By Peter Murray

During the period between the World Wars Rheinmettal’s Solothurn plant in Switzerland developed what has been called the Rolls Royce of submachine guns – the Steyr Solothurn MP34(ö). These guns are comparatively scarce, so when I came across several I took the opportunity to examine a couple of them in detail.

German Tacticians recognized the limitations of the bolt-action rifle in close combat relatively early on during the First World War. By 1915 they were calling for a short-range assault weapon with full-automatic capabilities. Various experiments such as the fully automatic Luger and Mauser C96 were tried and rejected before the development of the first practical submachine gun, the MP18. The concept of the submachine gun proved to be a success, but it arrived too late to have a major impact on the war effort.

The Treaty of Versailles at war’s end imposed a total ban on German submachine gun development and production and limited their use to police service. One way around this was the use of foreign subsidiaries, and through this expedient several German firms were able to continue their work with submachine guns. Rheinmettal’s MP34(ö) was one of a series of submachine guns developed during this time.

Like the other early German submachine guns the MP34(ö) is a development of the MP18 concept and at first glance the resemblance is striking. It has a similar stock and barrel shroud, and a magazine protruding from the left side. It has entirely different safety, selector and operating mechanisms, however. Developed at the Solothurn plant in 1925, it was made there until 1929 when Steyr took over production until manufacturing time and costs became prohibitive. The last examples are said to have been made in 1940, although there are date-stamped examples from at least as late as 1942. The gun was adopted by the Austrian military and police as well as being exported to Portugal, Yugoslavia and Japan. Although issued on a limited basis to German forces the maschinenpistole 34(ö), for Austria , was never adopted officially by that country.

After the war literally tons of military equipment, including thousands of weapons were crated and shipped off to Russia. Some of it has been hidden away in storage depots ever since. My work there provides access to some of this material. When I came across crates labeled “pp Var.Shteyra” in faded Cyrillic lettering I wasn’t sure what to expect. They turned out to hold a number of MP34(ö)s that had been packed in pairs with some spare parts and stored presumably since the end of the war. Except for being completely dry of oil, the two I examined were in very good condition with bright chambers and bores. Date stamped 1942, they were presumably made for export since they had the Steyr logo instead of the military codes “660”or “bnz” assigned to Steyr during the war, but they also had German military acceptance marks (WaA 189) in a number of places. Each magazine was stamped with both the proof and the Steyr logo. The serial numbers were in the low 2000 range.

The gun operates on the open-bolt blowback principle common to virtually all weapons of this class, relying on the return spring and the weight of the bolt to counteract chamber pressure. It’s a select-fire weapon with a cyclic rate of 550 to 600 rpm.. The barrel length is a fairly short 7.8 inches and the overall length is 31.8 inches. Its loaded weight at 10.87 pounds compares favorably with the Russian PPSh41 at 12 pounds and the much lighter looking MP40 at 10.37.

The MP34(ö) uses a staggered-column, detachable box-type magazine holding 32 rounds with lips angled to accommodate the forward angle of the magazine in the well. Magazines have indicator ports numbered for every eight rounds, although the first two ports are hidden inside the magazine-well. The release is on the rear of the well, so a magazine can be changed while still pointing the weapon. Magazines can also be reloaded by inserting them into a slot in the bottom of the well and feeding rounds from stripper clips through the top. It sounds clumsy, but it’s very convenient and fast, provided you have the right stripper clips; 9mm NATO clips don’t fit at all, Russian clips are perfect, and standard M16 stripper clips can be used in a pinch. Using the Russian clips we were able to load three magazines in less time than it took to load a single MP40 magazine using the MP40 reloading tool.

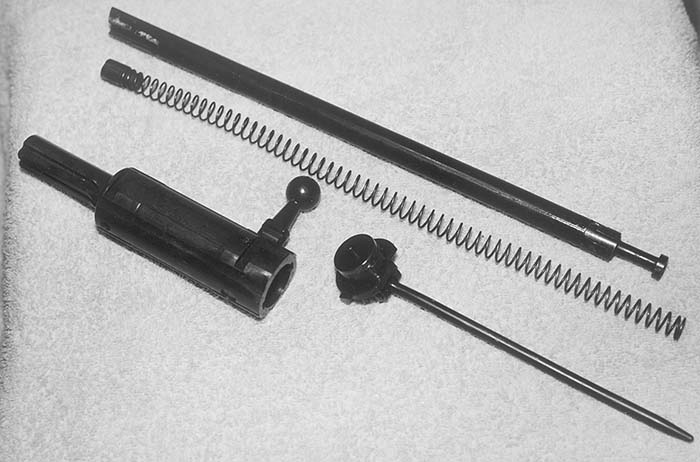

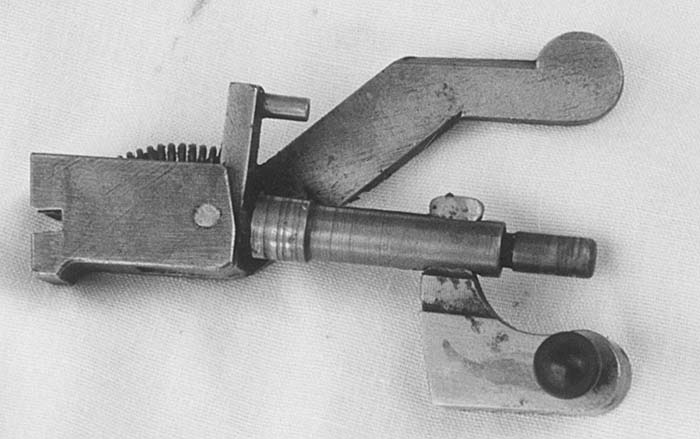

The cocking handle is located on the right of the receiver and is reminiscent of a bolt action rifle. The bolt is a complex affair with a “rat tail” guide that runs down through the recoil spring tube in the stock. There are two sears. The trigger sear catches the bolt and holds it back for semiautomatic fire. The selector sear depresses the trigger sear so that the bolt can run freely for full-automatic fire. The selector itself is inletted into the left side of the stock.

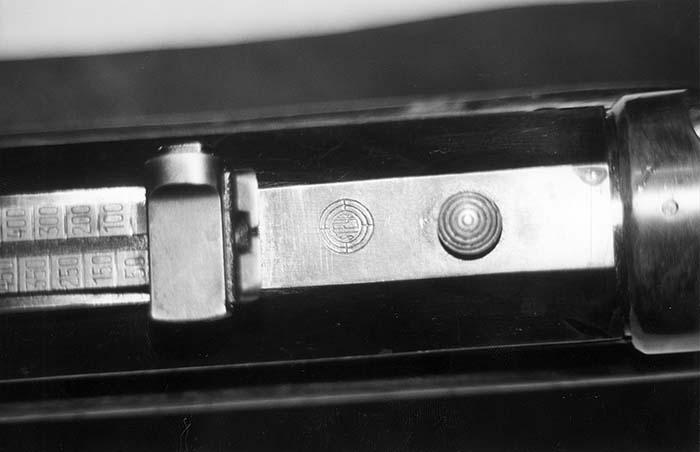

The safety is mounted on top of the receiver, immediately in from of the rear sight. Moved forward, it engages a slot in the top of the bolt that prevents it from advancing to fire. In order for the safety to be engaged, the weapon must be cocked and ready to fire. All open-bolt weapons are prone to accidental discharges, so they safety should be engaged any time the gun is cocked but not actually being fired.

The sights are a typical V-notch rear sight, very optimistically calibrated for 50 to 500 meters and a large squared front sight inside curved wings that can be adjusted for windage with a drift punch. A bayonet lug is mounted on the right side of the barrel shroud. It’s inconvenient because it was designed for the Austrian Mannlicher bayonet rather than the German model and shooting the gun with the bayonet attached lowers the point of impact considerably, but it’s unlikely that it was ever used anyway. It can be removed with a screwdriver once the barrel is taken out.

So, what’s it like to fire? It’s a well-balanced weapon that points well. The sights are typical of most submachine guns; the sight radius at 14 inches has to be short because of the barrel length, and the front sight is a square block of metal that tends to obscure the target at anything beyond 50 meters. Although the stock is grooved on the right side to accommodate the shooters off hand, the guns overall length makes it too short for this to be of any real use. Shooters will find grasping the barrel shroud just in front of the magazine-well much more natural. Anyone inclined to hold onto the magazine-well or the magazine itself will find the gun not only shooting down and to the left, but doubling the size of its groups. This is not a gun for southpaws. For left-handed shooters the most natural place for the right hand happens to be right over the ejection port, and even gripping the shroud further forward only works well when firing from the shoulder. Holding the gun any lower can result in hot brass bouncing off your arm and over your shoulder or far more distracting, sliding up inside your sleeve. With the magazine release and the selector on the left, the safety on top of the receiver and the cocking handle on the right, you would have to be pretty familiar with the gun to feel comfortable with it in any kind of an emergency situation.

Both weapons were fired with 9mm 124-grain ball ammunition. The first shot from any open-bolt weapon is always a bit disconcerting because of the movement and time lag as the bolt runs forward for the initial shot. The action on both of these guns, however, was very smooth, much more so than either the PPSh41 or the MP40. Combined with the overall weight it made for a very light recoil and little muzzle climb. Trigger pull was relatively long, but smooth and even. Anyone who is at all familiar with submachine guns knows they are not target rifles. From a bench position one of our 5-round groups on semiautomatic impacted into 3.25 inches at 30 meters and another into 5.75 inches at 50 meters. Full-automatic fire doubled the size of the groups. So the 500-meter sights aren’t very realistic, although for a short range assault weapon the accuracy is acceptable.

To sum up, it’s accurate enough for its class of weapon. The sight radius and front sight perhaps leave something to be desired, but in action submachine guns are pointed more than aimed anyway. Left-handed shooters will have to make some adjustments, but it’s very pleasant to fire once you get over the initial sensation that the whole gun might topple over to the left if you don’t hold up the magazine.

To fieldstrip and clean the weapon, remove the magazine and make sure the chamber is empty. The receiver is hinged and lifts from the rear to allow the bolt to be removed and the barrel cleaned, but the safety has to be off and the bolt fully forward before this is done. The release pin at the rear of the receiver is a weak point. It must be depressed with one hand at the same time the receiver catch is pushed forward with the other, and since it’s a threaded pin about 2mm in diameter it’s prone to bending and breaking. Of all the weapons we looked at, only one had a straight release pin. Once the receiver is lifted, the bolt and guide can easily be pulled back and removed. The guide rotates and slides out of the bolt so that cleaning them is a simple enough matter and with them removed the barrel and interior of the receiver are readily accessible. Re-assembly is just a matter of reversing the steps in field stripping. The bolt must be placed fully forward, though, and care must be taken once again with that receiver release pin.

For more extensive cleaning or maintenance the weapon can be disassembled with a set of screwdrivers and a 12mm wrench. Once the gun is field stripped, a screwdriver can be used to remove the trigger guard, the selector and the return spring, which is taken out through a trap n the buttplate. The trigger and selector mechanisms will then slide easily out of the stock. Removing a set of screws at the rear of the receiver allows the stock itself to be taken off. Even the barrel is changeable. It has an integral nut at the front. On both of our weapons removing and replacing the barrel was a simple operation requiring a 12mm wrench, a vice and only a slight amount of torque. A lip on the barrel ensures that it is seated to a satisfactory depth, although any work of this kind should always involve proper headspacing by a competent gunsmith.

Each weapon was issued with two leather pouches, the first containing three extra magazines and the second cleaning accessories and spare parts. Both have the tongue and button at the sides rather than at the front, making them unhandy at best. There is no magazine loader because the loader was built right into the receiver, somewhat pointless for German troops, who were not issued 9x19mm ammunition in stripper clips. The final accessory was the bayonet for those times when the bad guys are just too close to shoot.

Submachine guns and their accessories are expensive propositions for any collector, and this one is no exception. MP34(ö) don’t have the celebrity of some other SMGs, but their reputation and limited availability compensate for that. A spare extractor, firing pin and return spring are always good investments, and an owner can count on having to replace that release pin more than once in the guns lifetime. Some parts and accessories are available from IMA in New Jersey. Their kits are fairly expensive, but they provide everything but the lower receiver, including a good barrel, which can be used to rejuvenate a worn-out weapon far easier than in any other submachine gun. A note of warning; the MP34 was produced in several different 9mm calibers (and even in 7.63mm Mauser). Owners should check weapons and barrels carefully before using them for the first time.

Relatively few MP34(ö)s were produced and the gun was soon eclipsed by the MP38/40 series, so its historical impact has not been great. Although it may have been part of a technical dead-end in weapons development, it represents a period of early submachine gun manufacture when quality was still an ingredient in military weapons production. Strong and pleasant to fire, it is very well made to extremely high standards. It’s the Rolls Royce of it class.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V7N1 (October 2003) |