By Stephen C. Small, Ph.D.

Between the years 1870 and 1892, a tremendous technological change took place in the nature of the military service rifle. During that period the bolt-action magazine-fed rifle was refined and thereby transformed into a practicable weapon of war. By 1914, such weapons would become the standard service rifle for all the great European powers as well as for many developing nations worldwide. These rifles would retain a dominant status as the individual soldier’s weapon until eclipsed by the semiautomatic rifles of World War II and the auto-loading rifles that followed after the war.

The bolt-action rifle’s success as a military weapon came largely as a function of its practicality in combat. Two key reasons support this assertion: Firstly, its rapidity of fire – a key combat multiplier in war. Secondly, the bolt-action’s physical architecture possesses the requisite strength with which to handle intense breech pressures associated with the sort of ammunition made possible by the development of smokeless powder (a French invention of the late1880s). The strength of the rifle’s action proved decisive as high velocity small caliber ammunition possesses both a quick time of flight and a flat trajectory – both attributes enhance accuracy and thereby the probability of hitting the target.

The object of this essay is to sketch the circumstances and activities that attended the testing of bolt-action rifles by the U.S. Army in the 1870s and 1880s. In Addition, this essay offers an interpretation as to why the army’s adoption of a bolt-action rifle was for so long a decision deferred.

The Late 19th Century U.S. Army

The army was not a national priority between the years 1870 and 1892, nor was technical progress in the development of small arms a priority within the army. After the Civil War ended the Union’s million-man army of 1865 was trimmed to 27,000 by 1876 and would remain at that level until it spiked at the onset of the War with Spain in 1898. Army expenditures fell from $1,031,323,000 in 1865 to $38,177,000 in 1880. These reductions made investments in the modernization of the service rifle a challenge at best. As a result, soldiers of the late 19th century found themselves armed with product-improved conversion of a Civil War era rifle.

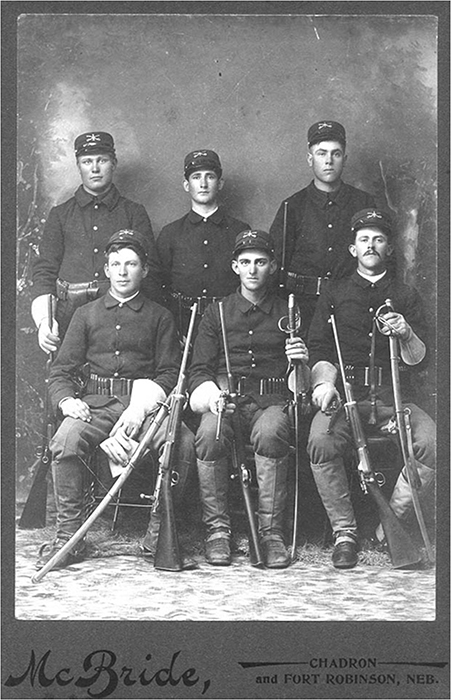

The mission of the post-Civil War army was diverse. Activities ranged from enduring the peacetime doldrums to surviving combat hardship. On the quiet side of army life were soldiers stationed along the eastern and western seaboards in coastal defense forts. They prepared to defend against enemy battleships raids – “terrorists-like” raids that were anticipated but never actually occurred. Other soldiers served as members of an uneasy occupational force in the Southern states, a peacekeeping mission that sometimes flared up into violence as freedmen, carpetbaggers, and defiant Southerners struggled for political power (this mission officially ended in 1877). Additionally, the army was involved in quelling domestic disorders and labor protests. However, the bulk of the army was garrisoned in 255 isolated outposts west of the Mississippi. These men were involved in an undeclared war with various hostile tribes and renegade Indians; an extended fight in which there were 27 military engagements between 1865 and 1890 in the West. As to the four major campaigns, they took place in 1867-69 and 1874-75 on the South and Central Plains; 1876-78 on the Northern Plains; and 1880-86 in Arizona and the Southwest. Small arms played a significant role in these Western wars as soldiers and their enemies were armed mainly with rifles, carbines, and revolvers as heavy ordnance was too cumbersome too haul across narrow trails, deserts sands and other forms of hindering terrain.

The Civil War Legacy Rifle

When the Civil War ended in April 1865, the army possessed a million or so serviceable, but obsolete, single-shot muzzle-loading rifles. Given the mid-century pace of technological change, the need for a modern breech-loading rifle was self-evident. Consequently, shortly after the war ended the Ordnance Department convened a rifle board. This board consisted of a council of officers whose object was the testing of promising new rifles – one of which might enter in candidacy for the army service rifle. When its work was concluded the board recommended that the Peabody breech-loading rifle be such a candidate. The rifle represented a quality design and was quite unique as it was one of the first rifles to utilize a dropping-block that hinged at the rear. No matter, budget conscious U.S. government Ordnance officers opposed the Peabody. Specifically, they recognized the prohibitive expense of retooling for a wholly new weapon at the Springfield Arsenal.

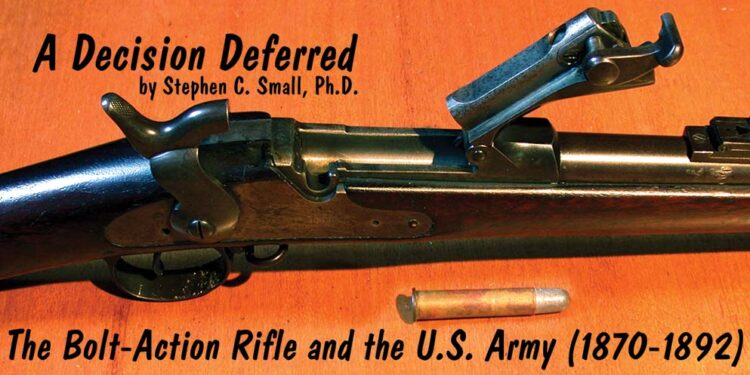

An economy-oriented solution was decided upon in lieu of the Peabody option. Existing muzzle-loading rifles were slated for conversion into breech-loading rifles. The Springfield Armory’s Master Armorer, Erskine S. Allin is generally credited with this modification to the legacy rifle (Allin served as the Master Armorer at Springfield Armory from 1853 until his death in 1879). Allin’s conversion entailed cutting into the rear-top of the barrel and installing a cam operated hinged block. This enabled the rifle to be loaded at the breech. The manner in which it opened gave the single-shot rifle the nickname: “Trapdoor” rifle. In the years that followed numerous modifications would be made to this rifle. However, the basic rifle would remain the army service rifle until 1892.

Despite its less than auspicious origin, the Trapdoor rifle turned out to be a practical and effective weapon of war. Most especially, it had a reputation of being an excellent long-range rifle, an attribute deemed quite important by soldiers who held that Indian warriors, while poor shots at long range, were outstanding fighters at close-quarter combat. Therefore, one’s life expectancy might hang upon keeping the hostiles at several hundreds yards standoff. The long-range capability of the Trapdoor rifle would seemingly give advantage to the soldiers.

A service rifle is only as effective as its ammunition. In the pre-smokeless powder era, the Trapdoor rifle’s bullet was quite formidable. Made of lead, it was round-nosed, flat-based, and its weight was approximately 405-grains. Propelled by 70 grains of black powder, it had an average muzzle velocity of 1,300 feet per second (fps). To enhance its wound producing effects, soldiers were encouraged to aim for the enemy’s midsection as abdominal wounds were usually fatal. The faith in the performance of the .40-70 cartridge was such that by the late 1870s the candidate bolt-action rifles were all tested in this caliber. However, the stopping-power came with a price. Recoil from this prodigious cartridge gave the Trapdoor rifle a more pejorative second nickname: “The mule kicker.”

Conservative Thinking

Army ordnance officers of the era were studying bolt-action rifle technology with a skeptical eye. This attitude was not necessarily born of ignorance. Well educated and equally well traveled, officers kept abreast of technological change. Nor were the qualities of bolt-action rifles outside officer learning. As early as the mid 1830s, Johann Nikolas von Dreyse of Prussia was making a practicable military bolt-action rifle. Additionally, the combat potential of these weapons had been demonstrated on more than a few European battlefields since mid century. Moreover, officers need not travel abroad to learn about the emerging technology. Domestically, commercial bolt-action rifles were being developed and marketed. Nevertheless, the bias against the bolt-action apparently ran deep. In the 1870s, Brigadier General and Chief of Ordnance (1874-1891) Stephen Vincent Benet said, “There seems to be some prejudice existing in our service against the bolt system and its awkward handle, that time and custom may overcome.”

Infantry and cavalry officers were also skeptical when it came to bolt-action rifles. These army officers appear to have equated rapid-fire weapons with the wasting of ammunition. The fear of poorly disciplined troops rapidly empting cartridge boxes and not hitting anything seemingly obsessed combat leaders. Firepower was thought of as being at the expense of the well-aimed single shot. The anti-firepower mindset did have its few situational exceptions. For example, should one be in the process of being overrun by hostile Indians, shooting fast and furious would be the order of the day. However, excepting in extremis, the well-aimed single shot remained the doctrinal solution.

Testing Bolt-Action Rifle Technology

Despite the conservatism within the officer corps, institutional vehicles for technological change did exist and function. The rifle board was such a vehicle, and its members attempted to identify and select the most practical, if not most effective, small arms for army-wide usage. Oversight of rifle boards, as well as the appointment of its members, was the responsibly of the Chief of Ordnance. The boards made their assessments on evidence gathered from rigorous testing and two types of tests were generally employed. Firstly, there were the technical tests conducted by Ordnance personnel at Springfield Armory. These focused upon weapon performance in a controlled environment and entailed tests measuring accuracy, endurance, performance under stress (for example, when the rifle was deliberately fouled with sand or dust), etc. Secondly, there were “soldier” field tests. These tests focused upon the durability and reliability of the weapon when in the hands of soldiers under actual field conditions (typically on the Western Frontier).

Testing “The Ward-Burton Rifle”

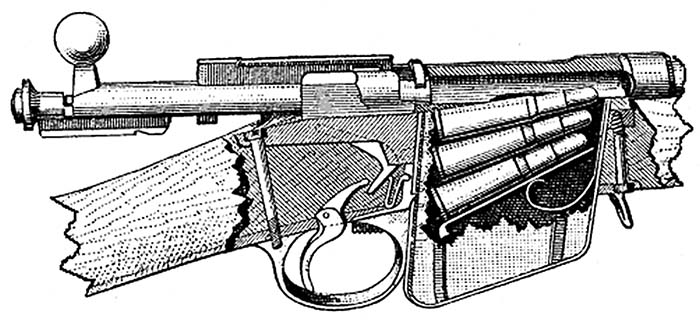

One promising candidate service rifle tested in the late 1860s was the .50-caliber center-fire single-shot Ward-Burton bolt-action rifle. It has the distinction of being the first bolt-action rifle made at the Springfield Armory. The weapon was designed and developed by Bethel Burton and General William G. Ward. An interesting design, the bolt possesses an internal cock-on-closing striker, and is locked by dual-opposing interrupted thread lugs located at the rear of the bolt sleeve. The extractor and ejector are located on a separate bolt head. The safety is located on the right side of the receiver. Albeit the rifle is a single-shot system, a magazine-fed variant of this rifle was made at Springfield Armory. This variant had its magazine housed in the butt stock and held up to eight .45-70 cartridges – a departure from the standard .50-caliber offering. Despite the aforementioned officer “issues” regarding firepower, this combining of the bolt-action and magazine-fed technologies was apparently seen as a practical combination.

In 1870 the Ward-Burton rifle was approved by the Ordnance Department for field trial. However, before the testing began, some 1,015 Ward-Burton rifles as well as 313 carbines were to be manufactured at the Springfield Armory. This delayed the tests for a year. When completed, several regiments were issued the weapons. These were the 1st, 2nd, 5th, 6th, 8th, and 9th cavalries stationed in Arizona, Nebraska, Kansas, New Mexico, and Texas. Officers and the troops had mixed impressions regarding the weapon. Captain Snyder, 3rd Infantry, stationed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, was quoted as: “Thinking the world of it.” However, others thought differently. Central to soldier dissatisfaction was the rifle’s tendency to break as a function of hard usage. Additionally, the absence of a visible side-hammer or cocking indicator made officers worry about weapon safety. A rifle cocked and ready to fire (in the hands of an unknowing or ill-trained soldier) equated to an accident waiting to happen. One captain wrote at the time: “…in consequence of the number of accidents occurring using the Ward-Burton gun, the men of my company are afraid to use them …I would prefer the (Trapdoor) Springfield to the other (test) arms.” Given the unfavorable commentary, the Ward-Burton was soon rejected by the Ordnance Department.

One of the more ambitious rifle boards met from 1872 through 1873. Its presiding officer was General Alfred H. Terry. Terry’s extensive combat record as well as substantial knowledge of small arms made him an excellent choice. His board was involved in the testing of one hundred and eight candidate rifles and carbines. Among those were a dozen bolt-action designs. Terry’s board met in New York City. Despite its urban setting, the bulk of testing was conducted in the West by troops.

An old axiom has it that soldiers tend to favor the type of rifle that they have trained with and fought with – given that the weapon performs well in combat. This behavior seemingly held true in the late 19th century army as soldiers repeatedly favored the Trapdoor rifle over its competitors. And so it was when in March 1873 all the field tests were completed and the results tabulated. Terry’s board declared the Model 1870 Springfield Trapdoor rifle as once again the winner. Chief of Ordnance Benet approved the board’s findings. Duly impressed with their efforts, he added a note of thanks to the board officers for their quality work.

Some political leaders did not share Benet’s enthusiasm for the Terry Board and its process. Congressmen argued that too much money had been spent on rifle testing. Resultantly, they enacted section 1672 of the “law of June 6, 1872.” that curtailed the manufacture of non-service rifles for future tests. In the private sector there were others who also disliked Terry’s work. As a result, Ward & Burton Company representatives wrote the Secretary of War William Belknap in 1873 and asked about the government’s intensions regarding their rifle in light of the Terry board findings. Secretary Belknap responded that the Congressional act precluded any Ward additional Ward-Burton rifles being manufactured at government expense. This cryptic answer apparently ended the possibility of a Ward-Burton service rifle.

More Testing

In the late 1870s a rifle board was once again convened. Earlier boards had mainly tested single-shot rifles, but now a variety of magazine-fed rifles were to be tested, several of which were bolt-actions. Another watershed occurrence was that the major manufacturers were players in the bolt-action category. They included: the Burgess, Winchester-Hotchkiss, Remington-Keene, Colt-Franklin, and Sharps-Vetterli, each of which represented much technological talent. In April 1879, $20,000 was earmarked for the testing of magazine rifles for field trials.

This magazine rifle board soon developed a liking for the Hotchkiss rifle. This rifle represented the combined efforts of Benjamin Hotchkiss and Winchester Repeating Arms Company. Once again, the National Armory at Springfield was central to the effort. Approximately 1,100 Hotchkiss rifles and carbines were manufactured at the Springfield Armory for field-testing. Of these weapons the Ordnance Department issued 202 rifles to the Infantry and 201 carbines to the Cavalry in early 1879. Recipients included the Tenth Cavalry, and Eighth Cavalry, both located in Texas. In 1881, another 490 Hotchkiss carbines were issued to Cavalry troopers. The accuracy of the Hotchkiss rifle was reputedly excellent and matched that of other quality rifles of the era. A good rifleman could reliably place ten rounds into an 8-inch circle at 200 yards, and it had a maximum range of about 500 yards.

A unique design, the Model 1878 Hotchkiss rifle possessed a three-piece bolt, consisting of head, body, and cocking piece. There was only one locking surface. The rear face of an integral guide rib located on the bolt body rested against a shoulder on the right side of the receiver. With a tubular magazine located within the butt-stock, the rifle was loaded with the bolt open. Each cartridge was inserted by way of the open action and then pushed downward into the magazine. The caliber of the rifle was .45-70. The magazine held five cartridges, a sixth could be placed in the chamber, and the functioning of the rifle was cocked by raising the bolt handle to unlock the action thereby pressing the striker back. However, the striker spring was not fully compressed until the shooter pushed the bolt down into the locked position. The manufacture of the rifle also entailed an unusual division of labor. The government made the 513 Hotchkiss rifle stocks, barrels and ancillary hardware at Springfield Armory. However, the rifle actions and butt plates were supplied by Winchester Repeating Arms Company.

By 1882 some of the field tests results were in and once again the Board favored the Hotchkiss. However, there were concerns about the issue of safety. The tubular magazine had the cartridges laying head to toe. This arrangement placed the bullet nose resting up against the primer of another bullet. Fears were that the impact of one against the other might set off the entire magazine. Despite this troubling prospect, tests affirmed its safety. Lieutenant Colonel J.G. Benton, president of the Board, wrote that the “Hotchkiss gun, No. 19, has passed these tests (accident magazine explosion) and from its combination of strength, simplicity, and great effectiveness as a single loader the Board is of the opinion that the Hotchkiss, No. 19, is suitable for the military service, and does, therefore, recommend it as such.” In keeping with Ordnance officer concerns about ammunition wastage by troops, the rifle possessed a magazine cut off that could be activated by a stop placed in the right side of the rifle. This feature enabled the rifle to be fired in a single-shot mode. Perhaps because of the lingering concerns over the tubular magazine, a prototype detachable magazine was developed for the rifle. It held four cartridges and fit in the rifle butt stock. This device anticipated future standardized features of the bolt-action rifle. This magazine was the invention of an army lieutenant named Russell.

The Hotchkiss rifle had two significant competitors in its candidacy for the service rifle title: the Lee rifle and the Chaffee-Reece rifle. On September 29, 1882, Colonel John Brooke, then President of the Board on Magazine Guns wrote to Commanding General of the Army William Tecumseh Sherman (1869-1883) and recommended that Hotchkiss, Lee, and Chaffee-Reece rifles be manufactured on a limited basis for field tests. Over time the Lee rifle apparently gained adherents. The Board indicated that the Lee rifle was deserving of first consideration despite the other two rifles having performed nearly as well in preliminary tests. Benet was supportive and recommended that $50,000 be made available for the production of the test rifles. The plan was to have 750 Lee and Hotchkiss rifles procured by contract and 750 Chaffee-Reece rifles to be made at Springfield Armory. Remington would make the Lee rifle at a unit cost of $16.66, Colt Arms Company offered to make the Chaffee-Reece rifle at the then extravagant unit cost of $150, for a run of 200 rifles. Not surprisingly, Benet quickly dismissed Colt’s offer. Rather, he opted to have the rifles manufactured at Springfield Armory at a unit cost of $35.

Although the army ultimately rejected the bolt-action rifle in the late 1870s, other government departments did not. The Department of the Interior issued Remington-Keene rifles to the Indian reservation police. Additionally, the Navy contracted for 300 of the rifles for trial in 1880. The Remington Keene rifle was a bolt-action small arm patented in 1874 by James W. Keene and manufactured by Remington in 1880. It featured a tubular magazine under the barrel. The magazine contained a long spring that pushed the cartridges back towards the breech, the cartridge then fired and the bolt was cycled thereby feeding another cartridge for firing. Additionally, it had an exposed hammer on the rear of the bolt – the hammer required manual cocking before firing. A curious aspect of this system was that it could be loaded with the bolt open or from the underside with the bolt closed. The relatively high cost of manufacture at $35 per rifle as well as it not being easily adapted to smokeless powder likely had much to do with the manufacture of only 5,000 rifles. Production ended in 1885.

The Lee Rifle

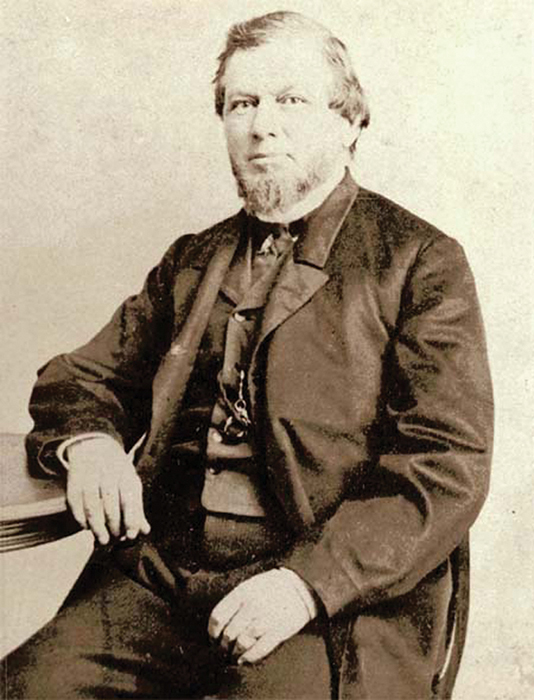

The Lee rifle was another bolt-action rifle that had received serious consideration by the Ordnance Department. It was the invention of James Paris Lee, an émigré from Scotland to the United States. Oddly enough Lee had earlier been a government employee and worked at the Springfield Armory in 1879 when he patented his new magazine-fed rifle. However, he soon departed to seek his fortune elsewhere as an entrepreneur. Lee’s rifle was a modification of his Model 1879 rifle. To begin with, the Model had two follower grooves on each side of the magazine, and the bolt guide rib locked forward of the receiver bridge with an opposite second bolt-sleeve locking lug, as is the case on all later British Lee-Enfields. The structural strength of Lee’s approach anticipated the coming of high velocity ammunition. Most competitor bolt-action rifles possessed only one locking surface. The Lee rifles tested were in the government .45-70 caliber.

Perhaps the most significant innovation found on the Lee rifle is its box magazine (an invention generally attributed to him). Firstly, it was easy to make and of inexpensive sheet-steel construction. Secondly, a soldier might preload a magazine and thereby quickly inserted so as to supply rapid and sustained fire. Thirdly, the magazine held five cartridges in staggered position thus optimizing space within the magazine. Lastly, and probably as a stop to the anti-firepower outlook of Ordnance officers, the rifle could be used as a single-loader. In any case, it had demonstrated its ability to be fired up to thirty times in one minute.

In the beginning, the Lee was withdrawn from testing because of an error on the dimensional drawings submitted by Lee to the Ordnance Department. The error resulted in some confusion regarding the chambering and during early tests it resulted in a bolt lug failure. The ultimate rejection of the Lee rifle afforded it the rather odd distinction of becoming the most successful rifle never to be adopted by the U.S. Army. The rifle’s success in the British military is beyond the scope of this article.

The Chaffee-Reese Rifle

The Chaffee-Reese rifle was another one of the candidate bolt-action rifles that found favor with the Ordnance Department. The invention of Reuben Chaffee and General James Reece of Springfield, Illinois, some 753 of these rifles were produced for test purposes. The five-round magazine was a tubular magazine located in the rifle’s butt stock. The magazine was loaded through a trap door located in the butt plate. As the bolt was cycled, one cartridge were fed forward by means of ratchet teeth – one advanced each cartridge as the bolt was cycled and another kept the cartridges from sliding backwards down the magazine. As one cartridge was pushed into the chamber another was pulled forward to take its place. This rifle could also be fired as a single-loader and as such possessed a magazine cut-off. Though the Chaffee-Reece rifle seemingly was a serious candidate for the service rifle, much of its support may have come from General Reese’s influence with the Ordnance Department. Additionally, the promise of Colt’s interest in the rifle may have added to its luster. No matter, Colt abandoned the project sometime before 1884.

The Brooke Rifle Board

The Brooke Rifle Board tested the aforementioned Lee, Chaffee-Reece, and Hotchkiss rifles. The Trapdoor being used as the standard against which those rifles were measured. Over 149 infantry companies participated in these expansive tests. The Trapdoor rifle was seemingly given an advantage from the onset as all the test rifles were first assessed by troops for their utility as “single-loaders” – a category in which soldier familiarity with the service rifle would be telling. Next, the test rifles were examined in an open ended “all uses” category. Lastly, the three magazine-fed test rifles were contrasted in a side-by-side comparison. In the first category the order of ranking (the higher the score the better) was: Trapdoor rifle, 21, Lee, 5, Hotchkiss, 1, and Chaffee-Reece, 0. In the “all uses” category, the ranking was: Springfield, 46, Lee, 10, Hotchkiss, 4, Chaffee-Reece, 3. Lastly, when the three magazine-fed rifles were compared the ranking was: Lee, 55, Hotchkiss, 26, and Chaffee-Reece, 14. The winner in all categories, once again, was the venerable Trapdoor rifle.

According to reports from the field, the bolt-action rifle was apparently not well liked by the servicemen. Cavalry troopers wrote that the bolt-action rifle was, “Unfitted for cavalry service; too easily fouled with dust…[a] complicated mechanism liable to accident in field service.” They added: “Reloaded ammunition works badly.” (Noteworthy as soldiers were often engaged in reloading spent cartridge cases in garrison.) Such negative commentary from the field served to confirm Ordnance officer skepticism towards the bolt-action rifle. However, the sampling of soldier opinion was not as large as it might have been. Troopers from Companies A and F of the Fourth Cavalry did not respond in time for their comments to be tabulated. This tardiness resulted in a loss of important data since at the time they were hotly engaged in combat with hostile Apaches.

Not surprisingly, the board’s findings provided little reason for transitioning from the reliable and respected Trapdoor rifle to either the bolt-action rifle or lever-action rifle – the latter were also involved in the tests and found wanting. General Benet stated that: “neither of the magazine guns tested should be adopted and substituted for the Springfield (Trapdoor) rifle as the arm for the service.” He qualified his assertion by adding that while he was an advocate for magazine-fed rifles, he nevertheless felt that the Trapdoor rifle was adequate for service use. He recommended that the adoption of a magazine should be postponed until such technologies reached a more mature level of development. This essentially decided the matter. His comments were passed on to the War Department on December 15, 1885.

Officers interpreted the results of all the testing as inconclusive. Time would alter opinions. Moreover, the testing pointed the way to the future service rifle. For despite the parsimonious military budgets and the officer fixation with “ammunition wastage,” the combat practicality of the bolt-action magazine-fed rifle could not be forever denied.

Postscript

On December 16, 1890 the Ordnance Department convened yet another rifle board and on July 1, 1892 its findings were issued. This time the Trapdoor rifle would be replaced with a bolt-action weapon. The reason for this watershed change was other than what might be expected. Two French technological innovations were likely the real agent of change. The first occurred in 1886 when the small-caliber high-velocity bullet (with a 2,000 fps muzzle velocity) was developed for the French Lebel service rifle. The second innovation was that of “smokeless powder.” Such changes nearly ensured the military success of the bolt-action rifle. That is, small caliber bullets traveling at high velocities created enormous pressures in the rifle’s breech. Such breech pressures necessitated the sort of receiver strength that the bolt-action system afforded. Small bullets offered a marked improvement over the large slow-moving .45-70 bullet, especially in terms of hit probability (due to a flatter trajectory and a faster time of flight).

Diehard Ordnance officers tried to adapt the Trapdoor rifle to the new realities. They built a .30 caliber prototype only to discover its architecture was simply not strong enough as the breech block angle made the rifle susceptible to bursting when fired. The Trapdoor legacy rifle had been modified to its limit. On September 15, 1892 the army adopted the bolt-action Krag-Jorgensen rifle. The long deferred decision had finally come to pass.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V17N3 (September 2013) |