By Frank Iannamico

The title of this article is probably confusing to many readers, who may wonder what’s a Model HR4332 submachine gun? Well, it’s better known as an UZI, not made in Israel, but made in the USA.

For any original foreign-made machine gun to be transferable to civilians, they had to be imported before 1968. Very few original Israeli Military Industry factory-made UZI submachine guns were imported before that time, making transferable examples quite rare.

The UZI submachine gun has, arguably, replaced the Thompson as the most recognizable submachine gun on the planet. The UZI was conceived by Israeli military officer Uziel Gal, with a suitable design emerging in 1951. After competing in a rigorous competition against other weapons, the UZI was declared the winner and adopted during 1954, with some recommended changes, by the Israeli Defense Force. The UZI was manufactured in Israel, and under license by FN of Belgium. The 9mm weapon was adopted by over 90 countries. The UZI was even selected by the United States Secret Service to protect the president.

UZI Semi-Automatic Carbines

During 1980, Action Arms of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania began importing semi-automatic only, closed bolt, IMI 9mm UZI carbines. According to the available figures, approximately 72,000 were imported. From 1980 to 1983, the UZI carbines were the Model A version, which had sights that were the same as those on submachine guns. The front sight was used to adjust windage and elevation, the rear sight was a flip L-type with two positions for 100- and 200-meter ranges. During 1983, IMI introduced an updated UZI carbine called the Model B, the primary difference was the sights. The front sight was only adjustable for elevation, the rear sight was also a two-position flip L-type with 100- and 200-meter ranges and adjustable for windage. The Model B also had an improved firing pin safety feature. Approximately 36,000 Model B UZIs were imported. In addition to the 9mm models, there were .45 ACP and .41 AE calibers available. The serial numbers all had an SA (semi-automatic) prefix. Besides being semi-automatic, the UZI carbines had a rather hideous looking 16.1-inch long barrel to comply with U.S. federal laws. While the UZI submachine guns came with a 10.2-inch-long barrel. Action Arms also imported Mini and Micro variations of the UZI. During July of 1989, the UZI carbine was one of forty-three semi-automatic firearms named to be banned from importation to the U.S.

UZI Carbine Conversions

Since the semi-automatic UZI carbines were imported prior to the May 1986 cutoff date to register transferable machine guns, it didn’t take long for many Class II manufacturers and individuals to register and convert many of the semi-autos into machine guns. One question that comes up fairly often on the Class III discussion boards is, “who did factory-correct UZI conversions?” The short answer is no one, because there were few original Israeli UZI parts available when legal conversions were performed, and those parts that were available were very expensive. During the 1980s, UZI parts kits, common today, were not available back then. The UZI was in service with the Israeli military until a phase-out of the weapon began in 2003. Consequently, many semi-auto parts, like the barrels, grip assemblies, and top covers had to be altered and used. The average retail cost of a converted UZI with a registered receiver prior to 1986 was $700 to $750. When you figure in the dealer cost of $479 for the host semi-automatic carbine, there wasn’t a whole lot of profit to be made for the work involved. Several different methods were used for conversions, as well. There were those that modified and registered the receiver, while others registered the bolts, or in a few cases, the sears.

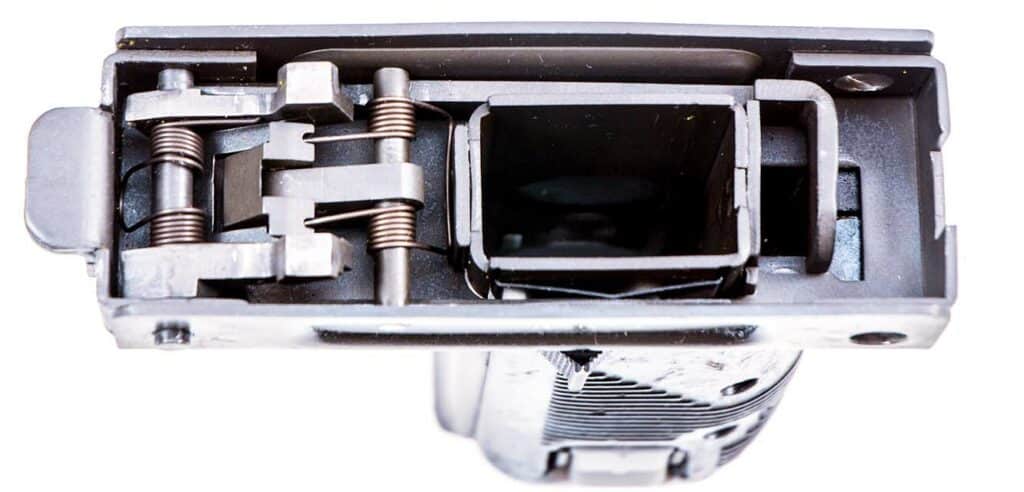

Before the semi-automatic UZI carbines could be imported, there were several design modifications required by ATF so they could not be “readily converted” into machine guns. There were provisions made so that submachine gun parts could not be installed into the receivers. One was a blocking bar that was welded on the inside wall of the receiver, which prevented the installation of a submachine gun bolt assembly, the semi-auto bolt was slotted to clear it.

Another was the trunnion and ring around the feed ramp that prevented the installation of a submachine gun barrel and bolt. To prevent installing a submachine gun grip assembly on a semi-automatic carbine, the submachine gun take-down pins were 8mm in diameter, the semi-automatic carbines used a larger 9mm pin. To prevent the installation of a submachine gun sear, the holes in the floor of the receiver were made smaller.

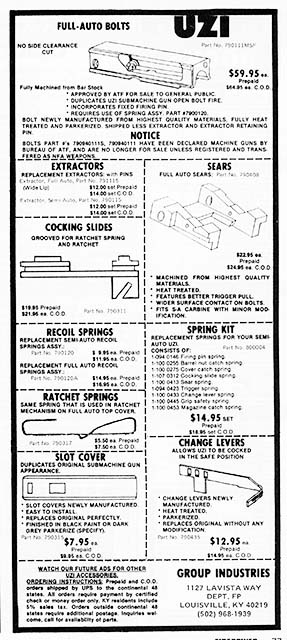

Group Industries

Group Industries of Louisville, Kentucky was founded by Michael Brown during the early 1980s. In the beginning, Brown was basically doing gunsmithing work, concentrating on, then legal, conversions of semi-automatic firearms to select-fire. One of his specialties was converting the UZI carbines into submachine guns. As mentioned earlier, during this period there were very few surplus UZI parts kits available. To support the large number of Action Arms / IMI semi-automatic UZI carbines being converted by himself and a host of other Class II manufacturers and individuals, Group Industries manufactured conversion parts, to include subgun bolts, barrels, top covers, sears, spring kits and more. If you have a converted IMI semi-automatic carbine there is a good chance it was upgraded to a submachine gun with parts from Group Industries.

Group Industries Model HR4332

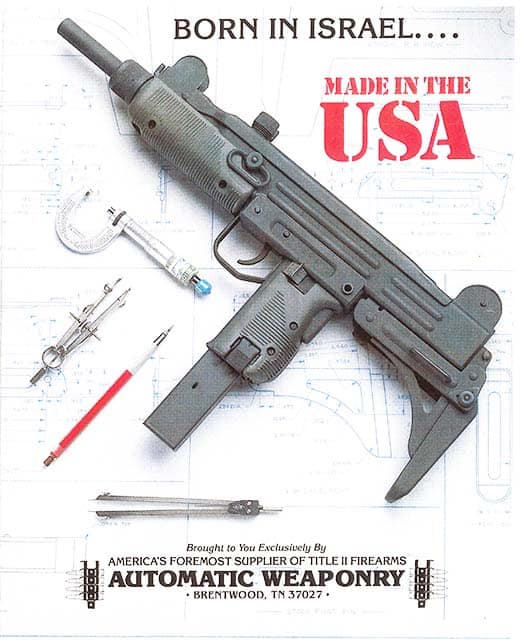

Since Group Industries already had many UZI parts available, it was only natural that they should make their own receivers. To help fund the ambitious project, Brown partnered with Roger Small, president of the Automatic Weaponry Company, located in Brentwood, Tennessee. Part of the deal was that Automatic Weaponry would get exclusive marketing rights to the U.S.-made UZI.

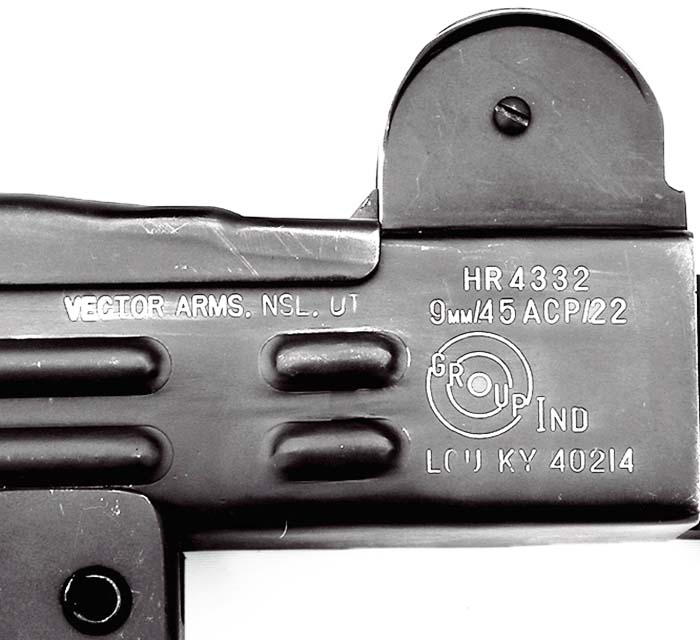

Group receivers, unlike the semi-autos from IMI, were made to submachine gun specs permitting the use and interchangeability of parts with their Israeli made UZI subgun counterparts. By January of 1986, Group Industries had all the tooling and stamping dies needed and was set up to manufacture their UZI receivers, their timing couldn’t have been worse. By the time they got under way everyone became aware of the pending laws that would end the manufacturing and converting of transferable machine guns. Group Industries, like all other Class II manufacturers around the country, worked day and night to get as many receivers registered as possible. No one at the time knew what ATF would be considering complete enough to be accepted and registered. In the end, Group was able to register 4,079 UZI transferable receivers, 109 additional receivers were not accepted and became post-’86 dealer samples. The receivers were stamped from commercial-grade, cold-rolled steel, while the bolt, disconnector, sear and pins were made from 4140 steel. Many parts, including the receivers, were heat-treated. The UZIs were finished in a gray Parkerizing, the plastic furniture was available in standard green or optional black colors. Receivers were marked with three calibers: 9mm/45 ACP and 22. However, ATF is currently rejecting any transfer forms stating multiple calibers. So, if you are transferring an UZI, putting one caliber in the appropriate block will save you some aggravation.

Group Industries manufactured other NFA firearms, but in much smaller lots than the UZIs. Group is known for their BAR receivers, their stainless-steel M16 receivers, M2 Browning and M37 machinegun sideplates. Group also manufactured and registered UZI bolts.

HR 4332 The McClure-Volkmer Firearm Owners Protection Act

On April 10, 1986, U.S. Representative William Hughes, a Democrat from New Jersey, attached his House amendment 777 to H.R. 4332 “The Firearm Owners’ Protection Act”. The amendment made it “unlawful for any person to transfer or possess a machinegun except in the case of a machinegun that was lawfully possessed before the date of enactment.” The added amendment was passed by a voice vote. On 19 May 1986, then President Ronald Regan signed the bill to become Public Law 99-308. As a bit of sarcasm Group Industries named their new UZI submachine gun the Model HR4332 after the House of Representatives Bill.

Soon Group Industries would experience more problems, jeopardizing the future of their UZI submachine gun production. Group’s partners, Brown and Small, got into a legal dispute. By this point only 761 HR4332 submachine guns had been completed by Group. During 1993, Group Industries filed Chapter 11 bankruptcy for protection from creditors. But by 1995 the court ordered the assets of Group Industries to be liquidated under Chapter 7. An auction was held on 24 August 1995. A successful bidder was Marcos Garcia who bid $265,000 for 3318 transferable UZI and 109 post-May dealer sample UZI receivers. With the buyer’s premium the total bill was $291,500, resulting in each receiver costing $85.06. The winning bidder was the representative of Ralph Merrill, president of Vector Arms, they did not bid on any of the parts or fixtures to complete the guns.

There were many other firearms, parts and vehicles sold at the auction. One related lot of 15,505 Group Industries’ semi-auto UZI receivers sold for $550 or about four cents each. The reason for the low bid was the receivers were deemed post-1994 manufacture by ATF and at that time could not legally be made into UZI carbines. However, after the assault weapon ban expired in 2004, many of the receivers were assembled into semi-automatic carbines by a number of companies.

Vector Arms

It seemed as though Vector would pick up where Group Industries left off and resume the manufacture of a U.S. made UZI, but it would take years and a lot of effort to finally get the guns built and marketed.

After Vector Arms won the transferable UZI receivers at the Group Industries auction, the company began to look for a source for the parts needed to complete the guns. Logically, the first places to look for parts was from the companies that made them, but the UZI was long out of production by IMI and FN, and neither company was interested in a parts run. There were a few other countries that manufactured copies of the UZI, Croatia and South Africa. A deal with Croatia fell through, but South Africa had brand new UZI submachine guns stored in a warehouse they wanted to sell. However, getting the guns disassembled and the needed parts shipped to the U.S. proved to be a logistical nightmare. Due diligence paid off and the needed parts made it to Vector’s facility in North Salt Lake, Utah and production began in 1998. Finally, in May of 1999 nearly four years after procuring the receivers from the auction, the first Vector UZI submachine gun was shipped. The retail price was $2995 and the gun came with a one-year factory warranty. Today, a transferable UZI costs up to six times that amount. The new UZI was an immediate success. Thirteen years after the 1986 ban on machine gun production, brand-new submachine guns were again available. The number of submachine guns Vector had to sell was very limited and were soon sold out. To remain in business, Vector obtained a number of the Group Industries semi-automatic receivers and began to build UZI carbines, which at this point in time, 2004, were again legal to manufacture.

Although Vector UZIs will have Group Industries name and logo on them, Vector assembled guns were marked on the left side of the receiver “Vector Arms NSL UT”.

| This article first appeared in Small Arms Review V26N3 (March 2022) |