Story & Photography by Seth R. Nadel

Czechoslovakia is a country with a long, long history of innovation in making arms. In fact, central Europe was at the very heart of firearms development from the start. While not every design was a success, the ones that were made history. The first in the modern era was the ZB26 and ZB30 light machine guns which evolved into the British BREN light machine gun. The BREN, originally in .303 British caliber, was modified to accept 7.62 NATO rounds and served from the late 1930s well into the 1980s. The most common Czech design seen these days started as the 9mm CZ 75 pistol, and variants are in use today in the U.S. for personal protection and high-level competition.

But the failure of a design can come from any number of reasons, including design flaws, changes in perceived needs and … political issues. The rifle we will be looking at here was a real innovation, strangled by purely political demands. Even in gun design, politicians and the demand for total uniformity have a say. Like it or not, the world evolves along political lines.

Evolution from Battle Rifles to Semiauto Carbines

The late 1940s and early 1950s saw major changes in the service weapons of the various countries. Keep in mind that the U.S. was the only country to issue a semiautomatic rifle to most troops in WWII. All the other combatants relied on versions of their WWI bolt-action rifles for their soldiers. While most countries had an overabundance of WWII rifles on hand at the end of the War, the need for less powerful cartridges and thus lighter, smaller rifles—carbines, if you will—to fire them had become clear. All sides entered WWII with rifles and ammunition that could reach 1,200 yards; after-action reports defined the battle space as much smaller at 300 yards or less. So the rifles were too big, too heavy and fired unnecessarily powerful rounds. Of course, there was no desire to lighten the loads of the troops (called “grunts” for a reason: it‘s the sound they make when they try to stand with all their gear), but with lighter guns and ammo, they could carry more ammo. A post-War study concluded that most casualties from small arms were not caused by aimed fire, so the conclusion was to put more bullets in the air and cause more casualties.

The Germans had led the way, with their Sturmgewehr assault rifle, using a shortened 8mm round. The Soviets, having suffered the most casualties in the War, paid attention and developed the 7.62×39 round, the SKS and later the AK-47 to fire it. The Russians had enveloped Czechoslovakia into their “sphere of influence” after WWII, bringing them behind the “Iron Curtain,” while allowing a pretense of self-control. The Czech arms designers pressed on, thinking their developments would produce a better rifle, regardless of who ran the country.

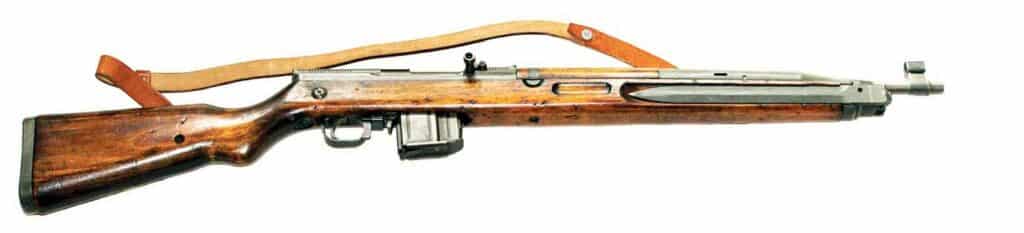

The M52/Vzor 52 (adopted in 1952) is commonly known as the “SHE,” for the three letters stamped over the serial number. What they mean is unknown. It was an interesting evolutionary step which was a contemporary of the Soviet SKS, and similar in many ways. Both rifles used 7.62 (.30 caliber) rounds but also different rounds. Both are gas-operated and load from 10-round magazines—detachable on the M52, fixed on the SKS. Both at one time or another were fitted with folding bayonets, permanently attached to the rifle. And both became side notes to other developments.

Design Factors

As noted, the M52 was designed around a 7.62 round—an intermediate round. But this round is the 7.62×45. The NATO round for comparison is the 7.62×51. The Czechs went for more powder space, and thus more velocity, than the 7.62×39. And, in a snub to the Soviets, it is NOT compatible with the SKS; it will not fit into the magazines, let alone the chambers.

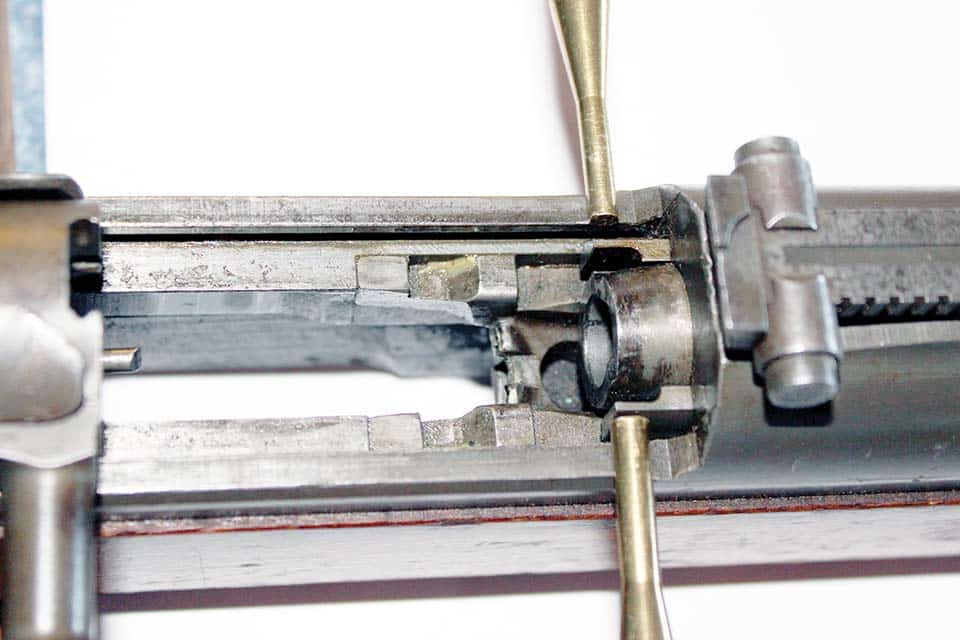

The rifle, while gas-operated, works slightly differently than the designs we are familiar with. It does not have an operating rod like the M1, FAL, M14, SKS and so many others. Nor does it have a gas tube like the M16/M4 family, currently so popular. It utilizes an annular gas cylinder concentric around the barrel, a sliding gas cylinder piston or sleeve and a sheet metal piece which moves the “actuator,” which imparts the impulse from the gas piston to the bolt carrier via two prongs at 3 o‘clock and 9 o‘clock. The use of two rather than one prong means the force is more evenly distributed to the bolt carrier. Thus, they avoided the twisting and wear issues found in the early piston-driven ARs. The sheet metal piece is formed as a close fit to the barrel, reducing the weight and height of the forend, while avoiding the problems of dumping the products of combustion into the bolt/bolt carrier.

In a fully automatic rifle, heat from full-auto fire and magazine dumps could become a problem, but the M52 was designed only as a semiauto with that small, 10-round magazine. Long before the heat retained on the barrel and the actuator could become a functioning problem, the wooden handguard would most likely burst into flames.

It uses a tipping, rather than a rotating bolt, with front locking lugs. All the M52s were fitted with a side folding bayonet—a poor idea, as most former infantrymen will tell you. Bayonets are used far more often for opening boxes and cans than stabbing the enemy, so the bayonets either get removed, bent, or the troops have to be issued a knife as well—even more weight to be carried around. The example pictured in this article still has its leather sling, and two spare magazines were found at a local gun show, priced right because the owner had no idea what rifle they fit.

The biggest complaint with the rifle was its all up weight of 9.5 pounds, almost as much as the .30-06 M1 weighs.

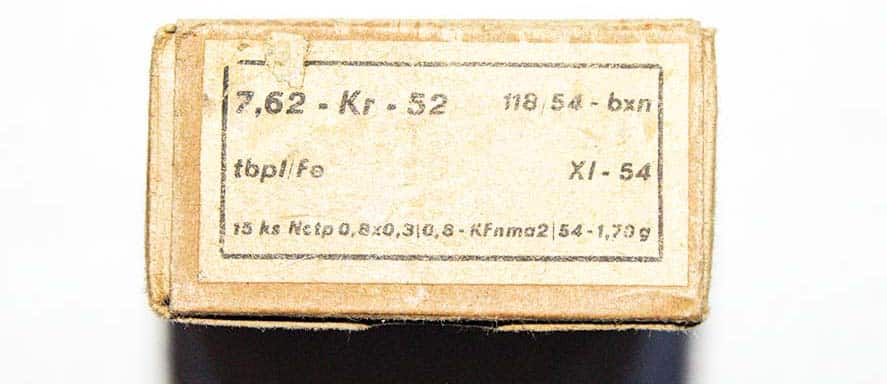

The 7.62×45 Round

The rear sight is marked up to a very optimistic 950 meters, which brings us to the cartridge. Most of the 7.62×45 ammunition found is in steel cases with a lacquer finish, with a few brass-cased rounds in small lots. The extra 6mm of cartridge length produced only 100 to 200 fps more velocity than the 7.62×39. It uses a 131-grain projectile.

Every round the author has fired has been a hang fire: the pop of the primer is followed by a 2- to 3-second delay before the powder ignites with a bang. The first time this happened was very disconcerting; these are the only true hang fires the author has ever experienced. Sadly, ammunition was only made for a few years, until the 7.62×39 was issued to all troops. Some, dated 1967, turned up in Grenada when we invaded. It is currently quite rare.

The M52 was only made for 5 years, before the Soviet Union lowered the boom and required all further guns to be in their 7.62×39 round, creating the M52/57, or just M57. It was identical to the M52 in all respects except caliber, and some M52s were converted to the Soviet round. This rifle only lasted 1 year before the M58 was introduced, a selective fire 7.62×39 rifle with a 30-round detachable magazine and an external resemblance to the AK-47.

The M52 was, as usual for the Soviets, passed on to client states such as Cuba and may occasionally be encountered in Africa. As long as they have a gun and a few rounds, nothing is discarded.

Why Was the Design Dropped?

Even in the U.S., good designs were sidetracked by the NIH (Not Invented Here) syndrome. Perhaps the most notorious was the 1941 Johnson Rifle, a recoil-operated .30-06 semiauto, which our Ordnance Corps bypassed by rushing the M1 Garand into production. John Garand worked for the Ordnance Corps, while Johnson was a lawyer and a U.S. Marine Corps Captain and thus was clearly not the “proper” type to design the new U.S. service rifle.

Equally ignored was the FN FAL when we switched from the .30-06 round to the 7.62 NATO round. The M14, a modified M1 designed by the Springfield Armory, was adopted by the U.S. The few other countries that adopted the M14 did so because they got it basically for free from the U.S. Yet 90 countries adopted the FN rifle and paid for it or for the rights to make it. That alone shows which is the better rifle, but politics overwhelmed quality on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

It is interesting to speculate on what an M52-type rifle would look like made with modern materials. With a polymer stock (and heat shields under the forend), the rifle could be more “tubular” in appearance. Without the gas block and tube (or piston) of the M16/M4 types, it could be quite svelte. Of course, the folding bayonet would go, and magazines would be larger. One feature that would be kept is the threads on the exterior of the end of the barrel and the thread protector. It would make it easy to fit a “sound moderator” (silencer).

Ultimately, the Soviet demand for uniformity killed the M52 and the 7.62×45 round. To the absolute rulers of the Communist Bloc, it made sense.

REFERENCES

W.H.B. Smith, Small Arms of the World, 9th ed.,1968, and 11th ed., 1977.

Gary Paul Johnston and Thomas B. Nelson, The World’s Assault Rifles, 2010.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V24N5 (May 2020) |