which increased by tenfold the ability to penetrate armor, he also invented a lightweight amphibious tank, a new vision block, and high-strength bearings for heavy-load application. Wisely, Win insisted on patenting every one of his inventions, helping to secure the future of the company he helped found.

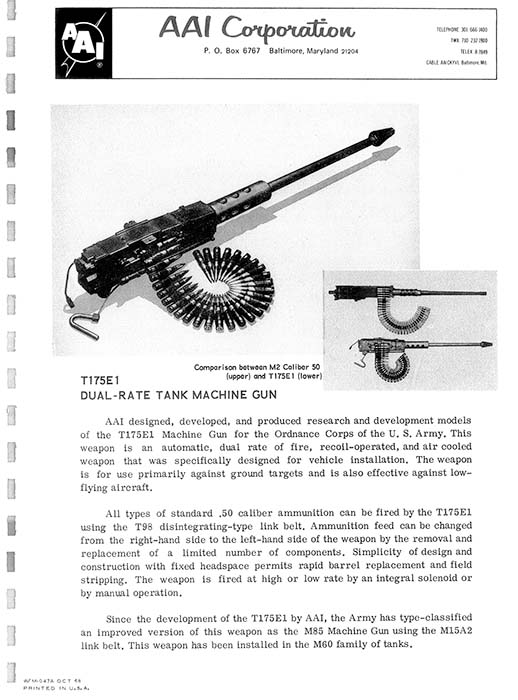

An early challenge faced by AAI (the name now shortened after a “no brainer” naming contest) was to assist Springfield Armory in the design of a new .50 caliber machine gun. Opportunities for innovation included the call for a Browning cycle with an extremely short receiver to enable the gun to fit within the tiny cupola of the new M60 main battle tank. A new push-through link replaced the rearward end-stripping link of the M2. The customer insisted on a dual-rate weapon – low rate for tank application and high rate for short-time on-target applications – and the resulting weapon was successfully designed and designated the M85 machine gun.

At the end of WWII, military studies showed that a lightweight rifle system was desirable for use in concert with an onboard grenade launcher. In 1951, the Army initiated its SALVO program, which sought a weapon firing multiple projectiles to increase hit probability; requiring not only a lighter weight rifle but also lighter weight ammunition. Here, Win Barr thought, was the perfect opportunity to further develop his all but lifelong dream – a fléchette firing rifle. Although Win could not interest the Army in the AAI approach at that time, he remained convinced he had the best solution and pursued further development of the fléchette model with in-house money.

As pressures increased at work, tragedy struck on the home front in 1957 with the sudden death of Win’s wife. His AAI partners and their families provided sympathy and support as Win handled this loss. A widower with four children, he remarried in the fall of 1959 and, with his wife Dorothy, moved the family to Lutherville, close to AAI’s Cockeysville headquarters.

In the mid 1960’s, Win’s responsibilities grew when AAI was awarded a development contract for the M203 grenade launcher. Eliminating the stand-alone launcher, the AAI grenade launcher would give a platoon a grenadier without the expense of losing a rifleman. The military’s 1968 adoption of the M203, along with its adoption of the M85, was a great source of pride for Win and his team. During this same timeframe, Win initiated the development of an underwater pistol and the construction of an important asset for AAI, an underwater firing range.

When the SALVO project was terminated, the Army replaced it with the Special Purpose Individual Weapon program (SPIW). This time AAI did receive government funding, and the timing was perfect because now Win had the ballistic stability information he needed for the projectiles. It was no coincidence that the fléchettes fired in Win’s XM19 rifle had a strange resemblance to the Viking missile, because Win used the Viking’s wind tunnel test results in their design. AAI had competitors, of course, but the accuracy of the XM19 could not be equaled. While the burst fire effectiveness was significant, the failure to meet single shot accuracy requirements at long range was the principal reason the project ended

At the same time the XM19 was in development, AAI worked on a 22mm cannon for the new armored personnel carrier, which today is known as the Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle. TRW introduced a gas-operated candidate designed by Gene Stoner while General Electric offered a recoil-operated cannon. These competitors offered traditional approaches, but that was not the case for AAI. Win sought the reliability of gas operation but didn’t want the troublesome gas residue that he knew would foul the weapon. He achieved this by using a unique ammunition concept with a primer that acted as a piston to power the weapon. He had successfully deployed this system on the SPIW and adapted it to a cannon sized weapon. Other weapons used a variation on this ammunition design – a closed piston pusher so gas did not escape from the cartridge. This concept was used on underwater pistols, grenade launchers, and special weapons for clearing enemy tunnels in Vietnam.

During his tenure as Vice President for R & D, Win had fine-tuned his philosophy and his means for motivating his engineering staff. When he became AAI President in 1969, in the course of his typical 10-hour day, he would work his way through the entire plant, from the lathes and mills to the firing ranges and engineering offices. At any time, pretty much anyone could expect a visit from Win, who always was eager to discuss progress on each project, to offer encouragement, and, above all, to help infuse new ideas. He also became known as the only head of a major corporation whose office featured a well-used drawing board.

Win often worked out design solutions by sketching them on paper. He would then turn the paper over to rough out some quick calculations that verified the new approach would work. If you were gone by the time Win got to your work area, you could expect to find on top of your desk one of these sheets or a simple note with Win’s directions on how to proceed. To the credit of Win’s managerial skills, nobody recalled feeling pushed or needing to push back. They all respected Win’s abilities and wanted to be a part of these unique opportunities for technical innovation.

Win was soft-spoken – but insistent. As long-time members of the engineering staff independently reported, you could tell him anything and he would consider what you said. Then, with a quiet intensity, he’d charm you into believing his way was the best, as it so often was.

Win’s fascination with advancing the state-of-the-art in tank design was manifested in a new lightweight, low-profile, air-droppable tank. It would be hard to hit, provide maximum protection to its crew, and carry 60 rounds for a rapid firing cannon. At the outset, AAI designers of the T92, as it was eventually designated, got carried away and drew up a vehicle much larger than Win had envisioned. One evening after everyone had left; Win studied the huge pencil drawing that had taken draftsmen many hours to produce. He took out his ball point pen and, at a point about 2/3 of the way along the vehicle’s length, drew a bold vertical line through the tank, and left a note saying: “Make it this long.” Although the drawing was ruined and had to be restarted, the results were dramatic. The technical innovation of this vehicle found a home in the Israeli Merkava tank and the French AMX-13 after the T92 was beaten out by the problem-plagued M551 Sheridan.

While excellent development opportunities arose with the military, there were slow times to be dealt with. This was never a problem for Win, who was a virtual fountain of fresh ideas. Solar power, for example, was an underdeveloped energy source that warranted exploitation. Surely, with Win’s ideas and a few calculations, there could be a business opportunity or two for AAI. Win selected one of his top engineers, Tony Farinacci, and gave him a project – to design a solar and wind-powered cooling system for brine tanks used in cheese-making. Tony had plenty of experience with weaponry, but was no expert on solar or wind power, or cooling systems. Without hesitation, Win sent Tony back to school to learn what was needed. This was typical of Win, always wanting the best equipment and the best people to do the job. If they didn’t have the right preparation or the right skill set, getting it was only a matter of time and money. For Win, it was worth every penny. The solar energy endeavor eventually found success at the Reedy Company in Orlando, whose solar roof design provided electrical power for years until the mirrors succumbed to the Florida sun and lost their efficiency. A large number of patents on the roof and building design for solar energy collection were awarded to Win during this time.

In the late 1960’s Win began thinking seriously about remotely piloted vehicles. In 1958 he filed for a patent on a flying saucer that was years ahead of its time. Its unique design required sophisticated computers to manage the controls. This stands as one of the few designs in Win’s lifetime where the technology had not yet advanced far enough to allow his design to work. Little did Win know that his efforts then would be the beginning of a major product line for AAI. Today, AAI’s Shadow Tactical Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (TUAV) serves as an intelligence-gathering workhorse for coalition forces in Iraq and Afghanistan.

By 1970, in business for 20 years, AAI had grown to 1,000 employees, almost a full third of whom were engineering staff. The company’s goal remained the same: boundary-pushing research and development for military and commercial markets. At this point, two thirds of AAI’s income came from non-armament projects that included hydraulics and material handling systems. Typical examples of AAI’s successful design innovations include the training systems for the Apollo space program, crew station trainer and lunar module procedures simulator, a unique cutting tool for the space station, and a destruct system for the Saturn rocket.

All AAI engineers were expected to evaluate the stress levels of components they designed while at the same time making them as lightweight as possible. Often this meant designing with a low margin of safety, which sometimes led to failure. Win was not overly disturbed when he learned of part failures because he knew his teams were staying on the technological edge, keeping weights as low as possible. It should come as no surprise, then, that Win was a big fan of maraging steel – an ultra-high-strength steel with high cobalt content. Any time a design is boxed into a corner where the part cannot be made on a larger scale, this is the steel that can save the day. At the other extreme, Win hated torsion springs. In spite of the book calculations that predict safe stress levels, these springs are famous for breaking at the retention arm and are often avoided by gun designers.

In July 2010 I arranged for a visit to AAI for the purpose of interviewing Tony Farinacci to gather firsthand knowledge about Win Barr. When I arrived, I was surprised to find that Paul Shipley, Steve Miller, Ron Christ, and Dennis Trump had heard about the interview and insisted on joining us to contribute their experiences working with Win. This eventful meeting brought out a lot of information about Win and a litany of the many small arms projects he influenced. These include the AAI 6mm Squad Automatic Weapon, 4.32mm Serial Bullet rifle, Caseless Advanced Individual Weapon System, 12 gauge Combat Assault Weapon, TriCap shotgun, 5.56mm Advanced Combat Rifle, and completion of the development of Picatinny Arsenal’s .50 caliber Dover Devil.

I asked the group to give me some insights into Win’s personality and what it was like to work with him. They all agreed that Win loved his work and valued the people who worked with him. He never asked anyone to work harder than he did and spent most of his vacation time at work, rather than play. Win loved the Bahamas, and did find some time to visit and even buy property there; planning a retirement that could include developing a small business to employ the locals. Usually his Bahamas trips were short, except for the time a water skiing accident put him in the local hospital. Win had no patience for languishing in a hospital bed, so he arranged for a steady stream of AAI engineers to fly to the Bahamas in order to review their projects and to get new marching orders.

Much of our discussion centered on Win’s humanitarian side. Before he retired in 1989, he invented a heart pump and a steerable catheter for use in heart operations. Decades earlier, Win had invented a special tear gas grenade with a dispensing method that was less likely to start fires. They told the story about Win’s young son Alan who one day heard his dad sobbing in another room and asked if he was all right. Win told him not to come in, explaining that he was testing tear gas and wanted to try it on himself rather than risk anyone else being harmed.

Win’s excitement about projects was contagious; he loved to share his observations, thoughts, knowledge, and new ideas with anyone in the company who would listen. Janitors on the second shift, often the only ones around for Win to share his ideas with, spent many an evening lending an ear, even if their understanding was sometimes minimal.

An accomplished artist and photographer as well as a visionary engineer, Win Barr distinguished himself in the development of aircraft, vertical lift aircraft, rocket launchers, guns, solar power, military tanks, spacecraft, watercraft, and space technology. He committed most of his designs to patents available to all for study, touching on fields of medicine and energy as well as aerospace and defense. A man considered ahead of his time and a tireless worker who cultivated confidence and curiosity in his workforce, Win discovered how to increase his efficiency by building a company, filling it with top-notch technical talent, and leading his teams to solve critical problems.

In a sense, Win successfully “cloned” himself through his engineers, setting an example and using his persuasive skills and managerial expertise to get ideas rapidly developed. In the 1990s, AAI formally adopted Win’s not so secret method for motivating people to do their best: Employee Recognition. Among the annual coveted honors, the Win Barr Award for Innovation recognizes the AAI engineer or engineering team demonstrating the greatest degree of innovation and creativity.

Inducted into the Ordnance Hall of Fame in 1985, Win received numerous awards throughout his thirty-eight years with AAI, including the ten years he served as President and Chief Operating Officer. To mark Win’s retirement in February, 1989, a host of AAI colleagues, personnel, clients, representatives of local government and industry, and officers of virtually all branches of the U.S. military participated in the nearly three-hour ceremony. For one, General Alfred M. Gray, then-Commandant of the United States Marine Corps, gave Win a standard-issue helmet, making him “an honorary Marine,” saluted, and presented a Certificate of Commendation which concluded, “Mr. Barr’s total service to the Defense Industry in key executive positions and industry committees exemplifies the highest traditions of distinguished service….”

Before his death in 2005, Win’s life’s work yielded more than 200 patents, the majority of which he had proven feasible, successfully built, and tested. Today, AAI continues the same quest for innovation, producing and developing small arms and new products for the military and other industries. Working under Army contract to create caseless ammunition, the company’s forward-thinking engineering teams recently distinguished themselves by designing the Lightweight Small Arms Technologies (LSAT) machine gun that fires case-telescoped ammunition – a timely invention in the Barr tradition.

There at AAI, the spirit of our Renaissance man Win Barr lives on.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V16N4 (December 2012) |