By Michael Heidler; Photos courtesy SA-KUVA, Jarkko Vihavainen

Since World War I, flamethrowers have had a permanent place in the armament of many armies. In the far north, however, there was no need for them – until the Russian invasion in November 1939, when the Winter War broke out.

In autumn 1939, the Soviet Union had demanded that Finland cede a large part of the Karelian Isthmus and other territories. After Finland refused the demands, the Red Army attacked the neighboring country on November 30, 1939. Although vastly superior in numbers and material, the Russians made only slow progress against the stubbornly fighting Finns, which avoided open field battles and used the rough terrain for guerrilla methods to inflict heavy losses on the enemy from ambush.

Flamethrowers would have been a helpful weapon for the battles in the dense forests and against the fortifications that were mostly built from wood. But the Finns did not have any. Since it had to be done quickly, they searched the international market and found what they were looking for in Italy. There, the military used the portable Lanciafiamme Spalleggiabile Modello 35 and the Italians agreed to sell 176 of them to Finland. However, the units arrived in Finland too late to be used. Despite all the fighting spirit, they could not permanently withstand the Red Army and the war ended in mid-March 1940. By then, only 28 flamethrowers had been delivered; the rest were still on their way by ship.

The Finnish Liekinheitin M/40 Solution

After the ignominious peace with their dangerous neighbor to the east, the Finns wanted to remain on guard. The Finnish army introduced the Italian flamethrower as the Liekinheitin M/40 to its engineer battalions. It consisted of two tanks, each divided horizontally. The upper chamber contained the propellant (nitrogen) and the lower one, the incendiary agent; 6 liters (1.58 gallons) of fuel oil, each. When filled, the flamethrower weighed just under 23 kilograms (50.7 pounds).

The ignition at the front of the lance was electric, either via an 18-volt dry battery or a high-voltage inductor. One charge could deliver 20 to 30 bursts of fire lasting one second. However, only at a range of about 10 to 15 meters (30 to 50 feet). If the maximum range of 20 meters (65 feet) was used, the number of possible bursts dropped rapidly.

The Finnish pioneers practiced intensively to get to know the device and to develop suitable tactics for its use. Very quickly, it became clear that the tanks should be filled shortly before use. The system was never completely leak-proof at 20 atmospheres, and the longer the waiting time, the shorter the duration and range of the operation. The electric ignition also caused considerable difficulties in humid conditions. Due to the weight and location of the valves, the operation of the M/40 flamethrower always required a second man.

Despite some shortcomings, the flamethrower proved to be a useful support weapon. And the practice soon paid off, because on June 25, 1941, the so-called Continuation War against the Soviet Union began. Finland strove to regain its lost territories.

Russian ROKS-2

It was during this renewed campaign that the Finns first encountered Russian flamethrower units. Their ROKS-2 model was first mentioned as booty in a military brochure from September 1941. Subsequently, more and more devices could be captured, so that the Finns introduced the flamethrower as the Liekinheitin M/41-R. Even spare parts were produced, and major repairs were carried out at Arms Depot 1 (Asevarikko 1) in Helsinki. In action against its former owners, the Russian model was much more popular and reliable than the Italian one.

In terms of appearance, the ROKS-2 does not correspond to a typical flamethrower. The Soviets had tried to disguise it as a rifle. The lance was embedded in the converted wooden stock of a Mosin-Nagant rifle, using the original rifle sling and with ignition by pulling the trigger. The two incendiary tanks on the back stretcher were covered with sheet metal to simulate a backpack. The bottle with the propellant hung crosswise under the box.

Whether this camouflage was really useful in practice is doubtful. The enemy soon got to know the device and the bulky sheet metal covering of the nozzle and the thick hose to the backpack could hardly be overlooked. And for the Finns it brought no advantage anyway, since the Russians knew their former possession very well. Towards the end of the war, the Finns also captured a few copies of the simplified ROKS-3, on which the tanks were no longer covered.

When filled, the ROKS-2 weighed about 23 kilograms (50 pounds), and also required two men to operate. The Soviets used special ignition cartridges made from standard 7.62x25mm cartridge cases. The propellant tank could be filled up to 115 atmospheres and gave the flamethrower an enormous range of 30 to 45 meters (98 to 147 feet) with about six to eight bursts. This also depended on the type of filling because the Finns used two different mixtures depending on the season: in summer 66% heavy fuel oil and 33% highly flammable fuel oil. In winter, 55% heavy fuel oil, 30% highly flammable fuel oil and 20% petrol.

Liekinheitin M/44 Upgrade

The two flamethrowers M/40 and M/41-R served the Finnish army well. They were feared by the enemy – and therefore became priority targets on the battlefield. Because of the total weight and the lance, the operator could only carry a pistol for defense. He was, therefore, always given a second man with a submachine gun at his side. Nevertheless, the situation remained unsatisfactory and the losses high.

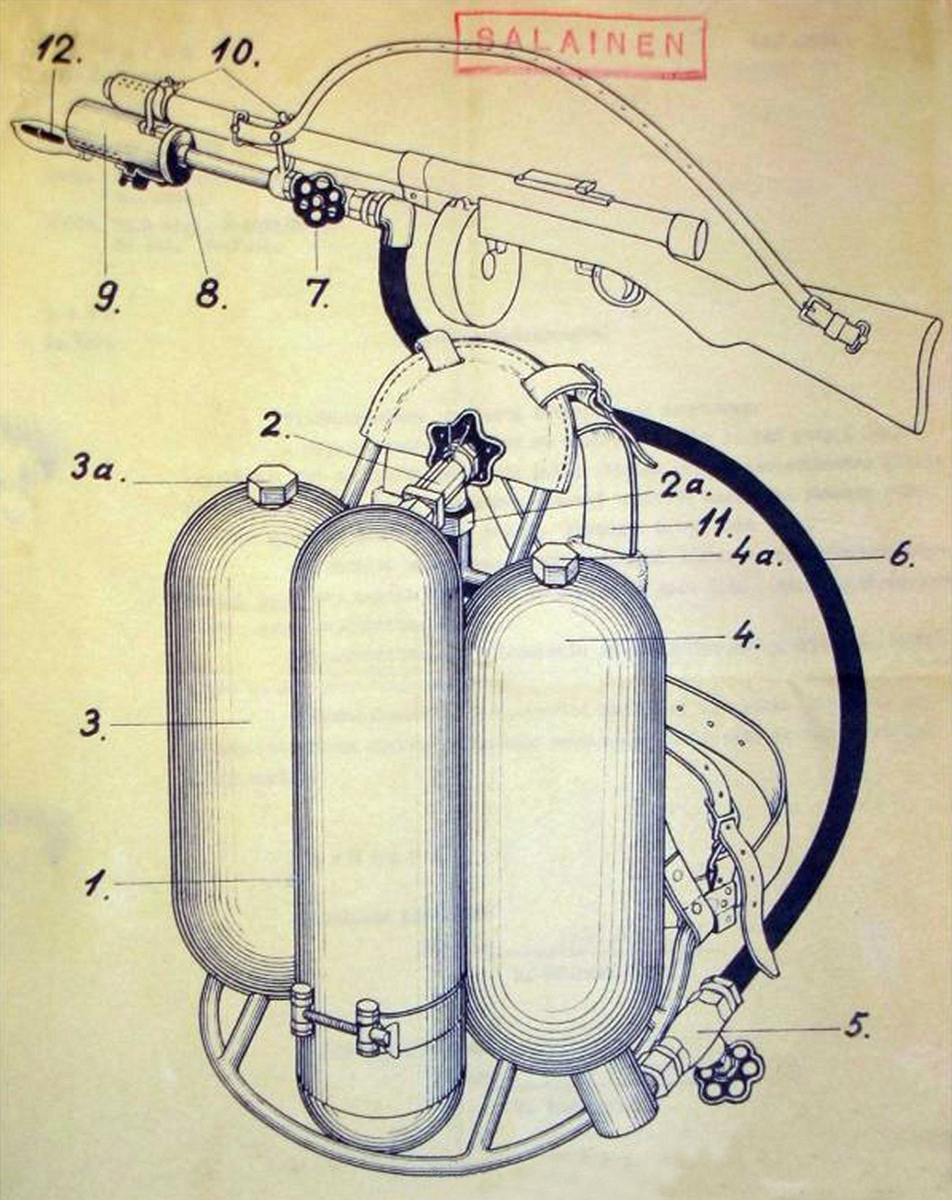

To overcome this shortcoming, Sergeant M. Kuusinen of Infantry Regiment 1 designed a combination weapon. He combined a light flamethrower with the Suomi KP/-31 submachine gun. The structure of the flamethrower corresponded to the usual composition of tanks for incendiary and propellant agents. But the lance was now attached with a pair of clamps under the barrel jacket of the fully functional submachine gun. The flamethrower was initially called Liekinheitin M/Kuusinen and was renamed Liekinheitin M/44 when small series production began.

Battlefield Performance

Since Finland had few resources for developing its own weapons, Kuusinen’s idea came in very handy for the army. The Suomi KP/-31 did not require any modifications. A first prototype was successfully presented at the headquarters of the Finnish Armed Forces in April 1944 and led to approval for further development. This was followed by the production of a small series for intensive troop trials with cavalry, engineer, and tank units. The feedback was predominantly positive. The main criticism was the limited range: the flamethrower managed a total burning time of up to one minute or 50 to 70 short flame bursts. But only up to about 10 meters (33 feet.) That was considerably less than the two models that had already been introduced.

When fighting at short range in trenches or urban areas, the advantages of the M/44 became apparent: long endurance, comfortable carrying, and lighter weight. But such situations were rare. Most combat took place at longer distances and the power was not sufficient to cover that much ground. Moreover, the pilot flame on the nozzle burned permanently after the first ignition. During the first combat deployment of three prototypes with Pioneer Battalion 35 on the night of August 16, 1944, the Finnish attack unit was therefore discovered too early. Nevertheless, the operation near Loimola (Karelia) was ultimately successful and the men of the flamethrower squad were decorated for it.

The Finnish Army initially ordered components for 100 M/44s with a delivery date of July 15, 1944. Assembly was carried out by Arms Depot 1 in Helsinki. According to the few documents that have been preserved, only about 40 units were completed. At the same time, attempts were made to increase the range. A safety device in the form of a ‘dead man’s switch’ on the handle of the lance was also tested, so that the flame would go out immediately if the operator was injured or killed.

After World War II, flamethrowers played practically no role in the Finnish army. A small number were still kept by the border guards for training purposes and were scrapped in the 1970s. A few years after the war, Sergeant Kuusinen received a payment of 10,000 Finnish marks for his flamethrower design. Only a few examples of the Liekinheitin M/44 have survived in museums to this day.